Why do so many people believe in conspiracy theories?

Such talk is nothing new, but social media has provided a unique outlet at a time when our trust in those in power has plummeted, writes David Barnett

Once upon a time, conspiracy theories were, in the general consciousness, something of a joke. The phrase once conjured images of a social outcast sitting in their mum’s basement, wearing a tin-foil hat to ward off vague ideas of mind-control waves, and trying to prove that John F Kennedy had actually been shot by two different gunmen.

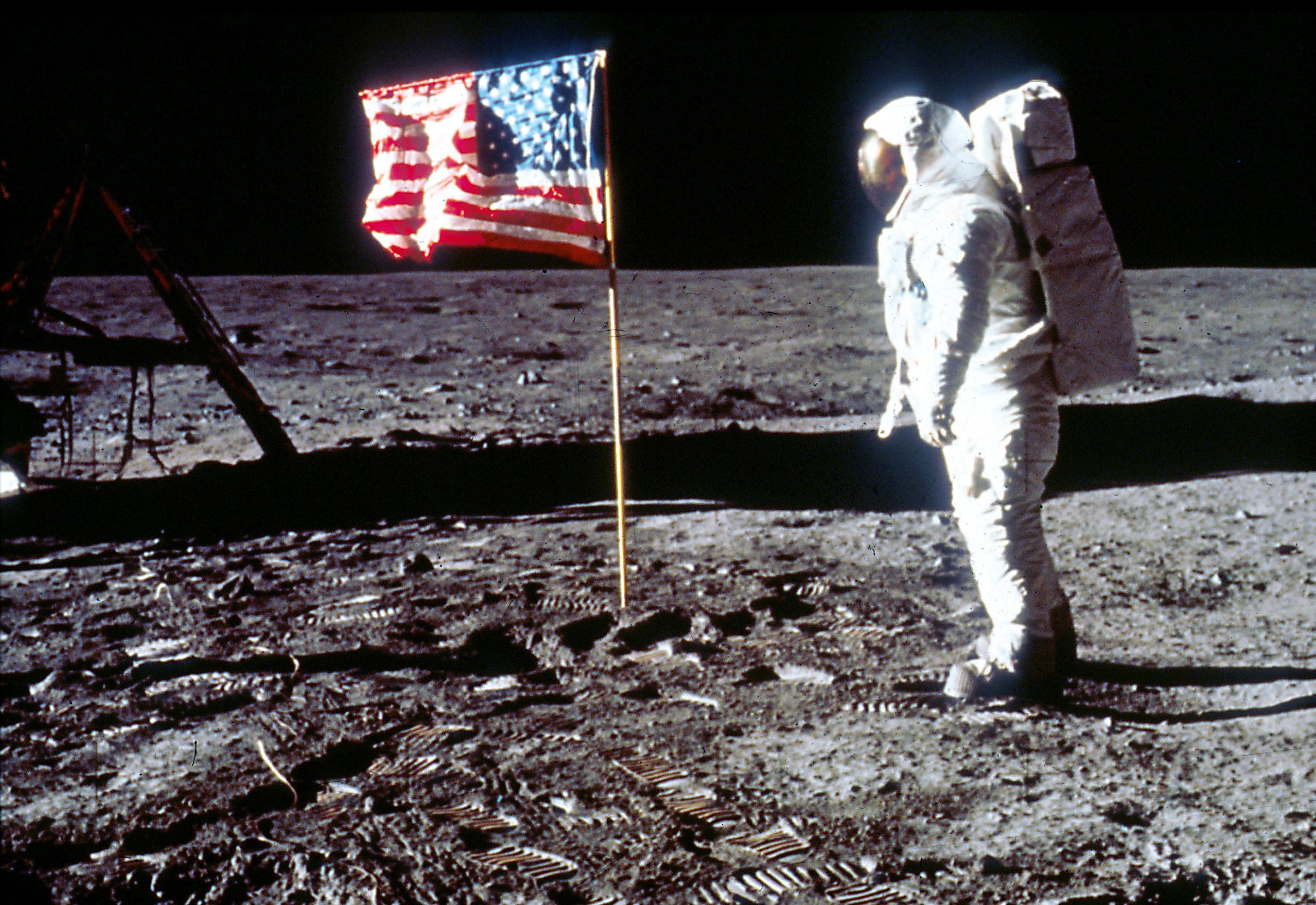

Popular conspiracy theories used to include things such as claims that the Apollo 11 moon landings of 1969 were faked by the US Government to artificially win the space race with Russia. Theorists pointed to the “fact” there were no stars in the sky in the photos, the American flag seemed to be rippling in the wind, of which there would be none on the Moon, and that the shadows of the astronauts were in the wrong place.

Then there are long-running conspiracy theories such as “the Illuminati” who some believe pull the strings of global governments. Back in 1975, Robert Anton Wilson and Michael Shea wrote their satirical science fiction trilogy The Illuminatus! which mapped a drug-fuelled story on the prevalent conspiracy theories of the day.

At the darker end of the spectrum, many people believe that the 9/11 destruction of the World Trade Centre in 2001 either never happened, or, variously, an inside job by the US Government.

In the last couple of years, however, the term “conspiracy theory” has taken on a slightly different tone, particularly since the Covid-19 pandemic.

The pandemic brought into play a hitherto unknown level of government intervention in our lives, alongside an unprecedented rapid-response vaccine development programme, and all played out for the very first time in the choppy waters of social media.

Information other than that provided by official sources abounded, and was amplified and shared at lightning speed. There’s an old saying that a lie can be halfway around the world before the truth has got its boots on, and that goes double in the age of social media.

Disquiet about Covid ranged from people who were concerned about the speed the Covid vaccine was rolled out, and how well tested it was – the “vaccine hesitant” – to those who believed Covid had been manufactured in a laboratory, to people who were concerned at the powers world governments granted themselves to essentially lockdown their countries and force the population to stay inside their homes.

Around this time, it felt there was a shift in the public perception of conspiracy theories. Everyone, of course, is entitled to their opinion, no matter how outlandish it might be. If you believe that Lord Lucan and Elvis assassinated JFK and escaped on Shergar (the racehorse stolen in 1983 and never seen again), then, well, that’s your outlook.

However, it is widely considered that questioning the official line during the Covid pandemic did actually prove harmful. Just months into the crisis, in August 2020, the World Health Organisation labelled the tsunami of online misinformation about Covid as an “Infodemic”.

“We’re not just battling the virus,” said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus at the time. “We’re also battling the trolls and conspiracy theorists that push misinformation and undermine the outbreak response.”

The fear was that such falseholds would put off people from getting the vaccine, Indeed, Covid created a division among the population that any true conspiracy could only dream of.

But whether Covid or the Moon landings or, as David Icke believes, that the Royal Family are in fact extra-dimensional humanoid lizards, why do we believe in conspiracy theories?

That’s a question Michael Shermer seeks to answer in his new book Conspiracy, out 30 November. Shermer is the publisher of Skeptic magazine in the US, which seeks to debunk claims and theories using science and rationality as its weapons.

According to Shermer, while the phrase “conspiracy theorist” might have gained a lot of traction during the pandemic, the idea is as old as the hills.

“There are no more conspiracy theories today than in the past, going all the way back to the founding of the Republic, or even back to ancient Rome,” He tells The Independent. “But their dissemination was through word of mouth and gossip, then through books, then newspapers, then radio, then television, all of which are glacially show compared to the internet, which can spread your conspiracy theory to millions in minutes.

“For decades, JFK conspiracy theorists met in tiny hotel conference rooms with a few dozen people, printed mimeographed newsletters and self-published books, and had few followers.

“Today, you can have millions of followers overnight, and even produce slick videos that are vastly more compelling than grainy newsletters. On the plus side, those of us who are interested in what is actually true can counter false beliefs just as fast using the same technology.”

But first, what exactly do we mean by a “conspiracy”? And just because we label something as such, does it necessarily mean it’s not true?

“A conspiracy is two or more people or an organisation plotting in secret to do something to a third party or another organisation to gain an illegal or immoral advantage or to gain power,” says Shermer. “A conspiracy theory is an explanation for events that involves the above. Some conspiracy theories are true, some are false, most are indeterminate.”

There’s a perfectly rational reason to mistrust authorities: enough of them really do conspire to do things to us that are illegal or immoral that it pays to assume the worst, just in case

Deciding which are true and which are fantasy is, he says, a “signal detection problem”. He offers the following logic trail to try to work out which is which:

A conspiracy theory is true and you identify it as such. Hit

A conspiracy theory is true and you fail to identify it as such. Miss

A conspiracy theory is false and you identify it as true. False positive

A conspiracy theory is false and you identify it as false. Correct rejection

Shermer says, “My argument is that we tend to make more ‘false positive’ errors, just in case. Better safe than sorry.”

And while “conspiracy theorist” was bandied about a lot in the past three years, the label goes back in its pejorative usage to really the 1950s and 1960s, especially in the wake of the Kennedy assassination in 1963.

“J Edgar Hoover and the FBI were keen to move the investigation away from a conspiracy to assassinate the President,” says Shermer. “Not because there really was a conspiracy but because the belief that there was one could trigger conflict with Cuba and the Russians, and the new President Johnson was eager to keep foreign relations calm.

“Before the Second World War, the term conspiracy theorist described most people because the belief in conspiracies was common knowledge and part of normal epistemology.

“Everyone ‘knew’ that big events like the First World War, the Great Depression, pandemics, presidential elections, and major congressional decisions were being manipulated by dark forces... the Illuminati, and the like.

“Conspiracies have always been mainstream. It was only post-Second World War that they were pushed to the margins of belief. I am trying to right that ship because there really are conspiracies and it is rational to assume that at least some conspiracy theories are true.”

“There’s a perfectly rational reason to mistrust authorities: enough of them really do conspire to do things to us that are illegal or immoral that it pays to assume the worst, just in case,” says Shermer. “It’s not an especially costly error to assume a conspiracy theory is true when it isn’t, whereas missing a real conspiracy against you could be very costly indeed.”

With the rise of social media especially, though, has come a distrust of the mainstream, and the turn towards unofficial news sources and commentators. One of the repeated cries from anti-vaccination or Covid deniers during the pandemic was “I’ve done my own research! Don’t trust the mainstream media!” Shermer calls this “disturbing”.

“The distrust of mainstream media, along with institutions of higher education, not to mention Congress and the presidency, is disturbing and, evidence shows, is worse now than before, and that is most certainly a result of social media fuelling divisiveness,” says Shermer.

He says that very often people will identify themselves with labels such as “investigator”, “researcher” or “independent scholar”, which marks them out from what he says are the trusted institutions of universities, respected newspapers or television news networks.

Shermer adds: “The problem for such independent thinkers is they are subject to all the same cognitive biases as those in mainstream institutions (my-side bias, confirmation bias, hindsight bias, etc.) without anyone reviewing their materials for fact-checking, quote confirmation, editing, etc.

“No one thinks that they’re wrong, or fringers, or pseudo-scholars, or pseudo-scientists, in the same way that no one in the history of the world believes they joined a cult—they joined a group that they believed would help make the world a better place (or improve their finances, or love life, or whatever). It’s only in hindsight that we recognise we were wrong.”

What Shermer’s book does is delve into the reasons why we are so ready to believe that, to borrow a phrase from perhaps the ultimate conspiracy theory work of culture, the X-Files: The Truth is Out There. And part of why we think that is because our levels of trust in those in power has plummeted in recent years.

People simply do not believe that our politicians, especially, are telling the truth. And if they don’t believe that, they will go to other sources to offer alternative schools of thought. And this, at its root is where conspiracy theories are born.

The answer, according to Shermer, is very simple. If everyone told the truth, and we all believed that was the case, there would be no need for conspiracy theories.

Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational, by Michael Shermer, is out on 30 November from John Hopkins University Press.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments