Is El Salvador ready for bitcoin to become legal tender?

El Salvador’s ‘bitcoin law’ comes into effect next month, making it the first nation to adopt a cryptocurrency as legal tender. So what does this mean for its people, asks Brian McGleenon

Since US president Richard Nixon took the world off the “Gold Standard” in 1971, global finance has been powered by the fiat monetary system, where money is not backed by anything and created by central banks out of thin air. Therefore, officialising bitcoin as a sovereign currency will have far-reaching consequences and both proponents and opponents are watching eagerly from the sidelines to see how the gamble unfolds. However, caught in the middle of this experiment are the people of El Salvador, and, with only days to go before the law's execution, information about the law is scarce and preparations on the ground are minimal.

The world's major economies are now on the offensive against bitcoin. China has banned it outright and the US plans to choke it into submission with excessive regulatory interventions. The world’s preeminent cryptocurrency emerged from obscurity in January 2009 when the anonymous Satoshi Nakamoto “mined” the first coin of this revolutionary medium of exchange. Since that “genesis block” was first forged bitcoin has grown to be regarded by some as an existential threat to nation-states and global financial institutions. As world trade, social interaction and employment increasingly move online, it seems natural that the virtual world we inhabit for most of our waking hours has an indigenous monetary system and that digital assets, property and even artwork can be allocated specific value.

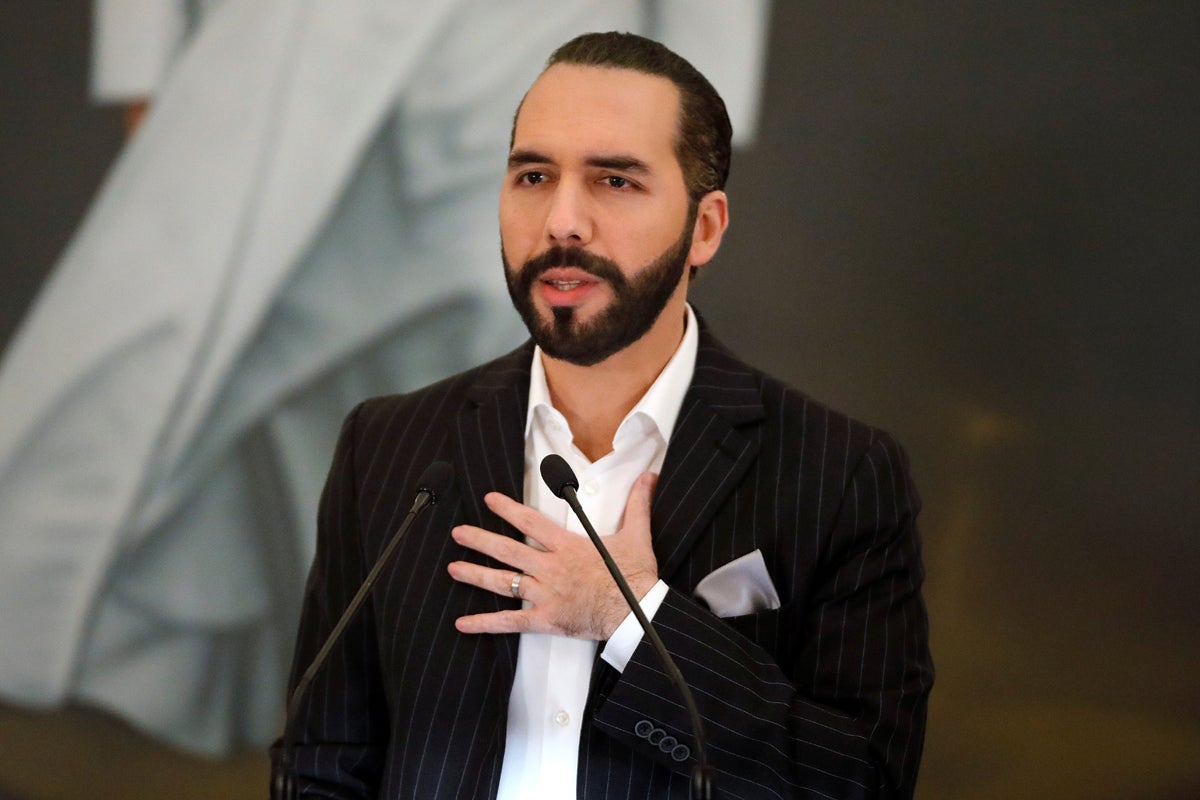

President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador surprised both the centralised capitalists of global finance and the decentralised anarcho-capitalists of the crypto-sphere when in early June he announced that his country would adopt bitcoin as legal tender. The baseball-capped millennial chose the Miami Bitcoin Conference to make his announcement before sending any proposed legislation to El Salvador’s congress. This sowed the first seeds of suspicion back home that his radical plan was more PR stunt than hard policy.

At the bitcoin 2021 conference in Miami on 5 June, he declared: “I will send to Congress a bill that will make bitcoin a legal tender in El Salvador, and in the short term, this will generate jobs and help provide financial inclusion to thousands outside the formal economy, and in the medium and long term we hope that this small decision can help us push humanity at least a tiny bit into the right direction.”

President Bukele’s announcement has started to change how the nation is perceived by the world’s media and thus the minds of its consumers. Before June’s announcement, El Salvador conjured up images of drug trafficking, spiralling homicide rates and political assassination. Now, these old stereotypes sit incongruously alongside a new El Salvador, one that has grasped the reins of a revolution in financial governance that has been compared to the early days of the internet. Currently, bitcoin has approximately 150 million users, similar to what the internet had in 1997.

In a recent interview with bitcoin podcaster, Peter McCormack, president Bukele described his nation as one that is used to following others, but his audacious plan is to make El Salvador a nation that leads. Speaking on What Bitcoin did Next he said, “El Salvador is not usually recognised as the first country to make innovations, but why not this time?”

Influential US business executive Michael Saylor has praised president Bukele for his initiative, but quieter voices from within El Salvador are apprehensive because they will be the guinea pigs involved in the world’s first experiment in using bitcoin as a sovereign currency. Nelson Rauda Zablah, a journalist with Salvadoran news outlet El Faro, helped me empathise and said, “it is easy to cheer the president and the bitcoin law from the sidelines and watch El Salvador’s economy thrown into a virtual casino. But, what if it was happening in your country, what if it was your business, your credit rating or your pension scheme, or your savings at stake?” Travelling through El Salvador, in the last days before the bitcoin law comes into effect, I discern a nation divided into three groups; those who oppose the law and believe the nation is on the verge of an unprecedented economic disaster, those who support it and believe the nation is on the cusp of a great leap forward, and a sizeable portion of the populace that when asked about the issue shrug and say, “bitcoin, what?”.

Growing political opposition to the law has rallied around the #NoAlBitcoin Twitter hashtag (no to bitcoin), with business leader Javiar Siman warning that “bitcoin is a threat to the well-being of our workers and the economy in general”. The opposition has questioned the haste in which the president rushed the law through the nation’s legislature, with the banking sector and lawmakers having only a sparsely detailed three-page document to ponder over. Those who support the president argue that he had to act fast as global financial institutions, allied with the mechanisms of bureaucracy within El Salvador, could have smothered the law to the point where it would have been delayed ad infinitum. However, there is one common trait shared by all three groups, the bitcoin law has unintentionally forced people to consider the essence of what money actually is, what gives it its value, and why one currency is worth more than another.

Beyond El Salvador’s shores, the world of international finance is beginning to become unsettled lest the bitcoin gamble succeeds and causes a domino effect of copy-cat nations. A world that begins to place value on bitcoin would in turn dilute the value of the fiat currencies printed by central banks, and ultimately endanger the nation-states that they represent. The heads of international finance have painted a picture of woe if El Salvador presses ahead with its plan. After president Bukele made his announcement, Agustín Carstens, head of the Bank for International Settlements, told German media outlet Der Spiegel that “bitcoin is only good for two things, speculation and ransom payments”. The warning was bolstered by Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, who threatened there would be a series of “tough love” responses from the world of international finance if El Salvador actualised its Bitcoin law.

Already there are signs that El Salvador could now be frozen out of aid from the IMF and World Bank, and quite possibly made an example of. The World Bank rejected a request by El Salvador for funding to implement its bitcoin law. The institution, which was founded in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944, answered president Bukele's request with a brief note in French stating, “fin de non recevoir“, thus articulating their absolute refusal. The World Bank was co-founded by British economist John Maynard Keynes, who promoted fiat currencies that allow governments to issue new money that is not backed by anything of value. This is the antithesis of bitcoin, which can only ever have a finite supply of coins, 21 million in total, with each one produced at an increasingly difficult rate via computer processing power.

Steve Hanke, the former economic advisor to Ronald Reagan, has been notably vocal in his warnings to the Salvadoran government. He recently expressed his reservations to Nelson Rauda Zablah of El Faro, warning that for El Salvador, “you’d have to be insane to introduce bitcoin into an environment that’s already corrupt.” Hanke knows the territory as he was the architect of currency reform in many Latin American economies, El Salvador included. His solution to the unstable sovereign currencies of the region, or “junk currencies” as he referred to them, is to either peg them to the dollar or scrap them and use the dollar only. His arguments for global dollarisation were accepted by El Salvador in 2001 when the nation ceded its monetary control to the US and accepted the dollar as its legal tender. From president Reagan’s interventions that prolonged the civil war to the nation’s dollarisation in 2001, El Salvador has had a complicated relationship with the US.

Over two million Salvadorans reside in the US and send remittances back to their home country that accounts for 24 per cent of El Salvador’s GDP. However, a sizeable proportion of this money is taken by intermediaries such as Western Union that charge a 10 percent fee for wiring the dollars home. Jack Mallers, the founder of the Strike bitcoin payment application, which is available only in the US and El Salvador, told the Investors Podcast that instead of sending dollars through Western Union, remittances could be sent through bitcoin using the Strike app that “will offer free and instant remittance payments, of any value, at any time”.

Traditional banking has failed a large segment of Salvadoran society, where 70 per cent of the population does not have a bank account, and thus access to finance which is a precursor to an improved material wellbeing. According to the UN large parts of rural El Salvador “have been historically neglected by traditional providers of financial services”. The government’s answer is to use the bitcoin law to promote “financial inclusion” by offering each citizen a digital wallet containing $30 worth of bitcoin. The “Chivo” wallet will immediately allow every adult to accumulate bitcoin as a digital asset. This could see a great transfer of wealth to the lower strata of society if bitcoin appreciates as it is forecasted to do so and reaches a speculated value of $100,000 per coin by the end of 2021. Also, El Salvador’s central bank will begin to hold bitcoin as an official reserve asset, which could be reflected upon as a prescient move in the future. The new law obliges banks operating within El Salvador to accept bitcoin as payment on loans or deposits. This will force global banks to enact procedures for handling bitcoin within El Salvador, and so the cryptocurrency will flow into the veins of global finance through the back door.

The move could also encourage other central banks to accumulate bitcoin as a finite store of value, akin to gold. Proponents hope that this will eventually lead to world currencies becoming pegged to bitcoin, thus manifesting a new monetary system, “the Bitcoin Standard”. This would in turn see a gradual dissolution of the disproportionate unelected power that managers of central banks have had over the years through their ability to issue unlimited volumes of fiat currencies. Bitcoin maximalists point to the fiat monetary system as the cause of much of the world’s ills. Unpopular wars can be prolonged with printed money when a nation’s citizens have lost the appetite to pay for them through taxes. The Vietnam War has been cited as an example of this. However, bitcoin pioneer Max Keiser tells me that the world’s preeminent cryptocurrency fixes this because it “is held behind an impenetrable, encrypted wall inaccessible to any corporation or government. People who object to how governments are printing money from nothing and waging wars without end, are opting out of the system by converting their paper money for bitcoin.”

If president Bukele succeeds in what Steve Hanke has called “his crypto fantasy” Ray Youssef, CEO of Paxful, told CoinDesk that “El Salvador will become the Switzerland of Latin America”. However, a stroll around downtown San Salvador illustrates the difficulties ahead. The centre of El Salvador’s capital city is dominated by the Metropolitan Cathedral, where Oscar Romero preached his homilies of social justice at the outbreak of the nation's brutal civil war, which lasted from 1979 to 1992.

Bitcoin is coming and we can’t stop it, this is like smashing a clock to try and stop time

Beyond the recently refurbished central plaza and its patrols of military police the streets begin to narrow, the buildings appear time worn, and the roads and pavements are crammed with a multitude of street vendors. In these impromptu markets, everyone is transacting with physical dollars. There is no evidence of the tools of digitised finance needed for bitcoin transactions, such as card machines, ATMs and smartphones. This will present a challenge for article seven of the bitcoin law that states, “every economic agent must accept bitcoin as payment when offered to him by whoever acquires a good or service”. This makes bitcoin not only legal tender but also compulsory tender in El Salvador, an aspect of the law that has caused the most controversy.

The opponents argue that forcing people to accept a highly volatile asset such as bitcoin could lead to mass bankruptcies, especially for small businesses that do not have the financial reserves to cover losses if the cryptocurrency market goes into a downturn. A former government official stages a regular protest against the bitcoin law in downtown San Salvador. Eugenio Chicas is the main organiser of a sticker campaign, where he places No Al Bitcoin stickers on market stalls in the streets surrounding the Metropolitan Cathedral. When I inquired about one of the stickers a market trader stated that she “has never used an ATM to withdraw money, my customers pay me in cash, I am not used to this bitcoin technology“. However, another market customer implied the stickering campaign was futile and said, “bitcoin is coming and we can’t stop it, this is like smashing a clock to try and stop time.”

Bitcoin is inherently digital and relies upon internet connectivity for transactions. In a nation such as El Salvador where internet connection can be poor or non-existent, and many people have no access to smartphones, attempting to transact using bitcoin with small businesses or market traders could be met with a lot of frustration. Approximately 58 per cent of Salvadorans have access to the internet, and in the markets around the Metropolitan Cathedral in downtown San Salvador, many people shook their heads in opposition to the idea of using the cryptocurrency. The time taken to settle a transaction on an antiquated mobile device with wifi periodically cutting out would see a quick return to physically grasping a dollar note and placing it in the recipient’s hand. When I mentioned the markets around the Metropolitan Cathedral to Nelson Rauda Zablah, he said, “this is not a digitalised society where everyone pays with cards or mobile phones, not many people even have a bank account, trying to throw bitcoin into an environment like that draws suspicion.”

Suspicion about the bitcoin law has been inflamed by the scarcity of public information trickling down from the president’s office. The Salvadorans that I spoke to, whether they worked in banking or the service sector, were equally in the dark about the finer details of the law and how it will manifest in society. President Bukele is an avid social media user, and information about the bitcoin law seems to come randomly via his Twitter account, or through online live streams in English with foreign investors. In both cases, the intended audience seems to be located beyond the confines of El Salvador. He seems to have designed the law with the help of two unelected advisors, his brothers Ibrajim and Yusef. It is not clear whether the companies being brought in to roll out the monetary infrastructure to enable bitcoin as legal tender have bid for contracts as would be expected for public infrastructure schemes.

Two US companies, bitcoin ATM maker Athena and Jack Maller’s Strike payment service have been contacted directly by the Bukele brothers. Jack Maller is also the developer behind the “Chivo” digital wallet scheme. The Bukele brothers are precious about their vision and there is the sense that they need to act fast and implement the law, whilst they have the attention of the crypto-sphere, lest another nation slips ahead of them. President Bukele is on a mission to “design a country for the future” and to hand over his vision to the compromises of the democratic process or the cynicism of banking regulators is not an option he seems willing to take. But the lack of transparency has led to speculation that there is no grand plan and that “it’s all fake”, as one El Salvadoran told me. They added, “it’s all smoke and mirrors, but it has worked in one way, it has brought you here to spend your tourism money.”

Ironically, much of my “tourism money” was in bitcoin. As along the coastal areas centred around the resort of El Zonte, bitcoin has been living side by side with the dollar for several months already, the result of an experiment propagated by Mike Peterson, the director of Bitcoin Beach. The volunteers of the Bitcoin Beach project have been gradually spreading their influence from their core at Hope House in El Zonte. The scheme has been successful and the majority of local businesses are transacting with Bitcoin with ease, from small corner shops to large hotels and supermarkets.

The success of bitcoin in El Zonte should be studied by the Salvadoran government and possibly emulated on a national scale. While using the Bitcoin Beach payment app in El Zonte, I was able to purchase food, transportation and accommodation instantaneously and with no transaction fee. An achievement I would not have been able to do with my Visa card. On top of this, the small amount in bitcoin that I used for my own experimental purpose on the trip had gained 10 percent in value during my stay. However, one taxi driver from the region, used to functioning in both currencies, warned me that the bitcoin price “is a roller coaster” and could drop again at any time.

The volatility of bitcoin is a major hurdle causing many to hesitate before they’d accept payment, never mind their monthly pay-cheque, in the cryptocurrency. However, the Salvadoran government has set aside a trust fund of $150m to protect businesses and individuals if there is a sudden cryptocurrency bear market. This trust fund guarantees that anyone using bitcoin can convert the amount that was traded into the dollar amount at the time the transaction took place.

Most of the president’s grand schemes attached to the new law seem very progressive and have caught the imagination of the world’s media, but are they hypothetical? Two proposals stand out. The president announced that geothermal energy from El Salvador’s many volcanoes will be utilised to power domestic bitcoin mining operations. On 9 June the president tweeted: “Our engineers just informed me that they dug a new well, that will provide approximately 95MW of 100 per cent clean, zero-emissions geothermal energy from our volcanos. Starting to design a full bitcoin mining hub around it.” However, according to Nelson Rauda Zablah: “the bitcoin mining stations don’t exist, this is the cherry on top of the absurd things that the president has announced.”

China recently banned bitcoin mining, and in one stroke took 70 per cent of global mining operators off-line. The consequences have been positive for miners in other parts of the world, who now don’t need to use as much processing power to mine each bitcoin, and so revenue from mining has been booming. If the Salvadoran government is serious about facilitating a domestic bitcoin mining industry they should act quickly to capitalise amid this time of less competition and higher profitability. Another idea that was formulated by the president and expressed during an online conversation hosted on Twitter was that El Salvador would grant permanent residency for immigrants that invest three bitcoins in the country. However, I was informed by Nelson Rauda Zablah that there have been no official discussions on this promise, and no changes have been made to the nation’s immigration law.

A recent survey by Deloitte revealed that 76 per cent of financial experts think digital assets such as bitcoin and ethereum could replace fiat currencies within 5 to 10 years. As the cryptocurrency sector quickly innovates, central banks are in a desperate race to catch up. But this is a race that they may well lose as they are reacting rather than innovating, this is illustrated by reports that central banks are developing their own digital currencies and online wallets. With the advent of El Salvador’s bitcoin law, the country is showing that it is positioning itself to surf rather than buckle against the coming disruptive wave from the cryptocurrency revolution. Bitcoin has been called the “gateway drug” to the world of decentralised finance and president Bukele’s brother, Ibrajim, has already stated that the new law is “just the beginning. In the future, we’d like to make all cryptocurrencies legal tender.”

No other nation-state is presenting this willingness to embrace cryptocurrencies and decentralised finance, which are one of the hallmarks of web 3.0. President Bukele said he wanted to make El Salvador first in the world at one thing, it could become the first nation to leave the old world order of cash, fiat currency, and central banks, and step across the threshold into the age of decentralised finance and cryptocurrency. Antoni Trenchev, co-founder and managing partner of Nexo, told me that El Salvador is “putting sovereign adoption of bitcoin” on the map and that “we may well look back at this time as one of the most important moments in cryptocurrency’s history.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments