A pox on your houses: How disease and pandemics have shaped history and remade empires

The Black Death wiped out 50 years of economic progress, destroying empires and building others. Borzou Daragahi traces the history of plagues and disease, and wonders what our post-pandemic future will look like

When Abu Sa’id Bahadur Khan, the last ruler of the Mongol empire’s Ilkhanate, surveyed his domain in the year 1330 he must have been really pleased with himself. He held power over a vast region stretching from the Indus River to the Meditarranean. It included a network of trade and military routes that stretched thousands of miles across Persia and the Fertile Crescent into Anatolia.

The caravans carrying spices and fabrics generated vast wealth for him and his courtesans. Profits from tolls, taxes and tributes sustained a life of splendour for him, his wives, and his offspring. He was only 25 years old. Within five years, it was all gone. The Ilkhanate had disintegrated into a collection of squabbling armies overseen by lesser warlords, his achievements and successes forever obscured by time. Abu Sa’id himself was dead, either at the hands of his own men or by a surging disease that was the primary cause of the unrest and agony throughout his domain: the Black Death.

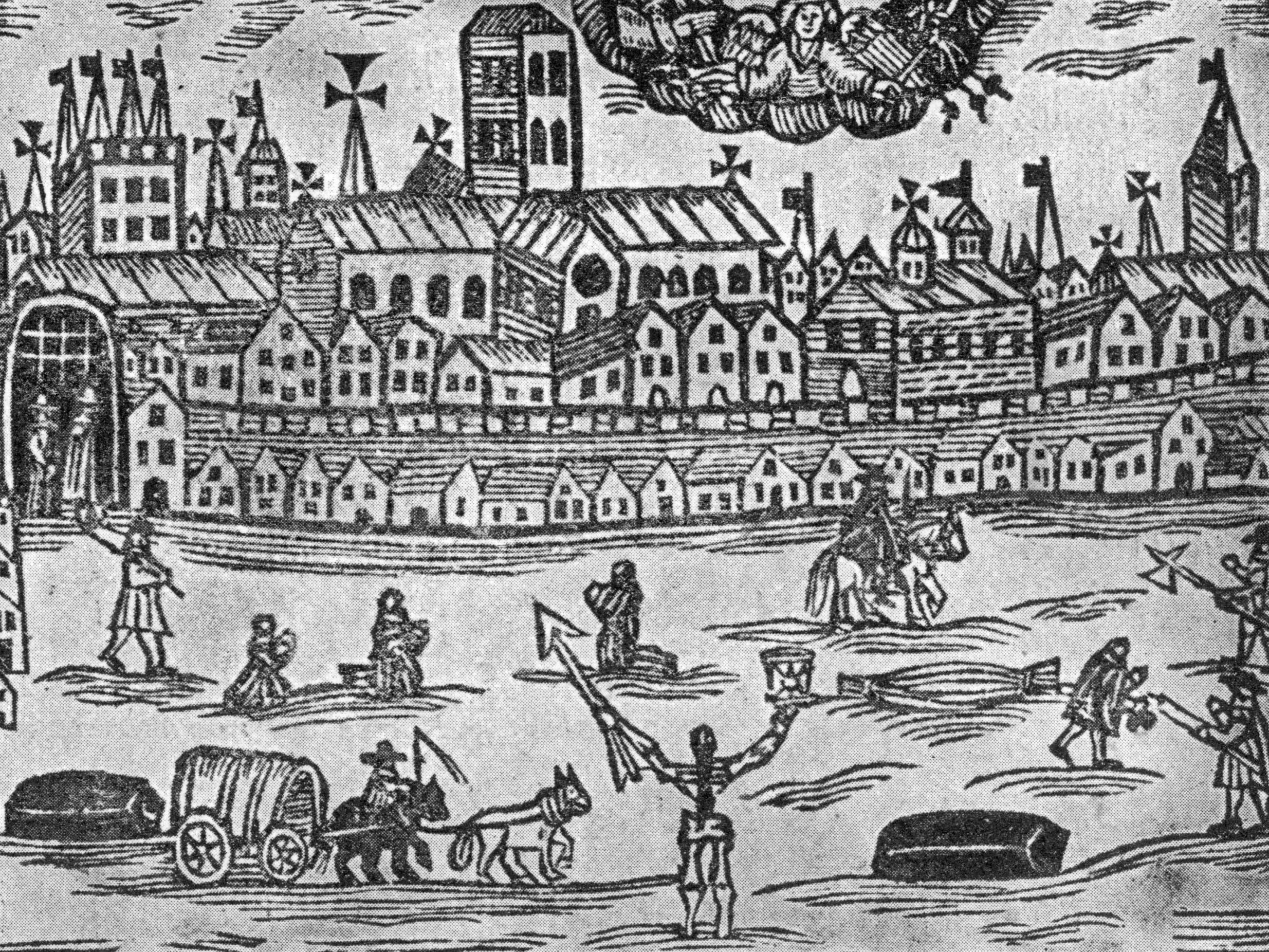

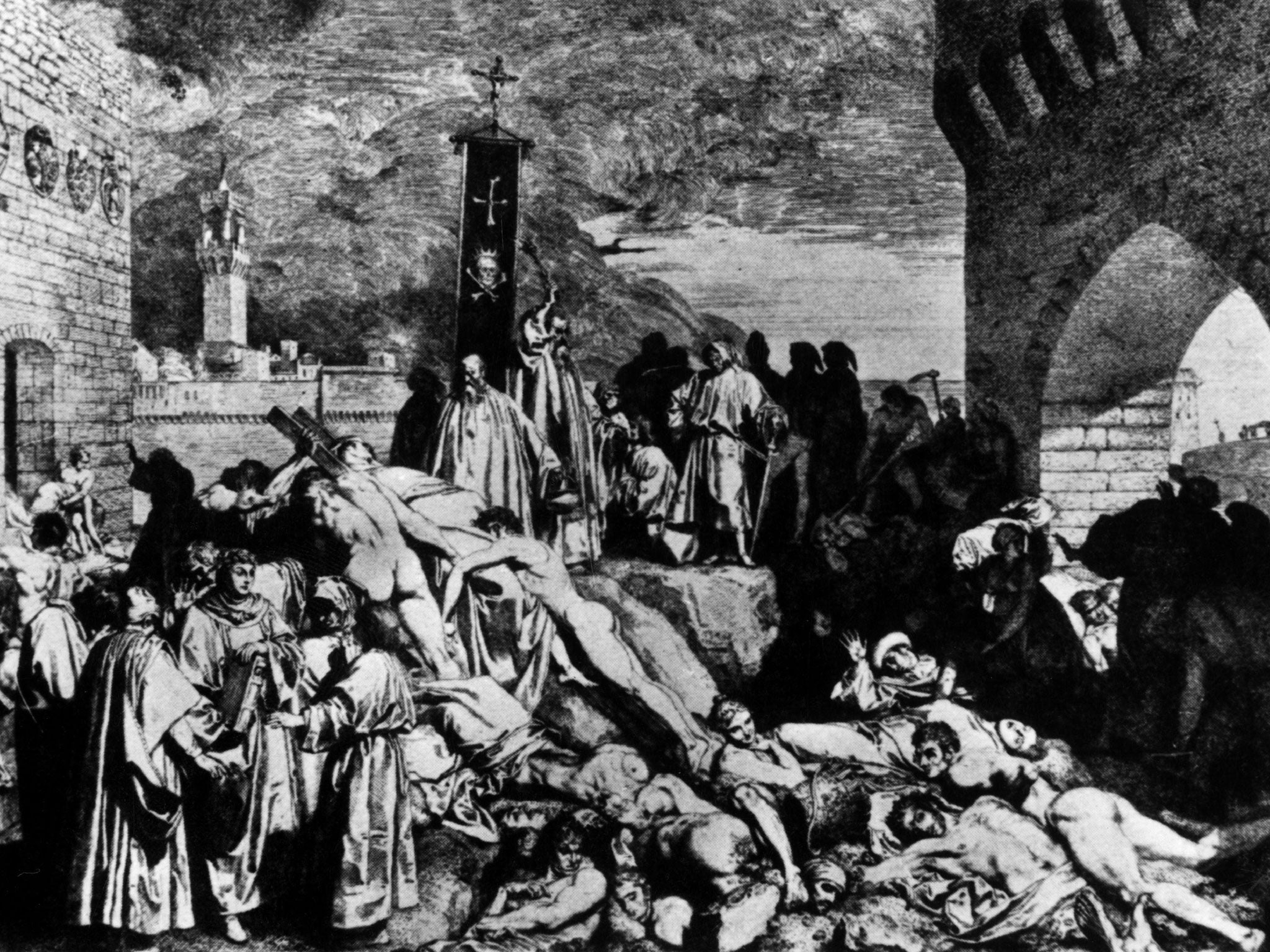

The pandemic had swept across Eurasia and left tens of millions dead. Just as the coronavirus spread across the world via jet planes that are the lifeblood of today’s global economy, the deadly 14th-century pathogen traversed the same desert trade routes and sea channels that were the source of the empire’s power and wealth. The Black Death killed as many as 70 per cent of the people in the cities, towns and villages through which it raced. According to scholars, it wiped out an estimated 50 years of economic growth. In recent years, scholars and scientists have done genetic tracing of skeletal remains to sketch out the Black Death’s course through the world.

The coronavirus pandemic now gripping the planet is a once-in-a-lifetime disaster that has drastically changed the rhythms of global commerce and daily life. The passenger planes crisscrossing the world have largely stopped, decreasing by 60 per cent. Streets and motorways filled with cars during commuting hours are still. One report suggests UK road traffic has dropped to 1955 levels. The disease threatens the livelihoods of billions of people, as well as the lives of millions. Even in the unlikely event a vaccine is developed by year’s end, as Donald Trump has predicted, the aftermath of the disruption will reverberate for decades.

Throughout history, disease has frequently reshaped politics and society, altered the course of empires, changed the trajectories of wars, and drastically impacted civilisations. “People are waking up to pandemics,” says Uli Schamiloglu, a professor of the history of diseases at Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan. “Throughout Eurasia, you have had outbreaks of disease that have changed the course of history.”

Despite the Aids and Ebola epidemics of recent decades, historians of disease say we’ve been living in a Golden Age of maladies that followed the introduction of penicillin, used to treat bacterial infections, vaccines to prevent viruses, and public health and hygiene innovations, which have stemmed the tide of illnesses such as cholera. For much of history, plagues have shadowed us, shaped relations between people, feeding into bigotry and prejudices, wiping out fortunes and creating new ones. Smallpox famously ravaged the indigenous populations of the Americas, paving the way for European colonisation.

Measles wiped out the monarchy overseeing the Hawaiian islands in 1848. We’ve already had tastes of the sorts of impacts disease can have. Mad Cow disease badly damaged UK agriculture, and Swine Flu dealt a near deathblow to Egypt’s pork industry, which struck hard at the country’s Coptic Christians. According to a Centres for Disease Control paper, a 2015 outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Mers) in the Republic of Korea, which caused only 32 deaths, cost the country’s tourism sector $2.6 billion.

The Black Death wiped away decades of economic progress in 14th-century Eurasia, destroying skilled crafts, draining labour supplies, and leaving harvests uncollected. The current pandemic is already laying waste to industries such as air travel and tourism, and economists worry that coronavirus could wreak lasting havoc on much of the world. The World Bank predicts sub-Saharan African will experience its first recession in a quarter of a century, with half of all jobs lost, and South Asia will suffer more than at any time since the 1970s. It could take decades to make up the shortfalls. “This pandemic doesn’t strike proportionally,” says Stephen Casper, a professor of the history of science and associate director of the honours programme at Clarkson University, in upstate New York. “It will hit pilots and doctors harder than bankers. It takes a long time to train a doctor. It takes a long time to train a pilot.”

The panic is destroying us slowly. I don’t think anywhere near as many people are gonna be dead as the Black Death. The casualty is going to be our society and the way we live

In contrast to previous pandemics, the fear of coronavirus – speeding through the global electronic media – is having as much if not more of an impact than Covid-19 itself. Just as the 9/11 terrorist attacks reshaped our perceptions and protocols about security, so too will this pandemic reformulate the way we think about engaging in public spaces — from going to restaurants, to taking public transportation, and working in open-plan offices.

“It’s not that everyone’s dying of coronavirus,” says Paul Buell, a scholar who has studied the impact of diseases throughout Asia. “It’s that the panic is destroying us slowly. I don’t think anywhere near as many people are gonna be dead as the Black Death. The casualty is going to be our society and the way we live.”

In an ideal world, a global pandemic brings people together. What better time to acknowledge our common humanity and shared goals than an attack by an invisible pathogen that threatens all of us regardless of race, class, or national origin? But far more often than not, disease has increased hatred and polarisation, driving wedges between social classes and ethnic groups. Throughout world history, diseases have been associated with the poor or untouchables. Carriers or suspected carriers have been shunned, barred, quarantined in isolation – recall the leper colonies – or further stigmatised, as gay men were during the Aids epidemic of the 1980s.

Even during the first few months of the coronavirus crisis, there have been recriminations and divisions, with older people hysterically demonising the youth who flouted social distancing guidelines and celebrated spring break on the beaches of Florida. The pandemic has also amplified discrimination against the elderly, with many seemingly blaming their frailty and susceptibility to the pandemic for lockdown and social distancing measures that have brought the world economy to a halt. “Sacrifice the weak, reopen [Tennessee],” said a sign held up by one woman in the southern American state last month.

“There is a need to say that this group of people did something bad here,” says Casper. “To foreground a group of people strikes me as poorly thought out but consistent with what we’ve seen in past epidemics.”

On 8 May, the UN Secretary General, Antonio Guiterres, warned that the pandemic had unleashed a “tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scare-mongering” – targeting Jews, Muslims, migrants, refugees, and the elderly. Covid-19, he pleaded: “Does not care who we are, where we live, what we believe, or about any other distinction.”

In fact, disease has often exacerbated rather than eased armed conflicts. During the Black Death, the Mongol army, stricken by illness, famously catapulted the bodies of its dead into the besieged Crimean city of Caffa, in an account described by the Italian explorer Gabriel de Mussi. The account is likely the first known use of biological weaponry in history. But it would not be the last time armies sought to use disease as a weapon. Sir Jeffery Amherst, commander of the British forces in North America in the mid-18th century, allegedly assigned a subordinate to distribute smallpox-infested blankets from a military fort that had suffered an outbreak to Native American communities during the French-Indian War.

“Could it not be contrived to send the smallpox among those disaffected tribes of Indians?“ Amherst wrote. “We must, on this occasion, use every stratagem in our power to reduce them.”

And though military conventions stigmatise and international laws strictly forbid the use of biological weapons, even today’s combatants are not above exploiting a pandemic for military gain. In Libya and Yemen, for example, belligerents on all sides have sought to use the coronavirus pandemic to make battlefield advances, despite the entreaties of international aid organisations. Iran and the United States have sharpened their rhetoric and brinkmanship, each convinced the other is too distracted grappling with the pandemic to respond.

Just this month came word of a thwarted attempt by a group led by former American military officials to overthrow the government of Venezuela, which is struggling despite a battered economy to contain the pandemic. And Israel has been accused of using the cover of Covid to step up its bombing campaign in Syria. Disease has been an underrated catalyst for political change, but the outcome is never wholly predictable. For example, while the Black Death devastated the Mongol system, it seems to have led to the rises of the absolute state in Europe, and bolstered the power of the church.

“What happens when you have huge amounts of demographic decline in a short period of time?” asks Schamiloglu. “In the nomadic states, it leads to total anarchy. For Russia and Europe, it seems to have helped more states become stronger. There was increased religiosity, increased morbidity and an obsession with death.”

The 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic killed tens of millions of people. But while there is evidence that it caused immediate economic distress, it was followed by a decade of immense growth

Plagues and pandemics repeatedly pummelled British-controlled India. Authorities responded by blaming the hygiene habits of the poor; and there are accounts of families being turned out of their homes and their meagre possessions burnt in early 20th century Bombay for being suspected carriers of disease. The Spanish Flu killed about 50 million people worldwide. When this pandemic arrived on India’s shores in 1918, it hit like no other. Up to 12 million people died in India, although historians cannot agree on the actual number. The state’s mishandling of the pandemic fanned the flames of a new nationalism that would eventually lead to massive political change, and the eventual birth of modern India.

“When the pandemic ended you had deep anger at the ruling elites,” says Sanjoy Bhattacharya, a professor of the history of medicine at the University of York. “It brought out the nationalists such as Mahatma Gandhi.”

Just as disease tends to pit the well off against the poor, its aftermath often forces scrutiny of power, and brings about political change. Outbreaks of cholera in the 19th century eventually gave birth to the concept of public health in the 1870s, to decent sanitation and sewerage systems, and the rise of progressive mass politics in western states. Modern science explained the origins of disease in viruses and bacteria rather than the moral failings of the poor or underclass. The rich and captains of industry came to realise that allowing the poor to fester in disease-stricken Dickensian urban hellscapes was not only economically damaging and morally repugnant – but a threat to themselves.

It was the outbreak of malaria among US soldiers during the Second World War that prompted the creation of what became the Centres for Disease Control, the once-admired and frequently copied American institution that battles pandemics. It was the 2003 outbreak of the SARS coronavirus in Far East Asia that prompted the founding eight years later of Singapore’s Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, which has been celebrated for devising the city-state’s relatively successful response to the coronavirus pandemic.

In US, Britain and elsewhere, the coronavirus is forcing scrutiny of the neo-liberal elites and the dismantling of the welfare state in favour of the gig economy. Bankers, corporate lawyers, and CEOs get to shelter in luxury condos while underpaid supermarket clerks, nurses and delivery guys risk their health to keep them sustained. A reckoning may come. “What pandemics do is expose the rifts between the haves and the have nots,” Bhattacharya says. “Those fractures come out. Unchecked pandemics and disease are certainly a threat to the structures that support our economic systems today.”

All is not lost. The global economy could well pull through. The 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic killed an estimated 50 million people. But while there is evidence that it caused immediate economic distress, it was followed by a decade of immense growth that was only curtailed by the market plunge of 1929.

“There was a lot of effort on a public level to forget about what happened,” says Casper. “This ‘moving-forwardism’ is the way newspapers were talking, and the way captains of industry and leaders are now speaking. I imagine we’ll also see a similar push for normalcy.”

25m

People estimated to have died from the plague

The world also hustled past the 1968 Hong Kong flu pandemic, which killed millions worldwide, but didn’t appear to calm that era’s can-do spirit. But careful handling of the aftermath of a pandemic is of crucial importance. An extraordinary study released recently by the Federal Reserve Bank in New York traced the rise of extremism in Nazi Germany to aftermath of the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. The study, prepared by economist Kristian Blickle, found a correlation between high influenza deaths and an increase in the share of votes won by Nazis in crucial 1932 and 1933 elections. Why? Possibly because those areas of Germany that suffered the highest population loss during the pandemic wound up spending less per capita in the following decade on people, including on education and programmes for youth.

Historical texts, newspaper accounts and dry economic analyses fail to draw a full picture of the effects of disease. The countless ways in which disease destroys human lives are often lost to history. Polio decimated entire communities, destroying individual potentials and draining families of income. Even the current pandemic is hurting children forced to stay indoors, depriving some of precious months of schooling — especially if their parents are too harried or simply not intellectually capable of teaching them.

Bhattacharya notes that sometimes he takes his students out for coffee or lunch, to talk about their work and careers. Giving occasional lectures over the internet, he’s no longer able to do that. “If you multiply that exponentially you can see what a deep economic impact it could have,” he says.

What we fail to really understand about diseases is the magnitude of their impact on private lives. “One of the things that we learn from any sort of pandemic or outbreak is that the stress and implications for individual families is very high,” says Clarkson. “And it’s really easy to force people to take their grief private.”

In the aftermath of any pandemic, people should take the time to grieve, and to consider and account for all that has been lost. Buell, the scholar, recalls a story of an Italian priest in Europe after the Black Death singing the verses of a well-known religious hymn to a tune that sounded strange and unfamiliar to a visitor from abroad.

“Why do you sing it this way?” the visitor asked.

“Everyone who knew how to sing it,” explained the priest, “has died.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments