Covid intelligence: Who was responsible for the cyber-attacks on China?

Donald Trump is not alone in having suspicions about China’s involvement with coronavirus: Vietnam and Israel have questions too, writes Kim Sengupta

The cyber-attacks were aimed at China’s Ministry of Emergency Management (MoEM) and the provincial government of Wuhan. The aim was to collect information about coronavirus, a disease about which little was known at the time – its origins and its impact shrouded in mystery. This was not, however, the work of the US, British or other western intelligence agencies whose operations are now under focus, with Donald Trump, his administration and Republicans in Congress embarked on a policy of charging Beijing for the spread of the lethal pandemic and threatening severe consequences.

The spear phishing campaign was run by an espionage group called Ocean Lotus, also known as APT (Advanced Persistent Threat) 32 which, it is widely held in security circles, is linked to Vietnamese state intelligence. It has, in that capacity, targeted a number of foreign governments, private companies and individuals, according to research carried out by the US cybersecurity firm FireEye and other analysts.

APT32 seems to have become particularly active in China in the recent past. It began to be particularly busy from 6 January when it sent an email to Beijing’s MoEM using the sender address lijanxiang1870@163. This was two weeks before the Chinese government admitted that the disease could be transmitted between humans. “These attacks speak of the virus being an intelligence priority. Everyone is throwing everything they’ve got at it, and APT32 is what Vietnam has,” said Ben Read, senior manager at FireEye’s intelligence unit.

The Vietnamese connection provides an illustration of the role played by intelligence services in a number of countries, and their proxy cyber operatives over the contagion, ranging from trying to trace its history and spreading disinformation to finding and securing vital supplies of equipment to counter the disease.

As death tolls around the world from Covid-19 rise to more than 270,000, Vietnam, which shares a 1,100 kilometre border with China, has just 288 cases of Covid-19 with 241 recoveries from them and zero deaths. Even if one views these figures with a degree of caution, international analysts acknowledge that Vietnam has been remarkably successful in comparison with so many other wealthier countries with vastly more resources.

At the end of January, during the Tet New Year celebrations, Vietnam’s government said it was “declaring war” on coronavirus. At that time the outbreak was then officially confined just to China and it’s government had just began imposing quarantine and tracing of people who may have come into contact with the virus.

Vietnam imposed stringent restrictions earlier than Beijing, with the country’s prime minister telling a meeting of the ruling communist party that the disease would soon reach the country, with devastating consequences unless action was taken. “Let us have no illusions, fighting this epidemic means fighting the enemy,” said Nguyen Xuan Phuc.

It imposed a series of international travel bans, against the advice of the World Health Organisation (WHO), the compulsory wearing of face masks, rigorous testing and put tens of thousands in isolation. A key reason for Vietnam’s ability to keep the pandemic under control was advanced intelligence. This is a reflection of the lessons the country has learned through decades of military strife. The Vietnamese did not depend purely on their undoubted fighting skills to drive off the French, Japanese and American forces from their homeland, as well as repel Chinese incursion. They had to build an intelligence system over the years to achieve success against often overwhelming odds.

The Vietnamese government insists that claims of its links with Ocean Lotus is just “speculation”. But a former senior Vietnamese official who now lives in France reflects: “We have an unfortunate history of facing invasions as you know, so we have had to learn how to survive.

“We have learned to look out for threats, whether it’s from man or from nature, and take action. We are not a rich country, so we have had to act fast on information to protect our people and our economy. Our people are also used to hardship, so they accept the rules. Even people who do not agree with the politics [of the government] accept that they had to act quickly.”

The United States greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency. It will all work out well. In particular, on behalf of the American people, I want to thank President Xi

There were, as we know, other intelligence services which had been tracking the rise of coronavirus. And Beijing’s role in the spread of the contagion is now a key political issue internationally and domestically. Trump has suspended US funding of WHO because of its alleged collusion in subterfuge with Beijing and threatened new sanctions against China. Republicans in Congress have demanded reparations. Around 10 legal actions have started against the Chinese government, six of them in the US, including two by the states of Mississippi and Missouri.

Domestically, the question raised is when governments knew about the threat of Covid-19 reaching their countries — from WHO, the Chinese government and also their diplomats and intelligence agencies. Answers to these would have helped governments decide when to take measures like lockdowns, and also obtain crucial PPE, ventilators and other medical supplies to deal with the infection.

This is of particular importance in the US, with Trump heading for an election, a relentlessly rising death toll, and his own popularity falling and, to a lesser extent, in the UK where Boris Johnson’s government was one of the last countries to enforce lockdown in Europe, and now has the highest death toll in the continent.

The US administration is seeking two conclusions from its security and intelligence agencies. One is that China initially hid the outbreak of coronavirus from the outside world, a fatal delay with devastating consequences; persecuted doctors and other whistle-blowers who tried to warn of the contagion; destroyed evidence about the start of the disease and carried out a systematic misinformation campaign to claim that US forces planted the virus in Wuhan, and/or it originated in Europe or the US.

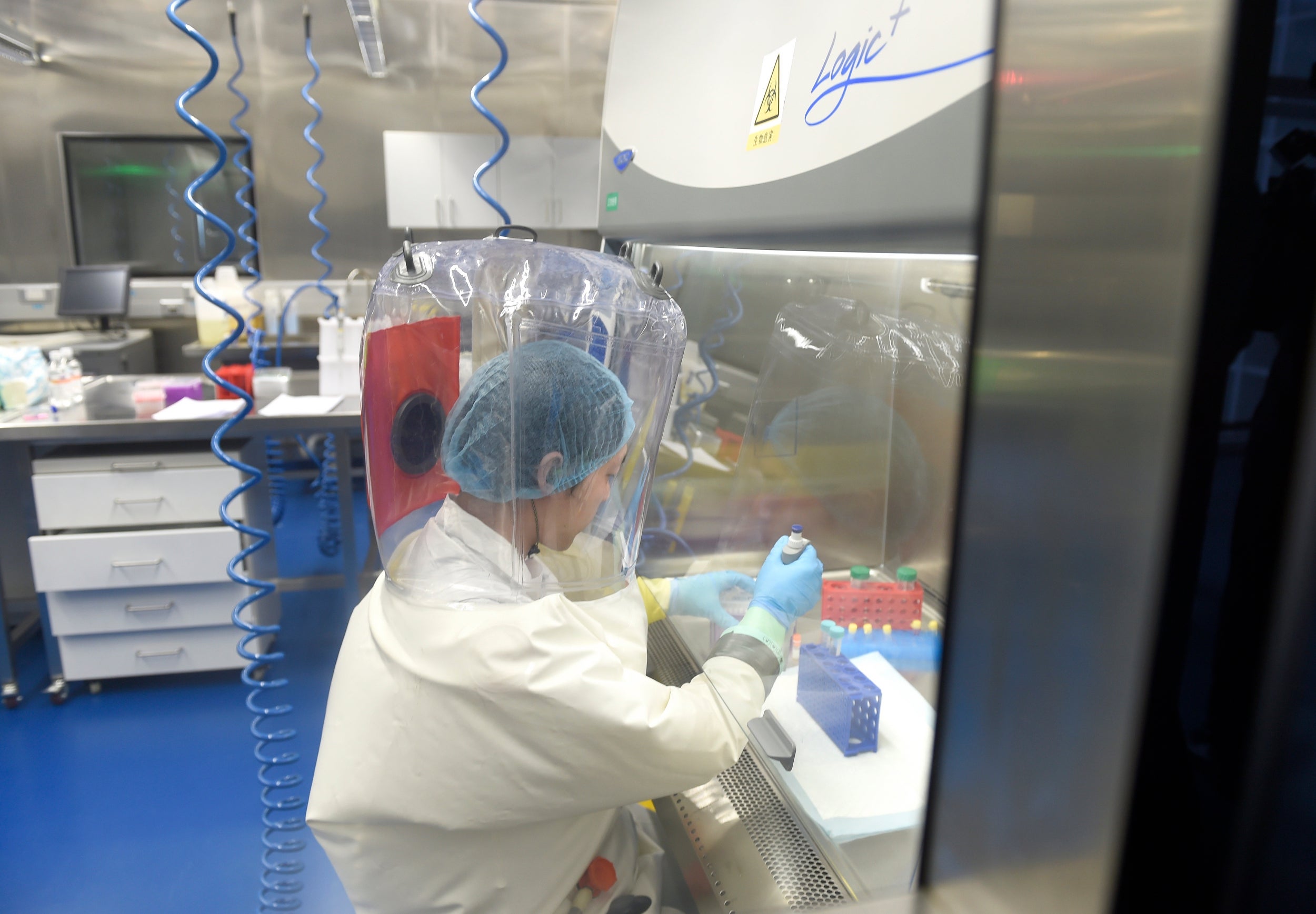

The second is that coronavirus is human-made, specifically at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. This has been the recent mantra from the administration. Trump claimed last week that he had evidence which gave him a “high degree of confidence” that the virus began at the lab. But he claimed that he was not privy to share that evidence. “I can’t tell you that. I am not allowed to tell you that,” he insisted.

Mike Pompeo claimed on Sunday that the evidence about Covid-19 originating in the laboratory was “enormous”, but again failed to provide it. The US secretary of state told the TV programme ABC This Week “there is enormous evidence that that’s where this began ... I can tell you that there is a significant amount of evidence that this came from that laboratory in Wuhan ... Look the best experts so far seem to think it was manmade. I have no reason to disbelieve that at this point.”

Hours before Trump’s allegations, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence had issued a statement stating there was no proof that the virus was manufactured. It said “the Intelligence Community concurs with the wide scientific consensus that the Covid-19 virus was not man-made or genetically modified.” Reminded of the formal statement by US intelligence contradicting the lab theory, Pompeo’s response was “That’s right, I agree with that.” On the same day, in an interview with Newsradio 1040, he said “we don’t know if it came from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. We don’t know if it emanated from the wet market or yet some other place. We don’t know these answers.”

Exactly when US intelligence services started looking at coronavirus remains unclear. There were reports that the National Centre for Medical Intelligence, a branch of the Defence Intelligence Agency, was alerted to a new virus spreading through Wuhan last November. The Pentagon denied this. However a number of officials, American and British, say information was being collated in December and documents prepared by January. The vice-chair of the US Joint Chiefs of staff, John Hyten, has confirmed that he saw reports early that month.

A serving Mossad operative, identified as ‘H’, was asked in an interview with Israel’s Channel 12 TV about the means used in the mission and whether it involved theft. He replied: ‘We stole, but only a little’

According to a number of US media reports, Trump was told about the coronavirus threat on or around 3 January. He maintains that he only learned about the seriousness of the disease “just prior” to imposing travel restrictions on China on 2 February. He had described the disease as an “unforeseen problem” that “came out of nowhere”. Last Sunday the president tweeted that the US intelligence community “did NOT bring up the CoronaVirus subject matter until late into January” and that “they only spoke of the virus in a very non-threatening or matter-of-fact manner”.

What we do know is that from January, when intelligence reports about coronavirus were circulating in the administration, until the end of February, Trump was fulsome in his praise of China and its President Xi Jinping no fewer than 15 times.

On 24 January he tweeted: “China has been working very hard to contain the Coronavirus. The United States greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency. It will all work out well. In particular, on behalf of the American people, I want to thank President Xi!”

Then on 10 February, in an interview with Fox News: “I think China is very, you know, professionally run in the sense that they have everything under control. I really believe they are going to have it under control fairly soon. You know in April, supposedly, it dies with the hotter weather. And that’s a beautiful date to look forward to. But China, I can tell you, is working very hard.”

On 29 February, at a press conference: “China seems to be making tremendous progress. Their numbers are way down ... I think our relationship with China is very good. We just did a big trade deal. We’re starting on another trade deal with China – a very big one. And we’ve been working very closely. They’ve been talking to our people, we’ve been talking to their people, having to do with the virus.”

Democrat presidential candidate Joe Biden’s team has made a powerful television add with a compilation of Trump’s praise of President Xi: embarrassing viewing for Republicans. Is Trump’s embrace of the Chinese government and inaction in dealing with the crisis the driving reason behind the push for the virus being made in the lab theory as a distraction?

There is, say security officials, enough intelligence about Chinese culpability in hiding the start of the virus, suppressing dissent and destroying evidence without insisting, and with no supportive evidence, that Covid-19 was made in a lab. Even now, the officials point out, the Chinese government is refusing to allow an international investigation and they are still refusing to share live samples of the disease with scientists abroad.

A Whitehall official says: “Wuhan is an American show. We have not seen any actionable intelligence that coronavirus came from a lab. We are keeping an open mind, there may have been an accidental leak from a lab, but we haven’t seen this yet. The UK government is fully aware of information received. Individual countries will use intelligence in individual ways.”

Israel’s use of its intelligence service, Mossad, is noteworthy in not so much tracing the origins of coronavirus, but actions after the arrival of the pandemic, as well as the surprising amount of publicity about the organisation. Mossad’s main task, it is said, was to secure supplies needed to counter the disease from around the world while other countries were also scrambling to do so. And it achieved this, using methods both legal and illegal.

The Israeli media reported that Mossad’s chief, Yossi Cohen, had set up a task force with a command centre in close liaison with the Israeli health ministry. His service, it is claimed, secured 10 million face masks, tens of thousands of test kits and dozens of ventilators by the end of March. Some of these came from Gulf states with which Israel does not have official diplomatic relations, but close security ties.

A serving Mossad operative, identified as “H”, was asked in an interview with Israel’s Channel 12 TV, about the means used in the mission and whether it involved theft. He replied: “We stole, but only a little.”

Not everything went according to plan. Medical goods obtained for Israel in Germany and India, two countries with which the Jewish state has strong relations, had to be abandoned after authorities there intervened.

The deputy health ministry complained that some of the kits brought by Mossad were not particularly useful. “Unfortunately what has arrived at the moment is not exactly what we are missing. The test is comprised of many components and the main problem is that we are missing swabs,” he said. There was also criticism that Mossad was trading on its myth. In Haaretz newspaper, writers Yossi Melman and Don Raviv complained of “exaggerated tales of Jewish 007s craftily smuggling goods to their country’s hospitals”. Former officers, said the article, “worry that their erstwhile colleagues will be thought of as cold-hearted thieves in the medical black market. They are also concerned that spurious missions of this kind, motivated by domestic politics, could distract from the vital authentic and perpetual duties of Israel’s secret warriors.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments