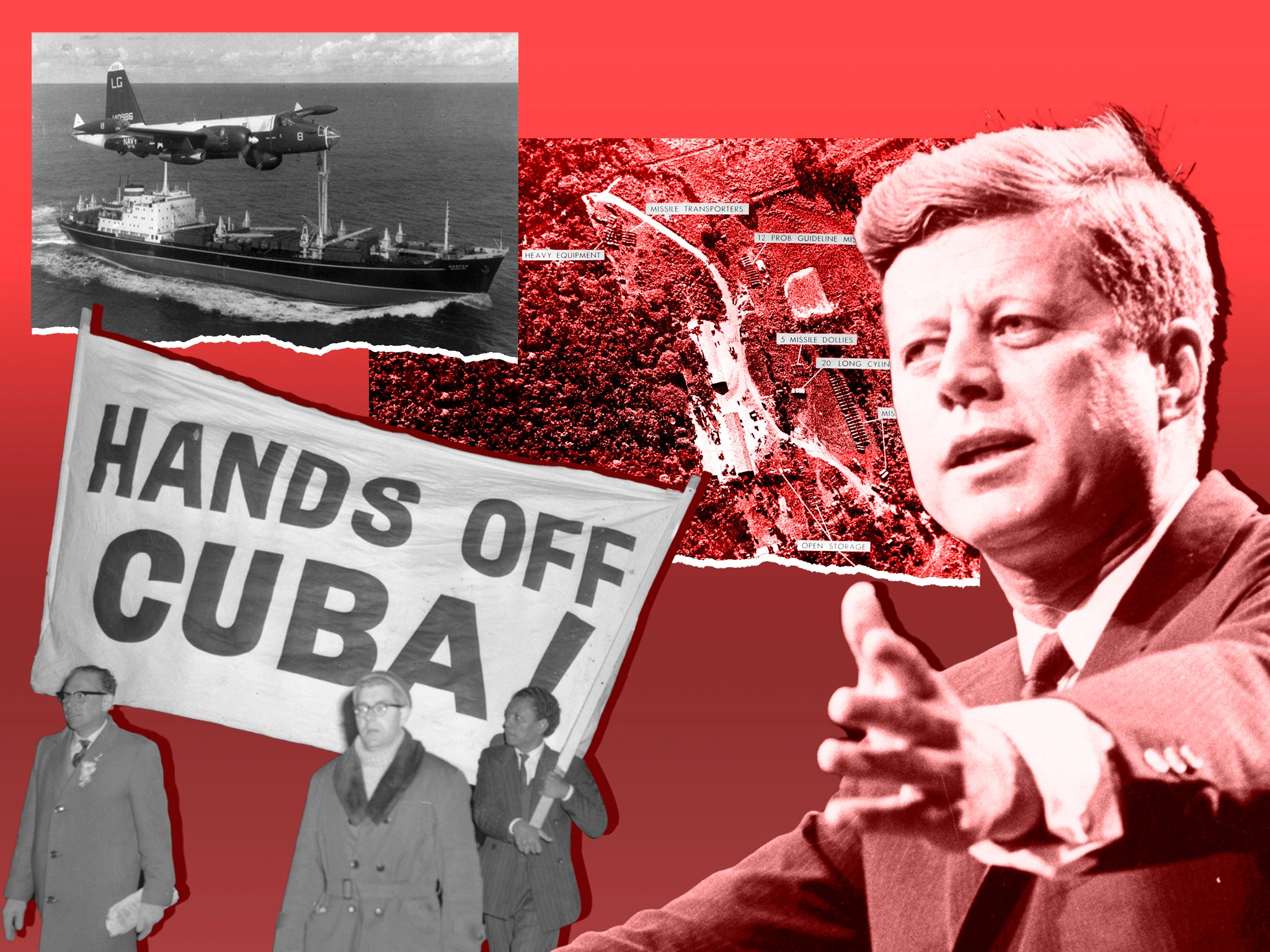

On the brink of disaster: What can we learn from the Cuban missile crisis?

Sixty years after one of the biggest flashpoints of the Cold War, Mick O’Hare revisits the crisis and explores why it happened and what we can learn about political brinksmanship

On 27 February this year, shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine, Vladimir Putin placed the country’s nuclear deterrent on high alert. He said it was in response to Nato’s “unacceptable aggression” and that Western nations might suffer “consequences never seen before”. He repeated the threat when he mobilised reservists on 21 September. Putin’s brinkmanship is on a level not witnessed since the Cold War. Political and military strategists are warning that the world is nearer to nuclear annihilation than at any point since 1962.

Sixty years ago this month, what has become known as the Cuban missile crisis began. The world’s two nuclear superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States, faced off across the Straits of Florida and the world, to resurrect a cliche, held its breath. Although Putin has also said a nuclear war is not winnable, the sabre rattling continues with veiled – and no so veiled – threats. Putin’s motive, presumably, is to make Nato think twice about its level of involvement in the Ukraine war.

But back in 1962, the motives of Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev were more opaque. Why did the Soviet Union decide to place missiles on an island so close to the US mainland? Khrushchev, an intelligent politician, must have known that the American response would be angry and prodigious which is why, initially, he went to great lengths to conceal the missiles’ deployment. Equally pertinent, given the current situation in eastern Europe, how did the two superpowers extricate themselves from the resulting showdown with no loss of face?

And lastly, while the avoidance of conflict over Cuba has always been seen as a triumph for US president John F Kennedy, was that, with the benefit of 60 years of hindsight, really the case? Does it depend on who penned the narrative?

On 14 October of that year, US Air Force Major Richard Heyser was making a high-altitude pass over the island of Cuba in a U-2 surveillance aircraft. Cuba had become a socialist nation aligned with the Soviet Union and dependent on the superpower for military and economic aid following Fidel Castro’s ousting of US-backed military dictator General Fulgencio Batista in 1959. Unlike most Soviet satellite states, however, this one was a mere 90 nautical miles from the US coastline. The Cold War had arrived on America’s doorstep.

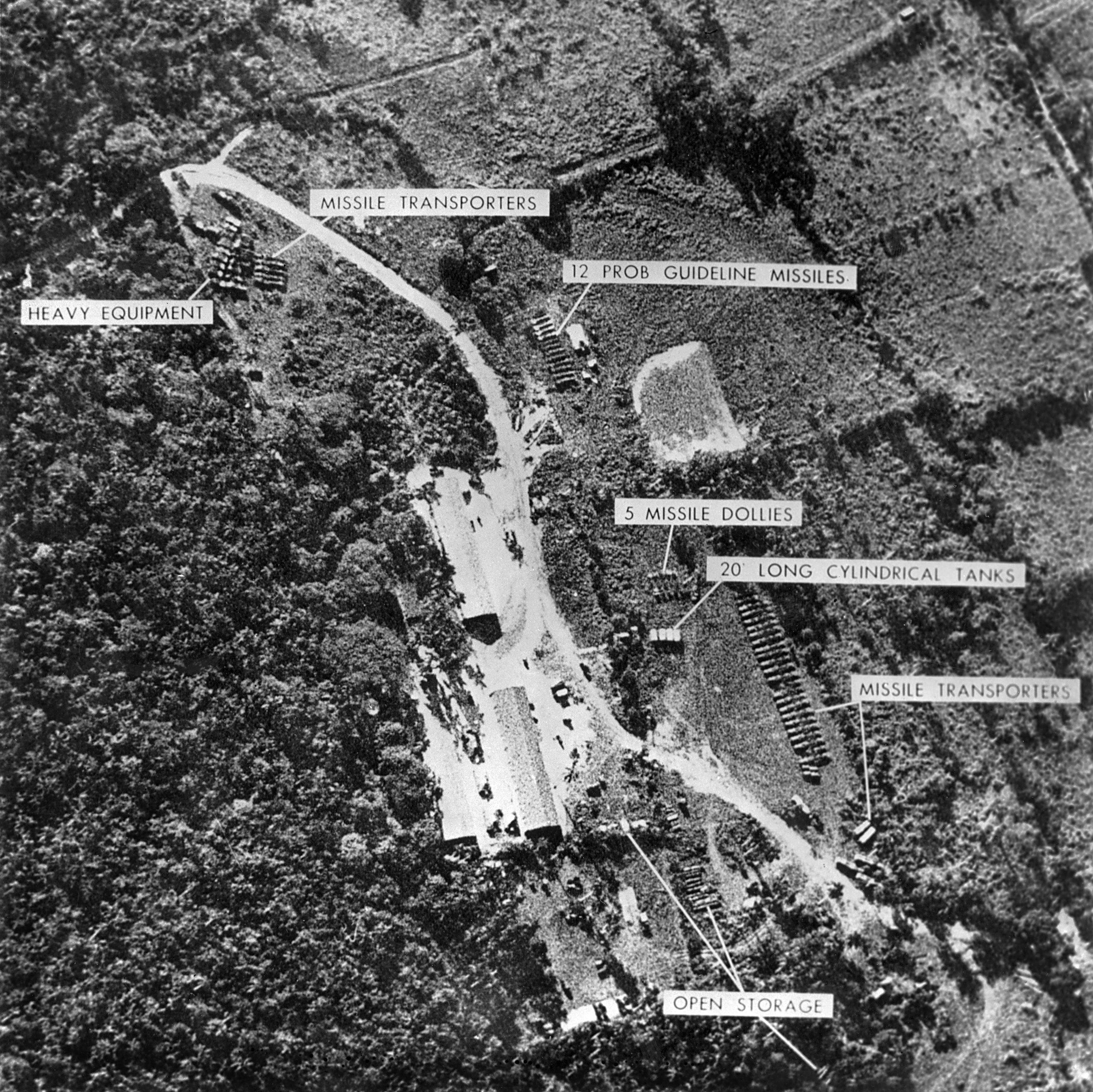

Wary that the Soviet Union was sending military hardware to Cuba, the US had been overflying the island since the summer. When the photographs from Major Heyser’s U-2 were developed it was clear the Soviet Union was not just supplying guns, ships and planes to the Cubans, they were also constructing facilities to assemble and launch nuclear missiles. Once the missiles were operational the fulcrum, both politically and militarily, of the Cold War would shift significantly. Kennedy immediately convened an Executive Committee of the National Security Council (Excomm).

Strategists and historians have puzzled over the rationale. Khrushchev must have realised that the US would respond to such a destabilisation of the Cold War order. And at some point, once the missiles were operational, the Soviet Union would have to reveal they were there, for without the threat that they might be used they served no purpose. The whole basis of Mutually Assured Destruction was that both sides knew the other’s capability.

Any number of theories abound. Was Khrushchev calling Kennedy’s bluff? In 1961 a group of Cuban exiles opposed to Castro’s revolution and covertly backed by the CIA, landed at the Bay of Pigs on Cuba’s south coast intent on overthrowing Castro. It was a failure, Castro’s position was enhanced and the Kennedy administration publicly embarrassed.

Khrushchev had long felt uneasy about US nuclear weapons in western Europe and the American deployment of missiles to Turkey, just over the Black Sea from Crimea, in 1961 had finally forced his hand. An “intolerable provocation,” he announced.

The story goes that Khrushchev was walking along the beach at Varna in Bulgaria and decided he too could place missiles in the enemy’s backyard. “Let’s throw a hedgehog into Uncle Sam’s pants,” he was reputed to have said. To level the playing field he would send Soviet missiles to Cuba. Archive evidence suggests Khrushchev gambled on Kennedy’s response being indecisive. His advisers decided Kennedy was pusillanimous; “too intelligent and therefore too weak”, was one assessment. Kennedy, said Khrushchev, “would make a fuss, make more of a fuss, and then agree.” The Soviets were emboldened, they expected the US president to accept the weapons as a fait accompli.

But maybe Khrushchev had other motives? At the time, Kennedy and Excomm surmised that Khrushchev was attempting to bring about a resolution of the Cold War conflict in Germany. Berlin had been divided between the four victorious Allied powers following the Second World War. This had left West Berlin, controlled by the US, Britain and France, deep inside Soviet-backed East German territory. The Soviets considered this a threat to their hegemony in eastern Europe.

Whatever Khrushchev’s motives, his actions deliberately or inadvertently took the planet closer to nuclear annihilation than it had ever been

Blockading West Berlin in the late 1940s had proved unsuccessful, so Khrushchev was looking at other options. He had already ordered the building of the Berlin Wall to isolate the west of the city. Maybe his strategy was to use the missiles in Cuba as a bargaining tool – the Soviet Union would remove them if the Western allies left Berlin. “It’s an argument with merit,” says former US diplomat and Cold War historian Philip Zelikow. “West Berlin had far more strategic importance to Khrushchev than Cuba, so he would see the trade-off as a win.” This was an argument that was dismissed in the aftermath of the crisis because west Berlin’s status remained unaltered, until it was resurrected in 1999 by Zelikow in his book Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis co-written with Graham Allison. They contended that the Soviet focus was on its own backyard – Berlin was more important than Havana, Castro more expendable than East Germany.

Khrushchev had also been taking note of the “missile gap”. In 1962 the Soviet Union had very few missiles capable of reaching the United States (excluding Alaska). Meanwhile, the US had around 200 long-range weapons. Not only that, the Soviet missiles were less accurate and less reliable. Putting them in Cuba meant more chance of a successful strike.

Carl Warner, principal curator and historian of the Cold War at the Imperial War Museum, says: “There’s an element of truth in all these theories. Statecraft is about balancing competing and sometimes conflicting priorities. Is it safe to gamble? The Bay of Pigs showed Cuba needed defending, but also showed Kennedy’s apparent weaknesses. When Khrushchev first met Kennedy, he thought Kennedy had something of a glass jaw. Kennedy, meanwhile, thought Khrushchev would be difficult to deal with.” On such first perceptions are decisions formulated. Warner goes on: “So Khrushchev probably reckoned it was worth the gamble of putting missiles there. It would even up the odds and possibly create a bargaining chip.”

So was it ever about Berlin as the Americans believed? “Partially,” says Warner. “But it would be wrong to see any of these theories as the sole catalyst.”

Whatever Khrushchev’s motives, his actions deliberately or inadvertently took the planet closer to nuclear annihilation than it had ever been. Throughout late October 1962 international diplomacy was tested to its limits, and – for once – prevailed. But how? Did the two superpowers step back from the brink in a selfish (or even selfless) act of self-preservation? Or were other issues in play? Was it a game of diplomatic chess in which there was never going to be a negative outcome, and instead was all about what each could extract from the other?

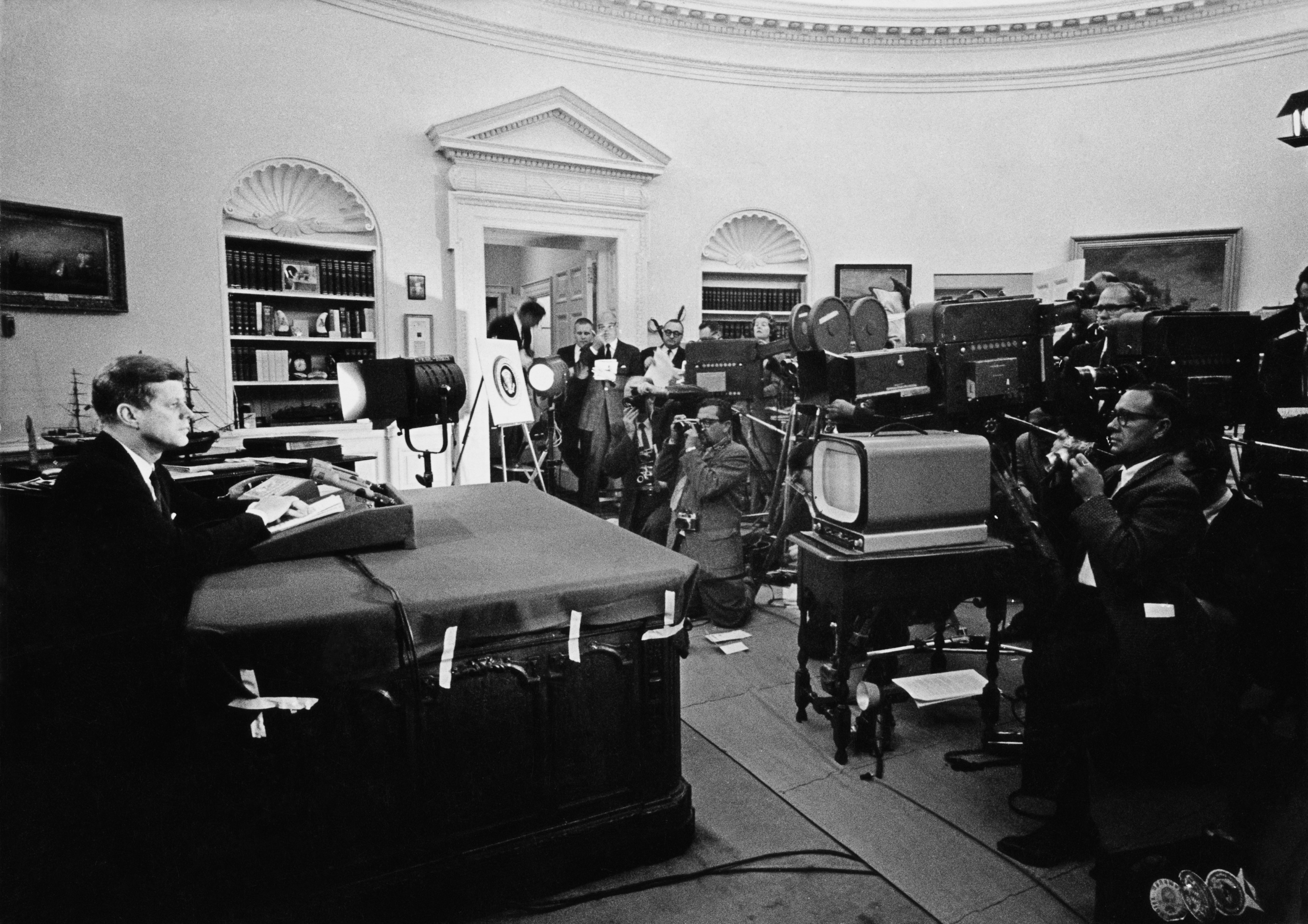

Kennedy’s initial response to the missiles’ discovery was to inform the American people in a televised address on 22 October. He made clear the US would use military force to neutralise the threat and he would deploy the US Navy to impose a blockade of Cuba. Humanitarian supplies only would be allowed through. Kennedy termed it “a quarantine”, Khrushchev called it “piracy”.

There has been considerable argument over whether the missiles’ presence in Cuba really did threaten the US any more than missiles based elsewhere. The political challenge to Kennedy and Excomm, though, was how to achieve the missiles’ removal without actually using the military and the attendant possibility of nuclear war. Kennedy was wise to the fact that Khrushchev had a point about US missiles in Turkey, he did not want to seem hypocritical, but nor did the calculating Khrushchev. Both knew their actions in the coming days would reflect on the morality of their two conflicting ideologies.

Largely unbeknown to Excomm, indeed pretty much the rest of the world, the president and his closest confidant and brother, US attorney general Robert Kennedy, had opened backdoor negotiations with Moscow via Soviet ambassador Dobrynin. Dobrynin arranged a meeting at the White House on 18 October – before Kennedy addressed the American public – between Kennedy and Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet foreign minister who had been in New York to attend the United Nations General Assembly.

Both sides were on full nuclear alert. People missed work, some kept their children home from school. The missiles in Cuba were now operational and Kennedy primed Excomm for an invasion

At that point Kennedy did not reveal to either Gromyko or Dobrynin that he knew of the missiles but made it clear the US would not be a threat to the Cuban regime. Gromyko insisted that the Soviet Union’s military aid to Cuba was defensive and unthreatening. Both Gromyko and Kennedy departed the meeting feeling that the other was a person ready to talk. It was a crucial turning point. Kennedy deduced the missiles would not be fired unless the US struck first. It was a calculated assessment of the meeting and it was probably correct. It meant he could oppose those in his military who wanted an assault on Cuba.

Just before he addressed the American people, Kennedy revealed to Dobrynin that he knew about the missiles. Apparently, Dobrynin sat in his office at the Soviet embassy for 15 minutes before informing the Kremlin. Khrushchev was furious. “If they attack, we respond,” he said. But it was bluster, more in response to being found out than a genuine threat of outright war. It was at this point that Kennedy’s entreaties to Gromyko came into play. Gromyko relayed to Khrushchev his belief Kennedy would not attack first.

On 24 October at 10.25am US intelligence reported to Kennedy that Soviet ships appeared to have stopped short of the line of naval blockade. “I think the other guy just blinked,” said Secretary of State Dean Rusk. There was relief but the missiles already in Cuba were, of course, still there although the Soviet Union was continuing to deny their presence at the UN Security Council in New York. Khrushchev needed a way out.

As did Kennedy. His advisors estimated that to invade Cuba would mean 18,500 US casualties. He could not countenance that, especially with mid-term elections looming. It required more back-door intervention. This time it came from the Soviet side. On 26 October ABC television’s diplomatic correspondent John Scali was invited to meet Aleksandr Fomin, a KGB agent using an alias who worked at the Soviet embassy, for lunch at the Occidental Restaurant next door to Washington’s Willard Hotel. Although it was not a formal approach from the Kremlin it appeared to be a feeler. Fomin said that if the US promised not to invade Cuba the missiles would be removed. Scali immediately told Rusk who told the president.

Later that evening a letter arrived from the Kremlin stating the same, adding the words: “We and you ought not to pull on the end of the rope in which we have tied the knot of war.” Robert Kennedy described its contents as “long and emotional” and the US believed it was dictated by Khrushchev himself. In the early hours of the next morning, Robert Kennedy met Dobrynin once more. This time Dobrynin mentioned US missiles in Turkey. The president’s brother, with the president’s approval, suggested that maybe a deal could be done. Kennedy had been skilful, but at the last minute Khrushchev had played a winning card. He too now had a climb-down position.

“Intermediaries are vital,” points out Warner. “The other side needs to know that what they are hearing comes from the top, and that the information is genuine. Because what was being said in the back channels was different to what was being said in public, an honest broker was required – Dobrynin could be trusted. Speed is important too, how quickly does the information reach those who need it? For example, when the Americans received the two different letters some on the American side believed it was evidence that Khrushchev had been overthrown in a coup. It wasn’t so, as Dobrynin confirmed. So the ability to trust was vital. Dobrynin was part of that, as was Bobby Kennedy.”

Warner is referring to a second letter that arrived from the Kremlin on 27 October, the day after the first letter, this time mentioning Turkish missiles as the price for removing the Cuban missiles. Many Excomm members were furious. The Kennedys were aware that only the night before they had suggested such a plan but they had kept Excomm in the dark. “Any rational person will regard [the Soviet demand] as not unreasonable,” President Kennedy told his committee. Against Excomm’s judgement, he said that removing the missiles in Turkey was the price to be paid to avoid nuclear war.

And then came a flashpoint. An American reconnaissance plane was shot down over Cuba and its pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson Jr, killed. How would both sides react? US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara wrote that he believed 27 October would be the last Saturday he would ever see. But although US bombers remained constantly airborne the Soviet Air Force did not respond in kind. Soviet naval ships too were altering their course. Maybe a window of opportunity had opened.

Early that evening delegates of both sides, with the approval of Kennedy and Khrushchev – and rumoured once more to have included Scali and Fomin – met secretly at the Attorney General’s office in Washington DC. It was Cold War diplomacy at its most clandestine, the stuff of movies. The US demanded to know why two letters had arrived from the Kremlin. The Soviets said it had been a communications error. Neither knew if the other was lying. Decisions had to be taken on trust, with many fingers crossed, but terms were eventually thrashed out, although again Excomm members were not party to the deal.

At 8pm the US responded to the Kremlin’s first letter guaranteeing no invasion of Cuba if the Soviet Union withdrew its missiles. It made no mention of a quid pro quo over Turkey – the US did not want to look like it had capitulated in the face of provocation. But would Khrushchev accept? Would it look publicly like he had backed down? There was only hope, not expectation.

The conflict didn’t escalate and instead resulted in an acknowledgement that the way international diplomacy was conducted was inadequate for the nuclear age

The following morning Radio Moscow announced the Cuban missiles would be dismantled. Voice of America announced the blockade would end when the missiles were gone and that its invasion force would also be standing down. Fidel Castro announced that Khrushchev was “a son of a bitch, bastard, asshole,” for making him look like a Kremlin puppet. And nobody told Turkey anything until the missiles began to be removed in 1963 using the excuse they had become obsolete.

That same year a communications hotline was installed between the White House and the Kremlin. The risk of misinterpretation had become too great. The line still exists and is tested every day.

History seemingly records that Kennedy was the winner. His demands were met and he “saved the world”. He was indeed a skilful politician but it would be remiss to ignore the role of Khrushchev. His politburo, too, knew that the missiles in Turkey would be removed even if the wider world did not although he would still fall from power two years later, notably without mentioning in his defence the Turkey concessions that he helped force upon Kennedy. “He kept quiet because, reading between the lines, he knew the deal was fragile,” suggests Warner. “If he made a public show of it, it might fall through.” Similarly, Kennedy told Scali not to mention Turkey in his TV reports. He too realised that if word leaked out, it might look as though the US had backed down which could scupper the deal.

“In a sense, both sides won,” says Warner. “This kind of confrontation was, with hindsight, necessary to implement the changes required to avoid similar conflict... it was no way to solve an international crisis. It had to be done better in the future. So in many ways it was a relief that it happened. It tested both sides and fortuitously both had reasonable actors with vision. It was a win for rationality.”

The myth has arisen that Kennedy gave nothing away, yet he did. But he needed secrecy knowing that it would damage his standing and lead Nato allies, of which Turkey was one, to question his commitment. Both men walked together to the brink, looked over and, holding hands, stepped back. Neither wanted war.

“And that was the key,” says Warner. “Both men were reasoned and sensible.”

“That layer of civilian government showed its worth during the Cuban missile crisis,” adds Warner. “We’ll never know how near we came to nuclear war in 1962 but it’s fair to say we came closer than at any other point.”

So is there a glimmer of hope when there are suggestions we could be as near to nuclear war now as at any time since 1962? Michael Dobbs, author of One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the brink of nuclear war, has this to say of that critical Cold War confrontation. “The crisis remains the best-documented study of presidential decision-making at a time of supreme national danger. It offers policymakers unique insights. To prevent such a moment ever happening again – and we can – we need to continue to study the Cuban missile crisis.” On a slightly more disturbing note, he adds that had other leaders been in charge in October 1962 “the outcome could have been very different”.

The lessons of the Cuban missile crisis are many and varied. And taking a path of least resistance when it is offered is one of them. How diligent a student is Putin?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments