You’ll never walk alone: Can football ever replace religion?

Like religion, football involves ritual and communal participation, holy places, icons, and distinctive garb. But unlike religion, it rarely if ever holds you accountable, writes Eli Gottlieb

My calendar used to be full of recurring appointments that gave order to my week – from staff meetings to parents’ evenings . Some events, like family dinners, occurred with such clockwork regularity that they didn’t even need a calendar entry. In the more distant past, my Orthodox Jewish upbringing punctuated my week with other kinds of fixtures, such as Friday sunsets and Saturday morning synagogue services. But it’s been years since I attended synagogue for anything other than a family bar mitzvah, and my relaxed approach to Sabbath observance has made me less attentive to nightfall.

Today, my calendar is sparsely populated. Since leaving a C-suite job to work as a consultant, I have no staff meetings. Since the kids finished school, I have no parents’ evenings. These days, only one kind of recurring appointment remains: the calendars I import from football websites listing all of Liverpool and England’s fixtures.

It was only while teaching in Washington, DC, however, that I noticed football colonising spaces in my life vacated by religion. I guess it was a desire for company that first drew me to the Queen Vic pub and LFCDC (Liverpool Football Club, DC). But my weekly attendance at live screenings of Liverpool’s Premier League matches with Washingtonian fans soon took on a more ritual aura.

Watching Liverpool games at British pubs overseas had become a habit years earlier. It began about a decade ago in San Diego, when I exchanged the sterility of a conference hotel on a Sunday morning for the smells of cooked breakfast and waves of synchronised oohs and ahs with every near miss and explosions of joy or disappointment with each goal. It was an odd, pleasant feeling; both of being a stranger and still one of the family; an intrepid explorer going off piste but also a lonely business traveller seeking a taste of home in a strange land. It wasn’t Cheers, where everybody knows your name. It was better: somewhere to belong for a couple of hours without anyone giving a damn what you’re called.

Since San Diego, I can’t recall a single overseas trip that didn’t include at least one such dip into the parallel universe of Liverpool supporters’ pubs. I’ve celebrated and mourned with Kopites in Paris and Vienna, and sung boozy renditions of “You’ll Never Walk Alone” in New York and Limassol. But it was only after a few weeks in DC that I realised that the Queen Vic had become my synagogue – my shul.

It had a lot to do with timing. Most premier league matches are played on Saturday afternoons. The lag between Eastern Standard and UK time makes this Saturday morning in Washington. Not perhaps the healthiest time of day for your first beer but perfect for reactivating a former shul-goer’s muscle memory. But there was more to it than timing: The Queen Vic was a strenuous half-hour bike ride from my apartment. It took planning and effort to get there in time to grab a good seat. It took commitment.

When home fans saw the two ecclesiastical supporters in attendance, they thought victory was assured. Arsenal then suffered their worst home defeat in 30 years, losing 2-6

Commitments are hard to come by these days. In the digital age, we’re used to easy entries and exits. At the flick of a thumb we subscribe and unsubscribe, swipe left or right. We’re hungry for novelty and have short attention spans. If we can avoid tying ourselves down – to people, groups or institutions – we do. It’s no accident that church attendance is down and divorce rates are up. These are symptoms of an underlying crisis of commitment that affects different areas of our lives, from the higher frequency with which we change jobs to declining voter turnout.

The crisis is double-edged; it involves not just under-commitment but also over-commitment. Politics are becoming increasingly tribal, public discourse less civil, and religious extremism and xenophobia more widespread. Slavery to unrealistic body images, work schedules, and ideals of parenting, to name just a few contemporary forms of individual over-commitment, has led to increased incidence of eating disorders, anxiety and other health problems.

All of which makes contemporary football fandom so intriguing. It’s a commitment; but a light and easy one. It provides a sense of belonging. But it makes few demands. Like religion, it involves ritual and communal participation, holy places, icons, and distinctive garb. But unlike religion, it rarely if ever holds you accountable. The Queen Vic gave me community with anonymity. It was a shul I could skip with impunity. No one needed me for a minyan (the quorum of 10 people that Jewish law requires for a prayer service).

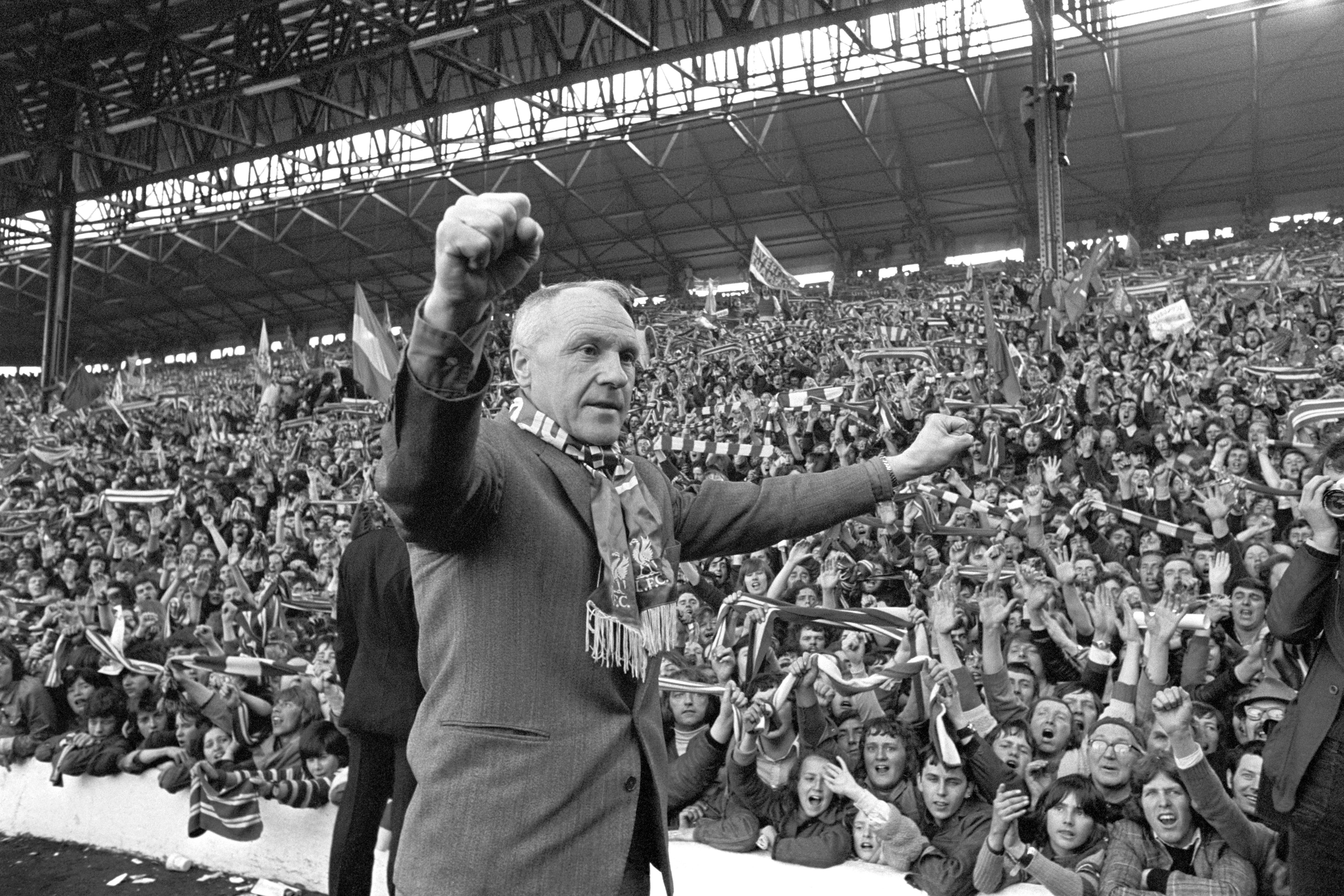

Social scientists and football insiders have often noted the similarities between the devotion of fans and religious believers. As Bill Shankly, Liverpool’s messianic manager of the 1960s-1970s, put it: “It’s more than fanaticism. It’s a religion to them. The thousands who come here, come to worship … [Anfield’s] a sort of shrine, it isn’t a football ground.” On another occasion, he raised the stakes even higher: “Some people believe football is a matter of life and death. I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.”

God is often invoked in football contests, not only in chants from the stands and prayers for success, but also in post-match analysis. Jonathan Sacks, the late British Chief Rabbi, liked to tell of the time he attended a home match with fellow Arsenal fan and then Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey. When home fans saw the two ecclesiastical supporters in attendance, they thought victory was assured. Arsenal then suffered their worst home defeat in 30 years, losing 2-6 to Manchester United. When a journalist reporting on the match suggested this was final proof that God does not exist, Sacks countered: “To the contrary. It proves that God exists. It’s just that he supports Manchester United.”

Some people believe football is a matter of life and death. I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that

Like religion, your football team used to be determined, first and foremost, by family and neighbourhood ties. As mobility increased and televised matches enabled you to follow teams from afar, such ties stretched to include connections of more tenuous kinds. With increasing commercialisation, football’s reach expanded dramatically towards the end of the last century. Its associations with social class also changed, becoming gentrified and middle-class, with the advent of all-seater stadia, rising season ticket prices, and cable and satellite connections that made it possible to follow games from the comfort of your own home.

By the 1980s, when I was growing up in north London, it was no longer assumed that you’d support local teams, Arsenal or Spurs. Football fandom had begun to approximate pop fandom. It was a statement about your taste; an association that burnished your personal brand. That’s how I became a Liverpool supporter.

Around the age of 10 or 11, I could no longer shrug off questions about which team I supported with a non-committal, “I’m not really into football.” It was weird not to support a team; insufficiently masculine. So, I chose the winning team. I was exactly the kind of fairweather fan that is the butt of familiar jokes: How do you confuse a Man Utd fan? Show him a map of Manchester”. And chants: “Where were you when we were shit?”

It was only in my twenties that I started following Liverpool in earnest, by which time they weren’t winning much anymore. I had no dramatic revelation. Fandom crept up on me. I fell into the habit of watching Match of the Day and began to feel I had more at stake in Liverpool’s matches.

This origin story doesn’t follow the standard narrative. You’re supposed to follow a football team for more organic reasons. If it’s not your neighbourhood team, then it’s the team your father or grandfather or cool, older cousin supported. The closest thing to a football fan in my immediate family was my maternal grandfather, a Polish-Jewish refugee who arrived in England on one of the last boats out of Dunkirk in 1940.

He became a Spurs fan, attending many Saturday home matches at Whitehart Lane. But he would never have dreamed of taking me with him. His fandom wasn’t exactly a secret but it was something of which I think he was a little ashamed, or at least about which he wanted to be discreet. Attending matches was a desecration of the Sabbath and, although he was more traditional than Orthodox, he had been raised with a respect for religion that made him reluctant to flout Jewish law publicly. No less significantly, my snobbish Belgian grandmother probably considered his interest in football vulgar, unbefitting a man of the social status to which she aspired.

Such ambivalence was common among north London’s Orthodox Jews in the Eighties. Football fandom was a guilty pleasure. It lived in tension with religious seriousness and social respectability. These tensions stretched to breaking point when Arsenal or Spurs were in the FA Cup. Only the most righteous would wait to find out the result on Saturday night. The less devout would crowd around the local electrical goods store from kickoff to final whistle, watching the match as it played out silently on the banks of TVs displayed in the shop window. More daring fans put their TVs on timer before the Sabbath and invited friends over for a clandestine viewing, curtains drawn to avoid the disapproving gaze of pious neighbours.

Such border skirmishes between football and religion hint at competition. It’s as if the same parts of our brains that govern religious devotion can be stimulated equally or more so by football.

The globalisation of football fandom has made it even more similar to religion. You don’t need to come from Jerusalem, Nazareth or Mecca to be a Jew, Christian or Muslim. And you don’t need to have skin of any particular colour or speak any particular mother tongue. You can walk into any local synagogue, church or mosque, pick up their version of the common book of prayer, and join in. Those supporters’ bars I’ve visited around the world are little different from local places of worship.

As more of our communing migrates online, national and cultural boundaries are fading further into the background. A few years ago, Twitter’s algorithm suggested I follow a feed called LFC Indonesia, a supporters’ group with more than 200,000 followers. That’s a mind-boggling number. They would fill Anfield almost four times over. The group is not just virtual. The feed contains posts of hundreds of red-shirted locals watching matches together on big screens in Jakarta.

Like commitment to a religion, commitment to a football team carries with it an expectation of exclusivity. You can’t support Liverpool and Everton just like you can’t be Jewish and Christian. Well, it’s empirically possible: there are outlying Jews for Jesus and the occasional Merseysider who supports both Red and Blue. But it’s not only statistically rare; it’s also frowned upon. Those inhabiting such margins are suspected by both mainstreams.

In these times of social isolation and growing self-obsession, it’s good to have something that connects me to a larger collective

Even today, when categories like gender, sexuality and nationality are being deconstructed, and fluidity and hybridity of all kinds are celebrated, the categories of religion and football fandom retain this presumption of exclusivity. You can’t be team-fluid or soccer non-binary. In fact, this may be more true today of football even than it is of religion.

Consider conversion. When someone switches religion these days, we’re ready to put the change down to an authentic spiritual search. When fans switch teams, we consider them fickle and flighty. This premise underlies Ali G’s faux-naif question to the late Major General Ken Perkins about whether he considered switching sides when the Germans had the upper hand in the Second World War. In response to Perkins’s incredulity, Ali G presses on with an analogy to his own support of Manchester United the previous year until he realised they wouldn’t win the double, at which point he switched to Arsenal. The joke here is not just the inappropriateness of the analogy. It’s also Ali G’s own shameless disloyalty, which is so at odds with Perkins’s reputation and bearing.

During international competitions, circles of fandom expand, as people who don’t usually follow football get caught up in the excitement of rooting for their national team. Over the past few weeks, this was magnified for England fans, as the national team’s impressive run in Euro 2020 coincided with the easing of Covid restrictions. The hope and excitement were palpable. So too, following England’s eventual defeat by the slimmest of margins, were the disappointment and sense of loss.

I watched the Euro 2020 final in my Israeli living room with a bunch of old friends from England. This was an event too momentous to experience alone. I wanted to be able to look back and remember where and with whom I’d been when we won or lost. We were all gutted by the defeat. But already, looking back, I’m able to focus more on the laughs and nervy excitement we shared during the match’s first half than the silent dread that filled the room as we watched the final penalties.

This is one of football fandom’s great advantages over more demanding kinds of commitment. The highs and lows, the risks, and the sense of jeopardy, are all symbolic. That doesn’t make the disappointment any less real. But it does make it easier to shrug off.

Those England and Liverpool fixtures in my calendar lay down a rhythm of excitement and participation. They provide me with opportunities to commune with others, whether online, in a foreign pub or in my living room.

But they ask nothing of me. I’m no one’s tenth men. My fandom commits me to nothing beyond my own entertainment. In these times of social isolation and growing self-obsession, it’s good to have something that connects me to a larger collective and requires me to involve myself, however loosely, in the trials and challenges of others. But in the absence of demands or accountability, such commitments and forms of belonging can’t provide purpose or direction. For that, only more taxing commitments will do.

Eli Gottlieb is a British-Israeli cultural psychologist and advisor to government and nonprofit organisations on leadership and strategy. His research examines connections between cognition, identity, and culture

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments