Communism 2.0: China, capitalism and the growth of new world socialism

The seismic shift from Soviet-style communism 1.0, based on heavy industry, to China’s AI-supported communism 2.0 can be observed to different degrees across seven communist states, writes Tomasz Kamusella

After the 1989 fall of communism in the Soviet bloc, five self-declared communist states remain today: China, Cuba, Laos, North Korea and Vietnam. Belarus and Venezuela can also be added to the mix as they fulfil the criteria of a communist state – even though they do not officially invoke the ideology. So, at present, the number stands at seven. The question is, now that capitalism is the engine of China’s economy, what is communism today? And if the number of communist states is poised to grow in the near future, as some predict, what does this prospect mean for democracy?

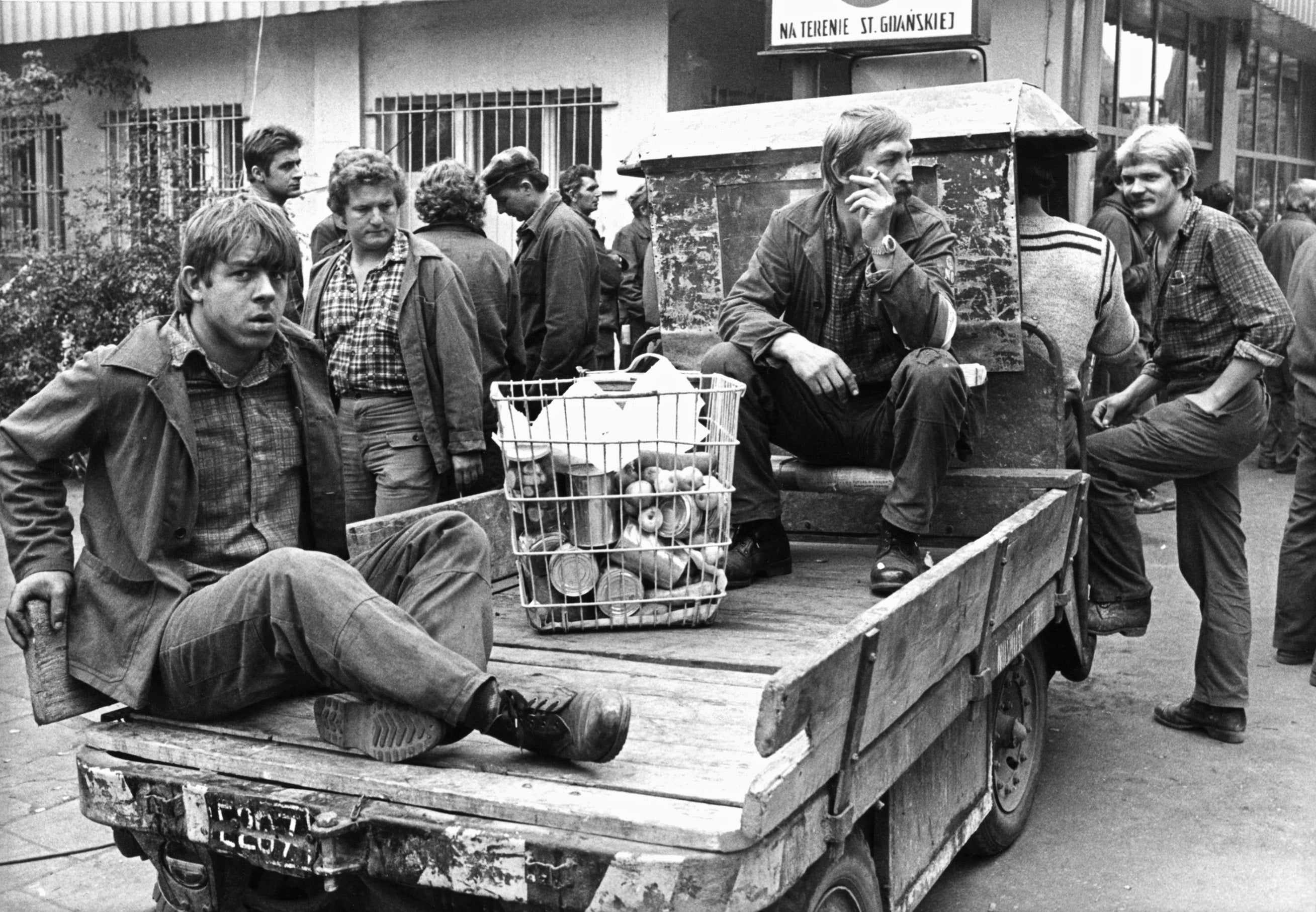

My interest in communism goes beyond my work as a historian – it’s personal. I was born and raised in communist Poland in the 1970s and 1980s. It was a grey country where people seemed to have lost all hope. All essentials, including shoes and coffee, were rationed. But rationing cards did not mean you would get what you wanted, or even needed. Queueing for hours – sometimes even days – to buy anything that had just been delivered to a shop was a regular occurrence.

I have no doubt that my upbringing shaped my life and inspired my career. My research has examined modern central and eastern Europe, nationalism, and the politics of language – particularly in the region’s totalitarian and authoritarian regimes during the past two centuries.

During my youth in the 1980s, bartering became more common, while scarce goods could only be bought with US dollars. You could exchange a summer dress two sizes too large for a T-bone steak (kotlet), or a record player that you did not need for a large can of baby formula. Only vinegar seemed to be in constant supply on the near-empty shop shelves – perhaps accounting for the sour faces and almost permanent lack of smiles. Western scholars came up with an apt term to describe this existence. They called it the “economy of scarcity” – the impact of central planning on production and the population.

And it wasn’t just a lack of food. Freedom was scarce, too. Poland, like all Soviet bloc countries, was kept under a “double lock” – meaning it was even difficult to travel to another socialist country, be it neighbouring Czechoslovakia or East Germany. You needed to apply for a particular kind of passport to travel to the “people’s democracies” – that is, Soviet bloc countries – in Europe. And after coming back home from your travels, this precious document had to be returned to a local militia headquarters – the police then were known by this militarised sobriquet.

If you wanted to visit a European capitalist country, like West Germany, you needed another kind of passport. But only a single member of any family would be allowed to go to the “rotten capitalist west”, as it was often referred to. So the rest of your family remained as the state’s hostages to ensure you wouldn’t dare to defect. I never once saw the passport that permitted travel to all the countries of the world, which allowed the lucky few to travel to the US or Australia.

To me, and many others, my home country felt like one big prison. Stringent censorship of publications, films and television aimed to convince us that life in Poland and the Soviet bloc was much better than in New York or Paris. But few believed the propaganda. People clandestinely listened to Radio Free Europe and Voice of America – despite the state attempting to jam them. And during the 1980s, it became easier to buy banned books in the form of samizdat – uncensored, underground publications.

Among the youth, the dream was to escape this prison and enjoy a normal life in a normal country; in a place with no rationing cards and well-stocked supermarkets, where working a single job you would be able to afford a decent standard of living, an apartment, and summer holidays in the Canaries. The slang Polish name for this Spanish archipelago, “Kanary”, became colloquial shorthand for the unattainable.

Pie in the sky, our parents warned us. Their advice was to be quiet, to do what we were told by teachers or overseers – and to never say what we thought. After all, refusing to toe the Communist Party’s line, or not praising Poland’s socialism – let alone opposing the system – might cost you a coveted place at a university, or the loss of an apartment, or even land you in prison. In the 1950s, at the height of Stalinism, people were even executed for such ideological misdemeanours.

But, unexpectedly, the cold war between the western democracies and the communist Soviet bloc came to an end in 1989, followed, two years later, by the collapse of the Soviet Union itself. This communist superpower simply and peacefully – at least in Europe– vanished into thin air, causing communism as a political and economic system to disappear from much of the world.

We were free. The last general secretary of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, was the good fairy who made our heartfelt dream come true. The Soviet leader decided that starving his own people in order to keep up with the west in the arms race was no way forward. The subsequent systemic transition, within the span of a decade and a half, enabled former Soviet bloc states, from Poland and Hungary to Romania and Bulgaria, to accede to Nato and the European Union.

Beijing has been proudly communist since 1949 and is now taking on the US, which still leads – though falteringly – the globe’s shrinking camp of democracies

With my newfound freedom, I continued my education in South Africa and the Czech Republic. I researched in Italy, the US and Japan, before finding university positions in Ireland and Scotland. But in the case of the 15 countries that emerged from the defunct Soviet Union, only the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania became truly western and democratic. Most, Russia included, became autocracies – even if they stuck to the pretence of parliamentary elections.

Georgia, Moldova and especially Ukraine are tantalisingly close to becoming genuine democracies with the prospect of EU and Nato membership. Yet, Turkmenistan is almost as oppressive as North Korea, while Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan are seen as textbook examples of repressive and kleptocratic dictatorships.

But at present, not a single post-communist or post-Soviet state declares itself to be communist.

China leads the autocracies

With the economic and political demise of Soviet-style communism, most of the communist regimes supported by the Soviet Union across the world, like Ethiopia, Afghanistan and South Yemen, also collapsed. Communist Cuba is a lone exception to this trend. The Caribbean island has been a permanent thorn in the side of the US since 1961.

Present-day communism, then, is led by China – the world’s second-largest economy. Beijing has been proudly communist since 1949 and is now taking on the US, which still leads – though falteringly – the globe’s shrinking camp of democracies. Since 2010, an increasing number of states have parted with democracy.

Over the past decade, democracy has been quickly reversed in post-genocide Rwanda. The same has also happened in Ethiopia as a result of the civil war in Tigray (2020-present day), while the Arab spring’s democratic gains have been squashed across the Middle East. As in Putin’s Russia, electoral autocracies were installed in Bulgaria (2009), Hungary (2010), Serbia (2014), Turkey (2015), Poland (2016) and Slovenia (2020).

China’s population of 1.4 billion means that a fifth of all humankind lives under its communist regime. The other three self-declared communist states – Laos, North Korea and Vietnam – all border China. A new communist – and Sinic (Chinese influenced) – bloc, indeed.

So, after the two decades of decline in the wake of the 1989 collapse of the Soviet bloc, is the turbocharged Chinese-style communism 2.0 – which embraces capitalism – going to take over?

The rise and fall of democracy

The looser post-Cold War definition of communism marries capitalism with socialism, as understood in the former Soviet Union. The overarching principle of socialism – seen as communism in the west – says: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his contribution.” In practice, this unorthodox mix of Soviet-style socialism and capitalism means an authoritarian, or even totalitarian, regime under a single party’s full – and, these days, AI-enhanced – control. This control extends over the now capitalist-style economy, too. Through this mono-party, the invariably male leader single-handedly rules.

Often a cult of personality is developed around him, and the deal is sweetened with a modicum of a welfare state. In most cases these states advertise themselves as being communist. Others, like Belarus and Venezuela, may not actually call it communism, and a different name may be given to this ideology – for example, Bolivarianism in Venezuela, national unity in Belarus, or Juche in North Korea.

The mono-party political system makes the Communist Party into the state and its leader into the de facto dictator. Unchecked collectivism, or the ruling dictator’s self-serving and populist rhetoric of prioritising masses – referred to as “the nation” or “the people” – over individuals, justifies his rule and the system. In places like Belarus and China, this has led to dissenters being repressed, and concentration camps being built to remove them from “healthy society”.

Communist-capitalism is not an oxymoron any more, as long as the ruling Communist Party keeps entrepreneurs subservient to its ideology and governance

Like the pre-1989 communist states, all these countries’ ruling regimes are anti-western in their official rhetoric, and often in their actions too. This anti-western aggression was another important defining feature of the communist states of the 20th century.

But will this number rise or fall in the 21st century? During the two decades following the fall of communism in Europe, democracy as the doctrine of human and political rights steadily spread across the world. Dictators felt pressured to keep up at least the appearance of working electoral democracy in their countries. Amnesty International and Freedom House successfully shamed autocrats into mending their notorious ways and freeing political prisoners.

But after 2010, this trend was incrementally reversed. Symbolically, in this year the Chinese writer and pro-democracy dissident Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Beijing felt offended by the west and took steps to suppress Liu, his family and friends. The authorities denied Liu cancer treatment, and he died prematurely seven years later.

Liu’s ashes were scattered in the sea to prevent the establishment of a grave for a person many saw as a democratic hero and martyr. That would have been a focal point for China’s democrats, who might have gone on pilgrimages to pay their respects to Liu’s unwavering loyalty to liberty and democracy.

Then, in 2020, the pandemic created an ideal opportunity for Beijing to dismantle democracy in Hong Kong, and a place that was once a beacon of political and economic freedom fell. Autocrats of all stripes took note.

‘To get rich is glorious’

But isn’t the whole idea of capitalism and profit anathema to the central tenets of communism? And if so, how did these two opposites attract? In the wake of the then Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 reforms, a great discovery of applied politics was made in China: that you could have capitalism without democracy. Spotting a gap in the market of ideas, Deng decreed that “to get rich is glorious”, meaning that capitalism was ideologically neutral and could serve the needs of a communist regime.

The current marriage of capitalism and communism is a lesson for democrats not to trust in their wishful thinking. Instead, the often-touted hypothesis about capitalism’s democratising effects must be put to the test. It is clear that capitalism does not make authoritarian or totalitarian Belarus, China, Laos or Vietnam any less authoritarian or more pro-democratic or pro-western.

Cuba, North Korea and Venezuela ditched capitalism once before when they became communist, in 1948, 1949 and 1999 respectively, and they are reluctant to re-embrace it. But China’s enthusiasm for undemocratic capitalism since 2004 – known as the Beijing consensus in the west – may compel them to follow suit soon.

China’s economic success, if it lasts for several generations, may lead to the fortification of nascent communism 2.0, with capitalism as an integral part of this ideology. Communist-capitalism is not an oxymoron any more, as long as the ruling communist party keeps entrepreneurs subservient to its ideology and governance.

So what are the specific characteristics of the new communist 2.0 state? Perhaps, the self-declaration of being a communist state is the most obvious – and that this features in the constitution, even if some states give it a different name.

Civic and human rights are seriously limited and often denounced as a “western ploy”. For instance, no individual right to vote exists in China, while the state owns citizens’ bodies to do with them as it pleases. A similar level of abuse is observed in North Korea and Vietnam. And growing repression has also been observed in Belarus and Cuba.

Recently, the west woke up to the dangers that its liberal and democratic values may face, and the fact that capitalism alone cannot guarantee freedom and human rights. The fear that the age of communist China’s imperialism has already arrived motivated Australia, the UK and the US, for example, to form a new military pact. Imperfectly – and probably to Beijing’s delight – the Aukus agreement excludes the EU.

Technological totalitarianism

In China, the traditional features of totalitarianism have become irretrievably combined with the system’s appetite for hi-tech conditioning and surveillance. For example, the total control of Xinjiang’s Muslims is made possible through the region’s mass database of the population’s DNA and irises.

To curry favour with Beijing, Europe’s aspiring autocracies are busy dismantling democracy and putting curbs on political rights and freedoms at home

Technology and AI are communism 2.0’s largely bloodless methods for extending total control over the population, making sure that every individual toes the party’s line. This compliance is also enabled by the emerging military surveillance industrial complex, which is going to be at the core of successful communist-capitalism.

More control means more job openings in this complex, directly translating into economic growth, which in turn will go back into financing that control – totalitarianism’s perfect feedback loop, with no way out. And so repression becomes recognised as the engine of the economy; a guarantee of prosperity for most – though not all.

The seismic shift from Soviet-style communism 1.0, based on heavy industry, to China’s AI-supported communism 2.0 can be observed to different degrees across those seven communist states. North Korea remains an outlier and a squarely communism 1.0 state. To this day, Pyongyang refuses to follow the communism 2.0 path, despite Beijing’s quiet nudges in that direction – although there are signs that this could be changing.

Cuba and Venezuela, meanwhile, are also closer to communism 1.0, still making non-pragmatic choices informed by idealism and ideology. At the other end of the spectrum, Belarus, Laos and Vietnam are using whatever works economically – as long as the ruling party controls production and profits. They are China’s conscientious pupils, bent on implementing communism 2.0.

Democratic alternatives

Unless the world’s democracies come up with attractive and effective solutions to socioeconomic ills such as unemployment, falling living standards and income, and inaccessible medical care, then I am afraid that communism 2.0 is going to win hands down. In this scenario, the number of communist states is bound to grow and individual and political freedoms will diminish.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is exactly the type of ambitious project that the world’s democracies acutely lack at this moment in time. The plan is to link and build a coordinated network of railway, road and maritime corridors to span all of Africa, Asia and Europe for the seamless export of products from China and the easy import of raw materials to this communist powerhouse.

Not only does the BRI already facilitate China’s exploitation of Eurasia and Africa, but it also functions as the main conveyor belt for spreading communism 2.0 globally.

Adoptions of the Chinese model’s signature mix of welfare-state policies with growing authoritarian tendencies and a single party’s aspiration to seize all power have been observed in present-day Europe since 2015, be it in Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland or Serbia. Unsurprisingly, these countries’ pro-authoritarian leaders are enamoured with Chinese economic and political success. They hope to establish privileged links and collaboration with the communist superpower, and they may not be the last western states to fall under its spell.

To curry favour with Beijing, Europe’s aspiring autocracies are busy dismantling democracy and putting curbs on political rights and freedoms at home. Since 2015, Poland has repeatedly been risking tens of billions of Euros in developmental aid from the EU by rejecting the basic principle of EU legal primacy. Facing growing censure in 2017, incredulously, the Polish prime minister said that it did not matter, because in such a case China would offer Poland more money than Brussels.

I fear that, after my childhood in communist Poland, I may have to live out my old age under a communist 2.0 regime of renewed oppression. However colourful and hi-tech its facade may be, the enforcement of the ruling party’s line in this possible future will be swifter and more totalitarian than in the Soviet bloc’s pre-cyberspace past.

Vast databases of citizens’ DNA and irises will make personal identifications impossible to fake, while the ubiquity of online, mobile and CCTV monitoring will liquidate privacy and any possibility of organised dissent.

In the state’s gaze, each person will stand naked with no choice but to do the autocrat’s bidding or be vanished and die, forgotten by all, out of sight in a “black jail” or in an officially non-existent concentration camp.

Even the memory of such an ideological miscreant will be erased from people’s minds, thanks to the rise of the state-controlled “sovereign internet”. As George Orwell predicted in 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future.”

Tomasz Kamusella is a reader in modern history at the University of St Andrews. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments