The life and death decision of choosing who to vaccinate

In Northern Ireland, vaccine shortages have forced GPs to choose between inoculating the most vulnerable in society or the most important in fighting back against the virus, writes Olivia Fletcher

On 2 December, Dr Alan Stout had to make the biggest decision of his 20-year career as a doctor: choosing who should get their Covid-19 vaccinations in Northern Ireland.

The Belfast GP, who had been given the near-impossible job of leading a team to negotiate the terms of a rollout plan for Northern Ireland with its Department of Health, had been told how many doses of the Pfizer vaccine he had been allocated to treat 195,000 people in the first phase of the plan.

It was just 80,000.

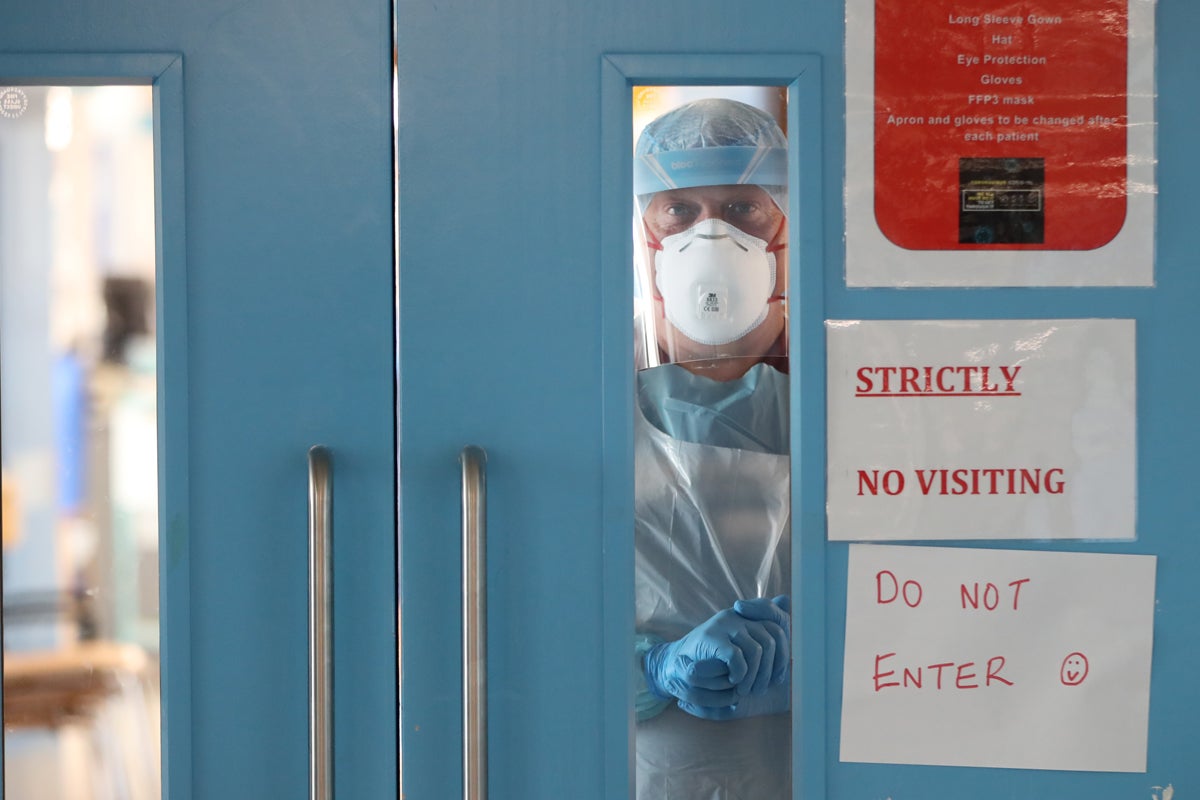

Needing two-and-a-half times as many to give just one dose each to care home resident and staff member, healthcare workers, and those over the age of 80, Stout and his team were faced with a stark choice: to prioritise the NHS staff who could keep tens of thousands of people throughout Northern Ireland alive, or the elderly, who are most likely to die if they contract Covid-19.

Stout, whose day-to-day job is at Greenway Practice in suburban east Belfast, was about to make a gutsy choice.

The over-80s were crying out to be protected. But so was the NHS.

“Without a fit and healthy population of healthcare workers, we cannot staff practices, emergency departments, intensive care units, and nursing homes,” Stout says. “This then creates an incredibly difficult environment which effectively collapses the NHS.”

So, by 21 January, 81,000, or 85 per cent of healthcare and domiciliary care workers, had received their first dose of the vaccine, and 92 per cent of care home residents and staff had received theirs.

Northern Ireland had hit a target that no other UK nation had achieved, thanks to Stout and his colleagues. Getting care home residents and staff vaccinated was a “top priority” in Northern Ireland, Stout says. And it showed. Northern Ireland was “way ahead” of the rest of the UK when it came to vaccinating those in care homes, he added. By 28 January, it had vaccinated 100 per cent of them.

But it was lagging behind elsewhere. On 21 January, only 36,419 of Northern Ireland’s 72,000 over-80s had been vaccinated – or 55 per cent.

By then, over-80s were continuing to die at a disproportionate rate. On 21 January, of the 1,692 people who had died from coronavirus, 1,049 were over 80. Comparatively, less than 10 healthcare workers have died.

How many of those over-80s would still be alive had Stout and his colleagues on the negotiating team been given enough doses to vaccinate more than 55 per cent of Northern Ireland’s oldest citizens in December is impossible to judge.

But a “conscious decision” had to be made, Stout acknowledged. With a short supply of Pfizer vaccines, there was only one choice. To protect those who needed saving or to protect those who do the saving.

And so, it was decided that, for the last 10 days of December, the over-80s in Northern Ireland would not receive vaccinations, and healthcare workers would receive theirs.

Stout, who chairs the Northern Ireland General Practitioners Committee, was joined by Dr Laurence Dorman, chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, and the head of general medical services on the Health and Social Care Board, Dr Margaret O’Brien, along with her two lead medical advisors, in negotiating the terms of the rollout with Patricia Donnelly, the head of the Covid-19 Vaccine Programme.

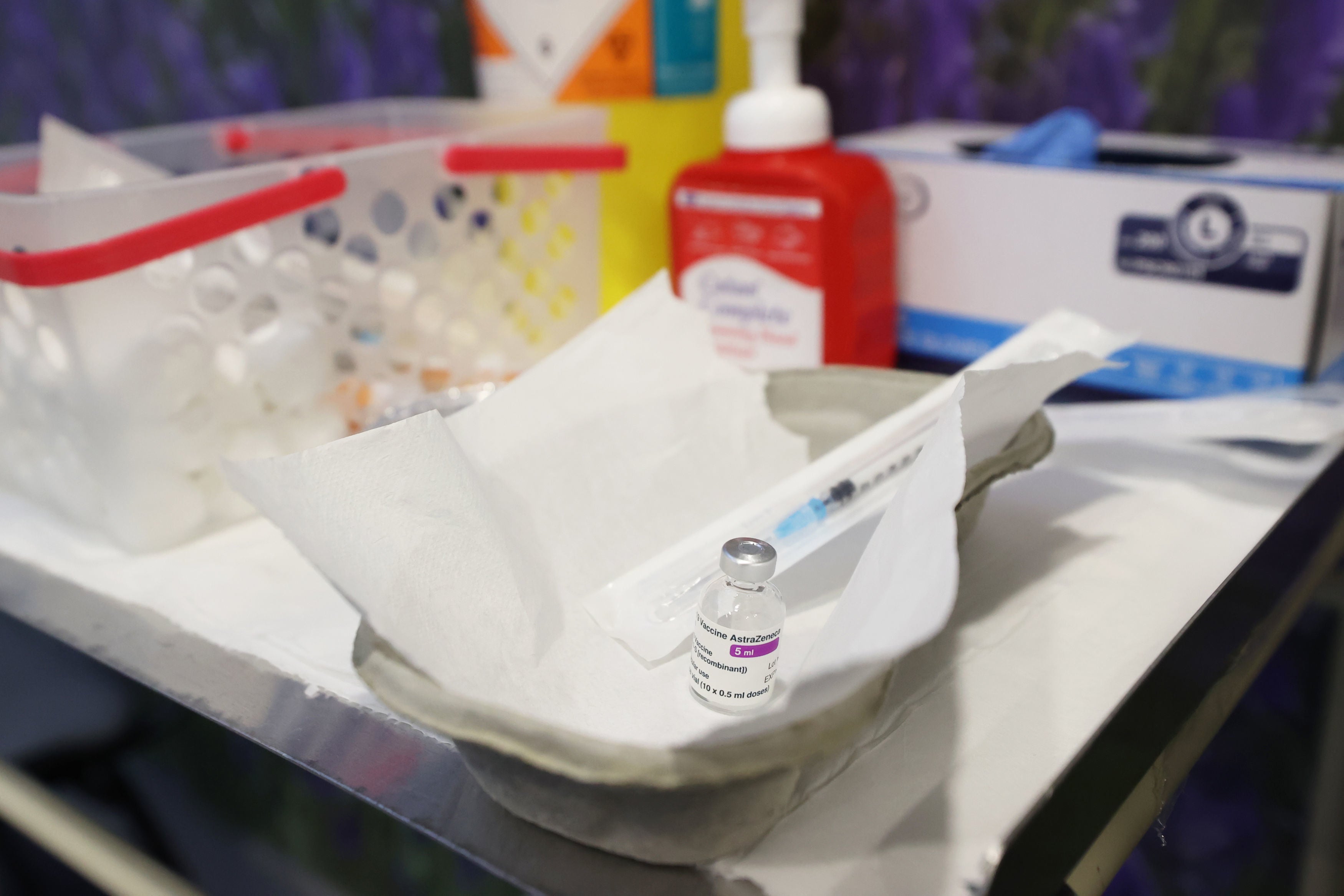

Their preparations had been meticulous. Seven makeshift vaccination centres popped up across Northern Ireland to administer the Pfizer vaccine, and all 331 medical practices signed up to give patients the AstraZeneca vaccine. More than 1,000 additional staff were signed up to assist in its delivery.

All they needed for a full rollout of vaccinations for the over-80s was more vaccines. To Stout’s relief, on 30 December the AstraZeneca vaccine was approved and, immediately after, 50,000 doses of it were delivered from England.

“Supply is key now,” says Stout, adding that “the quicker we get the vaccine, the more people will get it sooner, and absolutely the more lives will be saved”.

Without a fit and healthy population of healthcare workers, we cannot staff practices, emergency departments, intensive care units and nursing homes. This then creates an incredibly difficult environment which effectively collapses the NHS

Stout and his team decided to dedicate the AstraZeneca vaccinations received to the over-80s because it is better suited to mass-vaccinating whole communities. It’s easier to administer and, unlike the Pfizer vaccine, has a long shelf life that doesn’t require deep freezing.

So, an army of healthcare workers assembled, poised to inject first doses into the arms of the over-80s from 4 January.

But the same problem arose. With only 50,000 doses of AstraZeneca, and more than 72,000 over-80s in Northern Ireland, there wasn’t enough supply.

Joe and Mary Wallace, aged 84 and 82, had been due to receive their vaccinations on 14 January, but were disappointed when, just three days earlier, they received a phone call from Notting Hill medical practice in leafy north Belfast telling them that their vaccinations had been cancelled.

Their vaccination centre had run out of doses. They were left feeling “nervous and a little disheartened”.

The happily married couple of 59 years have enjoyed sharing moments on long walks since Joe retired as a retail manager in 2000. But their favourite pastime is seeing their two children and nine grandchildren, who they’ve been isolated from since the autumn.

“It is stressful for us waiting all the time,” says Joe. “We would just like to have the vaccine so that perhaps we can see our family.”

Twenty-one-year-old Abby Wallace said her grandparents “have come so far now”, adding: “To see either of them get ill at this stage would be heart-breaking.”

On 18 January, some 32,000 more AstraZeneca doses were delivered. And regular deliveries of the vaccine will commence shortly, Stout tells The Independent.

Now there were enough doses to vaccinate all over-80s.

But, as the final phase one rollout began, deaths continued to rise.

Three weeks ago Northern Ireland was experiencing its highest weekly death toll since the start of the pandemic. And on 25 January, the nation recorded a total of 1,747 Covid-19 deaths, of which 1,080 were over the age of 80.

Stout’s team faced a race against the virus.

By 31 January, remarkably, 100 per cent of the over-80s had been vaccinated, “bar a very small amount of exceptions”, which included those who refused the vaccine. This put Northern Ireland firmly ahead of the rest of the UK. In England, on the same day, only 90 per cent of over-80s had received vaccinations.

It meant, too, that on 29 January, Joe and Mary finally received their first doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, even despite the 10-day delay that was called for in December.

The decision to batch-vaccinate healthcare workers first meant that Joe and Mary, along with every other 80-plus-year-old in Northern Ireland, has now received their vaccination, proportionately ahead of their neighbours across the Irish Sea.

But without a date booked in for their second doses, and the majority of Northern Ireland still not vaccinated, the married couple will have to wait months to safely go grocery shopping, take their long walks without fear of catching the virus, or hug their grandchildren. And those months won’t be easy.

Some over-80s are “really nervous that they don’t have two years of their life to waste” isolating from their loved ones and missing milestones, Charlotte Lynch, policy manager at Age UK, says.

Lynch surveyed 369 older people in October last year for her research on the physical and mental impact of Covid-19 on the elderly. “Older people,” she says, “are really struggling to cope.” They have “lost confidence,” she adds, in doing things that they’ve done for most of their lives, such as feeding themselves and shopping for fresh food.

Since the first lockdown, the number of people ordering their shopping online has soared. Other aspects of life have become digital too. Some GPs are now encouraging Zoom appointments, for instance, instead of face-to-face.

This new way of living, exposed by Covid-19, illuminates that in communities across the UK, there is a gaping age divide between those who do and don’t use the internet. And this is making life extremely difficult for older people as they try to survive the pandemic.

In March last year, a separate Age UK report found that, out of 134 older people interviewed, over half didn’t have a device on which they could access the internet. Of those who had used the internet in the past three months, 49 per cent of them admitted to finding it difficult to keep up with ever-changing technology. The report also highlighted that, according to the Office for National Statistics, 3.9 million people aged 65-plus in the UK do not use the internet.

Imagine suddenly being asked to ‘book a slot’ two to three weeks in advance of buying a pound of potatoes and a pork chop. By a person called Karina, who wants to ‘chat’ without actually speaking a word

And nobody understands what implications this has, in real terms, more than Beckie Lawless.

It was 9.49am on Friday 3 April last year that Lawless, managing director of Osolocal2u, one of the UK’s fastest-growing home delivery food companies, discovered just how vast the age disparity is between those who do and don’t use the internet.

As England entered the 12th day of its first lockdown, Lawless received her most anxious call for help yet.

“We’d had our busiest 24 hours ever and were exhausted” she says. “All 40 of my refrigerated delivery vehicles were already on the road that morning, when an email came in from a GP in northwest London.”

One of the GPs patients, a 96-year-old lady, was totally out of food.

“She is completely isolated,” the doctor’s message to Lawless said. “She desperately needs any food that's easy to eat.”

“Worst of all,” Lawless adds, “none of the big-name online food companies could offer her a delivery slot within the next three weeks.”

Lawless rushed her son, Harry, to the elderly woman’s front door. He arrived clutching a large box of bread, milk, jams, ready-to-eat foods and plenty of fruit and vegetables. The lady who opened the door, nearly starving, had become so convinced she would never get anything to eat, she asked, “Have you come to fix my boiler?”

“No one should be surprised at how psychologically disturbed Britain’s old age pensioners have become,” says Lawless.

“They have lived, for more than half a century, securely in a world in which they went shopping three, four and more times a week. In places where they could see, touch, feel and even smell goods before deciding which fresh fruit and vegetables to buy.

“Imagine suddenly being asked to ‘book a slot’ two to three weeks in advance of buying a pound of potatoes and a pork chop. By a person called Karina, who wants to ‘chat’ without actually speaking a word.”

For three decades, Lawless has dealt with hundreds of professional chefs. “I am now being kept on my toes by our new, but older, generation of customers. And we really are trying very hard to help them make the choices they so love to make, by giving them more information about our products than they probably need, and certainly don’t get from elsewhere.”

Lawless even has a resident recipe writer, Liberty Fennell. She writes in-season recipes, so older people know how to cook all kinds of foods, when they are freshest, and available at the best price.

Older people are able to call Lawless’s how-to-order-online hotline at 0208 988 7066, too.

The online industry may even be losing money by believing that talking to its oldest customers is expensive, Lawless contends. “Many online retailers don’t even want to give their customers their telephone numbers or their addresses. They shun any contact because they think that engaging with them is just a cost.”

While Lawless usually supplies hundreds of eateries with the finest ingredients in London and across the south coast, from Bournemouth to Hastings, she is now tasking herself with feeding some of the most elderly and vulnerable, and those in care homes, who will still endure months of hardship as arms are jabbed and the divide between those who do and don’t use the internet continues.

This divide makes Stout’s achievement all the more welcoming to over-80s in Northern Ireland.

And it looks certain that the nation will continue racing ahead of the rest of the UK too. Stout tells The Independent that 65 to 69-year-olds are being vaccinated sooner than planned, via the seven vaccination centres that have sped up the nation’s rollout plan.

His decision-making, faced with all the odds, has meant that older people in Northern Ireland may look forward to their second doses and getting their lives back sooner.

The GP would usually enjoy playing golf in his spare time. But he hasn’t had much of that recently. However, “I do still try to do some gardening – particularly cutting things down which helps release stress”, he says.

If a medical Hall of Fame existed, Dr Stout would surely be in it. Stout describes the past few months as “the hardest time that any of us involved in healthcare have ever been through”. But he knows there are more tough months to come.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments