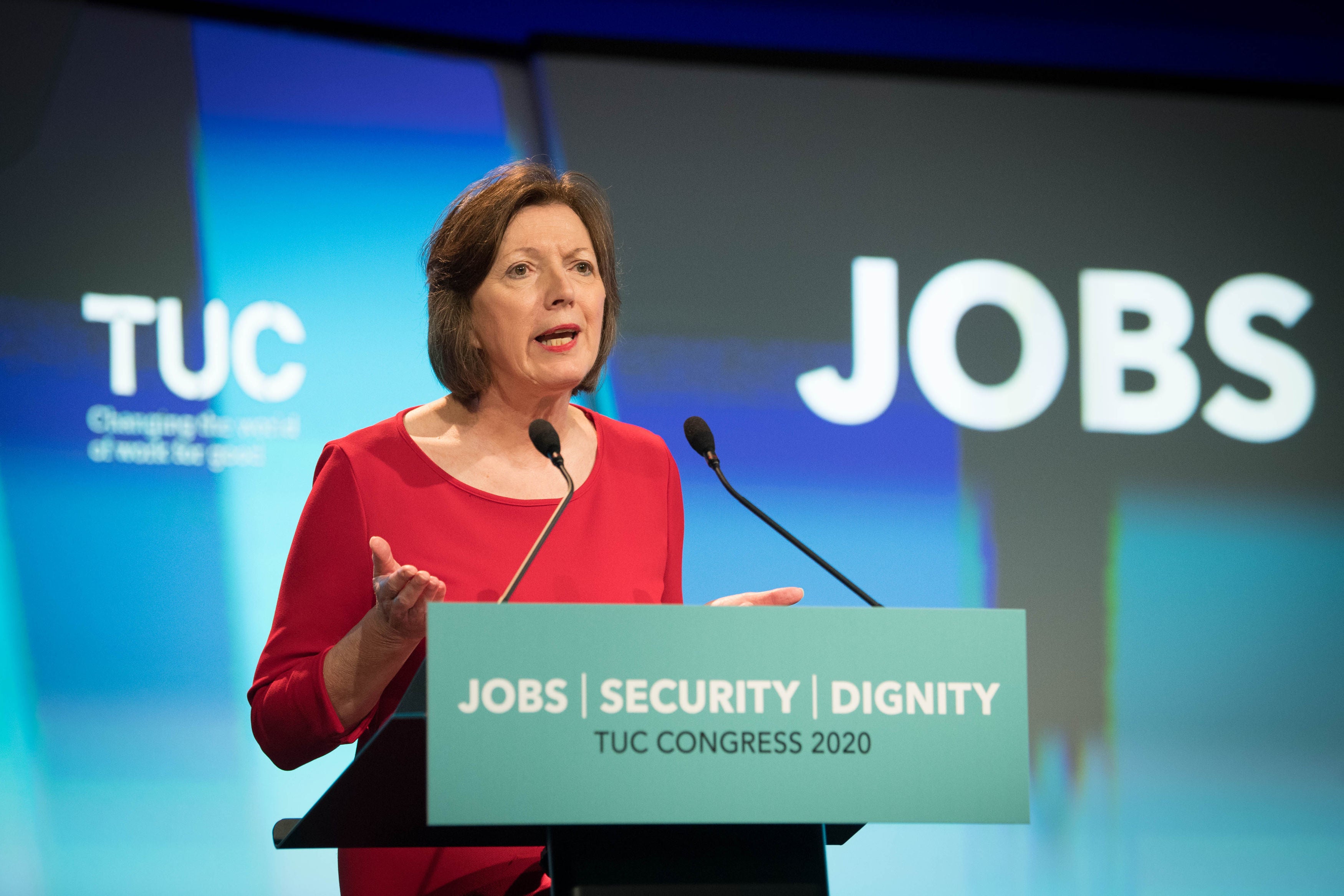

‘The whole system needs fixing’: Frances O’Grady on the UK’s recovery from coronavirus

The general secretary of the TUC tells James Moore what we need to get the UK economy moving again, and laments the lack of green initiatives that could have delivered much-needed jobs

Frances O’Grady lives her life at high speed. Even a global pandemic hasn’t been able to slow the TUC general secretary down. But while she has adapted to working remotely, like millions of other British workers, the transition hasn’t been easy for her because of who she is.

“I think you know me well enough to know that I’m a social creature, so this is torture in some ways. I really miss people,” she tells me. Inevitably, we’re connecting using technology, in this case Microsoft Teams. Its software O’Grady uses regularly but she admits there’s been the occasional banana skin.

“I didn’t realise everyone was listening on a teams session when I confessed to a colleague that while it’s lovely not to have to commute and to be able to stick my washing up at lunchtime, I miss having a chat and putting the world to rights.”

O’Grady is not without company at home. She has her two grown-up children with her but it isn’t the same as the constant flow of interactions she would be enjoying in more normal working conditions.

One of those interactions has proved particularly important: we’re speaking ahead of this week’s anniversary of the furlough scheme, the Job Retention Scheme to give it its full title. O’Grady played an important role in its creation at the start of the pandemic when unions and employers were called into Number 11 Downing Street during the early days of the Covid-19 crisis.

It has proven to be one of the government’s most successful pandemic policies, something a defence lawyer might put up in mitigation against its many other failings.

At 5.1 per cent and rising, unemployment is at a five-year high. Without the scheme that figure would be very much worse. “It supported as many as 9m people at its height, and 4m even now,” O’Grady points out.

You’d think, given the scheme’s success, and the constructive role she played, that O’Grady would have been at the front of the queue when the membership of the government’s Build Back Better council was decided upon. It didn’t happen.

So while O’Grady makes clear she stands willing to work constructively with “anyone” – she's campaigning hard from the outside to get it extended. “When the Chancellor brought it in, I think he made the right call. What I don’t think is the right call now is to announce an arbitrary date to end it.

“Look, I’m not a public health expert. Nor are any of the government’s ministers. So, given where we are now, I think they should say we’re going to keep it in place. I think they should say that we are going to keep it for as long as we need it. It is a success story. A lot of firms have been able to get back on their feet because of it. It’s time to give people a break.

With sick pay so low and with 2 million people not qualifying, sending people messages to self-isolate was never going to work

“Most people are sensible. They want to get back on their feet. Most firms want to get back on their feet too. They want to be working. But it all depends on the pandemic and the reopening timetable and that’s been built on hope as much as anything else.

“There may be new variants out there. If they said keep the furlough for as long as it’s needed it would give people confidence.”

It’s not just the furlough O’Grady is concerned about. We’re speaking on the day the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee warned that the government’s £37bn Test & Trace scheme risked treating the taxpayer “like an ATM machine” and criticised it for having “no clear impact”. O’Grady uses this to make a point about Britain’s miserly – and much criticised – statutory sick pay of £95 a week.

“With sick pay so low and with 2 million people not qualifying, sending people messages to self-isolate was never going to work. This is another cause of high blood pressure to me because it’s just so obvious to anyone with a brain. You need to ensure sick pay is universal and because that hasn’t been done, it is placing people in the position of either doing the right thing by their community or doing the right thing by their family. No one should ever be placed in that position.”

When I suggest that the idea of a £500 self-isolation payment – floated by Health Secretary Matt Hancock before being swiftly squashed by the Treasury – had potential, O’Grady demurs.

“That would just be playing catch up in a crisis and we shouldn’t be doing that. The whole system needs fixing. It’s fallen way behind other countries. They’re trying to avoid what’s staring them in the face.

“I wouldn’t expect ministers to take what might amount to an 80 per cent cut in pay to self-isolate so they can’t expect other people to do that either.”

She also compares the struggles of the Test & Trace system with the vaccination programme, an effort that hasn’t involved private contractors. It has been delivered by the public sector in the form of the NHS and its personnel. “I really do think it’s a case of compare and contrast. When I went down to get the jab it was brilliant; friendly, humane, efficient. It was fantastic. I think we’re all starting to learn what’s valuable and what matters in life. The good old NHS, eh.”

A conversation with Frances O’Grady, while never anything less than entertaining, usually involves something of a rollercoaster ride. One minute she’s laughing, indulging in her trademark self-deprecating humour, and turning on the charm, of which she has considerable reserves, up to the max. The next she’s breathing fire, such as when she brings up the 1 per cent rise proposed for NHS staff.

“A profound insult,” is how she describes it, while also calling for other key pandemic workers to be recognised for the contribution they have made. She’s also underwhelmed by the budget, contrasting it with Joe Biden’s ambitious $1.9tn stimulus plan – “we need a Biden boost” – and lamenting the lack of green initiatives, particularly those that could have delivered the jobs Britain is going to need.

“It’s not just that the budget was unambitious. So much was hidden in the small print, including more cuts to public services and it wasn’t long before the chancellor got headlines he didn’t want around nurses pay.

“Take green issues. We set out an £85bn plan for a million green jobs over two years, in technology, transport, infrastructure. We wanted to do the hard work to set out a plan. This budget is not even close. Direct spending for green initiatives amounts to just £99m nationwide in England and the cuts to green-home grants takes out £1.25bn net. All this while we’re trying to stake out a leadership position ahead of Cop26.”

We have 1 million people on zero hours contracts and 2 million who don’t qualify for sick pay. Working mums have had no choice but to cut hours

Cop26 is the United Nations Climate Change Conference, which kicks off in Glasgow on 1 November. The UK, as host, has already come under fire over controversial plans to allow a new coal mine to be built in Cumbria. While the local council, which is reconsidering the plans, may yet bail the government out of that embarrassment, the budget will remain there in black and white.

O’Grady is also gravely concerned about the people who are getting hit in the latest wave of redundancies. It’s hitting British workers even with the furlough still in place.

“If you leave the free market to its own devices you know you get roughed up. All the evidence is that it is young people, disabled people, working mums. They’re all treated as disposable labour. The government can step up here. The government can say we are going to ensure that doesn’t happen by making sure people have strong rights at work. They can properly enforce them and recognise that the unions have a role to play. But so far it hasn’t happened. The government has been promising forever that we are going to have our rights not only protected but enhanced. Where is that? We have 1 million people on zero hours contracts and 2 million who don’t qualify for sick pay. Working mums have had no choice but to cut hours, nurseries are going down the pan, social care is in crisis. Where is the action to address this?”

O’Grady says she’s disturbed at some of the potential consequences. She describes them in characteristically blunt terms: “When it comes to women, we’ll be back to kitchen-sink territory if we’re not careful. I’m thinking back to how I would have coped when my children were young. I wouldn’t have coped very well. To have kids under your feet. To have to home school.”

She shakes here head before returning to the subject: “It seems obvious that the majority of working people have had a really tough pandemic and the balance isn’t right . We’ve too many workers on insecure contracts and low pay who don’t feel they have a voice. The government needs to wake up and listen. All this does show that there’s never been a better time to join a union and we are seeing membership rising in many sectors.”

Closer to home O’Grady is adapting not just as a worker but as an employer too. While she is someone who comes alive in the workplace when she’s constantly in and out of meetings, there are plenty of others who find working from home suits them better. This is something she recognises.

“We’re going through a consultation at the moment. It’s basically everybody trying to take responsibility for thinking through the pros and cons of how we work individually and as a team. I think we can accommodate people’s needs and preferences and look after the needs of the team and make sure we do a brilliant job. There will be more flexibility, it’s almost certain.”

There will be more flexibility at a lot of workplaces, particularly those that are managed well. It’s one thing that might yet assist some of the groups that are suffering so badly. As a disabled worker, flexibility has kept me in job.

O’Grady is clear: “If you want to manage it well, we can help with the transition. We’re not the enemy here. Our members just want a voice.” Perhaps it’s time to listen to her and given them one.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments