Amid growing panic and outrage, coronavirus fears are uniting those at war in Hong Kong

A city once wracked by violent protests is facing another crisis – but one that could unite both sides of the political spectrum. As borders close, supplies run out and medical workers go on strike, Brian McGleenon reports from a nation on the edge

Wuhan is in lockdown. Quarantined within their high rise apartments, residents call out to one another from darkened windows. “Wuhan jiayou”, they shout, or “stay strong Wuhan”. Sometimes they break into spontaneous songs of solidarity for the city at the epicentre of what Harvard’s Doctor Eric Feigl-Ding has declared “an inevitable global pandemic”.

On the deserted streets below soldiers file by, accompanied by doctors and nurses recruited from across China – but like the liquidators of Chernobyl, these brave volunteers may never return home.

The foreboding scenes from inside Wuhan and landlocked Hubei province have trickled out through the social media site Weibo. The platform is awash with harrowing images of people collapsing in the streets, some dead, their bodies collected by patrolling medics in hazmat suits and gas masks. For Hong Kong’s apprehensive populace 550 miles to the south, it’s a waiting game.

As of Tuesday, Chinese health authorities had reported 20,438 confirmed cases and 425 deaths. Hong Kong also announced its first victim of the disease, a 39-year-old man who had returned from Wuhan. The sense of unease in the city is intensifying; if the virus gains a foothold in Hong Kong, one of the most densely populated countries in the world, home to tightly packed subway train carriages and millions living cheek by jowl in its notoriously tiny apartments, the conditions are more than ideal for the pathogen to spread rapidly

Today there are no people on the street, just signs saying, ‘keep five metres apart’. But the traffic lights keep changing, no matter what is happening in the world

The international travel hub is particularly vulnerable due to its connection to China through multiple border crossings by air, road, sea and rail. On Monday, Hong Kong’s leader Carrie Lam announced that 10 out of the 13 border crossings with mainland China have been closed, in a bid to curb the spread of coronavirus. Demand for complete closure of that border is coming from both pro-Beijing and pro-democracy supporters in a rare show of unity.

Many Hong Kongers who formerly opposed the pro-democracy movement have had their sentiments altered after witnessing the government’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak; particularly Chief Executive Lam’s reticence to take control. The need for greater autonomy from China now seems justifiable even to former critics, the threat of the encroaching pathogen quickly unravelling Beijing’s “one country, two systems” principle and the argument for greater self-determination evolving from one of ideology to one of survival.

Halting freedom of movement from the mainland would be a first for the territory since Britain handed it back to China in 1997, but the consequences this time could be severe. Hong Kong maintains a separate financial and legal system, but is still heavily reliant on the mainland for trade, labour markets, 80 to 90 per cent of essential goods, and all of its water supply.

A colleague has gotten worse, her fever has not gone down at all, she will need the strength of her own immunity to win this battle, God please bless my friend

Earlier this week Terence Chong, a professor of economics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said closing the border completely would be an overreaction akin to “shutting down the stock market”. But with the World Health Organisation (WHO) declaring a global public health emergency and international governments barring entry to travellers from China, Hong Kong risks being quarantined, perhaps even locked down, as has been the case for Wuhan. China has so far quarantined 16 major cities in an attempt to contain the outbreak, halting the movement of an estimated 46 million people

On the mainland, those who avoided getting trapped in Wuhan have been placed under quarantine in their own homes. Zhang Lin, a producer with online news platform Pear Video, and his brother Chao Lin were met by masked members of Tianhe District Residents Committee when they returned to Guangzhou from the town of Xianning, within the lockdown zone. They were ordered to remain indoors and report their temperatures to authorities via text every two hours. Six days into their quarantine and neither Zhang nor his brother have exhibited any symptoms. Zhang described his “fear of the unknown” and being “hyper-vigilant, looking for signs of the virus in ourselves, and in each other, wondering which one of us is infected, like that famous scene in John Carpenter’s The Thing.”

Transmission without symptoms is a characteristic that makes coronavirus more contagious than Sars (severe acute respiratory syndrome), which also originated in central China and caused nearly 800 deaths across the world in 2003. It is this trait that has left many questioning the usefulness of installing temperature screening in ports and doctors predicting the number of infected to swell to six figures by the end of next week.

A paper in The Lancet described a 10-year-old boy “shedding the virus and infecting others without showing symptoms”. This startling development was corroborated by Guangfa Wang, a respiratory specialist from Beijing, who despite taking every precaution when he visited Wuhan still became infected. Hours before the distinctive fever hit, he suddenly came down with conjunctivitis; this led him to conclude that the virus is transmittable through the eyes and advise the use of goggles as well as face masks, further taxing China’s dwindling supplies of protective gear. Isolation, it seems, is the only defence against infection.

From total lockdown in Hubei province to mandatory home quarantines in Guangzhou, China’s authoritarian regime seems equipped to implement the large scale measures necessary to stop the pathogen in its tracks. But as the world enters phase two of the outbreak – human-to-human transmission beyond China’s borders – the organisational skills of liberal nations that value freedom of the individual over the collective good will surely be tested.

The decision to “temporarily” close some of Hong Kong’s borders with the mainland and stop issuing travel permits to Chinese tourists as the death toll surpassed 130 came from an unlikely source – not from Lam, but her Chinese counterpart Luo Huining. Professor Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute, suggests the partial closure of the border was fabricated to look as though China came up with the decision, to reinforce Beijing as having the final say. Pro-democracy protestors have declared Chief Executive Lam’s handling of the outbreak as evidence that her government is a puppet of the mainland, pointing to the lack of transparency from Beijing as an indictment against authoritarian rule.

Alicia Garcia Herrero, of the international economics thinktank Bruegel, foresees that the Chinese government will never allow Hong Kong to completely shut its borders “as this would lead other foreign countries to immediately follow suit by closing their borders with China, with huge economic and reputational losses for Beijing”. Everything that has unfolded since the contagion broke, from the arrest of the whistleblowers who first brought attention to the seriousness of the pathogen on Weibo, to the CCP’s cloak of secrecy and the hiding of data from the WHO, is seen as a validation of the pro-democracy movement.

The truth of what is happening here is being twisted and changed by official lies instantly. If you are not living in this mess it is hard to imagine. Today people are trying to defend the eight whistleblowers of the coronavirus, the ones who got arrested for spreading ‘rumours’ at the beginning of it all. But the online propaganda machine will say, ‘they got arrested because they lied

The swift crackdown on those who tried to raise the alarm at the beginning of the outbreak shows that China’s old habits die hard. Doctor Li Wenliang, one of eight people reprimanded by Wuhan’s Public Security Bureau for “spreading rumours” about an “untrue” outbreak of coronavirus, posted on his Weibo profile at the weekend that he is now in intensive care after contracting the virus he tried to warn others against. His parents, also infected, are being treated in the same ward.

While China’s Supreme People’s Court defended its chastisement of the young doctor – Wenliang had thought the new pneumonia was another Sars episode – it fell short of praising his early detection, but did admit that “if the public had listened to this rumour at the time, it would have been a better way to prevent and control” the outbreak.

Joshua Wong, secretary general of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy group Demosisto, tweeted: “We are all terrified because this new virus reminds us of how the Chinese government covered up the severity of Sars … During the initial stages of the outbreak, the Chinese government concealed information from the public, limiting mitigation efforts and exacerbating the spread of Sars.”

But these fears underestimate how the infection could progress over the next few weeks, as Doctor Feigl-Ding said: “The coronavirus mutates extremely fast, is spread even by those who don’t show symptoms and is a higher pandemic risk than Sars. A groundswell of data all point to an impending global pandemic and I predict the number of those infected will soar to five figures over the weekend, and six figures in the next two weeks and worldwide.”

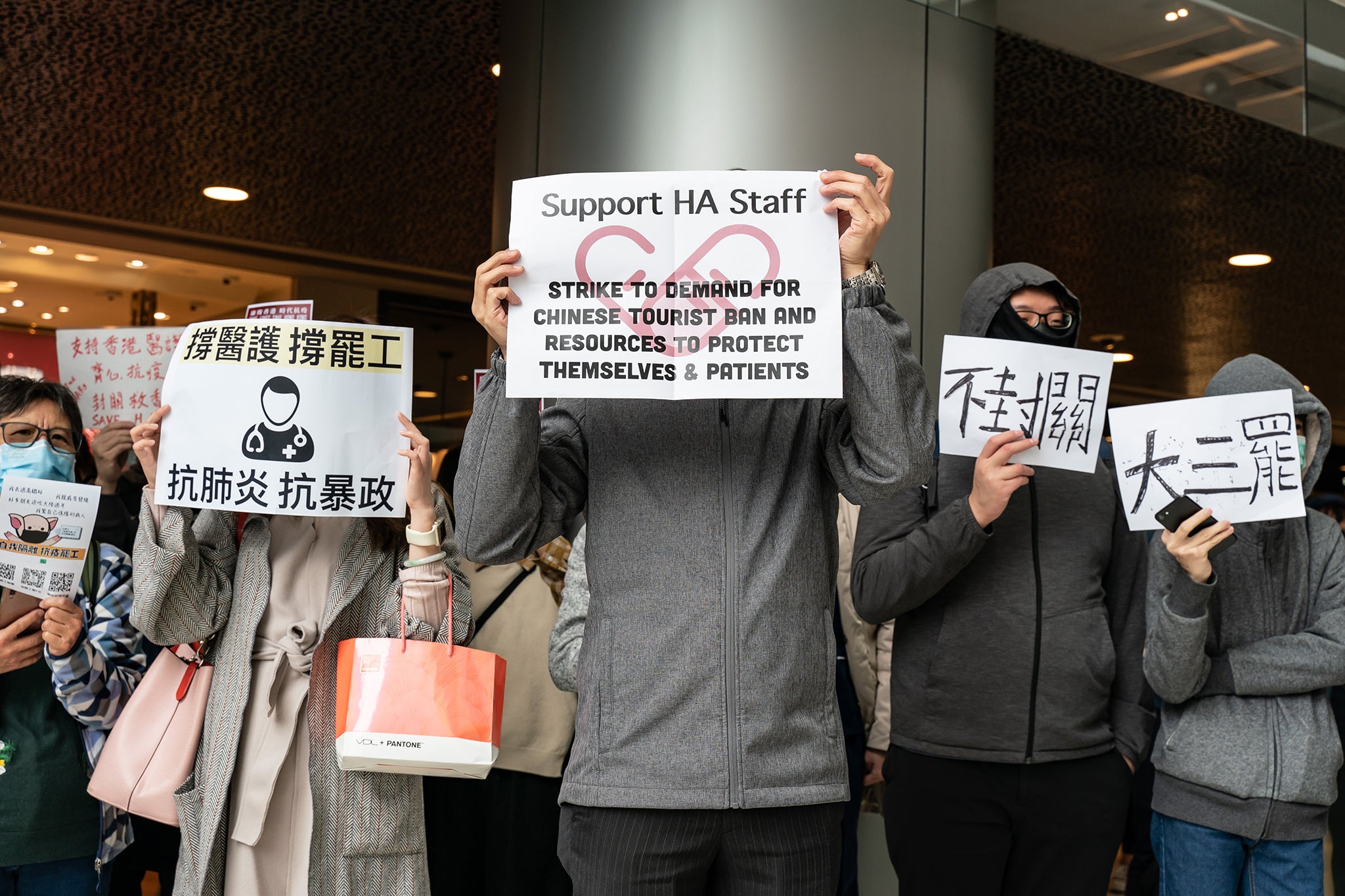

The Hospital Authority Employees Alliance, a trade union representing a large proportion of medical workers in Hong Kong, has declared that Lam’s partial closure of ports of entry is not enough and has voted overwhelmingly to start a five-day strike beginning Monday in order to pressure the government to completely close all crossings to mainland China. The union said it refuses to be “silenced and watch the innocent Hong Kong citizens becoming infected”.

The action to partially close the border is widely seen as cosmetic, as Hong Kong immigration department data suggests the government’s plan will only affect six China-to-Hong Kong crossings, which handle less than 9 per cent of passenger flow. But the strike may have had some effect and leveraged Lam to schedule more border closures, although she maintains that airports and the Shenzhen Bay and Hong Kong Macau bridges will remain open to traffic flow from the mainland. In a press conference on Tuesday Chief Executive Lam slammed the strike as disrupting “critical operations” during a time of great crisis for the city.

On Monday, Eric Lee, a doctor who spent the night queuing to sign up for the union before the strike ballot, was adamant that if the government did not acquiesce to the union’s demands – to ban the influx of infected people from mainland China – “Hong Kong would be overwhelmed, we would not be able to handle this influx from mainland China, as we are a high density city”.

Pharmacies all had their doors shut, posters displayed said, ‘masks, disinfectants, thermometers, all sold out

He added: “I don’t think the measures the Hong Kong government are implementing against the coronavirus that were announced by Carrie Lam are effective, I don’t have confidence in them at all.” Fellow doctor Ma Chung Yee also supports the strike, saying: “No one wants to go on strike. We all have a common goal, to pressure the government to implement strict border controls immediately.”

Fear of infection has exacerbated old animosities and suspicions towards mainlanders. In the labyrinthine streets of the Mong Kok district a poster lit by a flickering neon light outside a restaurant reads: “We don’t serve any people from any Chinese provinces until further notice.” Another warns: “No Chinese visitors, send them back straight away.”

Last weekend black-clad protestors in Fanling district tossed Molotov cocktails into the lobby of an apartment block earmarked as a quarantine zone for coronavirus patients. Locals, fearing the area could be used as overflow for overwhelmed Wuhan hospitals, however, praised the move.

One tells me: “We are talking about thousands of people being easily infected as 50 metres away there is a school. The puppet Hong Kong government has many means to stop the outbreak, like closing the border, but they just won’t do it. They’d rather risk healthy Hong Kong lives by taking in the infected patients from China.”

Another local resident, wishing to remain anonymous, says the atmosphere has changed politically in Hong Kong. “People do not have any confidence in the Hong Kong government, even the pro-Beijing people [known as the blue ribbons]. They also blame Carrie Lam for certain incompetent policies dealing with the coronavirus.

“The people protesting in Fanling two days ago against the quarantine site are not only pro-democratic people, but also the people who used to be pro-Beijing, and now people have ironically joked that the coronavirus has connected both groups, who have been split for eight months due to political reasons.”

Local news reporter Rachel Cheung echoes the sentiments, claiming on Twitter that “this is why locals are livid. They’re asking to implement infection control measures and close the border, but the government does the opposite, offering free treatment to mainlanders, with taxpayers’ money, and putting more pressure on the healthcare system, which is already under strain.”

But Zhang Lin, still in quarantine in his brother’s Guangzhou apartment, contests this claim. He argues that “Hong Kong’s infrastructure is aided and supported by China, so Hong Kong people have an obligation to treat mainlanders. No matter how precious Hong Kong’s medical personnel are, life on the mainland.is also precious.”

Today was such a sunny day, the golden sun was shining on the empty asphalt road, reflecting the dazzling life, I suddenly felt relieved

It’s clear that the unanticipated unity between Hong Kong’s opposing pro-democracy and pro-Beijing sides is one derived of fear rather than ideology. And that fear has given rise to a deeper, uglier contempt; the long-held animosity towards the mainlander, or the “ethnic other”. Only now, the “creeping invasion” carries a deadly contagion.

The coronavirus has tossed the cards of Hong Kong’s fragile political factions asunder, enough to make Carrie Lam vex over how they land in its aftermath.

Quotes from the diary of a boy trapped inside Wuhan, translated by Hong Kong artist Badiucao, have been included in this piece

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments