What do we really know about the trillions of bacteria we share our bodies with?

And can they help our understanding of human disease? Mick O’Hare speaks to scientists about the good bugs, the bad bugs and the new discoveries that make up our microbiome

It’s cold and flu time again. The scratchy throat, the sniffles and the irritating cough that leave us acutely aware that there is something living inside us.

Of course, most of the time we are oblivious to the fact that we are hosts to anything. The odd tummy bug or dose of athlete’s foot notwithstanding, most of the time we are unaware of anything invading our body space. Which is quite extraordinary, because humans are home to an astonishing array of species living both on us and in us. And while you’d think that we’d know pretty much all about the bugs, microbes and fungi that inhabit our body space, we don’t.

As recently as this decade, in 2013, researchers at the University of California and at Cornell University in New York discovered an entirely new phylum of gut bacteria, Melainabacteria, while only last year, simple single-celled organisms known as archaea were found in humans. These had previously only been seen to exist in extreme environments such as super-hot thermal springs, so their discovery in human noses and our appendixes was met with amazement.

What’s more, these new species are helping our understanding of human disease because researchers also discovered that, for example, people with fewer Melainabacteria in their intestines have a far greater risk of Parkinson’s disease. Could introducing Melainabacteria into human guts prevent or alleviate the condition?

More on how these new discoveries might be affecting our health later, but what is markedly apparent is that humans are home to more microbes and, indeed, larger organisms than perhaps we’d care to contemplate. The first person to outline the seriously huge numbers of species that inhabit us was bacteriologist Theodor Rosebury in his 1969 book Life on Man. Rosebury wrote: “If we are to get to the microscopic centre of this with our eyes open and our stomachs steady we might do better to look gingerly and sip instead of gulping… the life on man consists of microbes in extraordinary variety and large numbers.”

So the bald facts: the average human is home to trillions of microbes, with numerous contested estimates ranging from about 40 trillion to 100 trillion – it might even depend on the individual, but whatever it is it’s a huge number (100 trillion is 100 followed by 12 zeroes) all living on and in you

This likely outnumbers by far the 30 to 40 trillion cells from which you are made. Our skin has somewhere between 10 million and a billion bacteria per square centimetre while our intestines, where it’s warm, protected and full of nutrients, are home to more than 2,000 species or a whopping 10 billion bacteria per cubic centimetre… at least! Which means, of course, that every day a hell of a lot of them (as many as 100 billion) vanish down the toilet (don’t worry, they are replaced at a very rapid rate). And indeed you shouldn’t worry, because rather than being nasty invaders intent on making us ill in order for them to thrive, some of these microbes are beneficial to our health.

So what’s out there (or, indeed, in there)? What’s harmful? What’s benign? What’s actually helping us out? Well, there are some species that live on us that we can actually see, not all are microscopic – think head lice for example. So let’s do the grownups first. Not only do lice make a home in head hair, but they are also equally happy living in your armpits or pubic hair. Maybe depilation has its positives and is not just a passing body fad.

Antibiotics are blunt tools that kill more microbes than they are intended to. And they are increasingly ineffective. But if we can find a single organism that interacts with pathogens in our bodies and renders them harmless rather than dangerous, we can use our own microbiomes to help cure us

Fortunately, lice tend to be more itchy than health threatening – unlike ticks, which can cause any number of nasty and exotic diseases from royal farm virus (most people recover) to Omsk haemorrhagic fever (often deadly). And then there is the scabies mite, which is believed to infest millions of humans worldwide, and is able to burrow into the body to hide itself and its offspring, causing a nasty itch. Mites like humans. Some live in your eyelashes. Slug-like in shape, Demodex mites, a relative of spiders, are about half a millimetre long and store a lifetime of their own faeces in their bodies until they die, crumble and by entering our facial pores possibly cause the skin condition known as rosacea.

And then there are the ones that get inside us, such as 20-metre beef tapeworms or the Schistosoma worm, which can lead to a bloody and scarred bladder. Perhaps most horrifying of all, the brain can house Naegleria fowleri, an amoeba that loves the warmth inside your skull, reproducing in its millions until you drop dead. Lovely…

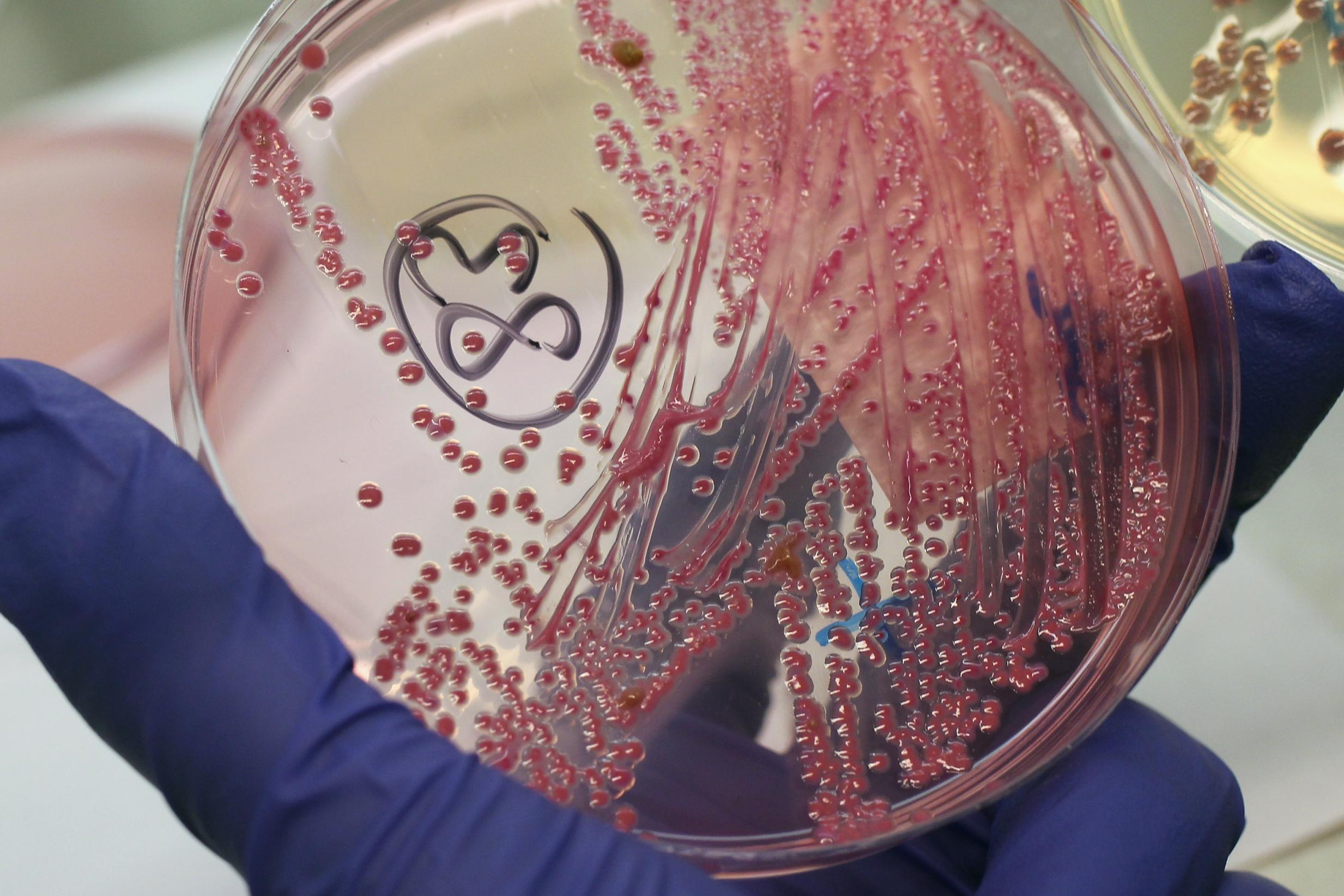

Of course, these animals account for a very small number of the species that live on and in us. It’s the tiny stuff, invisible to the naked eye, that makes up our microbiome – the aggregated collection of microspecies that inhabit us and now being picked apart and logged by the United States National Institutes of Health’s Human Microbiome Project (or HMP), essentially a census of what calls us home. It’s an enormous task, one which its director Francis Collins describes as akin to “15th century explorers describing the outline of a new continent”.

And it’s not just the bacteria that you might expect – fungus is, if you’ll forgive the pun, mushrooming pretty much everywhere. Everybody knows athlete’s foot is fungal (and maybe that it can also get into your genitals to give you what’s known as jock itch) but dandruff? Yes, those tiny slabs of falling skin that litter your shoulders on a bad day are caused by the Malassezia fungus, which feeds on oils produced in your scalp. The fungus excretes oleic acid, which dries out the skin that litters your collar.

Fungus grows in your conjunctiva, lungs and belly button – there’s even a Belly Button Biodiversity project run by North Carolina State University. Next time you get picking you should send them the products. And, of course, everybody has heard of the yeast Candida – yes, that’s a fungus – which can trigger infections in the genitals, mouth and in skin folds including under breasts and in the scrotum.

Viruses too take up space in our bodies. Despite our fears, most are harmless, others like herpes or papillomaviruses (of which there are more than 100 types in humans) may loiter for years, making themselves apparent every so often with nasty pustules such as cold sores or genital warts. It’s likely that 50 per cent of people reading this are infected

If we are to get to the microscopic centre of this with our eyes open and our stomachs steady we might do better to look gingerly and sip instead of gulping… the life on man consists of microbes in extraordinary variety and large numbers

And if you’ve ever had chickenpox (which most of us have) the shingles virus will be living in nerves near your spinal cord waiting to be triggered. It’s itchy and it hurts! But at least we know what shingles does, unlike the sequences of DNA that make up almost a tenth of our genome and consist of stretches of fossil viruses that infected our ancestors millions of years ago. These have the potential to mutate and cause new diseases we have yet to encounter.

But of course, the overwhelming constituent of our microbiome is bacteria, some good, some bad, mostly indifferent. And they really are everywhere: thousands of different species forming distinctive communities at hundreds of different body sites. There’s more on the inside than on the outside but nowhere is bacteria-free. The HMP has shown us that even areas we believed had no colonising life forms such as the uterus and biliary tract have their own coteries. Rosebury described human-dwelling bacteria as akin to a “teeming population during Christmas shopping”.

On the outside, every square centimetre is covered and although the number of species varies – oily skin on the nose, sweaty armpits or the anus will always have more than where there is liquid flow such as tear ducts or urinary tracts – even these sites are dwarfed by the number inside you. Your mouth contains hundreds of species while concentrations on your teeth and in your throat increase a thousandfold. Plaque is packed with them.

It might all sound very unpleasant but if you were to put all the bacteria on us and in us into a container the volume would perhaps be no more than one and a half kilograms of our total weight. Far more significant is what they do for us, for good or for evil.

Let’s look at some bad stuff first. It’s a minefield out there. Where do we start? Of course, there are plenty of bacteria that once in the stomach can cause sickness and diarrhoea, but around and in the nose we might encounter Staphylococcus aureus, which has a notorious antibiotic-resistant strain that causes MRSA, or another subspecies which causes pneumonia. Belly buttons can harbour Clostridium, a bacterial genus that can cause botulism and gangrene – a good enough reason to give it a regular cleanout – while Staphylococcus aureus found elsewhere on the body, especially in crevices such as the insides of elbows or the backs of knees, is possibly implicated in eczema.

There are more mysteries too on our insides, where maybe a thousand species of bacteria reside. The composition of our gut flora changes over time as we age and as we alter our diet. As you will have noted, not all your faeces smells the same. It seems that an overabundance or lack of certain species can lead to an increase in autoimmune or inflammatory disease. Fascinatingly, it would appear that an increase in the presence of certain species of firmicutes and fewer bacteroidetes can cause obesity (rather than obesity creating the varying populations)

It might all sound very unpleasant but if you were to put all the bacteria on us and in us into a container the volume would perhaps be no more than one and a half kilograms of our total weight. Far more significant is what they do for us, for good or for evil

It even seems that we need our gut bacteria to maintain a uniform personality. Stephen Collins of McMaster University in Ohio has found that mice with a sterile gut environment behave aggressively. When normal mouse gut bacteria is transferred to them their behaviour returns to normal. This could have implications for human behaviour too: humans with depression have been found to have higher than average amounts of coprococcus and dialister bacteria in their intestines. And it seems that people who go on to develop Alzheimer’s disease have higher proportions of the bacteria that causes gum disease: Porphyromonas gingivalis. More research, however, is required.

What’s almost certain is that when out of control, bacteria can cause cancer. Microorganisms generally are implicated in about a fifth of human cancers but bacteria especially is suspected in cancer of the colon and rectum where the disease is more common and bacterial density is greater than in the rest of the intestine. The exact mechanism is unknown, although species such as Helicobacter pylori cause an inflammatory response in the stomach leading to ulceration and possibly tumours, and tumours also occur at other sites on the body where bacterial density is significant, including the respiratory tract. Helicobacter pylori and other bacteria may also be implicated in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

And although it’s not especially deadly, the smell you get from your armpits after a long commute or a hearty gym session is caused by bacteria feeding on apocrine fluid released from sweat glands. Similar glands are found in our groins. Well indeed…

But that’s just focusing on the bad stuff and giving the bacteria that call our bodies home a negative press. Even pathogenic bacteria known to cause illness usually just coexist with their human hosts and only turn dangerous in extreme concentrations or if they stray to a different region of the body. Many others are our allies and some actively benefit us.

One bacterium, Propionibacterium acnes used to be implicated in acne because it was present at the site of facial spots and pimples. But now we know this species actually fights the presence of other bacteria that infect the follicle and instead reduces the level of infection. The presence of Lactobacillus in the vagina is also protective too. As well as fending off Candida albicans infections, babies born vaginally get a coating of Lactobacillus on their skin, which seemingly has a protective effect, possibly on the immune system, and may explain why babies born by caesarean section who receive their first bacterial encounters in the open environment are more likely to suffer from conditions such as eczema and asthma. Also linked to birth is the bacteria that lives in an unborn child’s placenta.

Kjersti Aagaaard of the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston has discovered that a mother’s diet changes the bacteria found in the placenta, probably transferred there by her bloodstream. This ties into other research that once seemed improbable which shows women with gum disease are more likely to have a premature birth. “If we could find out which bacteria are important for health, we could make sure they are there before birth,” surgeon James Kinross of Imperial College London told New Scientist.

It’s something increasing numbers of researchers are looking into, for adults as well as newborns. “I think we’re gaining more ground in terms of beneficial organisms on the human body and how we can use them to benefit our health,” says Karen Nelson, a team leader at the HMP. One example is the bacteria Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which helps counteract the misdirected immune response that damages the intestines of people with Crohn’s disease, while it’s believed that the human microbiome is responsible for mitigating against many other diseases such as type 2 diabetes, or helping to synthesise vitamins. The researchers at HMP have also discovered that if one useful bacteria in your body is suddenly not present, maybe from a dose of antibiotics, another one can take over its function. “Bacteria can pinch hit for each other,” says Curtis Huttenhower of the project.

But back to all the new stuff we’ve been discovering recently. Earlier this decade the team that discovered Melainabacteria also found microbes with surprisingly small genomes (or genetic material) living in human mouths, that elsewhere only lived in groundwater. Another group of researchers also found similar rare microbes in human mouths that were previously only known in peat bogs and river sediment. Their lack of genetic material almost suggested they were an entirely new form of life, one that needed a human mouth or other bacteria-rich host environment to survive because it required a symbiotic or parasitic relationship with other species. The University of California team, led by Jillian Banfield, placed the recently discovered organisms on a new evolutionary branch called Candidate Phyla Radiation or CPR. Later on, CPR organisms were also to be found in Neanderthal teeth.

But what are they doing in our mouths and the mouths of our ancestors? Well, although there has been excitement about their discovery, equally worryingly, they seem far more abundant in people with certain illnesses including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). And that’s because it seems, in the case of IBD, that one of these new CPR microbes can only grow on another bacterium called Actinomyces odontolyticus, which is also present in human mouths and can, if unchecked by our immune systems, cause IBD. The CPR microbe acts as a parasite and changes Actinomyces odontolyticus in a way that means our immune system can no longer detect it. Hence people with microbes of this particular CPR in their mouths are more likely to have IBD.

But it’s not all bad news. Xuesong He, a microbiologist at Forsyth University in Massachusetts, says that learning about these interactions between different organisms in our bodies could also work in our favour. “Antibiotics are blunt tools that kill more microbes than they are intended to,” he says. “And they are increasingly ineffective. But if we can find a single organism that interacts with pathogens in our bodies and renders them harmless rather than dangerous, we can use our own microbiomes to help cure us.”

Sadly, such treatment won’t be on-stream this autumn, unlike your runny nose. But after you’ve given it a good blow put aside your disgust and take a look at the teeming life right there in your tissue. Better out than in you might think and in the case of a cold virus you’re probably right but as Martin Blaser of the New York University School of Medicine heeds: “Don’t knock the microorganisms. I would hate to live without them.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments