The cook who has spent 50 years making vegetables as exciting as meat

In the 1970s, Deborah Madison set out to make vegetables seem less drab. Julia Platt Leonard looks back at the journey of one of vegetarianism’s most important chefs

A new butcher shop opened near where I live in north London. It’s got everything you’d expect from a traditional butcher: a thick wooden butcher block, glass-fronted display cases, tiled walls and stainless steel counters – the butchers even wear traditional striped aprons and straw bowler hats.

It’s got everything you’d expect from a butcher except for one key ingredient: meat. It’s a vegan “butcher” with not so much as a sausage (unless you count “soysage patties”) in sight. There is bacon, pastrami and even black pudding, but made from plants, not animals.

I can’t help thinking, why can’t vegetables just taste like – well –vegetables?

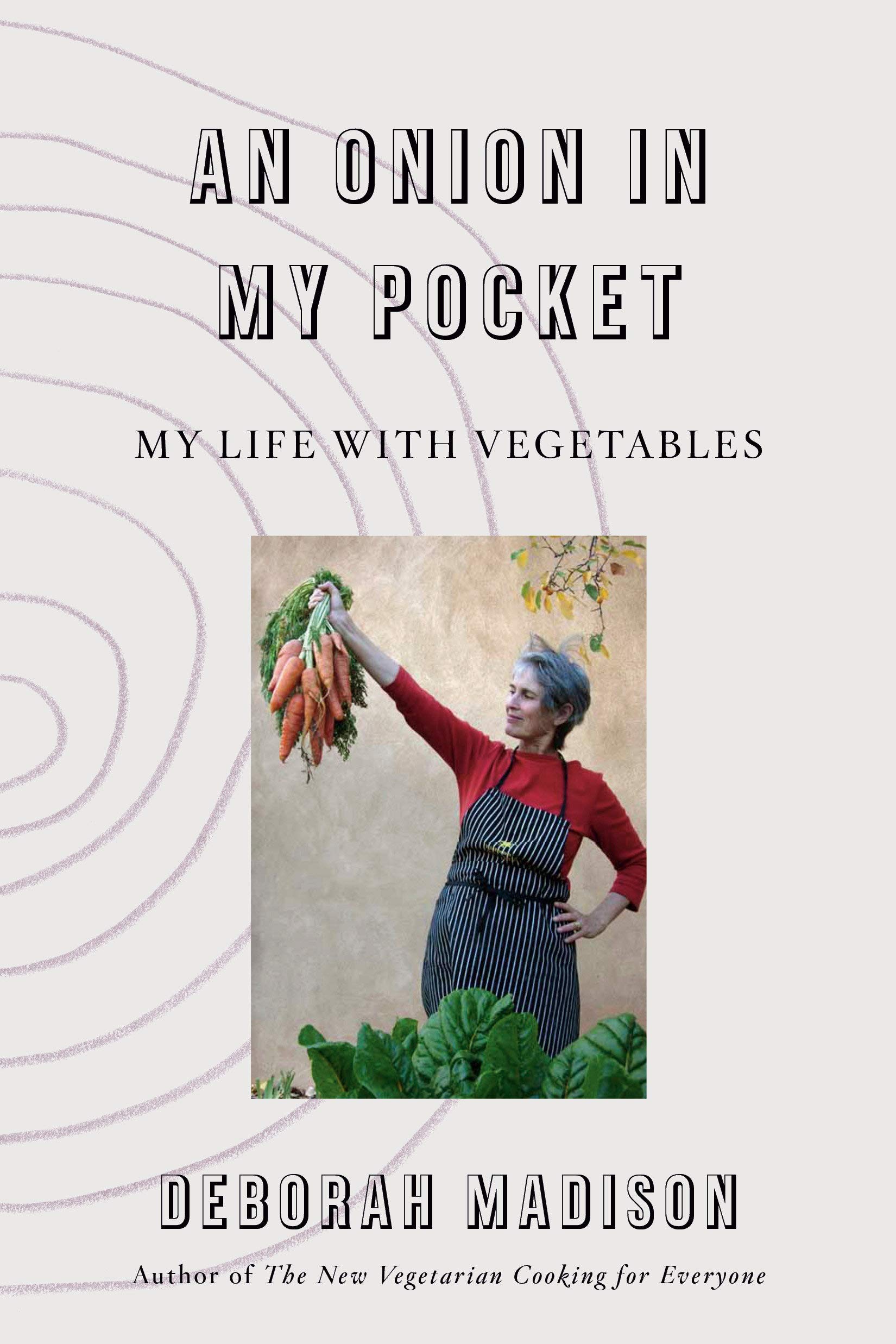

The answer is they can. And if you ever need a reminder, then flick through any of Deborah Madison’s 14 cookbooks. Madison is better known in the US where she’s from, but for anyone interested in vegetarian cooking – scratch that, cooking full stop – she should be top of their cookbook wishlist. And with the publication of her memoir An Onion in My Pocket: My Life with Vegetables, there is a welcome opportunity to learn more about her journey from Zen student in San Francisco to restaurant chef, award-winning food writer and champion of small farmers and farmers’ markets.

And while you might find her work in the vegetarian section of a bookstore she doesn’t consider herself a vegetarian. In Onion she says: “Say the word ‘vegetarian’ and there’s always this uncomfortable pause that suggests you are not quite a legitimate eater, much less a legitimate cook.” Friend Elissa Altman, author of Motherland and Poor Man’s Feast, agrees. “She is not an ‘ism’ person – she doesn’t believe in vegetarianism, or veganism, or meatism. She, I think, believes in true food, real food, in knowing where it comes from, and honouring it and the people who produce it.”

Madison grew up on a dairy farm in upstate New York before moving with her family (she has three siblings) to Davis, California, in 1953. Both parents lived through the Great Depression but both of their fathers were employed and never went through breadlines. Still, Madison’s mother “cooked and ate from a sense of scarcity that was largely imagined”, she writes in Onion. Madison learned to read menus by price, searching for the least expensive dish, usually an egg salad sandwich. Even in her old age, Madison’s mother would spend less that $20 a week on food, “shakily walking from Safeway to Longs because the eggs were a few cents cheaper there”. (This despite the fact that Madison’s bother was an organic farmer and would drop off eggs for their mum.)

As I read An Onion in My Pocket, I waited for the moment when Madison knew she wanted to work in food (her first ambition as a child was to be an ornithologist) but instead found a series of epiphanies. There was the college graduation dinner she prepared: “I covered a huge platter with boiled crabs, asparagus and artichokes and doused it all with lemon vinaigrette and fresh herbs.” It’s an early version – a work in progress, if you will – of the many platter salads she’s created throughout her career.

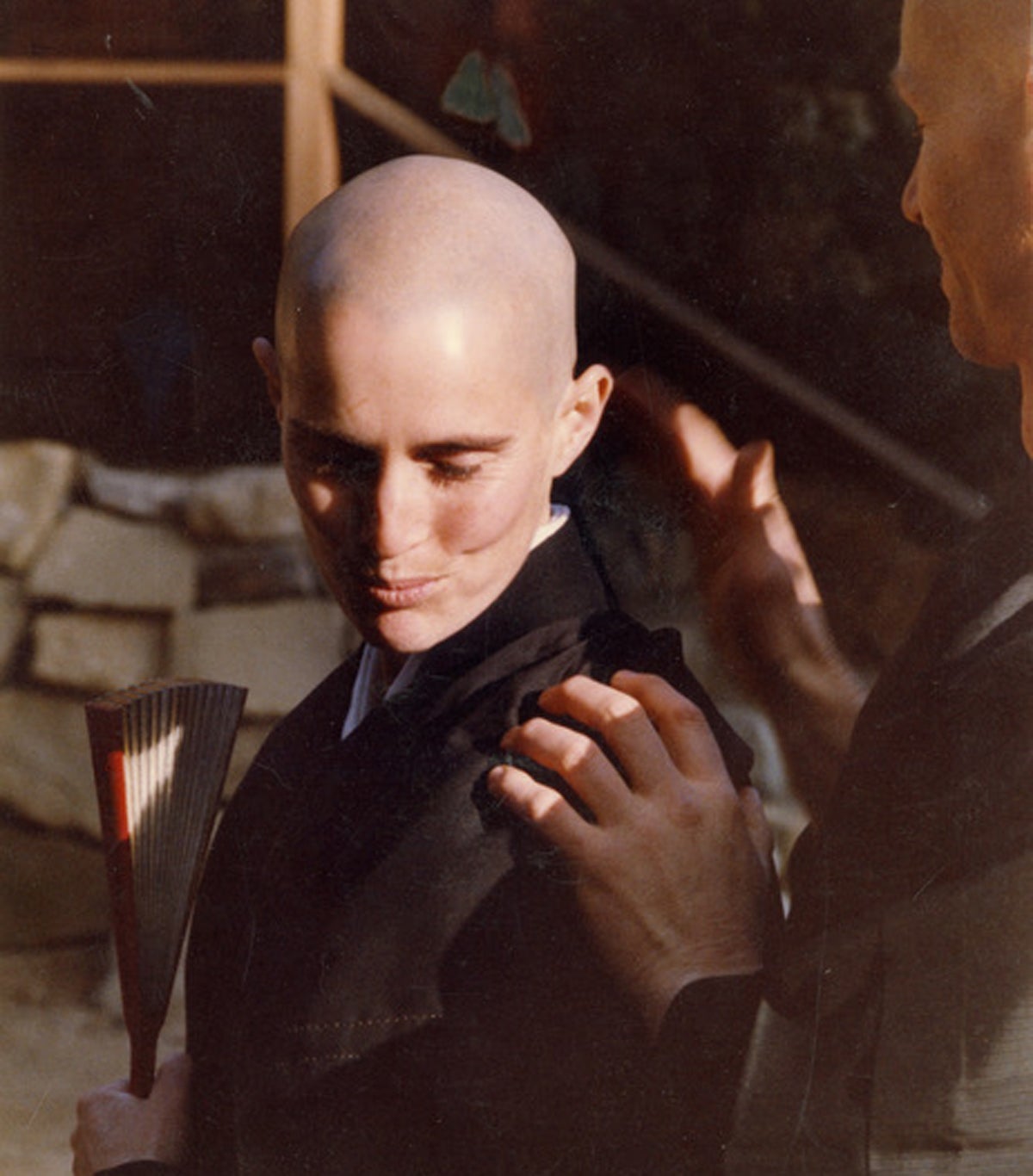

There were the “foreign” dinner parties her parents hosted that were inspired by The European Cookbook for American Homes by “the Browns, Cora, Rose and Bob. Later came the Time Life Food of the World Series and her favourite volume, The Cooking of Provincial France and for her, a glimpse into what food could be. But it was in 1970 when Madison started cooking in the kitchens of the Zen Centre in San Francisco that some of the themes of her career, including an interest in plant-focused cooking, started to emerge.

Madison studied at the Zen Centre for almost 20 years, and spent much of that time cooking for her fellow students. When she started, the food was plain, basic – nutritious but hardly inspiring. Gradually she started adding butter and cheese, baking powder to the pancake batter, and spice. In Onion she says: “Even if I was going to cook vegetarian food, couldn’t it also be good enough to be exciting, if not transporting?” Unlike today, there weren’t many vegetarian cookbooks so Madison sought inspiration from non-vegetarian books like the The Joy of Cooking, Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking and James Beard’s books on American food. “I often found that if I looked hard at a meat-based recipe, I could ferret out some aspect of it that could be translated into a meatless dish.”

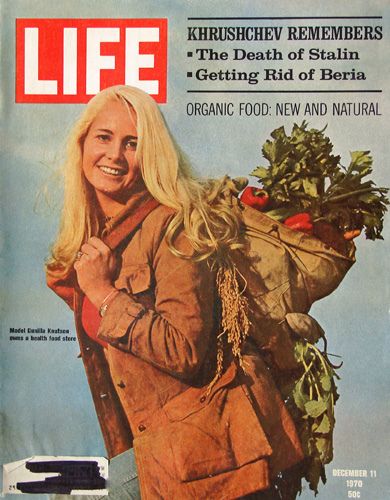

Vegetarian cooking and vegetarianism weren’t new but they were niche in 1970. Madison writes that someone recently sent her a copy of Life magazine from December of that year. On the cover was a healthy-looking young woman with long blonde hair, a sparkly smile and a backpack full of vegetables. The story inside led with the headline, “The Move to Eat Natural: new converts to organic food are sprouting up all over”. It included a photo of different loaves of uniformly brown bread photographed on a brown background. The baguette looks sturdy enough to use as a cricket bat and the round loaf would double nicely as a door stop.

The message? Vegetarian food – healthy food – is “good” food, earnest and not a lot of fun. “I caught myself asking,” Madison writes, “Wasn’t it meat that was the brown food? Why did we have this idea that vegetarian food has to be so drab?”

It was a dinner at Chez Panisse, the now iconic restaurant started by Alice Waters in 1971, that showed Madison what food – not only vegetarian food – could taste like. Madison went there with her future first husband Dan Welch, another student and cook at the Zen Centre. “It was the goat’s cheese that did it at that dinner,” she writes. She recalls the menu – the ragout of seafood with green-lipped mussels in a saffron and tomato broth, the lamb with turnip gratin, a salad of baby lettuce, that goat’s cheese, and a host of desserts including pastry chef Lindsey Shere’s signature raspberry tart.

“It was as if I were on another planet and I realised finally that this was the food I’d always wanted to eat,” she writes. They went back to the Zen Centre and told the abbot they wanted to work at Chez Panisse. Food writer David Tanis worked at Chez Panisse at the time. “Deborah worked in the pastry area and Dan worked with me in the cafe, making pizzas. They were both very friendly and fun-loving, but also serious hard workers. We became fast friends.” With Tanis, they’re some of the illustrious alumni who have worked at Chez Panisse over the years – others include chefs Jonathan Waxman, Jeremiah Tower, Suzanne Goin, April Bloomfield, Dan Barber and Mark Miller.

Madison describes what feels like a magical place – not only the food but everything from the way the tables were laid to the letterpress menus made by Patricia Curtan (she also did the artwork for Madison’s cookbook The Savory Way). It was, as Madison describes it, a “spirit of plenty” and a world away from what she’d experienced growing up. “At Chez Panisse there was never holding back. If something ran out, there was something better to take its place,” she writes.

It was as if I were on another planet and I realised finally that this was the food I’d always wanted to eat

In the late 1970s, the Zen Centre asked Madison to be head chef at a new restaurant on a piece of property in Fort Mason that looks out onto the San Francisco Bay. The building had a wall of glass and a panoramic view of the bay and the Golden Gate Bridge. It would feature a vegetarian menu and much of the food would come from the centre’s Green Gulch Farm in Marin County. So they decided to call it simply Greens.

The cool, foggy climate at Green Gulch was ideal for growing lettuces, fingerling potatoes, pumpkins with exotic names like Rouge Vif d’Etampes, edible flowers and leafy herbs. They grew things like sorrel and rocket, golden beets and Chioggia beets with their candy cane stripes – many varieties that neither they, nor diners at Greens had seen or tasted before. They went to a farm near Fairfield and picked their own vegetables and over time, forged relationships with other small, organic farmers. No one talked about farm-to-table or local and seasonal. “It was just what we were doing,” Madison writes.

And in a line that to me encapsulates Madison and her love for vegetables, she says: “They just cooked themselves, basically, and I tried not to get in the way.”

American academic and author (her books include Unsavory Truth: How Food Companies Skew the Science of What We Eat) Marion Nestle remembers eating at Greens. “What was brilliant about Greens was that the food was so good. You didn’t have to be a vegetarian to want to go there. It was almost impossible to get into.”

The Greens Cook Book followed. The late food writer Marion Cunningham wrote in the foreword: “I found this book to be fine reading, a comfortable bedside book that has at times, the feeling of poetry.” And there is a feeling of poetry in Madison’s writing – a thoughtfulness and care – that she takes with her cooking too. Elissa Altman echoes these thoughts. “I’ve seen her (Madison) pull dusty root vegetables out of her New Mexico garden and treat them with the exact same sort of tenderness a poet like her friend Jane Hirshfield might accord words. There is no difference, I suspect.”

Madison stayed at Greens for about three years. After she left the Zen Centre, she cooked in Italy, moved to Arizona and finally settled in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she lives with her husband the artist Patrick McFarlin (they co-wrote and he illustrated the book What We Eat When We Eat Alone – a great read on the pleasures of solo dining).

Along the way she’s written more books: Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone – a comprehensive primer for vegetarian cooking with a whopping 1,400 recipes; Local Flavors: Cooking and Eating from America’s Farmers Markets, which champions small farmers and growers. When she wrote Local Flavors, there were only around 3,000 farmers markets in the US – today the number is closer to 9,000. Madison has done much to help nourish the growth in local markets and captures the joy of buying direct from a grower. “I know of absolutely no one who goes to the farmers’ market with a list and comes home with just what’s on it, or who doesn’t spend every penny she bought.”

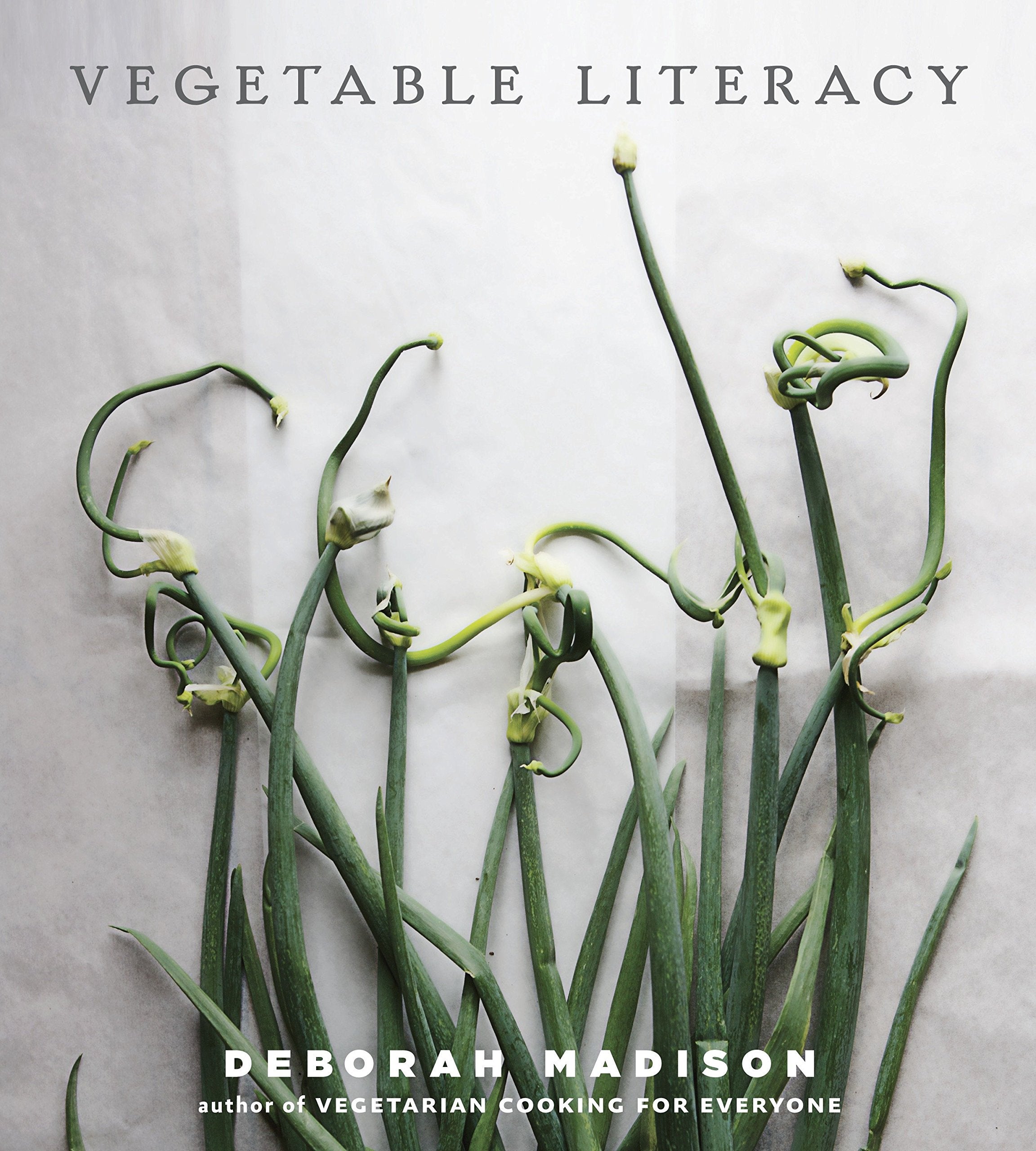

But if I had to choose my desert island read, it would be Vegetable Literacy. The premise is deceptively simple: a deep dive into 12 plant species that include the vegetables we eat most. So the carrot family, for example, is home not only to carrots but also celery, celery root (celeriac), parsnips as well as a whole host of herbs like angelica, caraway chervil, cilantro (coriander), cumin, dill and lovage.

Once we know who’s in the family, she writes, we can see the connections. “We can see how we might substitute related vegetables when cooking, or how all the umbellifer herbs, including cilantro, parsley, and chervil, flatter umbellifer vegetables, such as carrots and fennel.” She includes notes on her favourite varieties like Paris market carrots – “stubby little spheres” – or Dragon, Atomic Red and Cosmic Purple – glorious names for purple carrots with orange flesh.

It’s the kind of a rabbit-hole of a project that many food writers could fall into but few would emerge from. Reading it, I’m struck by how Madison is always in charge of the material, whether it’s a suggestion on how to use carrot tops, sharing a bit of kitchen wisdom (scrub, don’t peel carrots) or a note on good ‘companions’ for each vegetable. And then there are the 300 recipes like her carrot soup with tangled collard greens in coconut butter and dukkah, that urge you to view something as ‘common’ as a carrot in a fresh light.

And she does all of this without ever losing her passion for the plants themselves and the spark of wonder at how amazing they are. “Because I overlooked some carrots in my garden one fall, I was rewarded with a display of large, lacy flowers the following summer,” she writes. Rather than yank the plant out and toss it onto the compost heap, Madison pauses. “A halo of fine, feathery greens framed each flower, and the plush surface of the blossom easily supported an insect’s ramblings, like the iridescent blue wasp I watched one day making his way from edge to edge.”

I think back to my local vegan butcher and their “pastrami”. Am I tempted to try it? Absolutely, if for no other reason than to see if it bears any relation to the countless pastrami sandwiches I’ve eaten joyfully in New York City delis. Sadly, the vegan butcher’s website says they’re closed until 4 February so I go online instead looking for recipes. Can they come anywhere near the pastrami sandwiches I’ve eaten – slices of rye bread that serve as bookends for stacks of sliced pastrami (brisket, trimmed of fat, lovingly rubbed with salt and seasoning, cured, smoked and cooked).

There is a version made from celeriac (the other popular option was seitan – wheat gluten which mimics the flavour of meat). You cook the peeled, whole celeriac with aromatics – leek, fennel, onions and garlic with vegetarian stock, add liquid smoke and other ingredients. Slice the cooked beetroot thinly on a mandolin and then marinade to give it pastrami’s characteristic pink hue. Assemble the pastrami sandwich with vegan mayonnaise and vegan cheese and the requisite pickles.

It doesn’t sound bad (minus the vegan mayo and cheese). But it doesn’t sound like pastrami. Instead, I flick through Madison’s Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone where there are nine recipes alone featuring celeriac including a salad with slivers of crisp apple as well as several gratins, including an artichoke, celery root, and potato gratin that catches my eye. I settle on a vegan dish of braised celery root with garlic croutons and pair it with a simple green salad dressed with a mustardy vinaigrette.

I take a bite. It definitely doesn’t taste like pastrami. It tastes like what it is, which is what I love.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments