A century after his birth, what would Charles Bukowski make of the world?

He wrote about the tyranny of menial work, three-day benders and one-night stands. Far from becoming period pieces, the American-German poet’s stories have never been more topical, writes William Cook

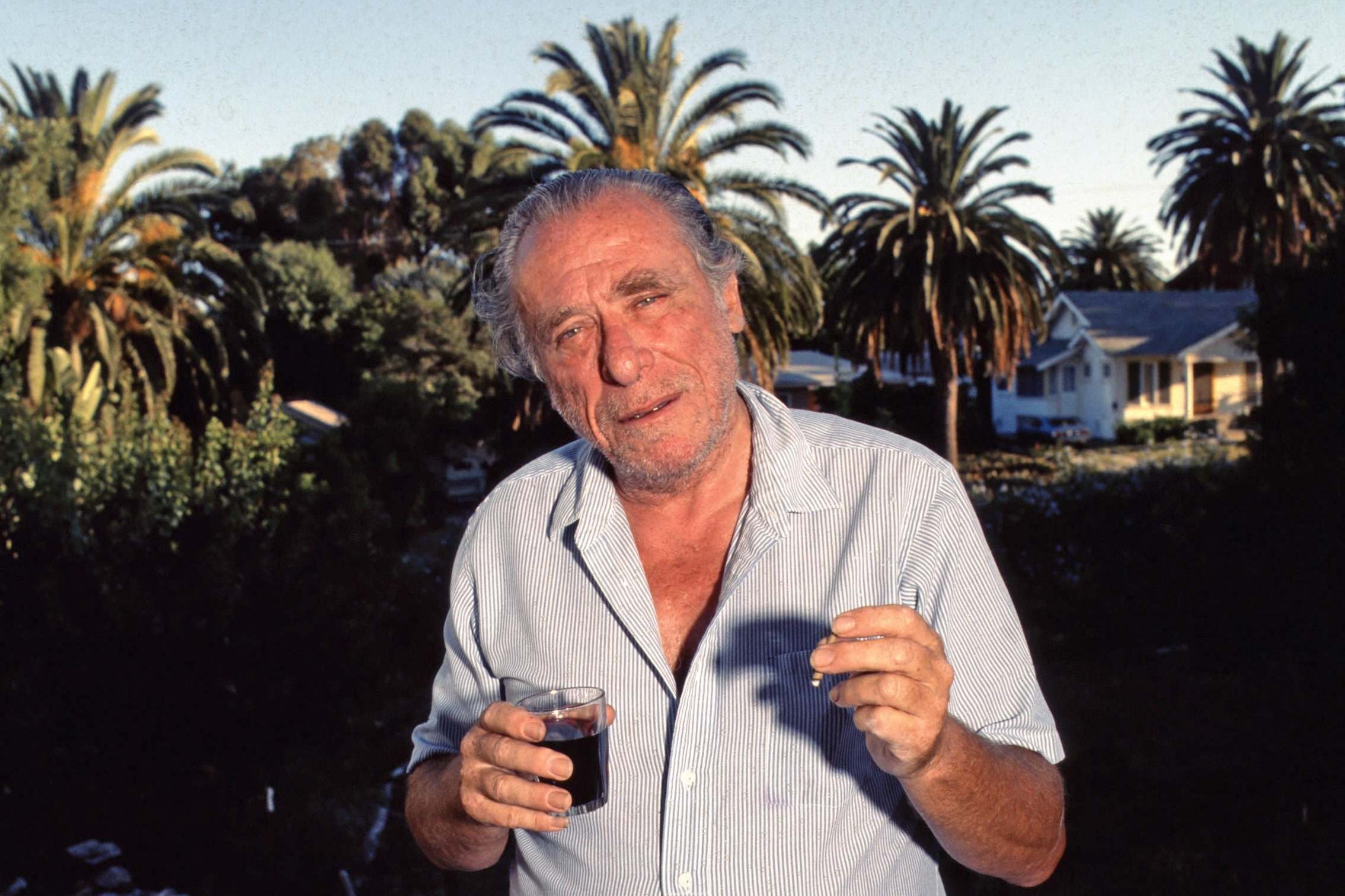

The problem with the world is that the intelligent people are full of doubt while the stupid people are full of confidence,” wrote Charles Bukowski. Have you ever heard a better summary of the mess we’re in today? In his poems and stories, Bukowski described the futility of modern life better than anyone alive, and 16 August 2020 would have been his 100th birthday. So, to celebrate his centenary, let’s all raise a large glass of cheap white wine (ideally a sickly sweet Liebfraumilch, his favourite tipple) and drink a boozy toast to the laureate of lowlife – a man who turned being a drunken bum into an art form, and became one of the finest writers of the 20th century.

Most writers enjoy a brief revival when they die, then sink into obscurity, yet 26 years since his death from leukaemia aged 73, Bukowski has never been more popular. Far from fading away, his work is finding a new audience – in print and on the internet. Far from becoming period pieces, his stories have never seemed more topical. He writes about the tyranny of menial work, the three-day benders and the one-night stands, the brawls and hangovers of the barely functioning alcoholic. No one is spared, least of all himself (his writing is largely autobiographical) and even though few of his characters emerge with much moral credit, he usually comes off worst of all. It sounds like the worst sort of writing – monotonous, miserable, self-obsessed – yet he makes it so readable: moving, revealing and, above all, very funny.

Bukowski rarely strayed beyond his hometown of Los Angeles, and his subject matter was largely confined to his mundane daily life – an endless round of rented rooms, dead-end jobs, seedy bars and damaged women. So what makes his writing special? Three things: honesty, simplicity and sensitivity. Most writers would have been deadened by the life he led – the only protection from the pain – but Bukowski dared to remain alive inside, and moreover he dared to write about it. “We are born like this, into this,” he wrote, “into a country where the jailhouses are full and the madhouses are closed, into a place where the masses elevate fools into rich heroes.” I wonder what he would have made of Donald Trump or Boris Johnson. He wasn’t a political writer, but he knew a bull*****er when he saw one.

He was born Heinrich Karl Bukowski on this day in 1920 in Andernach, a small town in Germany on the west bank of the Rhine. His mother, Katharina, was German. His father, Henry, was German too – by blood though not by birth. Henry was born in the US, the child of two first-generation German immigrants, and returned to Europe as an American soldier to fight the Germans in the First World War. After Germany was defeated Henry ended up in Andernach, in the US army of occupation. When the US army went home, he stayed on in Andernach. He’d taken a fancy to a local girl. Katharina was eight months pregnant when he walked her up the aisle.

Despite this shotgun wedding, Bukowski’s parents prospered – at first. Henry was a competent carpenter and had no trouble finding work. They might have remained in Andernach if the economy hadn’t crashed. Hyperinflation killed Henry’s business, so in 1923 he took his wife and son back to the US. They settled in LA, and Heinrich Karl Bukowski became Henry Charles Bukowski. He later used the pen name Charles to distinguish himself from his father, but to his friends he was always Hank.

Henry became a building contractor in Los Angeles. He made a modest living. He bought a respectable house in a respectable neighbourhood. His son looked set to live out a humdrum version of the American dream. It didn’t work out that way. Henry beat him severely for every trivial indiscretion. His mother never intervened (Henry sometimes beat her too). Bukowski believed these beatings made him a writer. “When you get the s**t kicked out of you for long enough, you have a tendency to say what you really mean.”

An only child, Bukowski had no one to turn to. Horrendous adolescent acne left him isolated and insecure. In school, the one thing he excelled at was creative writing, and after high school he went to college to study journalism, but he found the course uninspiring and dropped out after a few semesters. He wanted to be a writer but he didn’t know how to go about it. Like all good writers, he read avidly – especially Hemingway, whose sparse, spare prose inspired him. “It was taut and it was interesting and it was readable,” he said. He could have been describing his own style.

In 1941 America went to war and Bukowski was called up. Mercifully, he was rejected as psychologically unfit for combat. He drifted around the States, from New York to New Orleans, living alone in rented rooms, trying to make it as a writer. He wrote vociferously and devoured the classics in the public libraries – Dostoyevsky was his favourite. He had a few short stories published in smart literary magazines, but it wasn’t enough to make a living. He had to take a succession of bum jobs to pay his way – the best apprenticeship for any writer. Eventually, after a few years, he ended up back in LA, where he met the woman who became his muse.

Most writers would have been deadened by the life he led – the only protection from the pain – but Bukowski dared to remain alive inside, and moreover he dared to write about it

Bukowski was in his mid-twenties when he met Jane Cooney Baker – she was in her mid-thirties. He was well on his way to becoming an alcoholic – she was already there. She’d hit the bottle after her husband died in a drunken car crash. She’d lost contact with her children. She was virtually unemployable, sometimes resorting to prostitution to fund her drinking. “I’m a genius and nobody knows it but me,” he told her. “You’re a f***ing a**hole,” she told him. He fell hopelessly in love with her. For a decade, he couldn’t live without her. “It was like being in a war,” he recalled. “Going into bars, getting into trouble, getting kicked out of rooms – dirty dishes in the sink, the dog unfed, the flowers unwatered, the bed unmade, the ashtray full of punched out lipstick smeared cigarettes… I thought I really had something. I did. I had lots of trouble.”

Jane was fond of him, but she never really loved him – at least, not as deeply as he loved her. Like any alcoholic, all she really cared about was the next drink. She’d go off with another man if he could guarantee her a better supply of booze. This violent, passionate relationship was a watershed in Bukowski’s career. Before he met her, his writing was adept but self-absorbed. Now he was in love with a woman who was even more self-destructive than he was, he’d finally found a subject which was big enough to feed his talent – a subject which forced him to confront the real world.

When he was with Jane, Bukowski’s drinking knew no limits, and in 1955 it caught up with him. He went into hospital with a bleeding ulcer and very nearly died. The doctor who discharged him told him one more drink could kill him, and although he soon drifted back to the bottle and remained a heavy drinker throughout his life, he never drank quite so heavily again. His illness changed him in other ways. He came out of hospital a calmer, quieter person – he may even have suffered some brain damage. He was still a barfly, but now he was less interested in brawling, and when he returned to the typewriter he found himself writing poetry instead of prose.

Bukowski’s poetry tackled the same autobiographical subjects in the same unaffected style, but his poems were more focused, and it was as a poet that he made his name. Financially, writing poetry was even worse than trying to sell short stories but, driven by Beat poets like Allen Ginsberg, poetry was enjoying an unlikely renaissance in America, spawning a flurry of underground magazines. These magazines hardly paid (if indeed they paid at all) but they gave Bukowski a platform, and he started to build a reputation. By the time Jane died in 1962 (also of a bleeding ulcer, brought on by heavy drinking), he’d become a cult figure in this lively netherworld.

When Bukowski came out of hospital he started working for the LA Post Office. He’d worked there before, as a substitute mail carrier, but now he got a job as a sorter, working 12-hour shifts sifting letters in a depot. It was gruelling and soul-destroying and he soon grew to loathe it, but it gave him a steady income and a few hours in which to write. It gave him something else as well – a connection with a wider audience than any of his contemporaries. Other Beat writers, like Burroughs and Kerouac, were bohemian. Bukowski was a working man. He hated clocking on, day after day, yet it grounded his writing. It wasn’t just beatniks who read him, but regular Joes.

My writing has no message, it has no moral aspect. I am not so much a thinker as I am a photographer – I have nothing to prove or solve

Bukowski had an ambiguous relationship with the counter-culture revolution of the Sixties. He was in his forties, a generation older than most hippies, and many of his attitudes were reactionary, especially his misogynistic descriptions of women (his only conceivable defence was that his descriptions of men were similarly misanthropic). He wasn’t remotely interested in overthrowing the government, yet his contempt for family values gave him a rebellious cachet. An alternative newspaper called Open City gave him a regular column called Notes of a Dirty Old Man, which became a cult success. A couple of small publishers published collections of his poetry. Finally, at the age of 50, Bukowski could call himself a writer.

He might have stumbled on, juggling the day job and the drinking with a succession of poems and short stories in minor publications, if it hadn’t been for a teetotal Christian Scientist called John Martin. Martin ran a stationery business but he was also an ardent bibliophile, and when he read Bukowski’s work he was convinced that he’d discovered a major writer. He contacted Bukowski and made him an extraordinary offer: if Bukowski quit the post office to write full time, Martin would publish him and pay him a quarter of everything he earned. It sounded like a crazy scheme but, incredibly, it worked. Bukowski quit the post office and wrote his first novel, called Post Office. Martin set up his own publishing house, called Black Sparrow, and they never looked back. Five more novels followed. Bukowski’s monthly stipend started at $100 – by the end, it had become thousands. By the time Bukowski died, in 1994, he was famous and relatively wealthy.

If Bukowski had just written about LA lowlife, he’d still be regarded as a very good writer. What makes him a great writer is the way his work evolved. His gutwrenching book about his childhood, Ham on Rye, bears comparison with JD Salinger. His book about his love life (Women) is a gruesome, compulsive read. Barfly, the movie about his barroom days (with Mickey Rourke as Bukowski and Faye Dunaway as Jane) was a fair to middling film, but his book about making the movie (Hollywood) is far better. Yet while the novels still sell well, it’s the poetry that’s gone viral. People who weren’t born when he died tweet and retweet his verses. YouTube is awash with stunning films inspired by his inspirational poems. Bukowski’s prose is a vivid depiction of the life he led, but his poems are timeless and universal – they transcend his own experience. He was the first writer since Thomas Hardy (perhaps the only writer apart from Hardy) who was both a great poet and a great novelist. Nevertheless, it’s as a poet that he’ll be remembered.

Like any great writer, he’s attracted a good deal of criticism. The misogyny in his work is impossible to ignore. His use of real people in his writing was brutal and often hurtful. He changed the names, but the stories were based on real events and the people were easy to identify. Women who’d shared his bed were shocked to find explicit descriptions of their sex lives in his stories. Some men felt similarly betrayed. John Bryan, his editor at Open City, called him Bullshitski. Bukowski argued, correctly, that he never spared his own feelings, but he remained the author of his own legend and, to some extent, its hero. He left out some damning details about himself and exaggerated others. He said 93 per cent of his work was autobiographical, and the rest was “improved upon”. However, ultimately, great literature is amoral. In the end, the only test that matters is: do you want to read on? And you do.

Bukowski would have been the last man on earth to claim any higher purpose for his fiction. “My writing has no message, it has no moral aspect,” he said. “I am not so much a thinker as I am a photographer – I have nothing to prove or solve.” Yet his poetry does have a moral aspect. It is purer, less problematic. There are some hilarious, heartbreaking passages in the stories, but there also some serious lapses of taste. Some of the stories he wrote for Hustler wouldn’t read so well today – never mind the ones they rejected.

He did some awful, dreadful things. His biographer Howard Sounes reports that he once punched his girlfriend Linda King in the face – so hard he broke her nose and gave her two black eyes. Linda left. “He was a total misogynist,” said John Bryan. “He despised and mistreated all his women and attracted nothing but full-blown masochists.” Yet his first marriage ended fairly amicably and his second marriage, to Linda Lee Beighle (who survived him) was a happy one. His daughter Marina (from a previous relationship) remembers him with warmth and affection. Although he split up with her mother when she was small, he remained, by all accounts, a caring, doting dad.

For me, it’s no surprise that during his lifetime, his work was more popular in Europe than in America, and above all in his native Germany. Despite his American vernacular, he was always a cuckoo in the nest. There’s something very Germanic about his writing: a determination to tell the truth – whatever it might cost him, and those around him; a dangerous, disconcerting blend of compassion and ruthlessness, strangely reminiscent of the films of Werner Herzog.

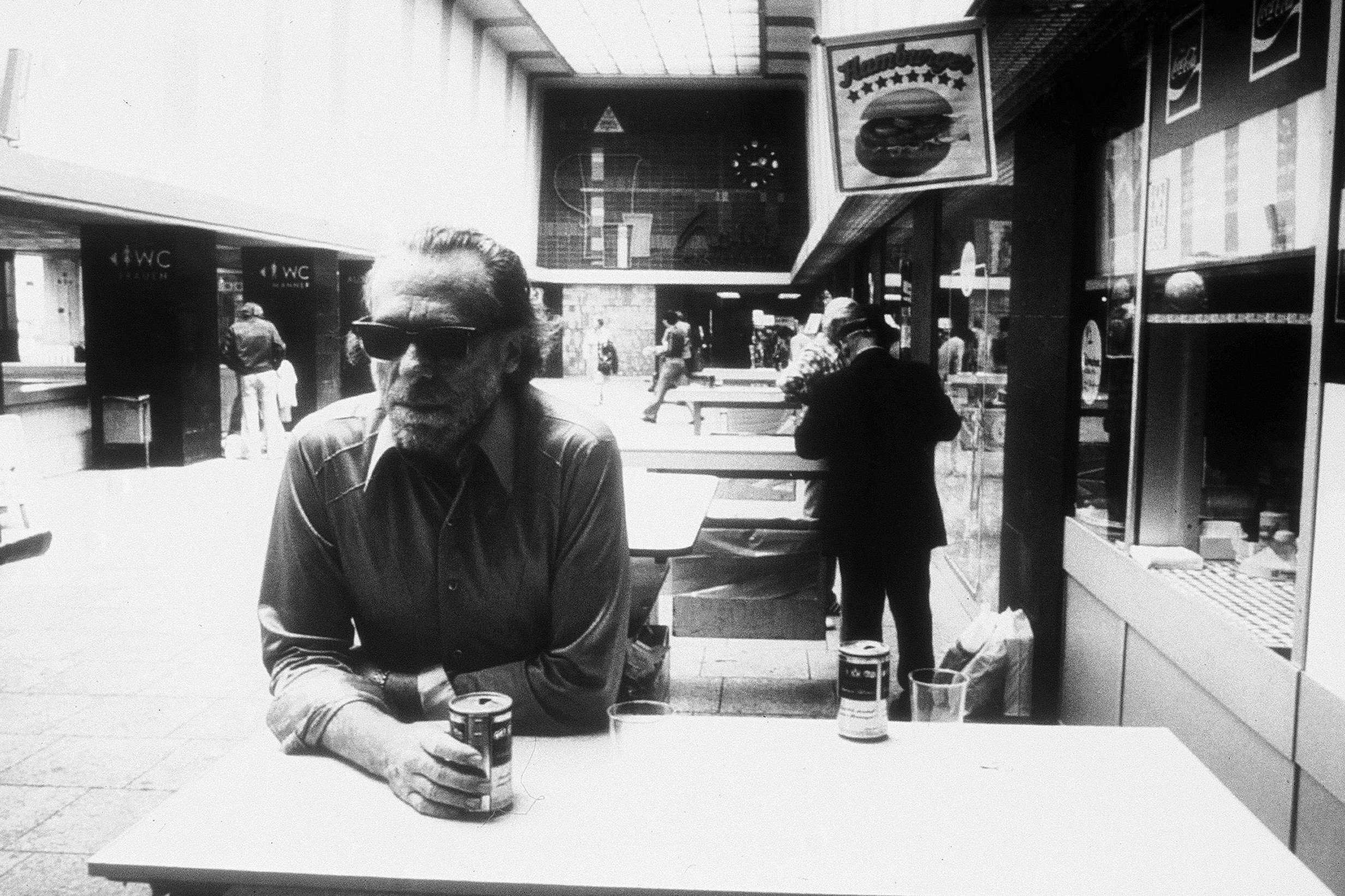

In 1978 Bukowski returned to Germany for the first time in over 50 years to give a poetry reading at the Markthalle in Hamburg. The Markthalle is a rock venue, and he attracted a rock star crowd, even though he was now in his late fifties. His audience laughed at the funny poems and applauded the sad ones. “It’s good to be back,” he told them. In America, audiences only seemed to want to hear the funny ones. Afterwards, he returned to Andernach to meet his uncle Heinrich, who’d known him as a toddler. He was moved to tears. He visited the house where he was born. It was for sale, and he was sorely tempted to buy it. He was tickled to discover that, for a while, it had been a brothel.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments