Is cheap private healthcare killing the NHS?

For those who can afford it, the pandemic has made paying for healthcare a better option than waiting for the NHS. Hannah Fearn asks what this might mean for the future of the service

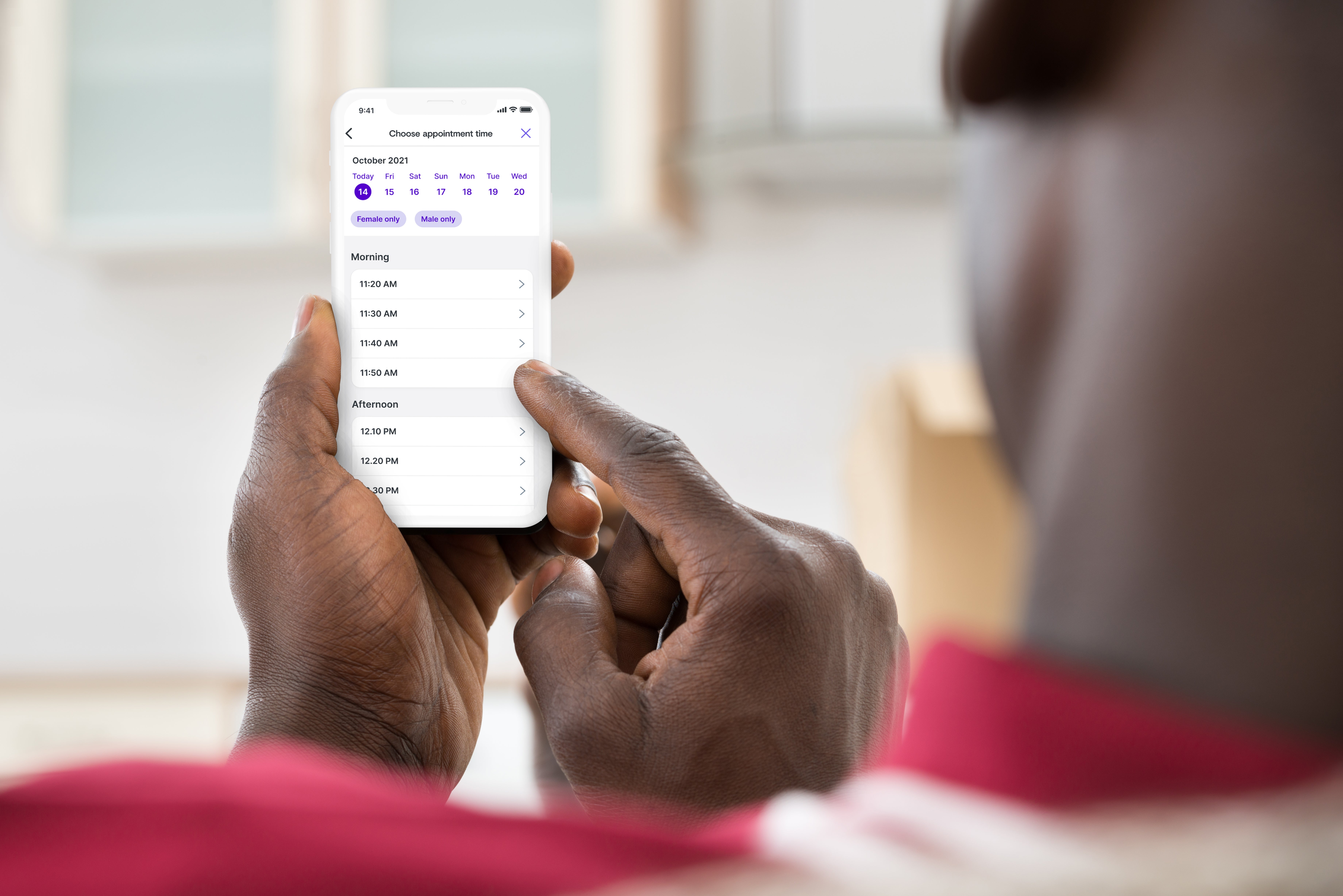

During the early months of the pandemic, John (not his real name) needed to see a GP. He heard from family members that it was difficult to get through to NHS surgeries due to access being limited, morning phone lines jamming up with desperate patients. “I was in a lot of discomfort and felt it was urgent to get some medical advice, and I was uneasy about covid and going to a walk-in centre,” he explains. Instead, John decided to try out private medicine for the first time: he booked an appointment to see a virtual GP using an app for a one-off fee of £50. “It was a brilliant experience,” he says.

John works in a politically sensitive job, so feels unable to talk about his experience openly, but it has changed his opinion about private medicine and the NHS. “I do feel comfortable paying for private healthcare,” he says. “It was really easy. It feels more practical for modern life. I do prefer using these services and I will stick with them. However, I acknowledge that I’m in a fortunate position where I can afford to do this.”

John now says although he would rely on the NHS for a serious or prolonged condition, for minor or easily resolved medical complaints going private instead of trying to get a GP appointment is a “no brainer”. “Perhaps I feel a disconnect with my GP because I haven’t had one locally for a long time,” he reflects. “I am a firm believer in the NHS and worry about creeping privatisation [so] I think that private providers should be an alternative to, not a replacement, the health service.

John is not alone. His shift in attitudes has been shared by many during the difficult months, and now years, of the pandemic. Communications advisor Paul Brannon discovered he had access to the Babylon app, which allows users to make a one-off appointment with an online GP on a pay-per-use basis, through private medical insurance that he already held. “I started using it during the pandemic out of sheer convenience and speed, and I’ve continued using it since as my GP surgery is always so busy it’s hard to get a timely appointment,” he says.

Brannon describes the appeal of digital medicine as a “generational thing”. For those who have moved a lot and perhaps never built a relationship with a traditional family doctor, then seeing a GP you don’t know but who can be accessed very quickly at the click of a button – and a credit card – is an attractive proposition. Is there a moral dimension to this decision too? Brannon thinks so, but perhaps not the ethical question you’re expecting. “In terms of paying, I don’t mind. I think if you can afford it you should free up some NHS capacity,” he says.

It’s not just quick GP appointments that are attracting pandemic-fatigued patients away from NHS care. Older people with savings who may need non-urgent procedures are making the decision to pay for those treatments in ever greater numbers, as the benefits of greater quality of life balance against long and growing NHS waiting lists.

According to a recent IPPR report on the state of health and care, the decline in access to NHS services because of pandemic infection controls, staff shortages due to sick leave and the urgent backlog of outstanding care has led to the perfect conditions to encourage those who have the financial means to “opt out” of the NHS. Although the report reiterated that there is still “near universal” support for a tax-funded health service free at the point of use, the pressures on the system are changing attitudes and behaviours around personal medical consumption.

IPPR and YouGov polling estimates that 16 million adults had trouble accessing the NHS during the pandemic and, of those, 12 per cent went on to use some form of paid-for provision; more than a quarter (26 per cent) had at least considered it. Those figures shoot up the higher the socioeconomic grades you climb. People living in London and those aged 65 were the most likely to have tried private care during the pandemic, but the trend was widespread.

I think the equation that people are making is that the prices for these procedures are not outrageous, they’re within the reach of many middle-class families

The rise in the use of private medicine has also, unsurprisingly, coincided with a change in attitudes to the quality of that service. A vast majority now say that private treatment is either better or equal to NHS care. Only 12 per cent say the NHS outperforms the private sector. This environment risks undermining the NHS, not by political decision through privatisation but by stealth, creating a two-tier medical system with those who can afford to opting out of NHS care for at least some of their medical needs.

As the IPPR report concludes: “The risk is less a sudden privatisation, and more an emergence of something resembling the English education system – where the very best education is so often conditional on ability to pay (either private school fees, or via increased house prices). If this were to become the new normal after the pandemic (as it has in social care and dentistry), it would worsen overall health and widen inequality.”

Chris Thomas, principal research fellow at IPPR, says the motivation for opting out differed among age groups but the trend repeated itself across young and old. Young people were more likely to have less confidence in the NHS, and this may be partly a result of them having less contact with the health service and also being triaged by overstretched services as less of a priority. The fact that GP apps are an easily manageable cost, operating from around £7 a month and up, which Thomas describes as akin to a Netflix subscription. It’s a digestible and familiar type of cost for young people regularly using subscription services.

Report co-author Victoria Poku-Amanfo, a researcher at IPPR, said for young people the failure of NHS mental health services was pushing them towards the private sector. The pandemic years have led to a 74 per cent increase in referrals to mental health services for young people, a part of the NHS already under extreme pressure. Waiting times were also adding to young people’s distress and anxiety, she reported, leading to changing attitudes towards the responsiveness and reliability of the NHS for this group.

For older people the driver is more likely to be something different: the chance to buy back access to better quality of life more quickly. According to health consultant Richard Vize, a former editor of the Health Service Journal, relatively modest prices for what can be life-changing procedures – such as £13,000 for a hip replacement or £2,500 for cataract surgery – mean that older people are increasingly willing to put a personal price on their own independence, as they know “there’s a risk of it being a one-way street”.

“I think the equation that people are making is that the prices for these procedures are not outrageous, they’re within the reach of many middle-class families, and if someone in their fifties, sixties or seventies, they’re making a big trade-off in terms of waiting for an operation and sacrificing quality of life,” Vize says.

Vize confirms that, “both anecdotally and in the data”, there has been a noticeable increase since 2020 in the use of private healthcare. The rise in interest in healthcare insurance is confirmed by a marked increase in traffic to price comparison websites looking at purchasing these products, but there has also been an increase in so-called “out of pocket” spending too, and this is increasing more rapidly.

But what might be a rational personal and financial decision for one individual has ramifications when it’s repeated right across the population. If people are opting out of the NHS, the long-term risk is that the public health service begins to be viewed as a second-rate service for emergencies only, rather than an important part of our daily lives as citizens. “It does begin to undermine the social solidarity aspect of the NHS. The whole point is that it’s free at the point of need and everyone benefits,” Vize says.

More importantly, there are deep ethical issues already creeping into this two-tier system. It’s worth noting that the distribution of long NHS waiting lists is not even across the country, and waits tend to be longer in more deprived areas. Birmingham in particular is struggling with a huge NHS backlog. If you live in one of the most deprived parts of that city, you’re statistically more likely to be chronically sick, more likely to face a long waiting list for even routine treatment, and far less likely to afford to buy your way out of that predicament. “There’s a real health inequality side-effect of these daily decisions,” Vize reflects. “If you go forward a number of years and we are still plagued with very high waiting lists for planned care then it really does start to open up important issues: why should someone with a good income be able to avoid the loss of quality of life from waiting for an operation? That starts to become quite a gross comparison.”

Patients who felt the draw to private digital health services for ease of access can now access these same services on the NHS free of charge

It’s maybe this moral equation that plays such an important role in preserving the political security of the NHS. Like the Ipsos study, a recent poll of public attitudes carried out by Engage Britain also confirmed a deep attachment among Britons to the NHS as a free-to-use universal system: 77 per cent even said the NHS made them proud to be British. An overwhelming majority (85 per cent) also agreed that workers in the health service are overstretched and trying their best.

“It is kind of the national religion in the UK,” says Julian McCrae, director of Engage Britain. “You get a deep sense of gratitude. The two are very strong, with a very widespread basis of support for the system.” So the settlement that we’ve had with the NHS since the 1940s has never been challenged by any political party, and the polling data shows there’s no danger of that happening now as it would be too politically dangerous. But nevertheless, opt-out rates were even higher: one in five admitted they had gone private in 2021 because they couldn’t get the treatment they needed on the NHS.

“The practical implications of not being able to be treated are causing a lot of anxiety. There is no social change in fundamental attitudes to the NHS, but what we do hear is waiting lists and length of time: ‘I love the NHS… but I’ve been waiting this long so I went private’,” McRae says. His researchers also identified multiple cases of families who had taken the private route despite feeling both ethically reluctant to do so, or even admitting a lack of resources to do so. Some had gone as far as to extend a mortgage or take out a loan just to access the treatment they needed during the covid era.

The UK is facing a conflagration of circumstances that mean it will be committed to spending more as a country on healthcare, particularly with a population living longer and the consequences of a two-year (or maybe more) pandemic to unpick. The question about how that spending is structured – through tax and spend, through social insurance, or through an American-style private insurance system – remains to be answered.

McCrae says how care is used by individuals will influence any policy shift from government on funding health. Engage Britain will track that relationship between citizen and state, or consumer and healthcare provider, over the coming months and years. “It’s very easy to run scare stories, but what we’re interested in is there any truth in that? As waits get longer, do we start to see [even] more people turning to private medicine? And if we see that, why is it? Is it a choice thing, or is there a way that people feel backed into a corner and have no choice?”

Attitudes, after all, can suddenly shift. There has been a significant move away from a general acceptance of other social benefits, such as employment and disability benefits, in the last three decades driven primarily by political attitudes at the top. Health leaders can’t be complacent.

One possible saviour for the NHS is that it has been forced to embrace change thanks to the pandemic. Patients who felt the draw to private digital health services for ease of access can now access these same services on the NHS free of charge. Rachel Hutchings, a fellow at the health research organisation Nuffield Trust, says Covid lockdowns demanded a rapid acceleration in plans and ambitions for digital healthcare that had been already set out before the pandemic. This is now in place for both primary care, such as GP services, but also secondary care, including hospital outpatient follow-up appointments. Whether the attractiveness of these options will persist when patients have fewer hesitations over face-to-face contact, as the fear of catching Covid-19 ebbs away, remains to be monitored, but for some the shift has been very positive.

Londoner Jennifer Vennis first registered for NHS access to virtual GP appointments via the app Babylon when she moved in with her boyfriend and the couple found it difficult to register with a traditional GP as they lived on the borders of a surgery catchment area. She had also previously struggled with chaotic telephone booking systems with her former GP practice, and decided the app “seemed like a good way to take some control back and be able to book appointments that fit my own schedule”. She describes the easy access to a virtual GP as “an amazing positive difference”, but importantly Vennis is pleased she’s able to do this through the NHS, and doesn’t have to pay for the service. Her satisfaction may be the key to sustaining a universal health service.

“Paying for healthcare seems crazy to me, and as a freelancer I’m not financially secure enough to take that on. I look at the US and other countries where you get a bill after going to the doctors and it terrifies me. The NHS needs saving somehow because there are plenty of people who can’t go private.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments