Should citizens be allowed to patrol their own streets?

In an effort to stamp out knife crime, one London borough is using young people to police neighbourhoods. Wary of the vigilante label, Irena Barker asks if these groups are safe and effective?

University law student James is sitting at a table in the Walthamstow branch of McDonald’s. Rain pours down in the darkness outside. Slim and unassuming, the 20-year-old speaks in a soft voice as ambient music plays over the speaker system. “I’ve lived quite a sheltered life,” he says. “My parents made sure to stop me going to places where gangs were present.”

For much of his childhood, he was unaware of the extent of youth violence in the London borough of Waltham Forest where he grew up. “But then, around the beginning of sixth form, one of my friends was stabbed in the head,” he says. And this incident changed everything. At the age of 17, he and his friends became afraid to go out at night and enjoy themselves like normal teenagers.

Like much of London, Waltham Forest has been the scene of several high-profile teenage killings in the past few years, including the stabbing of 14-year-old Jaden Moodie in January last year. All this, says James, eventually led him to take part in a new council-commissioned initiative that uses young people themselves to help tackle youth crime and alienation.

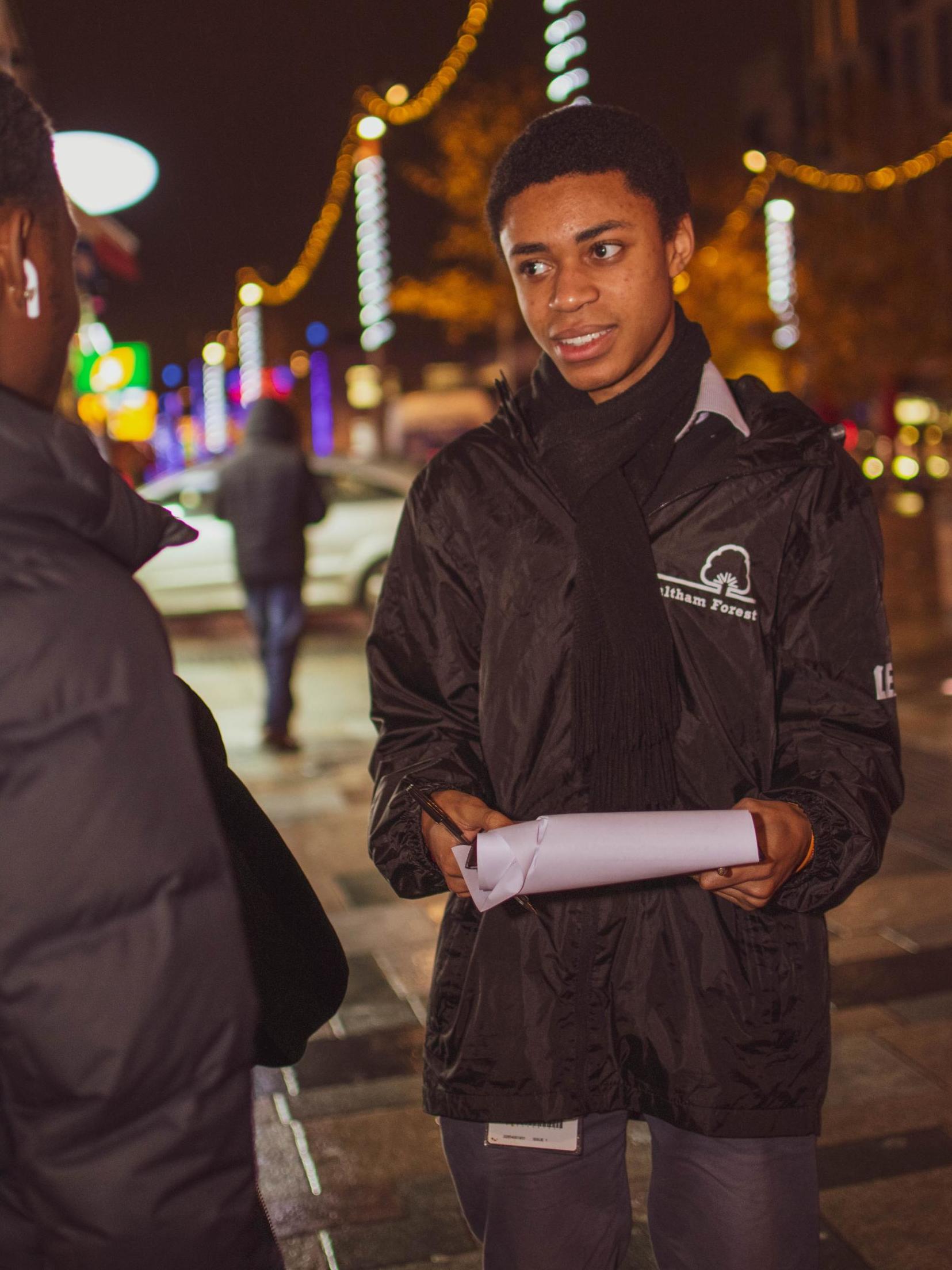

The Independent meets James as he is preparing to go out on a four-person patrol in the borough as part of its new “Streetbase” initiative, funded by the mayor of London. Under the project, people aged 16 to 25 patrol areas of the borough in small groups, engaging with others who may be vulnerable or at risk of getting involved in crime.

The patrol members talk to youngsters and direct them to activities and services to suit their interests and needs. They also run workshops on issues such as stop and search and dealing with anxiety and depression. “I don’t think these kids have many people asking after them or asking them what their interests are,” explains James. “I feel like they just want to be heard and taken care of in a way.”

Some of the kids taking part in the patrols have been caught up in the youth offending service previously, are care leavers, or have been directly affected by street crime. But others have had more ordinary upbringings. All are part of Waltham Forest’s Young Advisors, a group of young people who act as consultants to the council on youth issues.

Tonight, James is joined by Jhanzab, 24, a former young offender turned writer, and Shaidon, 19, who lost a close friend to knife crime in Lambeth, south London, last summer. The patrol will be led by project coordinator Katy Thompson, 22. She explains that while members are not put in harm’s way, they have sometimes acted as a useful bridge between young people and the police, taking the heat out of situations.

“On two occasions we have kind of avoided the whole ‘let me arrest you’ situation and explained things in a respectable manner to both parties,” she says. But she admits: “We’re only six months in and we’ve got funding for three years so I’m sure we’ll come across more intense situations but we’re prepared.”

Streetbase members are trained, paid the London living wage, and provide a unique resource to enable authorities to engage with young people who are often deeply suspicious of the police. In Southwark, south London, where the scheme first originated in 2009, Streetbase patrols have had 30,000 interactions with young people over the past decade. Managers paint a positive, if not particularly quantifiable, picture of their impact.

Last year, Waltham Forest became only the second authority to run Streetbase but Southwark is due to help launch a similar scheme in neighbouring Lambeth this year. As concerns over youth violence rise, and councils look desperately for solutions, Southwark is also in talks with several others about what the scheme offers

Despite the obvious positivity currently around Streetbase, there is more than a whiff of controversy around the concept of “citizen patrols”. Concerns are expressed that they can amount to “policing on the cheap” and that the people involved could be put in danger. In some forms they can even provoke vigilantism.

However, knife crime hit record levels last year and police numbers fell 15 per cent between 2010 and 2018. The number of police community support officers – themselves controversial when they were introduced – fell by nearly 40 per cent during the same period. So it is perhaps no surprise that ordinary people and authorities want to fill in the perceived gaps left by an under-resourced police force.

It is no surprise that ordinary people and authorities want to fill in the perceived gaps left by an under-resourced police force

Different groups with a wide variety of aims and administrative arrangements abound, from informal foot patrols to private policing companies. One high-profile example is the UK branch of New York’s Guardian Angels: written off in the early 2010s as numbers shrunk to just a handful, it now appears at least to be enjoying a resurgence. A spokesperson for the group told The Independent that it has had “very healthy numbers for the past three years” due to recruitment drives and events.

Its Facebook page pictures its red-bereted agents pacing the streets of south London. In 2018, it was reported that two crime-fighting patrol groups in Essex – Night Angel Patrol Group Pitsea and Wick Patrol Group – had become branches of the Guardian Angels, donning the uniform and appearing on morning television.

Other well-known patrols include the church-backed Street Angels, whose work includes supporting people in the streets after they come out of pubs and clubs. Launched in 2005 in Halifax, West Yorkshire, the organisation behind it now says it supports around 150 similar projects across the UK and abroad. Police forces are increasingly embracing the concept of “Street Watch”, which encourages ordinary citizens to don tabards and patrol their local areas for two hours a month.

In the West Midlands, police say they have now set up 170 Street Watch schemes involving around 1,400 people over the past three years. Dr Sean Butcher, from the University of Leeds, who recently carried out PhD research into citizen patrols, said he had been surprised by the “sheer variety of groups” doing everything from offering welfare to clubbers to local residents dealing directly with crime prevention.

The apparent resurgence in these groups comes alongside growth in private security businesses such as My Local Bobby and councils employing policing firms such as Parkguard to fill the gaps in local policing. Despite this proliferation of patrols, the question remains: are they safe and are they effective?

Butcher says that concerns over vigilantism are part of a media narrative that is largely unjustified. Nonetheless, he adds: “You may find one-off examples in the past where communities have done things in the heat of the moment and people have banded together and done things inappropriately,” he says.

He points to the example of the Balsall Heath Citizens’ Patrol in Birmingham in the 1990s. Citizens mobilised to tackle street prostitution but their activities quickly became more “antagonistic and aggressive” he writes in his PhD. “Contact between sex workers and the local outreach project declined as women were harassed while trying to reach the drop-in centre,” he writes.

Accountability, he says, can be a problem. “These groups aren’t particularly accountable,” he says. “If you’ve got an issue with the Street Angels or Street Pastors, who do you go to? You can call the local coordinator, but normally there’s no recourse. People don’t know what their rights are.

“There’s always a possibility that something could go wrong and if it does it’s a problem,” he says.

Ruth Halkon, a researcher at the Police Foundation think tank and a former police officer, says the rise in citizen involvement in policing is understandable but it does not always provide benefits. She says: “I think there is a sense especially with more minor crime that police aren’t really dealing with it, that they’ve got other priorities and the public tend to take matters into their own hands.”

But, depending on the set-up, she agrees these initiatives can go wrong. She underlines the example of online “paedophile hunters” arranging sting operations to entrap paedophiles: there’s a real risk, she says, that they can commit crimes themselves – including assault – if they have to restrain the person. She also points to the obvious dangers of misidentifying someone or compromising an active investigation.

“There’s a balance between people providing a deterrent by being there and taking the law into their own hands…there’s a line that’s not very clear. Often situations which might seem quite low risk might turn into something high risk and if you don’t have the training and resources and backup to deal with that then that could be problematic.

“That’s why the police support is important and there’s back-up there when they need it and they’re not making things worse.”

The biggest issue though is finding evidence of the impact of citizen patrols. Can they prevent crime and disorder? “It’s the million dollar question,” says Butcher. “My sense is that they probably do [prevent crime] just by being out and being a visible presence that members of the public can’t sometimes distinguish from the police; I think it probably encourages people to behave.

“I think they potentially put off low-level acts of criminality. For example, I’ve walked down dark alleyways with the Street Angels and seen people doing things, possibly exchanging drugs, and they would bolt because they’d seen the group.

“But knowing that for certain and judging the extent of that is really difficult.”

Paul Blakey, founder of Street Angels, says violent crime and anti-social behaviour dropped 40 per cent in Halifax when the scheme was first launched in 2005, but adds that it’s now harder to quantify impact because there are far fewer resources to do so.

Anna Kotova, a lecturer in criminology at Birmingham University, says crime-fighting citizen patrols such as Street Watch or private firms such as My Local Bobby can be ineffective in preventing crime because they operate in areas that “need them the least”.

This, she says, contributes to social inequalities and takes the pressure off the government to improve properly funded public policing in tough areas. She adds: “The people who are more likely to be fearful of crime are usually the ones who are less likely to be victims. If you look at the British Crime Survey the people who exhibit the most anxiety tend to be wealthy, white, old ladies. The people who are most likely to be victims of crime are young black men.”

People who are more fearful of crime are usually the ones who are less likely to be victims. The people who exhibit the most anxiety tend to be wealthy, white, old ladies

Experts agree that the best kind of patrols involve citizens with backing from authorities such as the police or council. “Patrols can be useful but they’ve got to be managed,” says Butcher – something that is increasingly difficult with limited resources. For frontline officers, they want to see resources invested properly and partnerships developed.

“That takes time and it’s not a cheap fix. There is this sense that they need to be monitored so they don’t do things they shouldn’t, and that requires investment as far as the police is concerned.”

Halkon agrees that engagement with the police is key: “Youth patrols and Street Watch are a good idea because there’s buy-in from both sides.”

She also points to the Shomrim patrols of the Jewish community in London which have a close relationship with the police and are often first on the scene of an incident.

Some other groups fail to gain police endorsement because they’re “undertaking challenging and dangerous work that should be left to police officers,” she says. “When agreements are in place and each side knows what their role is and the public aren’t trying to replace the police [it goes well].

“Tensions come from individuals who aren’t properly trained or equipped and they’re putting themselves at risk.”

But if the impact of most patrols is not particularly measurable, why do people bother taking part? Faith, in the case of organisations such as Street Angels, clearly plays a role, says Butcher. Others might take part out of fear that the police have forgotten their area, or simply to help others. Some are driven by a sense that they are uniquely well-placed to make a difference.

Streetbase member Shaidon says: “The way I see it, I wouldn’t want my little brother to be led astray or see the things that I’ve seen, so I like spreading that knowledge. In some of the individuals that we come across, I feel like I’m talking to my younger self.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments