I dealt with the first major outbreak of Covid in the UK. This is what it’s like one year on

Laurie Churchman was among the first reporters to face the coronavirus pandemic as it broke out in Brighton last February. He returns to the streets to find suffering, strength and a strange sense of hope

The voice on the other end of the line sounded frightened. It belonged to a nurse. She was in shock. “I’m so scared,” she said. She had been treating a suspected coronavirus patient at a Brighton hospital before her bosses bundled her into a cab and told her to go home and stay indoors. The driver hadn’t been wearing a mask. She was advised to get her children out of the house, and held back tears as she described being separated from her family.

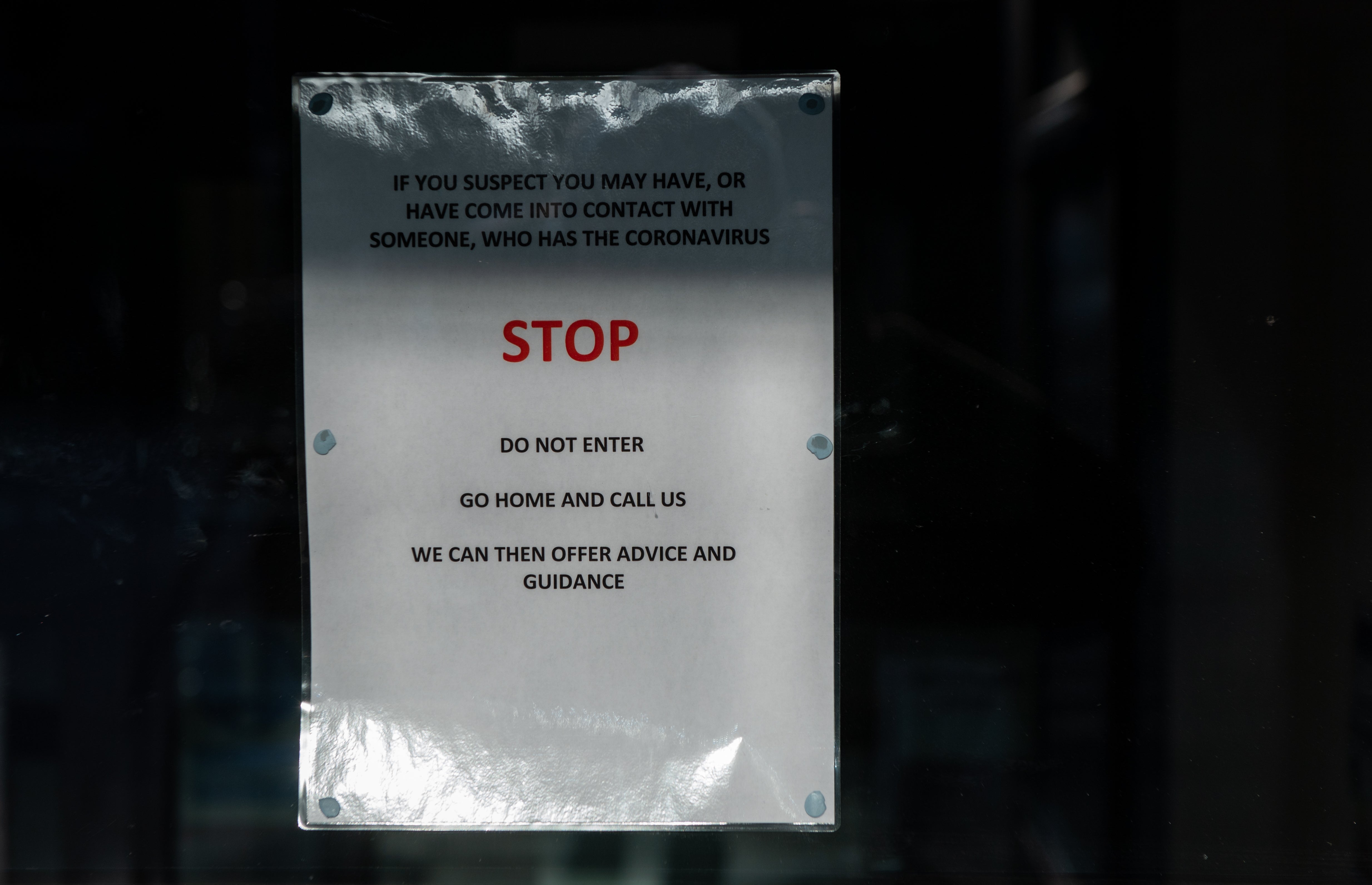

“What do I do now?” she asked. “I thought there would be a plan in place for something like this.” She was speaking in February last year. Neither of us realised the gravity of her words at the time. She was among the first people in the UK told to self-isolate. It was before the term was widely understood; very little was in those first days of the outbreak in Brighton.

There had been only two Covid cases reported elsewhere in the UK. A university student and his mother, who had flown in from Wuhan, both tested positive in York. The cases were made public on 31 January, and they were said to have been contained. But it was in Brighton that the first major cluster broke out, where the disease first seriously threatened to spread – and where we first found that it might not, as the authorities claimed, be under control.

This was more than a month before the national lockdown came into force. I was working as a reporter on the local newspaper. In the newsroom of the Brighton Argus, we were furiously trying to build up a picture of what was happening. It was my job to carry out the weekly vox pops. I would sprint down the steps of our seafront office and interview anyone who would stop for a photo.

People weren’t afraid, but, like most of us at that time, they weren’t informed. I spoke to a chef who told me with a straight face that smoking cannabis provided sound protection. “Working in the kitchen, I know all about viruses and bacteria,” he said. A dad pushing a pram said we should all be concerned about a super-virus – but Covid-19, he explained, wasn’t it.

I was told the flu kills more people than coronavirus, that one of the first cases was actually “a guy in hospital with a bad hangover”, and that everything would soon be under control. “These things have been handled well in the past,” one student explained. This was the day before the first case was reported in Brighton, on 6 February.

Soon we were taking call after call from people frightened about the spread of the virus. There were doctors, nurses, teachers, students, parents, staff at care homes, pubs, shops, restaurants. As the first wave began to break over the city, the calls kept flooding in. It wasn’t long before we were speaking to undertakers, and the families of the dead.

We quickly learned Brighton’s presumed patient zero was so-called “super-spreader” Steve Walsh, from Hove, who contracted the virus on a business trip in Singapore. He inadvertently infected several people around him, putting Brighton at the epicentre of the country’s coronavirus crisis. Public Health England scrambled to trace his contacts. Several had tested positive, and between them they had now come into contact with hundreds of people.

More cases were reported in the days that followed. It wasn’t clear to us at this point if these were fresh infections or prior contacts of Walsh who had already been isolated. This was the first major test of PHE’s infection containment strategy, and the virus had a head start.

My weekly vox pops revealed a change in the mood on the street. There was more fear in people’s voices now. Shops soon began selling out of face masks and hand sanitiser. It was around this time that the tip-offs began to come in.

Not knowing he was infected, Walsh had been living life as usual in Brighton for days before testing positive. He’d been to a yoga class and had a drink in the pub. As venues around the city closed and contacts were told to isolate, people rang in. In the absence of any real official information, a kind of DIY citizens’ track and trace system sprang up.

We learnt that two of Walsh’s infected contacts were doctors. Between them, they had worked at an A&E unit and two GP practices, as well as visiting a nursing home in Brighton. In the following days we got calls from patients whose GP surgeries had suddenly shut their doors.

Workers in hazmat suits were photographed deep-cleaning the County Oak Medical Centre in Hove. People wanted to know why. They were told, on the surgery’s answerphone, there was “an urgent operational health and safety reason”. Soon schools began to send out letters telling parents that pupils or teachers had been contacted by PHE and asked to self-isolate.

In the newsroom, we drew out a web of cases on the wall. We looked for links, published timelines and tried to pinpoint spots where the virus could have been passed on. We got calls from people desperately wanting to know if it was safe to visit the doctor or send their children to school.

Initially it was hitting us right in the face and we were seeing people die day in, day out. But now, you just get on with it. You don’t get that feeling of panic when you need to go to work anymore. It’s like you become a zombie to it. You become acclimatised. It’s just another day

Like us, the people ringing in believed we would all be safer if we had accurate information about the level of risk we faced. People who might have been exposed to the virus could come forward, and the city would be better prepared. We thought people had a right to know. But the authorities repeatedly refused to comment.

Caroline Lucas, Brighton’s MP, recalls the disarray at the time: “I remember very clearly the huge amount of anxiety and confusion for people in the city because of a lack of clear, timely and relevant information.”

“There should have been a coherent, consistent public health campaign from the start and there wasn’t,” she added. “When we needed a sure-footed response from ministers, we got the opposite.” Others were even more scathing. Local councillor Professor Samer Bagaeen, a member of the city’s health board, claimed the authorities had allowed coronavirus to “spiral out of control” by “intentionally hiding” information – something they denied.

Several days after the first Brighton case, I took a call from a frontline clinician tasked with controlling the spread of coronavirus in the county. He described the handling of the outbreak as “absolutely shambolic”. He spoke of a failure to identify and test for potential cases, and confusion among health bodies. He claimed it had taken eight to 10 valuable days to agree on a plan of action.

Medics and scientists had begun warning that it would not be feasible to catch and contain every case before infected patients managed to pass the virus on. Nevertheless, in early March, PHE assured The Argus there had been “no onward transmission of the virus”.

All the while, news teams from around the country had started to descend on Brighton. My colleagues and I spoke on the BBC, ITV, LBC and we appeared in a Channel 4 documentary filmed in our offices. The modest Argus newsroom became a part of the bigger story.

And the phones kept ringing. I spoke to undertakers who said they were unable to bury the dead safely without proper protective equipment. Care homes were crying out for protective kit – a volunteer told me more than 60 in the county were reliant on charity for basic supplies. He was giving them out from his car boot. Where were the deliveries the government had promised?

We heard harrowing stories from intensive care. An ICU nurse broke into tears as she described tending to terrified patients in their final moments on a Covid-19 red ward. She told me medical staff had been paying with their lives for their hard work.

Several weeks in, my colleague Jody Doherty-Cove landed another major national story. Three-quarters of the residents at a nursing home in Hove had become infected. This was one of the first such outbreaks to make the headlines, at a time when the crisis in care homes was only just being recognised.

Earlier this week, I spoke to Lucy Rutler, whose father was among those who died after contracting coronavirus in that first cluster of infections at the Oaklands Nursing Home. His name was Hugh Francis. He was 85 and a retired doctor. He’d been monitoring his own symptoms from his bed. “He knew what was happening to him,” Lucy said. “It was awful. At that point there was so little information and everyone was so afraid.”

Lucy was among the first to experience the pain of being unable to be with a loved one in their last moments. She said: “In that first outbreak, people who lost their loved ones did not get to say goodbye – they didn’t get to hold their hands. One of the hardest things was knowing my dad died without his family by his side.” Lucy praised the care workers who looked after her father. “They did their best in a very difficult time,” she said.

I wanted to speak again to others caught up in the crisis a year ago, and find out how some of those I talked to at the time are coping now.

Next week, Mike Dicks is getting his first vaccination. For more than 300 days he has been shielding, leaving his flat only to put out the bins and get blood tests. He suffers from chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and is at high risk from Covid-19. The cancer affects white blood cells and prevents his body from fending off viruses.

During the first wave, he and more than 2 million other vulnerable people in the UK were warned to stay home and remain in total isolation for at least 12 weeks. Mike and I have kept in touch throughout the crisis. When, last summer, the government deemed it was safe for shielders to venture outside, he told me he would not stop isolating until he felt the virus was under control.

Next week’s jab brings hope that he will one day be able to see his son again after 10 months in isolation. “I’ve been trying to think a long way ahead,” he said. “It helps me deal with things.” There is light at the end of the tunnel, even as many are still confronting the worst of the virus.

An undertaker I spoke to in Brighton during the first wave says the crisis now feels more severe than at the most worrying moments last year. “We are run off our feet,” he said. “January is a busy month as it is – it’s been even harder with Covid on top.” He expects February to be another difficult month for families across the county.

And the nurse told to self-isolate at the start of the pandemic now feels she is in the eye of a storm. She tested negative after that first terrifying encounter with a suspected Covid patient. She and her husband have both had the virus since, though their children were not affected.

“We didn’t have the option of sending them away this time,” she said. “We just had to get on with it.” She looks back on the panic in her voice during that harrowing phone call to me last year. “It seems like so far in the past – it’s different now,” she said.

Back at work, the mounting crisis at her hospital has brought a strange sense of calm. She passes the beds of the sick, and says she feels “like a soldier who’s been at war for a long time”. She remembers the dread she felt as she watched the number of people coming into the hospital climb at the start of the second wave.

“Initially it was hitting us right in the face and we were seeing people die day in, day out. But now, you just get on with it. You don’t get the flashbacks in the same way. You don’t get that feeling of panic when you need to go to work anymore. It’s like you become a zombie to it. You become acclimatised. It’s just another day.”

We are still in lockdown, with more than 100,000 dead and hundreds more dying every day. Looking back at those first frightening weeks, it is the voices and stories of the callers who opened up over the phone that I remember most. I am glad we wrote them down.

When people look back in 50 or a 100 or 500 years’ time, they will want to know how people felt as they lived through this crisis.

And they will be able to read about Mike, the brave cancer patient who spent months alone in his flat, and Lucy, the daughter who could not hold her dying father’s hand, and the scared nurse who felt like a battle-weary soldier as she stood at the bedsides of the sick.

Those stories, of suffering and strength, are there because all over the city people called in – and we picked up the phone.

This article was amended on February 8, 2021, to add the word ‘major’ to the headline and to remove a reference to one man ‘infecting hundreds of people’ from the photographic caption.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments