How to tackle climate change as the world recovers from coronavirus

As the world slowly emerges from the shock of the coronavirus pandemic it faces stark choices. None will be more important than how it responds to the existential challenge of climate change, writes Jon Bloomfield

What percentage of journeys made each year in Birmingham, Copenhagen and Berlin are cycled? Make a guess. Remember, in these three major European cities, the price of bikes is comparable; the terrain is relatively flat; the weather is broadly similar; and Birmingham is the youngest city in Europe.

The latest figures indicate that cycling makes up 40 per cent of the modal share in Copenhagen, 15 per cent in Berlin and just 1 per cent in Birmingham. Were you close? And whether you were or weren’t, the numbers pose the question: why are the differences so sharp? Basically, the answer is social and political, rather than technical. Copenhagen’s politicians, under the influence of an innovative urban architect Jan Gehl, began to change their system of urban design and planning in the 1960s. At the moment that Spaghetti Junction became the architectural symbol of Birmingham, Copenhagen moved in the opposite direction, gaining public support for moving towards a more human-centred city. Ever since, towns and cities across Europe have been slowly breaking with decades of car-centric thinking.

The pace has been uneven – strongest in Scandinavia, the Netherlands and Germany – but many have been experimenting with solutions that give greater prominence to public transport while offering cyclists, and increasingly pedestrians, more and safer space within their urban infrastructure. In other words, transforming key aspects of the urban mobility system. This is just one example of a wider story. To move from a high carbon to a low carbon society and meet the targets set by the International Panel on Climate Change, we have to change the ways we work, live and move and the systems that underpin them.

As Covid-19 exposes humanity’s fragile relationship with the natural world, it serves as a wakeup call to the urgency of the climate crisis. There might eventually be a vaccine for coronavirus or, as with HIV and Aids, ways to treat it: there is no magic bullet to cool the planet. Only concerted, comprehensive action can do that. Across Europe, there is a groundswell of activity as villages, towns and cities tackle the issues of climate change. Thousands of often imaginative and innovative low carbon projects are underway; 9,500 European civic leaders have signed up to the Covenant of Mayors and made ambitious declarations of intent for their own municipality, with two-thirds having drafted local action plans. In the UK there has been a flurry of commitments from councils to go carbon-free by 2030.

Progress is being made. There are concerted efforts within the scientific and policy community to analyse the most effective ways to shift to a low carbon society. Before “transition” became a buzz word of football managers and pundits, it had emerged from social scientists and environmentalists working with those from the natural sciences and policy-making. It argues that to tackle a huge economic and social challenge like climate change a comprehensive approach is required which starts with the recognition that the key high-carbon producing systems of everyday life such as energy, buildings and transport have to change. A systems approach pulls together all the relevant stakeholders in these systems to get them to consider the barriers to change and how – separately and together – the stakeholders can innovate so that low carbon initiatives can displace the high carbon ones and become dominant in the system, as has happened in Copenhagen’s mobility system and as renewables are displacing fossil fuels in Germany’s energy system. Thus, sustainable transitions is a systems model rather than one focused on individual product innovation. It looks to transform whole systems rather than replace a single component.

There are countless, good examples of transition work underway. Transforming the energy efficiency of housing stock is an absolutely key area

Over the past two decades this transitions approach to innovation and change has been adopted by national innovation agencies, international institutions and the European Commission. I was involved in getting elements of this thinking embedded within the EU’s Climate Knowledge Innovation Community (KIC) project. When it was launched a decade ago we designed a new type of knowledge development programme – Pioneers into Practice – arranged for practitioners, policymakers and activists organised on the principles of transition thinking.

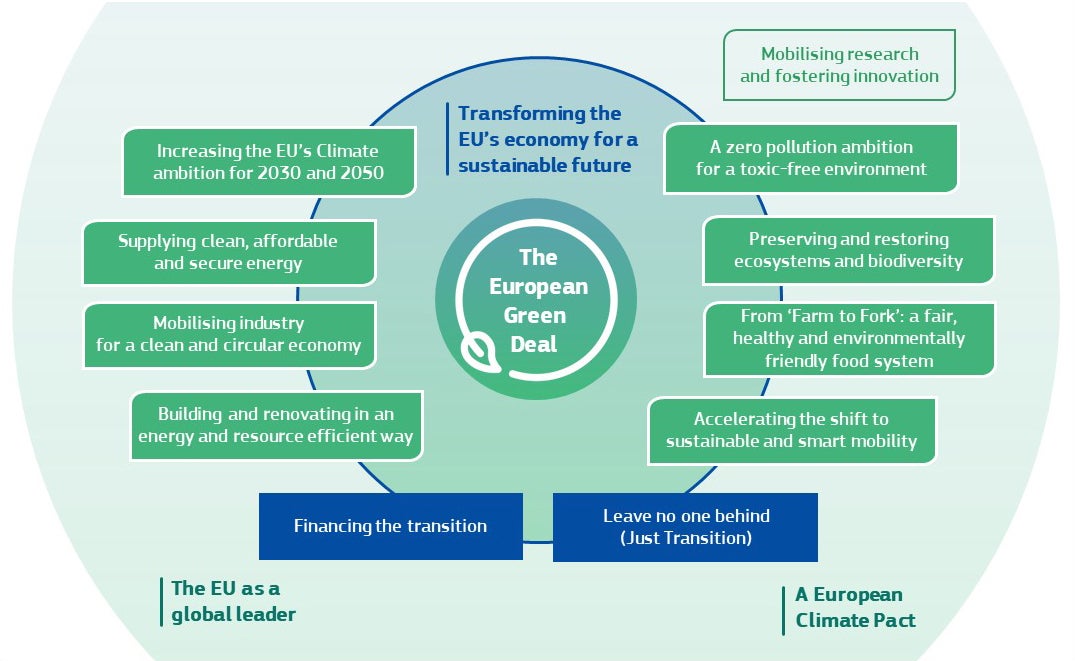

This thinking is crucial because it sets out a pathway to the crucial question of how to make a transition. Rather than focusing solely on the size of investments or on general talk of a “green revolution”, system innovation offers pathways of sustainability transition which can address each of the key spheres with high pollution-emitting activities. Unlike the generic approach on a green new deal among US Democrats or in Labour’s 2019 manifesto, the EU in its launch of the European Green Deal (EGD) last December specifically identified five key areas – energy, buildings, industry, mobility and food – where focused transitions are required.

The size of the EU programme has yet to be agreed. The initial proposal was undoubtedly too small and dependent on a range of uncertain financial leverage mechanisms. As negotiations continue on Europe’s post-Covid recovery programme there is potential for this EGD budget to expand considerably, as France and Germany are now proposing. But what the Commission has done – albeit in dry, technical language – is to set out the pathways to change, the areas that need consistent, applied attention. That gives a template for countries and cities to follow. This is an opportunity for both the UK and Europe to bring coherence and give direction to the multitude of climate change activities that are taking place. In the period before the UK hosts COP26, the next crucial world conference on climate change, now scheduled for Glasgow in 2021, here is a major opportunity for climate leadership.

Systemic initiatives are emerging, often led by key policymakers and practitioners influenced by transitions thinking. Keith Budden is an example of one such practitioner. He has been working on environmental issues at the grassroots for the past 25 years in the West Midlands in both the public and private sectors. Having worked on waste and recycling, urban regeneration and energy, he is now focused on transport and mobility working as head of business development for the Centre of Excellence for Low Carbon and Fuel Cell technologies (Cenex). Budden has helped to broaden its focus in line with sustainable transitions thinking. In a host of projects and programmes, “we retain our strong technical knowledge base on the development of electric and hydrogen vehicles but we place these within the context of the overall mobility system. We then explore the linkages between this and the energy system. So we are not just researching on cleaner vehicles but thinking about mobility as a whole; how and why people move and then the planning requirements they need for this.”

Cenex works closely with Nottingham City Council where a combination of strong political leadership and knowledgeable officials has enabled the city to become a trailblazer on mobility. It is the only city in the UK to have introduced a Workplace Parking Levy, which places a charge on commuter parking spaces provided by businesses. This gives it the capital to invest in its public transport infrastructure. The city has a 34-kilometre tram system – the UK’s largest fleet of battery-electric buses – and is making significant investments in cycling infrastructure. It was the first city outside London with a multi-operator public transport smartcard (the “Robin Hood” card). Despite this high standard of available public transport and active travel infrastructure, vehicle congestion and air quality remain key challenges along with how to plan the infrastructure for non-fossil fuel vehicles and the best ways to utilise digital technology to the city’s mobility system.

Cenex’s Strategy and Mobility team is working with local authorities across Europe on a Climate-KIC programme on shared, sustainable mobility exploring the potential of both new urban mobility models and of using digital technology for public purposes. Budden argues that “in late 19th century Birmingham, Joseph Chamberlain secured access to gas and water for all citizens. We now need core services around access to the digital world which could be really important for transforming our mobility options”. A municipal Uber anyone?

In each of the key systems identified by the European Green Deal, there are countless, good examples of transition work underway. Transforming the energy efficiency of housing stock is an absolutely key area. The wholesale renovation of housing demands similar ingredients of a systems approach to that for mobility: consistent political leadership, capable officer stewardship, long-term commitment and wider citizen support. ABG is Frankfurt’s main housing company with 52,000 units. Bernd Utesch is the chief officer of its spinoff innovation company ABGNova, which leads much of its innovation transitions.

A red-green coalition initially led the way with the remit to improve the energy efficiency of buildings across the city. An extensive programme of enhanced district heating followed. The city, then under a Christian Democratic mayor, turned its attention to enforcing higher building standards. This has involved three elements: an insistence on a high quality regulatory and procurement framework; a willingness to introduce and test out new building techniques; and a programme geared to changing citizens’ behaviour with regard to energy usage. Most notably, the city has pioneered the introduction of passive housing, a quality standard combining high comfort with very low energy consumption and lower energy bills, a vital way to link environmental and social goals by showing the potential for climate change measures both to help low-income households combat fuel poverty as well as reduce emissions. Following successful pilots, the passive house (PH) construction method became the standard construction model for the municipality. The PH Standard is defined by a maximum heating energy demand of 15 kWh/per square metre/per year at least 10 times less than the normal demand.

“ABG have trained the architects, planning staff and also the building workers since a key issue is the quality of the installation works. And with a growing market we have brought down the cost gap between ordinary housing and the passive standard,” says Utesch. The strength of Germany’s social market economy means that Frankfurt has not just shaped the market through its regulations but directly acted within it through its own municipal housing company.

An ambitious blueprint for Britain’s low carbon future’ published in October 2017 states that ‘moving to a productive low carbon economy cannot be achieved by central government alone’

Bianca Dragomir is one of a cohort of Climate-KIC pioneers who have gone on to apply transition thinking in practice. Her experiences show the potential for mobilising industry in new ways, another crucial arena identified in the European Green Deal prospectus. She runs Avaesen, an industrial cluster focused on renewable energy in the Valencia region of Spain. It encompasses 120 businesses with an annual turnover of €3bn and more than 6,000 green jobs. She has applied the system innovation thinking she acquired in the Pioneers into Practice programme in her cluster development work with Avaesen. She describes three elements to this work. Firstly, they changed the economic activity and perspective of the cluster so that it was more self-reliant rather than just waiting for subsidies. Secondly, they extended its agenda so that it encompassed policy work, for example convincing the regional government about the potential of the renewable energy sector and the need for new energy policies, such as on solar power.

Thirdly, it broadened still further so that the cluster became the hub of a wider movement, bringing in research institutes and universities as well as the cities and small towns which are crucial to the cluster’s development. They set up a Smart Cities network, which developed sustainable energy plans for many small towns in the region and which then issued tenders for new projects. Dragomir believes “these are the type of climate innovation clusters we need to see across the whole of Europe. There’s a huge opportunity for the cleantech sector. Through the Smart Cities Think Tank we link municipalities as problem owners with companies as solution providers, and venture capitalists and business angels as funders, to co-create cities of the future.”

The think tank is also accessible to local citizens with scope for them to feed in ideas. To make a success of its green deal, this is the type of thinking that needs to be transferred to many of Europe’s 2,500 industrial clusters. The cluster action process which Dragomir and her project colleagues have developed outlines a seven-step programme for broadening the cluster horizon. She says: “We’ll need smarter clusters for the European Green Deal to work.”

European and national government strategies have to link the local to the global. The UK government is aware of the local dimension. Its “Clean Growth Strategy: An ambitious blueprint for Britain’s low carbon future” published in October 2017 states that “moving to a productive low carbon economy cannot be achieved by central government alone; it is a shared responsibility across the country. Local areas are best placed to drive emission reductions through their unique position of managing policy on land, buildings, water, waste and transport.”

Europe’s Green Deal offers a new paradigm where growing the economy and greening the economy go hand in hand. One of the big challenges will be getting that shift in mindset understood

There are two major obstacles here. Firstly, fine words are contradicted by centralist practice. Local government in the UK has experienced decades of concerted denigration and resource reduction which leave it ill-equipped to follow the best practices from Frankfurt, Valencia and elsewhere. Secondly, 40 years of the “market knows best” ideology has left most economic development and planning officers seeing “the environment” as very much a secondary consideration. In Frankfurt, politicians and officers pushed to extend and go beyond national guidelines. Budden’s experiences in local government serve as a warning. “The officers believe that their job is to make it as easy as possible for business,” he says.

“So they won’t insist on supplementary planning guidelines which would demand that property developers follow higher energy efficiency building standards or insist on district heating or renewable energy on new housing developments.” This makes changing the broader culture crucial. “Even now, local authorities who have signed up for the climate emergency haven’t thought it through. Our mindset still sees economic development and environmental protection as distinct and the former has priority. ‘We can’t impose any new burdens on business’ remains the common mantra.”

Europe’s Green Deal offers a new paradigm where growing the economy and greening the economy go hand in hand. One of the big challenges will be getting that shift in mindset understood and acted upon by economic development specialists and politicians across the UK and Europe.

Spreading this learning across the UK and Europe is crucial, so that politicians don’t endlessly reinvent the wheel and policymakers crystallise best practice and apply it in their own settings. That is why the role of environmental networks like UK100, the Rapid Transition Alliance, Energy Cities and Polis, the Eurocities network and the studies of the EU’s Joint Research Centres are so crucial. The Transitions Hub in Brussels serves as Climate-KIC’s centre of excellence for creating new tools and methods for problem-solving, supporting policymaking and community learning on innovation for climate change. Cristian Matti has run the small unit for five years drawing on the experiences of Climate-KIC’s innovation and education programmes to develop the practical knowledge needed for policymakers and practitioners in their daily work.

The Hub’s new handbook focuses on practical participatory methods helping stakeholders to grasp all the key elements of their local system, the points of resistance to change and how to overcome them. This is linked with the analytical frameworks necessary to understand and distinguish the distinct features of different systems, whether it be food or mobility, and how they combine together.

“It’s a complex journey but we are translating thinking into practice,” says Matti. “We want to spread this thinking widely. We are working with EU agencies on the idea of transition labs and policy applications. We have embarked on several initiatives to work with countries, regions and cities on their climate transition, as with Slovenia. We want to share our insights with cities, companies and citizens all over Europe.”

As the world slowly emerges from the shock of the coronavirus pandemic it faces stark choices. None will be more important than how it responds to the existential challenge of climate change. The COP26 world climate change conference in Glasgow next year will show how seriously the world is facing up to the task. Will the EU recovery programme be a green deal on steroids? Will China and India ramp up their renewable energy programmes? For all, will recovering the economy go hand in hand with greening the economy? And more broadly, will transition approaches be the thread running through policy?

It’s an important moment for the UK as chair of the conference. Sir John Gieve, former deputy governor of the Bank of England, has called for a large scale investment programme to foster economic recovery with the Green New Deal at its centre. That should be the UK government’s policy ambition. Gieve recognises that these types of transition can’t be achieved top-down by centralised edicts. In all the key emissions areas, it needs concerted action by all stakeholders orchestrated at a city-scale.

As Tom Mitchell, who has run Climate-KIC’s UK operations and is now its chief strategy officer, puts it: “The UK’s hosting of COP26 means the leaders and countries from around the world will be looking to the UK for inspiration. This cannot just be adding some pro-climate strings to Covid-19 bailouts. Instead, the UK must show how to unlock progress both in broad, comprehensive transition approaches and in some of the toughest areas of climate action, where very little progress has been made so far. Covid-19 recovery creates a new landscape of possibilities here, with vast employment opportunities in nature-friendly farming, rewilding our degraded landscapes or replacing the UK’s 25 million gas boilers with green heating alternatives. It offers a chance to link the local with the global.”

Jon Bloomfield is an honorary research fellow at the Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Birmingham and a policy advisor to the EU’s Climate-KIC programme

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments