My father, my son, and I

As his son leaves the family home for university, David Barnett fondly recalls his late father, and wonders whether he’s done enough to prepare his own child for the world

I never felt my father’s ghost at my shoulder more keenly than on Tuesday. It has been five years since I lost him, which always feels to me an unusual thing to say. As if I had been careless and misplaced him, or let him wander off somewhere. And thinking about it, perhaps I did, in a way.

Journalism, which has been my working life since I was 19 years old, loves an anniversary: a neat one like a decade, or 20 years, or a century. But it is not the five years since my dad’s passing that brings his shadow falling over me; it is instead my own son’s departure for university – almost to the day of my father’s death.

We are a thin, brittle lineage of Y chromosomes, the Barnetts. My son has a sister, as did my dad. I am an only child. My paternal grandad, after whom my son is named, had brothers, I think, but I don’t remember them other than as vague uncle-ish presences in my childhood.

My male bloodline feels just that: a direct linear link, precisely one person wide, stretching back who knows far? I have never felt any kind of urge, primally or purposely, to continue this bloodline; to demand, like a medieval king, a male heir. I might have been gifted purely my daughter, or two daughters, or had no children at all. Ensuring a male heir was never an expectation I felt weighed heavily upon me.

And yet, today, as my son departs for pretty much the furthest possible point to which he can go and still be in mainland England, that procession of men – of whom I have only known my son, my dad and my grandad – seems to be acutely present, at my back and looking forward.

I think it is because, as my son begins a life of study where the sun sets into the Atlantic Ocean, and my dad rests, in the quiet dryness of his box of still-unscattered ashes, within reach of where my mum sleeps fitfully each night, I feel suddenly and somewhat inexplicably alone.

This is curious, because I am anything but alone. I am surrounded by people I love and who love me. I have family, and friends, and even though I spend my days typing alone at a laptop, I feel at the centre of a spiderweb of people, across the media, book publishing, and comic book production.

That final summer he lay in what used to be my old bed, listless, the fire that had always been in his eyes totally doused

The threads of my many and varied connections are constantly vibrating and singing, from early morning until late night. But the unusual sense that overwhelms me right now is not those connections. It’s about the parade of men of which I was at the head until a little over 18 years ago, when my son arrived.

I look back, and that endless column is as faint and insubstantial as smoke; a stream of absences. I look forward, and there is an absence there as well. Too late, I wonder if I ever did the right thing by those who inhabited the spaces directly behind and before me.

I am excited about my son’s new life, and any misgivings I have are purely selfish, concerning the space he leaves behind rather than the ones he will go on to fill. He is likeable, and capable, and affable, and on the brink of adventure. I will miss his presence, despite our occasional petty bickering, which blows itself out in seconds. But he is not gone from everywhere, like my dad is; he is merely gone from here. He is out there, still, in the world.

And what will my son make of the world? More importantly, what will the world make of my son?

I realise even as I type those words that what I really mean is what will he think of it, and what will it think of him? But it occurs to me that the more literal definition is pertinent here. What will it make of him – how will it forge, and shape, and steer him – when I am not there to do that?

And then I think, was I ever? And this, I realise, is what it is all about. Did I do right by my son? Did I do right by my dad? Because now, if I didn’t, it’s too late.

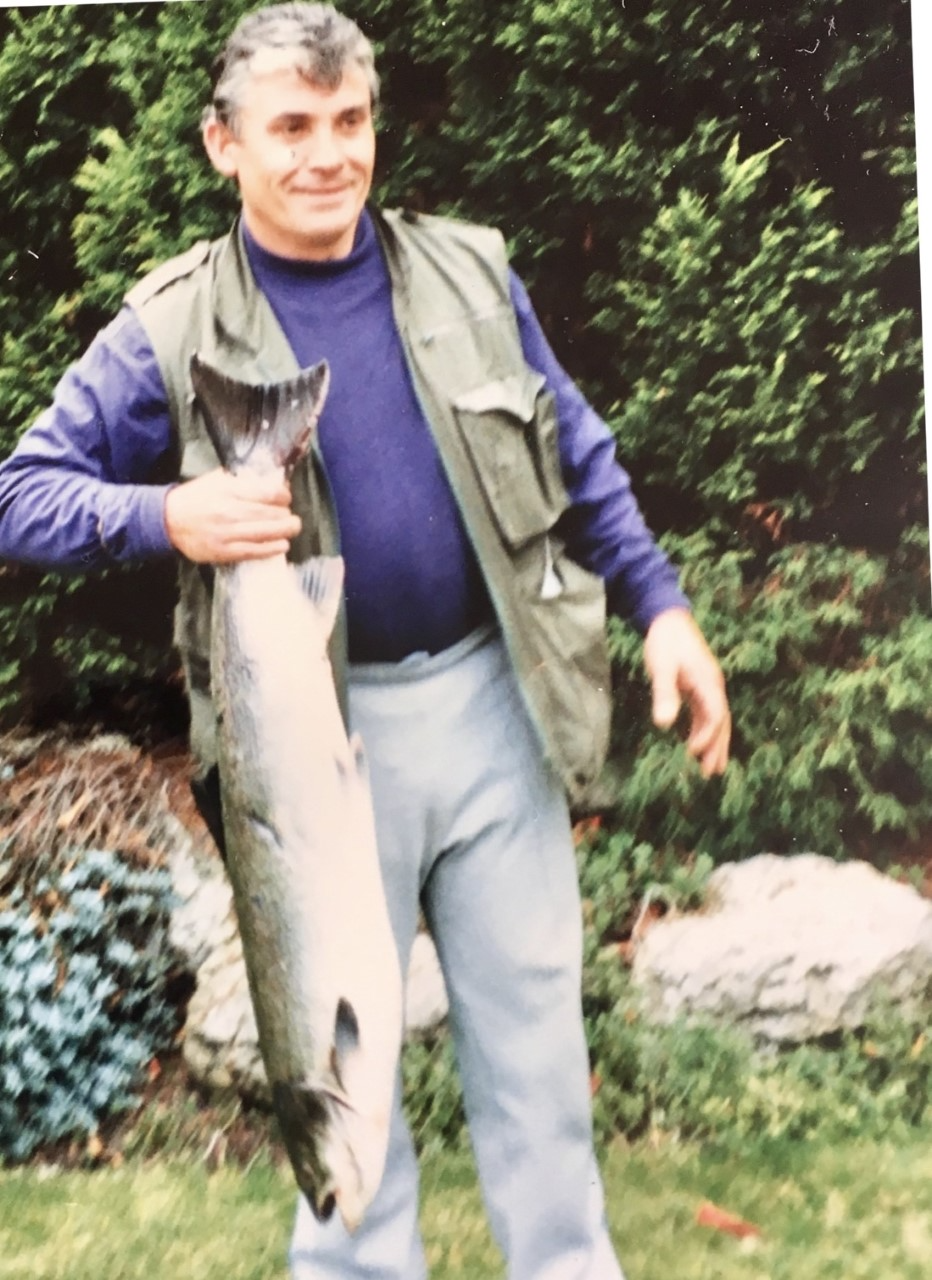

My dad, Malcolm Barnett, died on 21 September 2016, pretty much the last official day of summer that year. He had always loved summer, his skin turning a deep, mahogany brown at the faintest suggestion of sun. He loved our summer holidays, whether they were taken in chalets at Pontins in Pwllheli or in a tiny caravan by a river in the Lake District, or in what we quaintly called “the cottage” – a mid-terraced townhouse, really – in a small town in Dorset. He would take me on spontaneous drives when I was small, to towns on the Lancashire coast or straight up the M6 and into Scotland, declaring that we had travelled a whole 100 miles while I stared, agog, at the thought of such an epic journey. We would go fishing in rivers and canals and ponds, a passion of his which I never quite managed to share, once fleeing along a bank screaming about a snake as he deftly struck with his rod and pulled a sleek eel from the still water.

But that last summer, and the one before, had not been happy ones for my dad. His inventory of illnesses and conditions that he collected over the final years of his life is too long and personal to list here. That final summer he lay in what used to be my old bed, listless, the fire that had always been in his eyes totally doused. He was 71, yet he looked a decade older: thin, and pale, and weak, where he had always been stocky and Technicolor and strong from decades of working outdoors as a builder.

At his funeral I asked people not to remember him as they might have seen him in the last couple of years, shorn of his famous sense of humour and his generosity of spirit, his once seemingly boundless reserves of love and energy depleted as he stared out of the window at nothing in particular.

I said that because, at some point in those final years, I forgot all those things – those days out, and fishing trips, and sitting on his shoulders with my hood pulled tight at a North Wales holiday camp. I forgot them, and slipped into a state of thinking that the now was all, and that now was how things had always been and would always be. My dad was becoming ground down by chronic pain, and against my better judgement I increasingly lost patience with him, becoming exasperated at the things he said or did, allowing my annoyance to rise at trivial things that were of no importance at all.

But things were not always that way. And things would not always be that way. And one bright September morning I got a phone call from my mum to say that he had died in the night.

My son and daughter knew he had been ill. He was no longer quite the same grandad who used to play with them, and take them on day trips, and indulgently allow them to watch endless reruns of Tracy Beaker and Pokemon on the only TV in the house when they stayed for long summer holiday weeks. The morning he died, we packed them off to school without telling them what had happened, and I set off on the hour-and-a-half drive from West Yorkshire to Wigan.

As a young man he had been plucked from his mainly mining community on the edge of Wigan and sent to Burma. He was a Chindit, one of the Forgotten Army fighting the Japanese in the jungles

On the way I stopped, and – I didn’t know why – bought a packet of Marlboro Gold. On the back roads, skirting Bronte country, just before the invisible delineation between my adopted Yorkshire and my native Lancashire, I pulled into a lay-by and smoked four in quick succession, staring out over the hills and moors, not really knowing how I was meant to be feeling, because nothing like this had ever happened before.

I got to my old home, and found a palpable air of shock permeating the living room like an electric field, emanating from mum and my auntie and uncle. “Where have they taken him?” I asked. This was all new to me. I assumed that someone, somewhere, would take control of this situation. That they would come and deal with it all.

“Nowhere,” said my mum. “He’s still upstairs. They haven’t been yet.”

And there he was, on the carpet at the side of the bed he had inhabited for the last year or more. His eyes were open. I put my hand on his bare arm, then his face. I can’t remember whether he was warm or cold. “Stop messing about, Dad,” I said. “Get up.”

He didn’t, so I sat down at the side of him, and wished he was back in his bed, as riven by pain as he had been, and I wished I could take back all the snippy little comments I’d made to him over the past few years. I remembered, suddenly, the windswept holidays in Wales and singing “The Fishermen of England” as we tramped along a towpath looking for a spot to sit on our wicker baskets, and him pressing a note into my hand and telling me to run off and get ice creams for everyone from the shop on Swanage beach, and that if there was any change I could buy myself a comic.

If I had been in any kind of denial about what was going to happen, dad wasn’t. He once said to my mum: “In order to live, you need a good set of lungs and a good heart, and I have neither.” And he was right. It was his heart that did for him in the end, as he tried to get out of bed in the middle of the night. But he was also wrong as well. Because if there was one thing Malcolm Barnett had, it was a good heart.

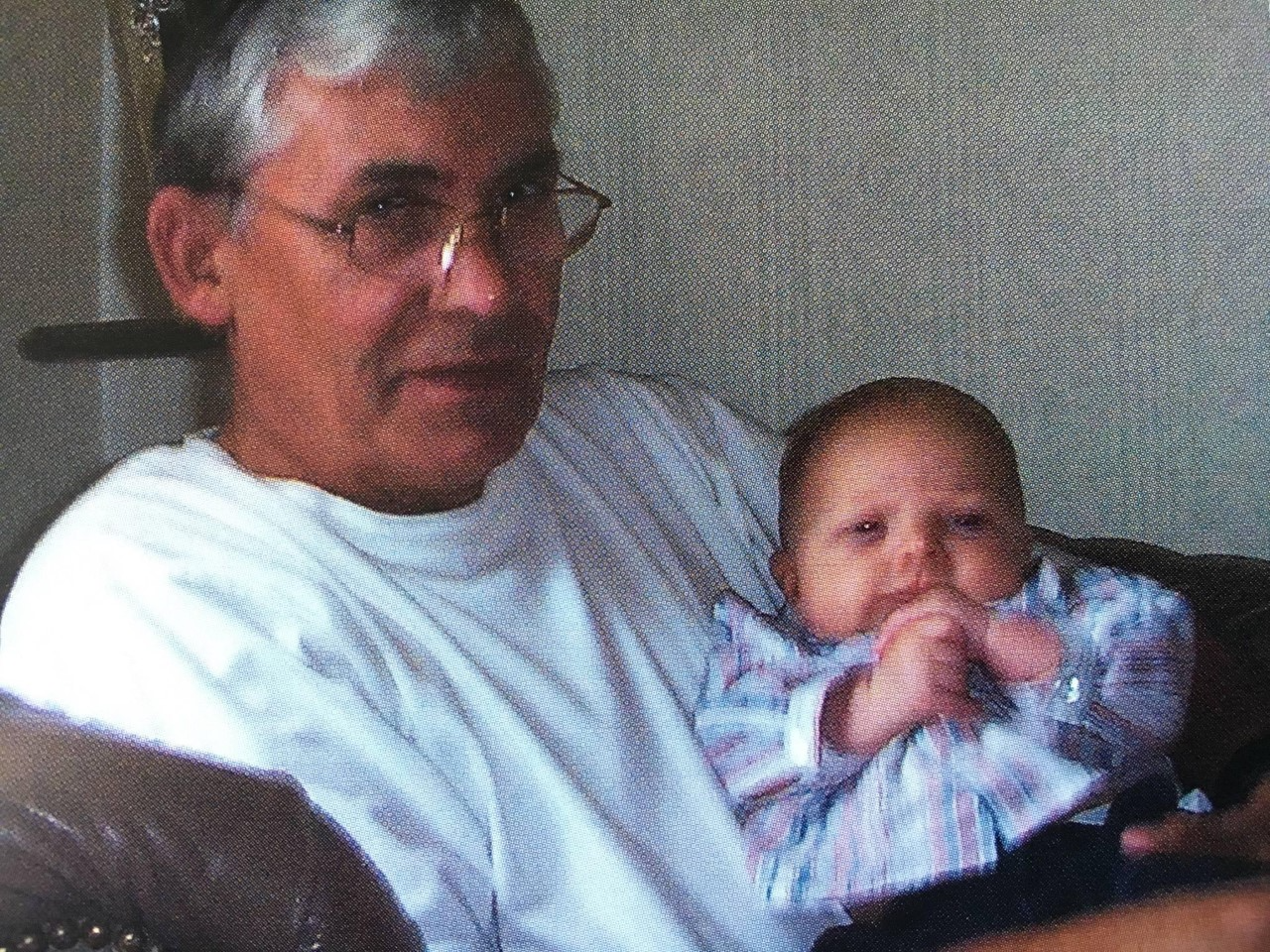

My son Charlie was our firstborn, arriving 18 months before his sister, Alice. For years my dad had, half-jokingly, demanded to know when I was going to make him a grandad. When the day finally arrived, in June 2003, it was as if he had been completed in some way. I can see it now, the two of them playing together on the rug, just feet from where I now write this, when Charlie was just weeks old. My wife whispered: “Look at how he’s looking at him.” There was so much love in Dad’s eyes, I almost felt at that moment that my own gaze was lacking in some way.

Dad loved Alice in equal measure, of course. But this is about the almost curious male thread that winds through our little history, which I had never thought about or considered until now. Charlie was named after my dad’s father, who died when I was 20, when I had not long since started my first newspaper job.

Charlie Barnett senior was a quiet yet loving man, with a shock of dark curly hair, naturally tonsured like a monk. I called him Friar Tuck in mischievous moments, and he always wore a flat cap and a tie with his shirt, even when taking his regular two-mile walk, well into his seventies, to the municipal swimming baths and to pick up a large brown paper bag of porridge oats from Wigan market.

He worked at Westwood power station, and took me there on an open day, where he tried to explain electricity generation to me. He died a few weeks before they dramatically demolished the cooling towers as they started to decommission the site.

As a young man he had been plucked from his mainly mining community on the edge of Wigan and sent to Burma. He was a Chindit, one of the Forgotten Army fighting the Japanese in the jungles. He did his training in India for a while, and there is a grainy photograph of him somewhere, standing in front of the Taj Mahal. I used to sit on the sofa with him in the house they rented that bordered onto some train maintenance sheds, where I could hear the diesel engines chugging comfortingly through the night when I stayed over in their spare room. I would ask him about the war, wanting to be thrilled by real-life stories that were better than my Commando comics. He never really spoke much about it, apart from odd snippets: one time he was walking on patrol in the jungle when the soldier at the head of the column raised his hand, and they all had to crouch down in the undergrowth and watch a column of Japanese soldiers sailing along a rudimentary path on bicycles, as silent as ghosts.

When he had the stroke that would claim his life, he whispered to my nan from his hospital bed: “I know why this has happened to me. It’s because I had to kill that Jap.”

Looking back, I had the same easy, loving relationship with my grandad that my dad had with my son. I don’t remember being particularly upset when I got the news that he had died, until I emerged from the little chapel in the cemetery to see dozens of people there, men he had worked with, who had been unable to get inside, and I crumpled and had to lean on my mum for support.

When my wife picked Charlie up from school on the day my dad died, she wasn’t prepared for the sudden, violent outpouring of grief from him, right there in the car on the road outside school. He crumpled, just as I had done when my own grandad died, and leaned on his mum for support, just as I had. A couple of days later I took him for a walk in the woods near where we live, tramping through the first autumnal leaf falls and not speaking about it, until we did, and I asked him how he was feeling about it all.

I do not feel I did right by my dad, and I do not feel I have done everything right by my son. Or at least, I feel I could have done more

“We could have seen him,” he said, with an edge of bitterness. “Last week. We could have seen him.”

My parents never saw enough of my children. Work and school and busy lives and a dozen other excuses I could make. The week before my dad died, I made a rare foray to Wigan with Charlie, but not to see them. For a couple of successive years we attended a Laurel and Hardy convention with a friend of mine and his son, a bit of male bonding over – for the dads – a few pints. After the event, we got a lift with a photographer who had covered the day, back to Wigan station where we would head to my friend’s home on the Fylde and spend the rest of the weekend with our families. Our route took us directly past my parents’ house.

“Duck down!” I said, full of beer and bonhomie. “If they see us we’ll have to go in!”

We laughed and hid on the back seat, the fez hats we had worn at the Sons of the Desert convention no doubt bobbing comically in the car windows.

It didn’t seem so funny as we stood in the woods in the failing light as summer gave way to autumn. It was weighing on Charlie’s mind. I had robbed him of one final chance to see my dad before he died. Of course, nobody could have known that at the time. Or at least, that’s what I told myself. Because I never thought for one moment that things would change – or at least, that they could change so brutally and so quickly.

The accepted way of things is that a father teaches his son how to be a good man, and then his work is done; and that son might go on to have children of his own, perhaps a son himself, and he will teach him how to be a good man; and that is how life progresses.

But that thread, that cord, that line of progression, it feels all tangled and mixed up for me. What does it even mean to be a man in 2021, let alone a good one? And if I have to ask that question, how can I possibly teach my son to be one?

My dad was a good man, and he loved me, and he did all the things right, even in tough times. And there were tough times. He worked hard, often seven days a week, maintaining a self-employed building business, through recessions and depressions and times of very little money. And he always did the best he could, and it was always enough. One year, when he had been working for a company for a while, he got laid off, just before Christmas. I had wanted a ZX Spectrum computer that year, and I was gently told that things were difficult. On Christmas morning I had a package, and it was indeed a ZX Spectrum. But not in its original box. I don’t know where it had come from, or how, and it obviously wasn’t brand new. But I said nothing, because I didn’t care, and perhaps for the first time got an inkling that whatever happened, my dad would do the best for me that he possibly could, and I think I learned a lesson that day.

I do not feel I did right by my dad, and I do not feel I have done everything right by my son. Or at least, I feel I could have done more. I don’t doubt my love for either of them at all; but is that enough, even if it is a boundless thing, if it is not in some way sharpened and honed into something practical?

And now, perhaps too late, I realise I have lessons to learn from both of them, even though dad is gone and Charlie has left. Perhaps, right at the final moment, I have had some kind of epiphany. I can, perhaps, untangle the knot I have tied in the thread of my lineage, with help from both of them.

Five years ago, I lost my dad. I had indeed been careless. I had misplaced him. I had let him wander off. It is only now that I am finding him again, even as I let go of my son.

I have never felt my father’s ghost more keenly at my shoulder. Perhaps because at last I have let him come to me, to watch as his grandson goes off to make the world for himself, and let the world make him. To watch that with me. Even as I sit here, typing, and although there is not another male presence from that fragile Barnett line, perhaps I am not alone after all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments