Can we say Britain has reached the end of the Covid pandemic?

After two years of death and disruption, the UK has emerged from the darkest depths of the virus. But could a future variant cause fresh problems? Samuel Lovett speaks to the experts

It’s been a long time since concern around Covid-19 dominated the headlines – and with good reason. All the key metrics that many of us pored over during the last two years are now pointing in the right direction; the UK’s vaccination wall has been built high and strong; and the lifting of restrictions has not led to a feared resurgence in infections.

Although the pandemic continues to burn in some other countries, for Britain it appears to have died down to a smoulder, raising hope that we are through the worst of Covid.

But can we confidently say that the UK has reached the end of its epidemic? Are we moving into a state of equilibrium with this virus? Or are we simply exiting the latest Omicron wave and entering into an interval phase, one that will inevitably be disturbed by the emergence of a new variant?

There is much to consider: the current state of immunity in the population and the extent to which it wanes over time; the continuing evolution of the virus; our “post-pandemic” behaviour in society; healthcare pressures; potential seasonal surges; and the long-term fallout from infection.

Arriving at where we are today has not been without pain and suffering. More than 175,000 lives have been lost, with the government’s initial mishandling of the pandemic contributing to that total.

Having emerged from the darkest depths of our Covid experience, the UK has now attained extensive “hybrid immunity” in the population, says Professor Irene Petersen, an epidemiologist at University College London.

Through a combination of injection and infection, the vast majority of us have built up high levels of protection, which has been further diversified and strengthened through repeated re-exposure to the virus, stretching all the way back to the beginning of 2020.

As a result, around 99 per cent of the UK population has developed Covid antibodies, according to estimates from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

While research shows that an individual’s antibody count decreases over a relatively short period of time, leaving them vulnerable to reinfection, the immunological defences involved in protecting against serious disease – such as T and B cells – are much more longer-lasting. It’s this side of our immunity which works to keep us out of hospital.

“One of the things that’s fundamentally different now compared to two years ago is whatever new variants we experience, they are appearing against the background of a population in the UK that is extremely highly exposed [to the virus],” says Professor Mark Woolhouse, an epidemiologist at the University of Edinburgh.

Should a potential new variant of concern prove more resistant to our immune systems and more deadly, the UK — and the rest of the world — may well be thrown back into the trenches

Whereas the original virus was swift to move among the population, which had never before encountered such a pathogen, subsequent variants have each come up against ever-increasing degrees of resistance from the human immune system, denting their ability to cause serious illness.

Future variants will therefore “have to deal with even higher levels of immunity because of all the people who've been exposed to Omicron, which is a very large number indeed,” adds Prof Woolhouse.

That a new variant might emerge is not disputed. The virus has already shown its capacity to rapidly evolve and adapt to humans, displaying a genetic dexterity that has taken experts by surprise. Many thought Delta represented the “peak fitness” of the virus, but was quickly displaced by Omicron, which itself has become more and more transmissible via multiple sub-variants.

“Many virologists, including myself, have been surprised at how much evolution has actually happened with this virus, where we thought it was a relatively genetically stable virus,” says Professor Deenan Pillay, a virologist at UCL.

How much further the virus can evolve remains contested — and it’s not clear what characteristics the next variant will possess. If it acquires new mutations which allow it to circumvent the vaccines and those parts of the immune system responsible for preventing an escalation in severe disease, then there could be trouble.

But so far, this hasn’t really been observed, says Paul Hunter, a professor in medicine at the University of East Anglia.

The vast majority of mutations identified in the variants to date have allowed the virus to evade the body’s neutralising antibodies with increasing efficiency, meaning it has become capable of repeatedly reinfecting us in a short period of time.

But mutations that interfere with T cells, which are responsible for seeking out and killing infected cells, and other immune control mechanisms that protect against severe disease have not popped up with the same frequency, says Prof Hunter. “What we've seen is that these new variants, though they’re more likely to cause infections, they are no more likely to cause severe disease in people who get infected than previously.”

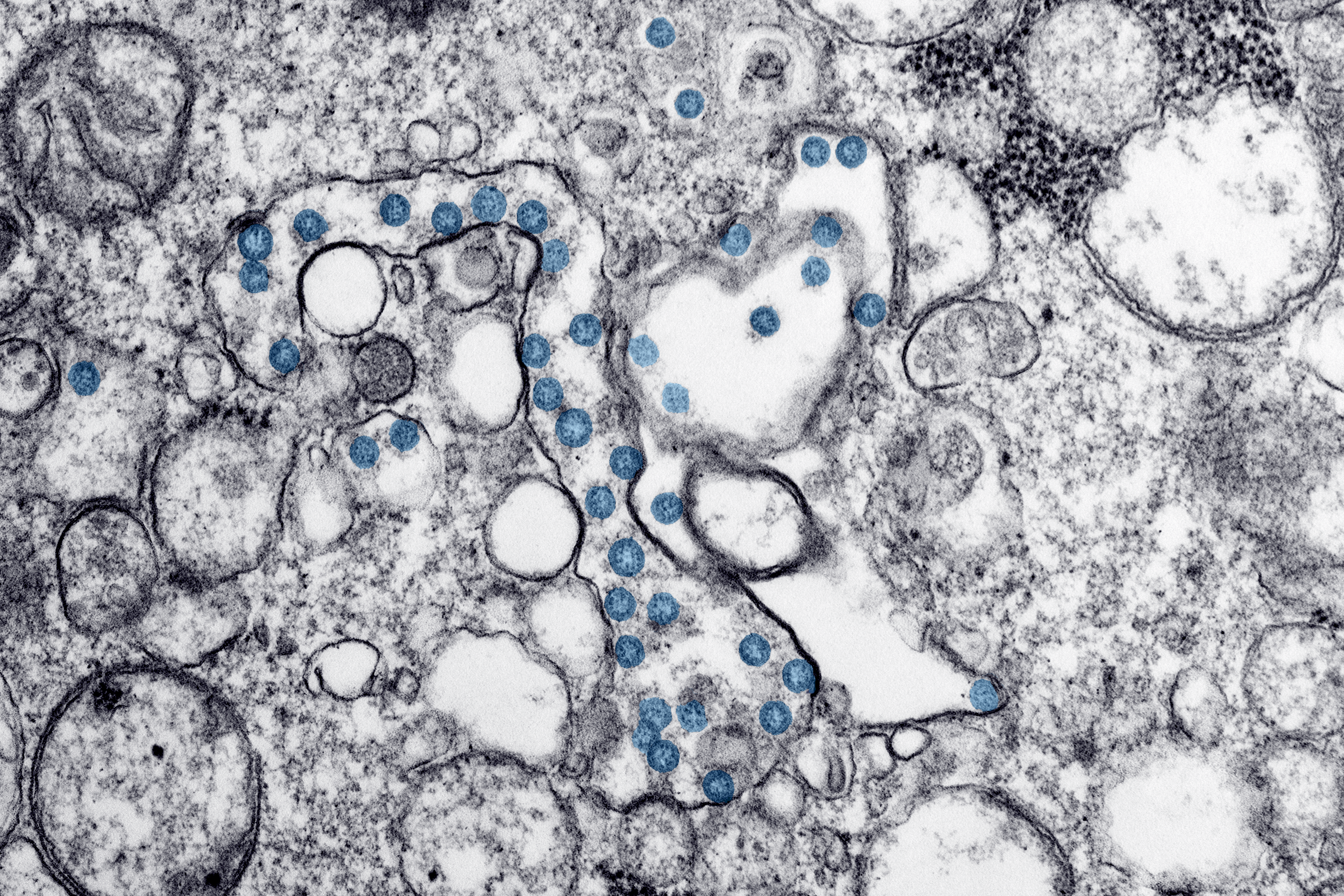

Even so, we are just two or so years into the journey of this virus, says Prof Pillay. Other pathogens, such as malaria and HIV, are still evolving and mutating in humans after hundreds, or even thousands, of years of co-existence. Who knows what turn Covid – know as Sars-CoV-2 – could take in the near future.

Some have suggested the virus will go the same way as other coronaviruses which, over centuries, have become endemic in humans and cause nothing more than a cold – but Prof Pillay warns it’s impossible to know how that equilibrium was reached.

“We’ve not been able to document precisely what happened when those other coronaviruses came into humans, and what evolution they underwent, in order to get to a steady state,” says Prof Pillay. “People need to be reminded that we’re learning as we go along.

“It would be nice to be able to say ‘That's it, we've come to an equilibrium, there's not going to be any more [evolution of the virus].’ But we literally don't know.”

Should a potential new variant of concern prove more resistant to our immune systems and more deadly, the UK — and the rest of the world — may well be thrown back into the trenches. Worryingly, it’s not beyond the realms of possibility.

Although Omicron has proven less pathogenic than its predecessor, both Delta and Alpha caused greater disease than the original virus from Wuhan. Viruses do not evolve in a straight line. They exist in a state of random chaos, throwing up different mutations that open the door to new pathways, some of which allow the virus to flourish, while others are nothing but a genetic cul-de-sac.

“Unfortunately for us evolution is not a finite journey,” says Aris Katzourakis, a professor of evolution and genomics at Oxford University.

“There is still plenty of space for the virus to evolve. As populations acquire immunity, the nature of the selective pressure on this virus changes, pushing it in new directions. Unless viral spread is curtailed, this will not stop.”

Undoubtedly, the next step the virus takes holds the greatest potential to drag the UK back into the acute phase of its epidemic, but there are other factors at play which suggest our fight with Covid is still not quite finished.

With just 18 months of follow-up data on inoculated people, it’s not clear whether the UK’s vaccine wall will continue to stand strong on a long-term basis.

Although the protection provided by jabs appears to be “holding up really well” for now, says Professor Eleanor Riley, an immunologist at the University of Edinburgh, “we can't definitively say how long vaccine-induced protection against disease will last.”

Indeed, data from the ONS shows that people who received their second dose more than six months ago had higher mortality rates for deaths involving Covid-19 than those who had received a second dose less than six months ago. “This indicates a possible waning protection from vaccination over time,” the ONS said.

The question that remains unanswered, according to Prof Woolhouse is whether we’ve now developed a background level of immunity that we’ll keep for many years, possibly a lifetime, or is it going to continue to decay?

“If there is continued decay in people's immunity both, then the vulnerability of the population will steadily increase over time,” he says. “And the more vulnerable we are, in a sense, the more likely it is that a new variant can arise that take advantage of that vulnerability.”

I don’t know how quickly, but the real danger for people with long Covid is that they will be forgotten because they are suffering from a chronic disease

Plans are in place in the UK to mitigate this potential risk through an autumn booster programme, raising the prospect of annual vaccinations to keep our immune systems primed and topped up, but not all countries will have such a luxury.

Prof Woolhouse also questions how the current epidemiological picture will change once the population reverts back to its pre-pandemic behaviour. Even now, we still aren’t interacting with one another in the same way we used to, which will have consequences for how the virus spreads and its wider impact on society.

Data from Google shows that mobility trends for places such as restaurants, cafes, shopping centres and museums down 10 per cent from what they were between January and February of 2020. Mobility trends for public transport and workplaces are also down 25 per cent and 23 percent, respectively.

Seasonal changes will also nudge our epidemic in different directions. As summer beckons, bringing with it warmer weather, more of us will be spending an increasing amount of time outdoors, making it harder for the virus to transmit as easily. As a result, we can expect cases to fall.

In contrast, the winter months will likely see time spent indoors increase again, meaning the current situation could once again worsen in six months – but to what extent remains unclear.

Dr Tom Wingfield, a senior clinical lecturer at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, said the coming winter – and how it plays out – will likely offer a “key indication” of what lies ahead for the UK on a longer-term basis, though scientists remain divided on whether Covid will settle into a flu-like pattern or establish itself as a year-round illness like the common cold.

Nonetheless, most scientists who spoke with The Independent are in agreement that the UK has now come through the worst of its epidemic. Some, however, believe that it is now transitioning into a softer, less visible form which is still exacting a considerable health toll on the population.

The acute pressures posed by hospitalisation and severe illness may be subsiding, but the lingering effects of infection are still prevalent.

Last month, 1.8 million people in the UK had long Covid according to the ONS, nearly 800,000 of whom have been suffering from the condition for at least one year, while 346,000 say their ability to undertake day-to-day activities has been “limited a lot”.

Long Covid is the lasting tail to this pandemic and it shows no signs of fading away. Long-term complications can be neurological, cardiological, gastroenterological and respiratory in nature, making it difficult for patients to live the life they once did.

“The burden of long Covid is going to mount,” says Professor Chris Dye, a former director of strategy at the World Health Organisation.

“I don't know how quickly, but the real danger for people with long Covid is that they will be forgotten because they are suffering from a chronic disease, which is, by and large, not going to put them in emergency wards.”

David Strain, a senior clinical lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School, sees comparisons between the looming burden of long Covid disease and the fallout from polio.

“Nobody remembers the acute polio epidemic. We just remember the after-effects of polio,” he says. “I think in five years’ time, it will be the after-effects of Covid that we remember.”

As many scientists believe, it’s highly unlikely that the sights of spring 2020 and winter 2021 are going to be repeated. At least not by Covid-19

This isn’t to say that people are no longer ending up in hospital and dying because of Covid. Just under 1,000 people were lost to the virus in the last seven days. In February, coronavirus was the third leading cause of death in England, according to the latest figures.

Thankfully, though, its impact on the NHS has lessened from 2020 thanks to a combination of vaccination, “experience and confidence” among staff about dealing with the virus, and the availability of new therapeutics, says Dr Wingfield, who also works as a clinician.

Chris Hopson, chief executive of NHS Providers, which represents trusts in England, said it’s “50-50” in terms of those coming into hospital with Covid and those being admitted because of Covid. For the latter group, the “significant majority are patients who have not been vaccinated,” he says.

Other factors – age, a weakened immune system, obesity, and other underlying health conditions – continue to play a role too, says Prof Woolhouse. And being vaccinated doesn’t completely remove all risk associated with these, he adds.

“I personally would still be concerned about about an elderly frail patient in their 80s with comorbidities, who had been vaccinated, than I would about a teenager who hadn’t,” says Prof Woolhouse.

In general, though, as infection rates drop, the main Covid pressures are no longer posed by the burden of disease itself but instead derive from the residual infection control protocols still required, for example, to separate out infected patients and protect vulnerable patients, says Hopson.

“We just need to remember that if we get the further seasonal outbreaks most epidemiologists say are inevitable, the NHS is still extremely vulnerable to the triple impact we’ve seen over the last few months” he says. “The first impact is the beds taken up by Covid-19 patients, which is likely to increase over winter when the NHS is at its most busy. The second impact is higher staff absences when the NHS workforce has 110,000 vacancies and is incredibly stretched.

“The third impact is on the NHS’s ability to discharge medically fit patients because of the effect Covid has on an already very pressured social care system.”

In light of this ongoing disruption, it’s hard to conclude that the epidemic has run its course, especially for those working in the NHS. Overburdened and overworked staff, many who have been pushed beyond the point of burnout, continue to grapple with the fallout from Covid on a daily basis, even if wards are no longer full of patients dying from the virus.

Understandably, the UK is eager to move on from the pandemic. There is much comfort to take from the current direction of travel, which could feasibly be accelerated by the implementation of light-touch measures, such as improving public ventilation or offering sick pay for those ill with Covid.

While infections, deaths and hospitalisations cannot be dismissed, the outlook for Britain is brighter than it has ever been.

A closer look at the current landscape shows our epidemic is still rumbling on, but we – the public – are certainly justified in turning our gaze forward. Indeed, as many scientists believe, it’s highly unlikely that the sights of spring 2020 and winter 2021 are going to be repeated. At least not by Covid-19.

At the same time, it’d be foolish to believe that Covid is done and dusted. “I’m not at all confident that it will simply get better and go in one direction forever,” says Prof Woolhouse. “I think there will be bumps along the road in the next few years. But I’d love to be pleasantly surprised.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments