Comedy is an important tool in the fight against stereotypes – let’s not cancel it just yet

It’s natural to turn against old idols when we discover they have feet of clay, but cancellations and content warnings don’t work, says Eli Gottlieb. Making fun of human behaviour is the best way to change it

As Black Lives Matter protests sweep through US and European cities, many cultural icons are being erased from history or, as we now call it, “cancelled”. Statues of historical figures associated with colonialism and slavery are being toppled from their plinths, painted, burnt and thrown into rivers. Media companies are taking down popular films and TV programmes from their streaming services or qualifying them with disclaimers.

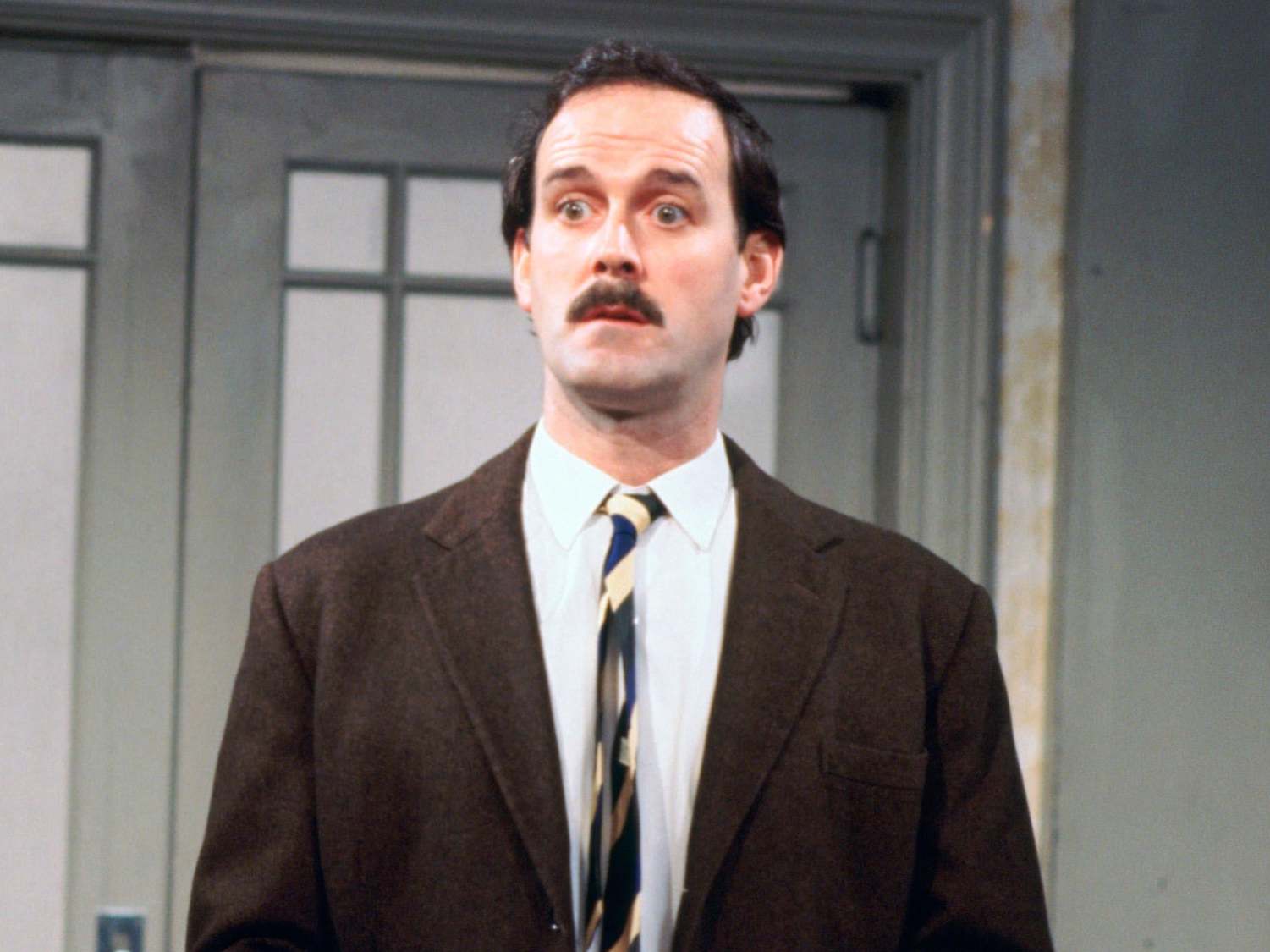

The BBC removed an episode of the 1975 comedy series Fawlty Towers from iPlayer and all three seasons of Little Britain, which first aired in 2003. The Jungle Book (1967) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) are now preceded on Sky Movies by a warning that the films contain “outdated attitudes, language and cultural depictions which may cause offence today”.

Iconoclasm – literally, image destruction – has an ancient history. It’s a theme that runs through rabbinic tales of Abraham smashing his father’s idols, destruction of Arabian deities in seventh-century Mecca and the sacking of churches by Puritans during the English Civil War. In more recent decades, we’ve seen mobs tearing down statues of deposed tyrants, from Lenin to Saddam, and Isis militants reducing ancient archaeological sites to rubble.

Whether Jews, Christians, Muslims or BLM activists, iconoclasts usually have similar motives: to remove an affront to their convictions, to assert their dominance over those they seek to overcome and to unleash repressed rage on inanimate objects.

All forms of iconoclasm, from the literal smashing of idols to the metaphorical cancelling of people and cultural artefacts, focus – by definition – on appearances. That’s not to belittle their significance. Symbols matter. Depictions of race that seemed acceptable in the past rightly offend us today. A monument to a slave trader in a public square makes that square less public; descendants of slaves own it less than descendants of slave owners.

But removing symbols of racism doesn’t remove racism. It changes how things look, not how things are.

Cancellation of TV programmes and movies rarely works. More often, it boomerangs. That was the case in recent weeks: media companies’ purges of offensive material only sharpened peoples’ appetite for it. For example, illegal downloads of Little Britain from pirate platforms surged in the days following its removal from iPlayer. And, predictably, conservative identity politicians grabbed their latest chance to portray “mainstream media” as peddlers of censorship.

Content warnings don’t work either. Recent psychological studies show that adding trigger warnings to texts and pictures makes little or no difference to how people experience them. In any case, such warnings are designed to protect the issuer, not the viewer. Sky’s warning, for example, neither protects viewers from offence nor places the movies’ depictions in historical context. It merely advertises the company’s own virtue and dodges responsibility for the movies’ content.

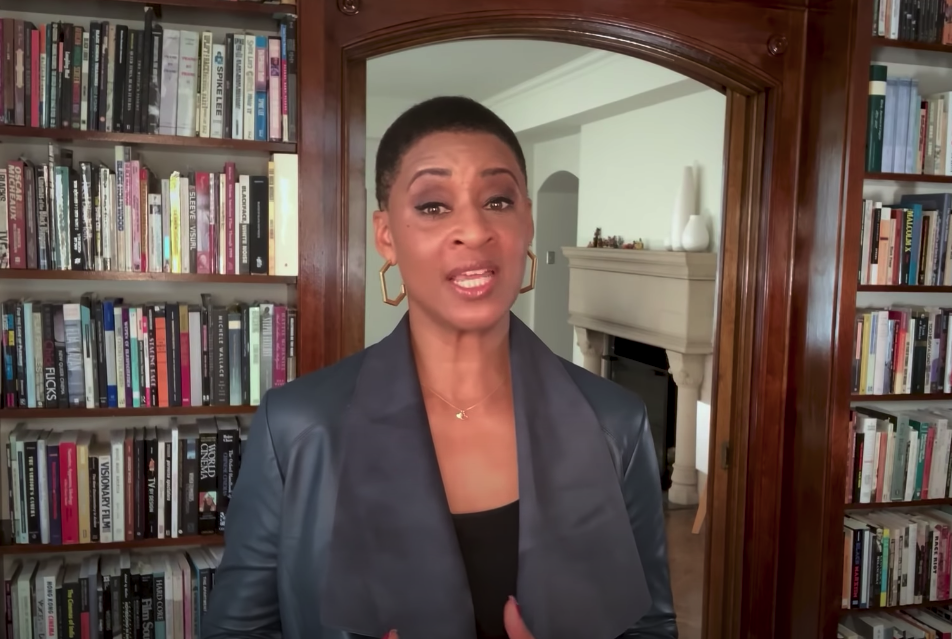

HBO Max is a notable exception. Following an LA Times op-ed suggesting the company remove Gone with the Wind (1939) from their website, they did exactly that. Two weeks later they made it available again. But this time it appeared alongside a panel discussion and a documentary placing the movie in historical context. Instead of dodging responsibility, the company used its platform to educate viewers.

Interestingly, media companies are being more forgiving of drama than comedy; while “problematic” dramas are being qualified with disclaimers, comedy shows are being removed completely. This is no coincidence. Comedy is the antithesis of correctness. Its power lies in holding up a mirror to our hypocrisies and reducing them to the absurd. Its play with stereotypes is itself a kind of iconoclasm. It takes down our idols and social certainties from their pedestals and shows them to us in all their silliness and human frailty.

Comedy is untameable. If the depictions of race, nationality and sexuality in Fawlty Towers and Little Britain still make people laugh 20 or 50 years after they were first broadcast, no warnings or explanatory documentaries can make them more “appropriate”.

In theory, everything is fair game for comedy. Quirks and strangeness intrigue us; exaggerated depictions of how we differ from each other release pent-up tensions that accrue from managing these differences in real life. Part of that release comes from laughing at others, not only with them.

In practice, however, rules of thumb have evolved to distinguish well-intentioned ridicule from deliberate aggression. One such rule is that you can make fun of your own group but not of others. Interestingly, this rule seems to be observed on a sliding scale: most strictly of all regarding race and ethnicity; less strictly regarding sexual orientation and physical features; even less strictly regarding nationality and social class; and not at all regarding gender (in the old-fashioned, binary sense of men making fun of women and women making fun of men).

It’s not clear why this sliding scale exists, or why it slides in this particular way. Perhaps it is related to the degree to which discrimination between different kinds of groups has led historically to violence; the degree to which mobility is possible between groups; or the degree to which differences between groups are visible. But none of these parameters explains why we are so much more accepting of men making fun of women than of white people making fun of black people.

Another feature of the rule is that it’s asymmetric. It’s more acceptable for black people to make fun of white people and for gay people to make fun of straight people than vice versa. This can be attributed to the history of oppression and the ongoing power differential. For white people to make fun of black people is to add insult to injury; for black people to make fun of white people is to fight the power.

Of all the comic shticks that break the rule, none is considered further beyond the pale today than blackface. So much so that it seems incomprehensible that only a few years ago such depictions appeared on television regularly without inciting even the slightest complaint, let alone general outrage.

Whatever our concerns about free expression, this is no time to be arguing the nuances of which kinds of blackface might be more or less acceptable. When the streets are burning with justified anger at the continued disregard for black life, it makes sense to remove the most blatantly offensive racial depictions and postpone such discussions indefinitely. As their creators’ acknowledge, this includes some of the sketches in Little Britain.

Nevertheless, it is a mistake to assume that when we laugh at stereotypical depictions we are laughing at those being stereotyped. More often, we are laughing at those doing the stereotyping. For example, we don’t laugh at Basil Fawlty’s German guests for taking offence at his Hitler impersonation. We laugh at the xenophobia and insensitivity that lead him to assume that they will enjoy it and to berate them for being humourless Krauts when it doesn’t.

Similarly, many of Little Britain’s funniest moments are those in which a character’s exaggerated political correctness is revealed to mask underlying prejudice and hypocrisy. When Linda, the college administrator, avoids identifying students as black or Asian but instead labels them with a long list of more offensive epithets, we laugh both at her racism and at the mess she makes trying to not to express it explicitly. When Daffyd, “the only gay in the village”, ties himself in knots of self-contradictory homophobia, we are not laughing at homosexuals or homosexuality but at the contradictions of wanting both to be accepted as normal and also recognised as different.

Laughing at racism doesn’t mean we don’t take it seriously. Scenes and characters like those above show casual bigotry for what it is: ingrained, harmful stupidity. Removing them from our screens diminishes our capacity for self-critique. It throws out the baby of social commentary with the racist bathwater.

Alternatively, the BBC could go one better than HBO Max. It could remove scenes with blackface, leave the series’ more subversive commentaries on race, gender, sexuality and disability, and add a filmed discussion with the series’ creators about what they removed and why.

The iconoclastic impulse is understandable. It’s natural to turn against old idols when we discover they have feet of clay. But when we lump together all comedy that contains racial stereotypes – regardless of whether it’s perpetuating or undermining them – we reduce diversity rather than protecting and celebrating it. To move beyond a world that casts everything in terms of black and white, we need all the nuance we can handle and every form of social critique that we have at our disposal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments