From marooned mutineers to Anne Frank: What can we learn from books about isolation?

William Cook chooses the tomes that might just help you through these tough times

How’s lockdown working out for you? I must admit it’s starting to get to me a bit. I know, I know – I’ve got it easy, a lot easier than most folk. My wife and kids are here at home and all we need to do is sit around, unlike all those key workers out there, risking their lives to keep us safe and comfy. Yet it feels a lot weirder than I thought it would. Is that how it seems to you?

Turns out isolation is no fun at all, especially if it’s something you haven’t chosen. Cyberspace is no substitute for real life. Skype is no substitute for meeting up face to face. My mum is on her own and it’s a month since I last saw her. I don’t know she’s coping. I know my situation is nothing special. I know that everyone else is going through the same sort of thing.

So what have you been doing to stay sane? I’ve been doing what I used to do to fill my days before the internet came along. I’ve been rummaging through my bookshelves, looking for old favourites to lift my spirits. I started off with a few upbeat titles, but funnily enough I soon found out it was the bleaker books that cheered me up – particularly books about isolation.

Of course it’s nice to be reminded that there’s always someone worse off than yourself, but there’s more to it than that. Isolation is a fundamental part of life, a perennial feature of human history, and though it’s been the source of much suffering, it’s produced some of the world’s best books.

In isolation we’re forced to confront ourselves and work out what really matters. I haven’t had any amazing revelations, apart from all the usual stuff (family and friends are precious, possessions aren’t so important) but these writers have achieved something else. In these ordeals, they’ve learned lessons that can be applied to every other part of life, even the strange netherworld we’re now living in. These books have helped me in bad times before, and in tough times today. Maybe they’ll help you too.

The Past is Myself by Christabel Bielenberg

In 1932 a well-to-do British debutante called Christabel Burton went to Hamburg to become an opera singer. There she met a dashing young lawyer called Peter Bielenberg and made a new life with him in Germany. When the Second World War began, and Peter went away to fight, she found herself alone in the Third Reich – a young woman from an enemy country, besieged by the air force of her native land. In 1944, as defeat drew near, Peter was implicated in the plot to assassinate Hitler and was sent to a concentration camp. In this inspiring book this brave, resourceful woman describes how, against all odds, she and her husband and their three children survived.

Serpent in Paradise by Dea Birkett

In 1789 the crew of HMS Bounty mutinied, cast their captain adrift in a small boat in mid Pacific and sailed to Pitcairn, an uncharted island less than two miles wide, 3,000 miles from the nearest landmass. Two hundred years later award-winning travel writer Dea Birkett hitched a ride on a cargo ship to see what had become of them. She found a place with no airstrip, harbour, roads or cars, and only a few dozen inhabitants, all descended from those mutineers and their Tahitian brides. Her brutally honest book reveals the price of isolation in a place where privacy is impossible, and shows what happens when a small group of people are cut off from the wider world.

Junky by William Burroughs

The deathly isolation of heroin addiction is described with cold and searing clarity by the author of Naked Lunch. By rights Junky should be a miserable book, a monotonous account of buying drugs, taking drugs, getting wasted and getting busted, but Burroughs’ prose is so spare and stark, and his ear for dialogue so acute, that this ruthless, dispassionate exposé is a compulsive and exhilarating read. “Junk is not, like alcohol or weed, a means to increased enjoyment of life,” he explains. “Junk is not a kick. It is a way of life.”

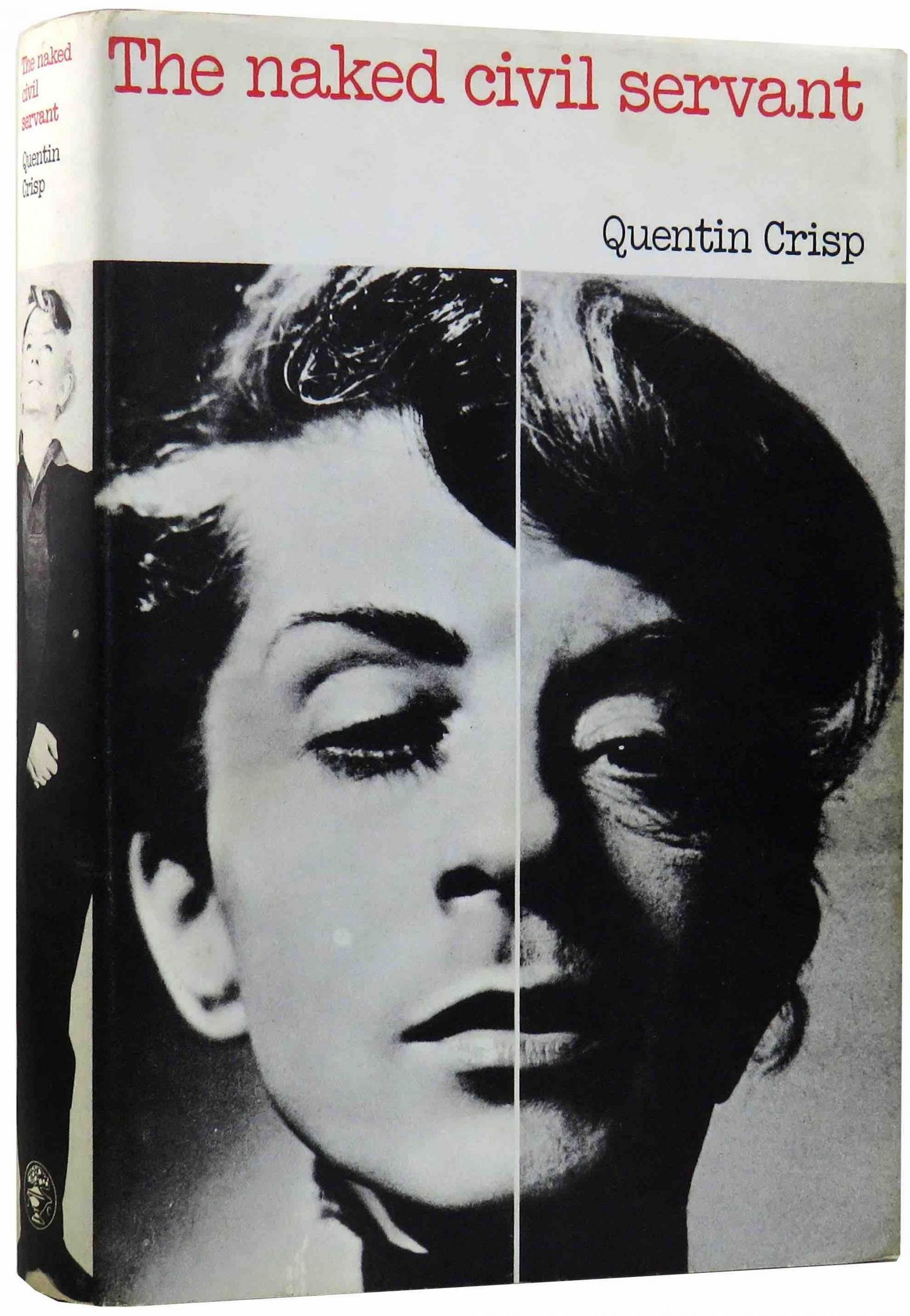

The Naked Civil Servant by Quentin Crisp

Crisp’s eloquent account of his life as an openly gay man – in an era when homosexuality was a criminal offence, and violent hostility towards gay men was routine – is rightly regarded as a landmark in the struggle for homosexual rights. However this book is even more than that. It’s a cri de coeur for eccentrics and individualists of every kind, a call to arms for anyone who’s ever felt ostracised or alone. Crisp recounts his lifelong refusal to conform with Wildean wit and a complete absence of self-pity, in a memoir whose abiding lesson is “above all, to thine own self be true”.

Down and Out by Wilfred De’Ath

A brilliant broadcaster with a bright future ahead of him, De’Ath’s life unravelled when he split up with his wife and ended up sleeping rough. His subsequent adventures as a gentleman tramp (and perennial jailbird) form the basis of this frank and funny book, culled from his long-running column in The Oldie. His fondness for checking into smart hotels and leaving without paying lands him in jail on numerous occasions. A habitual shoplifter and fare dodger, he fleeces various religious institutions, despite his devout Christian faith. De’Ath refuses to feel sorry for himself and offers no excuses for his bad behaviour, and his shocking yet entertaining memoir shines a bright light on a hidden hinterland of prisons, homeless hostels and seedy night shelters. Like Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, but with a lot more laughs.

Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe

Defoe’s first and finest novel is so much more than an adventure story for kids. Inspired by the true story of Alexander Selkirk, a Scottish sailor who was marooned on a desert island for several years, Defoe’s book isn’t merely a solitary survival manual. It’s about what becomes of us when everything we hold dear is stripped away. Three hundred years since it was written, this meditation on what makes a man is still just as relevant today.

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

Written in the attic apartment in Amsterdam where her Jewish family were hiding from the Nazis, and published after she perished in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, just a few months before the war’s end, Anne Frank’s teenage diary is a lasting testament to the power of the human spirt and a timeless memorial to one young life (and many millions more) cut short. “If only there were no other people in the world,” reads the last line of her diary, yet in spite of all its anxiety, the text is bursting with vitality and hope.

Stasiland by Anna Funder

How can you have any freedom in a land where you’re forever being spied on? How can your relationships have any meaning when anyone you speak to could be a spy? That was the world in which the inhabitants of the German “Democratic” Republic lived for 40 years, in which every citizen was a suspect. The Stasi was the secret police force which ran this nationwide surveillance operation, turning an entire country into a kind of open prison. In Stasiland, Australian author Anna Funder travels to the former East Germany to meet some of the oppressors and some of the blameless people they oppressed.

Modern Nature by Derek Jarman

“On 22 December 1986, finding I was body positive, I set myself a target: I would disclose my secret and survive Margaret Thatcher,” declared Derek Jarman in 1991. “I did. Now I have my sights on the millennium and a world where we are all equal before the law.” Sadly, Jarman didn’t live to see the millennium. He died in 1994, aged 52, of Aids-related complications, but in those few years he did a huge amount to tackle homophobia and prejudice against people with HIV. Painter, filmmaker, designer, campaigner, Jarman was also a fine writer, and his intimate, discursive diaries double as a kind of autobiography. Modern Nature is my favourite but the other volumes are just as good: Dancing Ledge, Kicking the Pricks and At Your Own Risk.

The Dark Room at Longwood by Jean-Paul Kauffmann

I’ve written about Kauffmann before, in The Independent and elsewhere, but the current crisis keeps bringing me back to him. Held hostage in Beirut for three years, this renowned French journalist has a profound understanding of isolation and suffering which offers us a unique sense of perspective in these troubled times. In this thoughtful, atmospheric book he sails to St Helena, one of the world’s most remote islands, where Napoleon was taken by the British after his final defeat at Waterloo and held captive until he died. Not just a travelogue, it’s also a moving meditation on memory, exile and death.

An Evil Cradling by Brian Keenan

In 1985 Irishman Brian Keenan left his lecturing job in Belfast and went to Beirut to take up a teaching post at the city’s university. After 15 years of virtual civil war, he fancied a change of scene. There he was kidnapped by Shia militiamen, who imprisoned him for four and a half years. An Evil Cradling tells the story of his incarceration, and his life-sustaining friendship with the British journalist John McCarthy, with whom he shared a cell, and endured enormous hardship. A harrowing yet ultimately uplifting book.

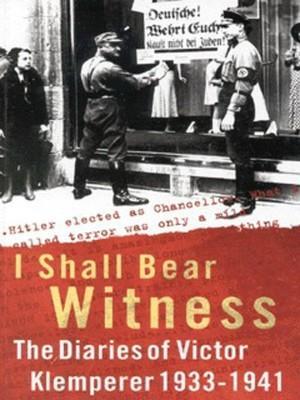

I Shall Bear Witness by Victor Klemperer

Klemperer was in his early fifties when the Nazis came to power, a minor academic at Dresden University, a German and a Jew. Throughout the Third Reich he kept a diary, chronicling Germany’s descent into madness and barbarity. What makes his account so absorbing is its focus on the details of daily life, showing how the Nazis gradually tightened their grip on every aspect of society, turning a civilised nation into a superstitious tyranny in a series of slow and steady steps. Klemperer was married to a German gentile and had fought for the Kaiser in the First World War. Because of this his deportation to the death camps was postponed until February 1945. Just as he was about to be deported the Allies bombed Dresden, reducing his hometown to rubble. In the ensuing chaos he escaped and fled. Klemperer returned to Dresden after the war, resumed his academic career, and died in 1960. His diary is a timely reminder that tyranny destroys democracy by stealth.

If This is a Man by Primo Levi

Born in Turin in 1919, Levi, an Italian Jew, was arrested in 1943 and taken to Auschwitz. His calm, meticulous account of his incarceration in that hellish place really ought to be unreadable, yet it’s impossible to put it down. How does he do it? It’s partly the quality of the writing – smooth and lucid, as clear as conversation. It’s partly his measured tone, which never curdles into rage or grief. But above all, it’s his belief in humanity, which survives every cruelty and depravity. Out of that darkness, he created a book that’s full of life.

Diary of a Man in Despair by Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen

Prussian aristocrat Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen was a popular novelist between the wars, but nowadays he’s best remembered for this erudite and heartfelt diary, which charts Germany’s moral degeneration under the Third Reich. His criticism of that murderous regime is astute, but what really distinguishes this book is its laconic tone of voice and its sardonic sense of humour. Arrested in 1944 and charged with “undermining the morale of the armed forces”, he escaped the guillotine, but was rearrested on a trumped-up charge and sent to Dachau concentration camp, where he died in February 1945, just a few months before the collapse of the tyranny he detested.

Taken on Trust by Terry Waite

After securing the release of numerous hostages in Iran, Libya and Lebanon, Terry Waite was kidnapped in Beirut, and held in solitary confinement for almost four years with no books, no pen or paper, and no news of the outside world.

During that incarceration he wrote an autobiography in his head, and when he was finally released, after nearly five years in captivity, he wrote it all down. In it he reveals three things that kept him going: no self-pity, no false sentiment and no regrets. “Living for years deprived of natural light, freedom of movement and companionship, I found that time took on a new meaning,” he says. “We all suffer. Many individuals have suffered so much more than I have. I am truly happy to have discovered that suffering need not destroy, it can be creative – if you read this book as a captive, take heart. Your spirit can never be chained.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments