Can China succeed in Afghanistan where other empires have failed?

Beijing intends to take advantage of Washington’s ‘irresponsible withdrawal’ and befriend the Taliban and the Kabul government to exploit the country’s vast mineral wealth. Brian McGleenon reports

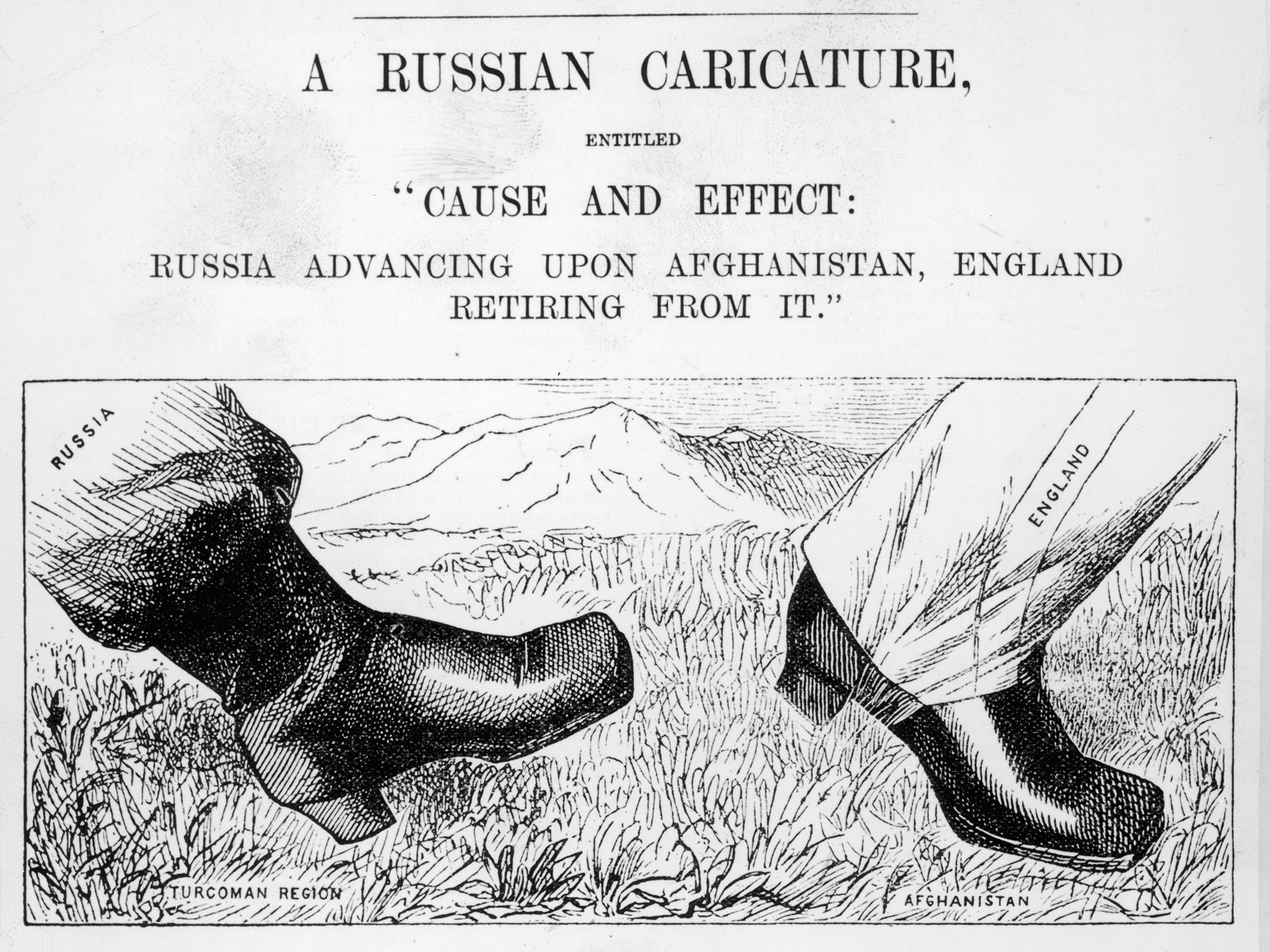

In July 1840, intelligence officer Arthur Conolly urged Major-General Henry Rawlinson to “play the noble part” and advance British values into Afghanistan, saying “you have a great game, a noble game, before you”. This game quickly evolved into decades of political rivalry with the Russian empire, and saw the slaughter of tens of thousands in three costly Anglo-Afghan wars that failed to subjugate this mountainous land known as “the graveyard of empires”.

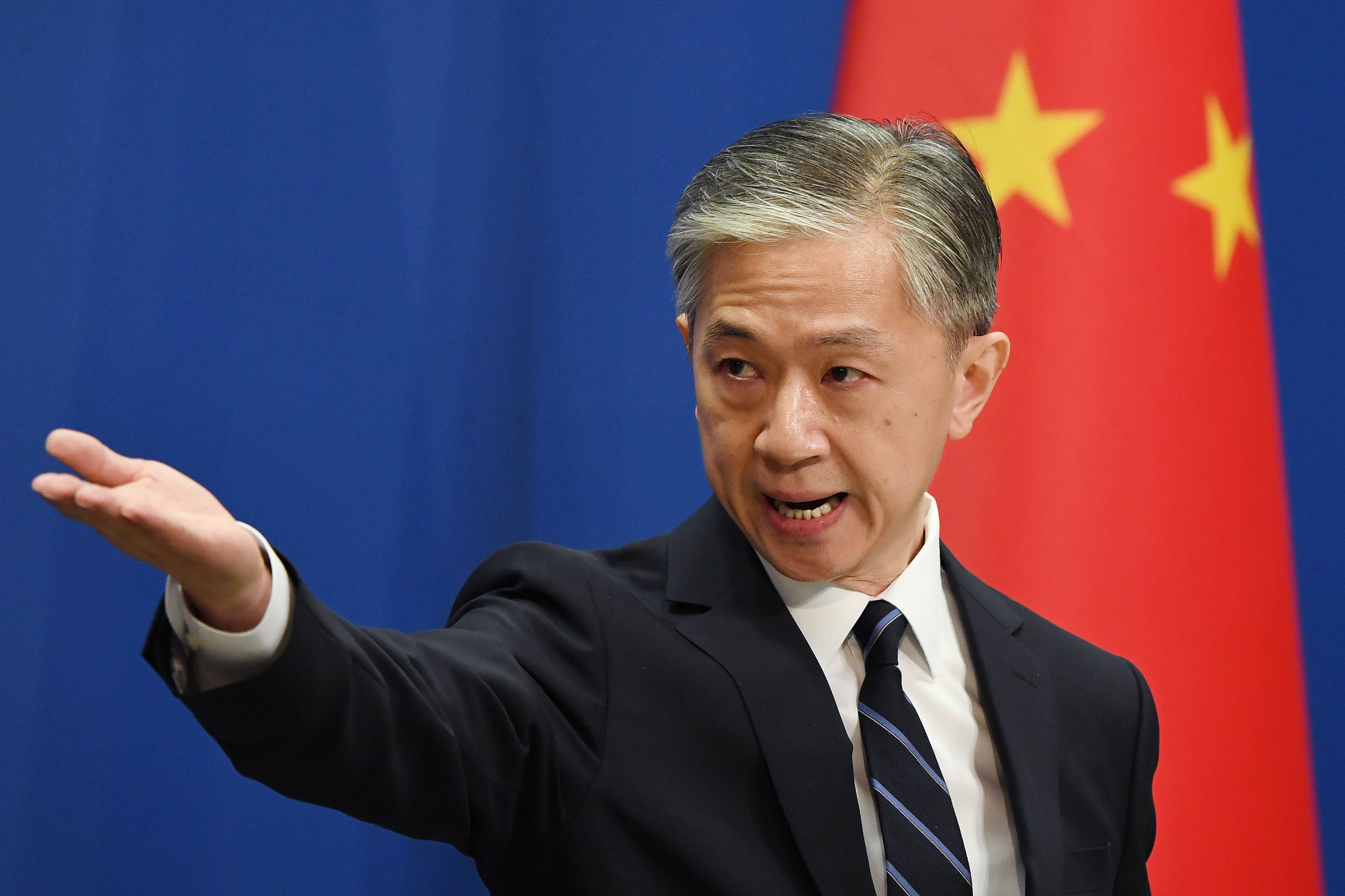

Now, Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson, Wang Wenbin, has responded to the planned withdrawal of US troops by saying his nation should play its noble part in history and advance “peace, reconciliation and the reconstruction of Afghanistan”. As Mark Twain said: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

Afghanistan has seen conquerors come and go since the time of Alexander in 330 BC. The United States is the latest power to vacate the region unfulfilled, with its forces scheduled to be fully removed by 31 August 2021. This will conclude the nation’s longest military engagement and one that saw 2,312 US fatalities and an estimated 35,000 to 40,000 civilian casualties. But influence over Afghanistan, long referred to as central Asia’s geopolitical pivot, is tilting eastward and into the extending grasp of an ascendant China.

In a famous 1904 lecture, British geographer Sir Halford John Mackinder argued that long-term global hegemony was the reward of the world power that controls the geographic centre of Eurasia, roughly corresponding to the borders of Afghanistan. The landlocked nation is the hub of which Iran, Russia, India, and China are the rotating spokes. Now a cacophony of jingoistic rhetoric is spilling out of China, from official sources and a multitude of netizens, that urge the Middle Kingdom to exploit Washington’s “irresponsible withdrawal” and show the world that it can succeed in Afghanistan where the other empires failed.

The power vacuum will be a threat and a temptation for Beijing. According to the CCP, the threat would stem from unchecked drug traffickers and East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) separatists, escaping from the highly securitised province of Xinjiang in western China. However, a potent temptation has unravelled itself, the opportunity to extract Afghanistan’s vast mineral wealth, reportedly worth more than $3 trillion.

Anders Corr of the Journal of Political Risk says: “China is primarily concerned about its investment in potentially trillions of dollars of mineral resources in Afghanistan.” The nation has abundant mineral deposits, ranging from copper, iron and sulphur to bauxite, lithium and rare-earth elements essential for the tech industry. A view also held by Professor Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at the SOAS University of London, who says Beijing’s early involvement in Afghanistan will focus on exploiting “extractive industries and infrastructural building”.

However, he added this extraction escapade will see China “operate in an insecure environment and it will need protection” and once “directly involved the risk of unintended escalation will increase”. He described how Chinese personnel and investments will be affected by the general insecurity and chaos in Afghanistan and that Beijing’s “efforts to protect its citizens and investments will carry a high risk of escalation”. Newsweek columnist and author Gordon G Chang claims that for China to exploit Afghanistan’s vast and untapped mineral resources, "it’s going to be pretty expensive for them to get it out, the cost is going to be much higher than they presently contemplate”.

Chinese geopolitical observers are confident that Beijing will succeed in delivering their aims in Afghanistan because they will apply ‘the Chinese way’ of exerting control

For China to succeed in their attempts to extract these vast resources they’ll need the assistance of the Taliban, which is rapidly re-establishing itself across the country since its Islamic theocracy was toppled by the US in 2001. According to Nick Carter, chief of the UK’s defence staff, and US General Scott Miller, it is “plausible” that Afghanistan could now collapse into an all-out civil war.

Already US-backed Kabul-government forces are fleeing reprisals and crossing the border to Turkmenistan and Iran. Meanwhile, according to This Week in Asia, the Taliban is encouraging China’s intervention in the looming power vacuum, with spokesman Suhail Shaheen saying that “if they have investments, of course, we will ensure their safety, their safety is very important for us”.

Beijing could thus begin a problematic partnership with a fundamentalist organisation that, according to the UN, caused 76 per cent of civilian casualties in Afghanistan in 2010, 80 per cent in 2011, and 80 per cent in 2012. However, Corr says that this working relationship has already been demonstrated when “China likely provided the Taliban with something of value in order to get Taliban approval for its mining at Mes Aynak”. Two Chinese companies acquired a concession to mine at Mes Aynak in 2008, which is said to hold the second-largest copper ore deposits in the world.

But can the Taliban ignore the re-education camp conditions among their fellow Muslims in neighbouring Xinjiang? It is estimated that China’s securitisation of Xinjiang has seen the incarceration of approximately 1.5 million Uyghurs in an attempt to force Muslims to conform to the official doctrines of the CCP. The Taliban may well forecast that the iron-grid securitisation implemented in Xinjiang could, in due course, be visited upon their own heads. However, Professor Tsang tells me that if the Taliban was taking the Uyghur cause seriously “it would not work with the Chinese at all”. He added: “The fact they are prepared to talk to the Chinese state implies they take a utilitarian rather than principled approach over this.”

Chinese geopolitical observers are confident that Beijing will succeed in delivering their aims in Afghanistan because they will apply “the Chinese way” of exerting control, and if this distinct method triumphs Beijing could score a major foreign policy coup de grâce against the US. The politburo in Beijing has mythologised China’s “peaceful rise” to world super-power status, made possible by its “win–win” approach to international diplomacy. Writing in China’s state-run tabloid the Global Times Professor Zhang Jiadong states that China’s inroads into Afghanistan would follow its “non-interference principles of diplomacy”. He added that Beijing will not “fall into the Afghan trap that other powers have because China has the ability to get involved in the nation’s affairs without becoming entangled in them".

This is a view supported by the chairman of Dezan Shira and Associates, Chris Devonshire-Ellis, who describes China as being more sympathetic to the diplomatic values of Afghans. Devonshire-Ellis describes the Chinese as understanding ingrained traditional hierarchies rather than the liberal principles of western representative democracies. He says the Chinese are “more respectful of the views of Afghan elders whose wisdom gained at great life experience is greater than that of an 18-year-old who would otherwise under ‘western democratic values’ have an equal right to vote”.

This is an attitude held by the politburo in Beijing, which maintains a low view of universal suffrage, leading to the probable dismantlement of the democratic systems established at such a cost by the US if Beijing succeeds. Devonshire-Ellis added that “the Chinese also respect their elders and operate a partially democratic regime within their party structure, comprising the ideals of discussion, research and trial and error”. According to Corr, China’s intervention in Afghanistan has a higher chance of achieving its goals than the ambitious task attempted by the US and Nato to install “democratic governance” in the nation.

In contrast, the less complex goal that China desires with its “non-interference method” is prolonged resource extraction. Corr added that “given China’s goals, it has no need to fight the Taliban and other illiberal forces in Afghanistan. It just needs to bribe the Taliban and Kabul government to extract the resources peacefully”. Devonshire-Ellis forecasts the most likely scenario to play out in Afghanistan is that Beijing will do a deal with the Taliban. It “will tell them to keep to their side of the border and that what they do in Afghanistan is their own affair, provided it does not upset the Chinese, who will be more seductive in their approach, less gung ho, and try to persuade the Taliban that peace via trade is better than armed conflict”.

Currently, the country is officially called the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and has a precarious democratically elected government. However, China looks set to facilitate the installation of a Taliban-led Islamic theocracy, even though this contradicts Beijing’s own rhetoric of eradicating “backward” Islamic culture in its troubled western province of Xinjiang. The politburo has spent billions on its campaign against the three evils of “terrorism, separatism and religious extremism”. But, in its relations with the Taliban, China is taking a more pragmatic approach, propagating a symbiotic relationship where the Taliban would receive the economic and political support needed to set up their new emirate from China, via their ally Pakistan.

The fundamentalist group could earn revenue from transit fees from Chinese developed pipelines passing through the country from the gas fields in Turkmenistan. Central Asian produce could reach Pakistani ports if Afghanistan was secured with Chinese help. Benefiting from Beijing’s validation, the Taliban would also be given credibility on the world stage and could even become members of the Chinese political, economic, and security alliance, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. In this arrangement, China would get the vast mineral and petroleum reserves and the guaranteed safety to siphon them out of the country. Beijing would also benefit from a Taliban promise to not support and give sanctuary to the ETIM, which threatens Chinese interests in Xinjiang.

It is a gamble of high stakes where Beijing hopes to tread a fine path of being a friend to both the government in Kabul and the Taliban

Others see this alliance as only working on paper and that Beijing would need to remember that the US also played this pragmatic move by assisting the Taliban against the Soviet Union in the 1980s, only to become their enemy two decades later. Director of the Uyghur PEN Centre, Aziz Isa Elkun, says the Taliban is not the only ethnic group that the Chinese will have to contend with. He said that in Afghanistan “the Tajik and ethnic Uzbek, and other Turkic people ethnically, linguistically, and culturally share the same heritage with the Uyghurs and there is already extreme sympathy towards the Uyghurs, and they have shown their anti-China stance already”.

He added that this would become problematic if the Taliban was seen to be collaborating with the Chinese and he foresees Afghanistan beset by “another decade of civil war that may spread to Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan”. He added: “Taking account of the political reality, landscape, and the various ethnic people, plus the existing Islamic jihadists, there is no chance that China can succeed."

US-China expert Gordon Chang echoed the view expressed by Elkun, that Afghanistan’s complexity of ethnic factions, who each have “very different interests”, has been dangerously underestimated by Beijing. Speaking to Fox News last week, Chang suggested that "India could play these groups against China in Afghanistan, bedevil the Chinese, bog them down”.

The hawkish China expert then gave a knowing smile and added that he “would love to see China get mired in Afghanistan, this is going to be fun to watch”. The prospect that China’s competitors would seek to sabotage the nation’s attempts to control Afghanistan is also expressed by Devonshire-Ellis, who suggested that the US will “leave ‘agents’ behind who may well try to create divisions and problems” for China in Afghanistan. This is reminiscent of the famous novel Dune by science fiction author Frank Herbert, where the Atreides accept an opportunity to become the new controllers of the spice-rich planet Arrakis after its former masters, the Harkonnens, suddenly evacuate. However, in the novel, the Harkonnens intentionally pulled out to set a trap that the Atreides walk into.

The Chinese are aware of the double-edged nature of the opportunity that has presented itself in Afghanistan. It is a gamble of high stakes where Beijing hopes to tread a fine path of being a friend to both the government in Kabul and the Taliban. The Global Times attempts to alleviate concerns with self-delusional statements that the Taliban has “quietly transformed themselves to improve their international image, easing the concerns of and befriending neighbouring countries”.

But how long before the Taliban reverts and make Afghanistan a refuge for al-Qaeda, Isis, and Xinjiang separatists, all enemies of Beijing. Renewed conflict in Afghanistan is a situation that would benefit the US if it ties down Chinese military resources. The Taliban has shown it is a master of protracted hostilities and has a saying that when fighting superpowers, “they have the watches, but we have the time”.

Professor Tsang warns that for China “this may be one ambition too far, but it will be some years before the reckoning will come”. He then added that “any partnership between China and the Taliban will be one of convenience and will not last”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments