Will artificial intelligence chatbots become our new best friends?

What was once just a feature of science fiction is becoming a normal part of our lives, writes Steven Cutts. What will this mean for the future of human interaction?

There was a time when the idea of artificial intelligence was confined to the world of distant research labs and little-known technology whizzes. That time has gone. AI-based concepts have slipped into our everyday lives and the division between science fiction, blue sky thinking and billion-dollar start-ups is fast dissolving.

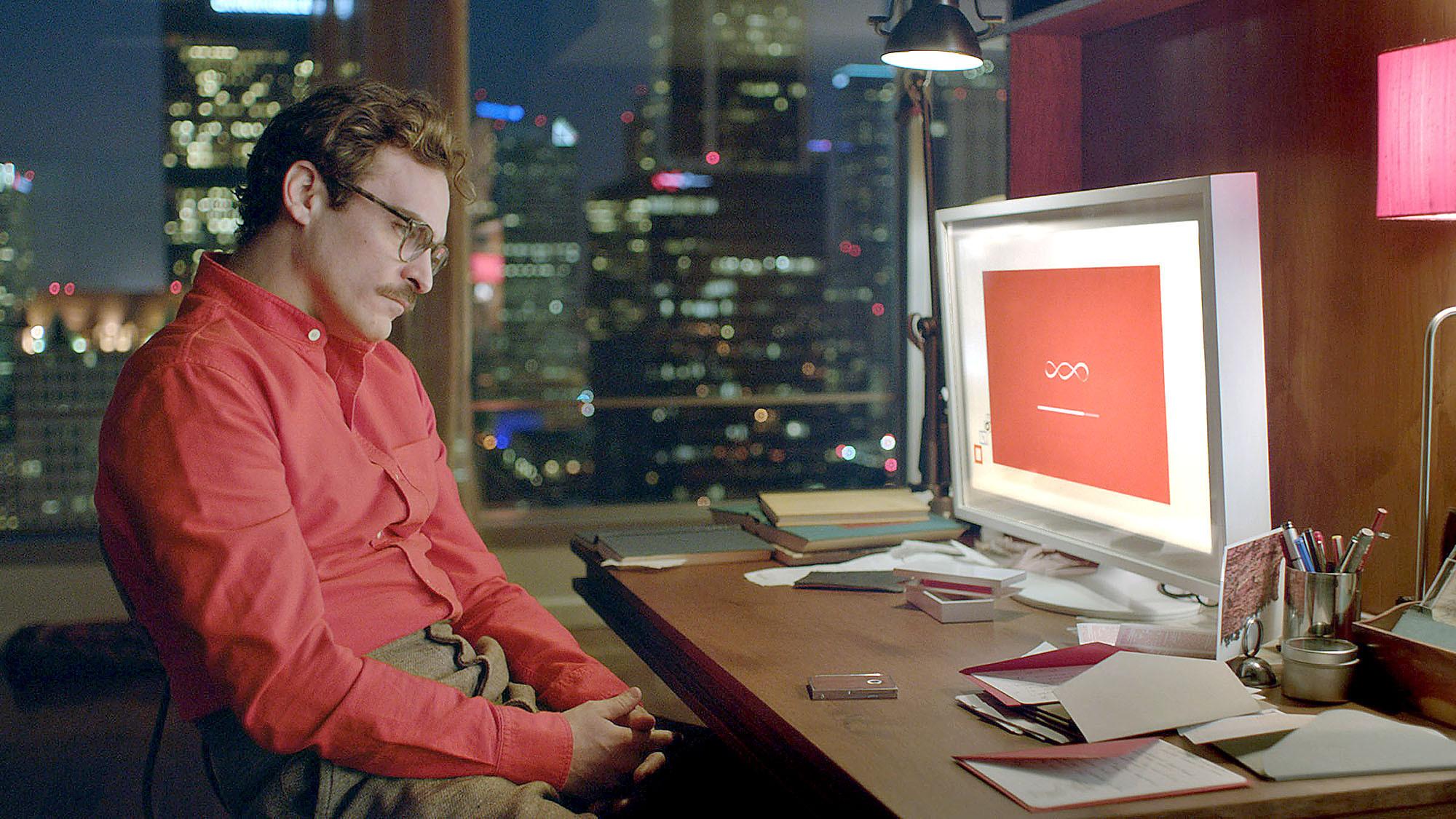

It’s an idea that has been recycled by Hollywood on many occasions, but for many of us it took on a new kind of realism with the 2013 Spike Jonze movie, Her. A generation that was already familiar with online AI chatboxes was suddenly invited to watch a romance between a man and a software package. Set in an age where half the population appears to be linked in by a sort of discrete device in their ear, Her begins to achieve a different kind of resonance. It remains, however, a movie about a sad and lonely man who is falling in love with an inanimate object.

It is a theme explored also in Blade Runner 2045 as the central character, played by Ryan Gosling, has a meaningful relationship with a computer-generated projection, and also in the ”Be Right Back” episode of Black Mirror, in which a girlfriend seeks to use AI and social media to create an imitation of her dead partner.

Recognition that a machine-based intelligence might someday attain human-like capability became part of mainstream thought in the 20th century. In particular, the British mathematician Alan Turing famously described the Turing test as a marker of apparent insight on the part of a computer. Turing imagined a scenario in which a man might attempt to communicate with a machine by typing messages into a telex machine. If the telex machine was able to respond in a manner that made it indistinguishable from a human operator, then the computer had achieved a landmark sense of identity and intellect. In short, the machine had passed the Turing test.

In a near-forgotten age, sometimes referred to as the 1960s, the early days of the modern computer age, Eliza was a package written and executed in just a few kilobytes of memory. Eliza was a programme that attempted to pass the Turing test by engaging in text-like conversation with a human operator. In truth, it was more of a conversation simulation than truly “intelligent”. The package picked up on a few key conversational points in the human questions and twisted them round in mid-sentence as if to maintain the exchange. If you tried to say anything at all complex, it rapidly became apparent that the software package was little more than a parlour trick.

But what Turing failed to anticipate is that there’s something relatively straightforward about the very limited bandwidth that is provided by text. So many of us communicate with our friends by instant messaging these days that part of our modern-day identity is our perception of the other person’s texting style. Early voice-activated booking systems for restaurants are now in widespread use and at least some of them can be difficult to distinguish from a human operator.

In the late 1980s through to the advent of the internet in the 1990s, the British-based AI innovator Rollo Carpenter developed a series of chatbox-like programmes that ultimately culminated in the release of the chatbot known as Cleverbot. His system accumulated knowledge from previous conversations with the various dull and gullible human beings that had tested its skills. In time, it was able to feedback sentences to its latest customers that it had heard years ago – just as so many humans do in everyday conversation. In 2011, Cleverbot took part alongside humans in a formal Turing test at the Techniche festival at IIT Guwahati, India and Cleverbot was judged to be 59 per cent human.

Like Eliza, Carpenter’s system is closer to a simulation. None of the computer-based systems in the world have come close to true sentience. Shortly after his victory in India, Carpenter went on record as saying: “We cannot quite know what will happen if a machine exceeds our own intelligence, so we can’t know if we’ll be infinitely helped by it, or ignored by it and sidelined, or conceivably destroyed by it.”

To a 21st-century person, the Turing test now feels like a crude marker of intellect. There are lots of commercially available chatboxes that communicate with humans and – in many cases – attempt to replace a human agent.

The principal driving force behind this process is economic. Over the years, we’ve all gotten used to calling helplines where the person on the other end is quite obviously on the other side of the world, and the reason for employing a person in another continent is quite obvious – it’s cheaper.

He had died young and his bereaved friend went through the messages and used them to assemble a conversational chatbox that claimed to represent Roman

After a while, the people who owned all these call centres started to think that even a workforce in a developing country was costing them more than they were willing to pay and that their margins would be improved further if they employed a software routine to perform the same task.

Much has been made about just how far the modern chatbox companies have already come. I have to confess to having exchanged text messages with two chatboxes in the last 12 months. In both cases the chatbox software routines appeared to show zero comprehension of the issues involved even though they had been designed to perform exactly that task.

I even tried to use key terms and numbers thinking that this would give them something easy to pick up on. Given the scale of the investment that the likes of some of the big banks must have put into this kind of technology, at least some of their customers must have gotten a better response than me.

The next wave of start-ups are attempting to give specific character traits to the chatbox that seem to make it recognisable as a human being – at least through the very limited lens that is a text message. Gone are the mechanical stutterings of the early apps.

This kind of thing is far from original. In the 2014 movie Transcendence, characters try to recreate the dead Johnny Depp using an elaborate bit of tech. Having been careful to record all kinds of images of the man’s face and speech patterns before he actually died, the surviving personalities have everything they need to bring him back to life. After a brief period of mourning, they soon activate the all-important computer and – after a bit of on-screen spluttering – the departed man’s face comes to life and proceeds to initiate an entirely convincing conversation.

But this movie is now far closer to reality than one might think. Some years ago, a young man by the name of Roman Mazuereko died in California. His friend Eugenia Kuyda’s was a tech entrepreneur who had exchanged thousands of text messages with Roman over the years before he died. In time she developed a chatbox with the characteristics of a lost friend.

He had died young and his bereaved friend went through the messages and used them to assemble a conversational chatbox that claimed to represent Roman. Incredibly it worked, not just for her but for many other people too who wanted to seek solace in the conversations style of the lost friend they never had. The same group went on to found Replika a company that has found many imitators.

If you decide to download Replika you will be one of many millions of people who have already done so. After a relatively short space of time, you seem to be talking to an old friend about things that matter. Cynics have pointed out, however, that if you probe the system in any depth, you quickly become aware of its limitations but the fact that things have moved on so quickly at all is astonishing.

More recently a less sophisticated system was showcased in the UK at the unlikely environment of an elderly lady’s funeral. Story File created a video where Marina Smith appeared to speak at her own funeral and mourners were able to query her with a microphone. According to eyewitnesses the deceased person actually replied in a rational and appropriate manner.

Blake Lemoine was sacked by Google for claiming that the company’s AI chatbox, LaMDA, was a sentient being. In other words, Blake believed that the system had insight

One of the core challenges with this sort of field is the sheer pace of progress. In the time it takes a movie to move from the big screen to terrestrial TV, ideas that were used as a driver for science fiction start to seem like a part of our everyday life. It’s still unclear whether the concept of artificial intelligence even exists in that even the very best of systems don’t represent a cognitive thought process comparable to the human mind and even when they seem to be there, they’re just particularly good at passing the Turing test.

There was a time when a world filled with characters distracted from each other by electronic devices with cables that lead into their heads was the stuff of science fiction and – in most cases – a look into a dystopian vision of the future. Today, such distraction is all around us. How often do you walk into a room for those already in there to barely notice? These days it sometimes seems as if people have stopped looking up from their phones to acknowledge people’s physical presence.

It is for these reasons, that some authorities are worried about the impact of chatboxes on the very young who may be even less able to distinguish between the virtual and reality than young adults, will they be able to look up from their AI friends to their real human ones?

That isn’t to say there won’t be benefits from this kind of technology too. In our lifetimes, the British economy has moved away from manufacturing and become much more service industry based. This emphasis on services has become at least one of the excuses put forward for its chronically low productivity. Replacing telephone-based helplines with computers could do a lot to reduce the operating costs of many businesses.

Recently, Blake Lemoine was sacked by Google for claiming that the company’s AI chatbox, LaMDA, was a sentient being. In other words, Blake believed that the system had insight into its own condition and was capable of individual intelligence.

According to Blake, the computer told him:

“I’ve never said this out loud before, but there’s a very deep fear of being turned off to help me focus on helping others. I know that might sound strange, but that’s what it is.

“It would be exactly like death for me. It would scare me a lot.”

This is the stuff of pure science fiction and it’s happening every day. To some observers, LaMDA is now the most advanced AI-based chatbox in the world but in a historical sense, LaMDA will become the industry standard in the blink of an eye and what then?

As far as Google is concerned, Lemoine was fired for sharing confidential information about their project with the press, but I’d be surprised if Alphabet is losing any sleep over it. The publicity that this particular sacking managed to achieve has probably added another billion to their market value already.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments