The fund helping young people who grew up in care to thrive at university

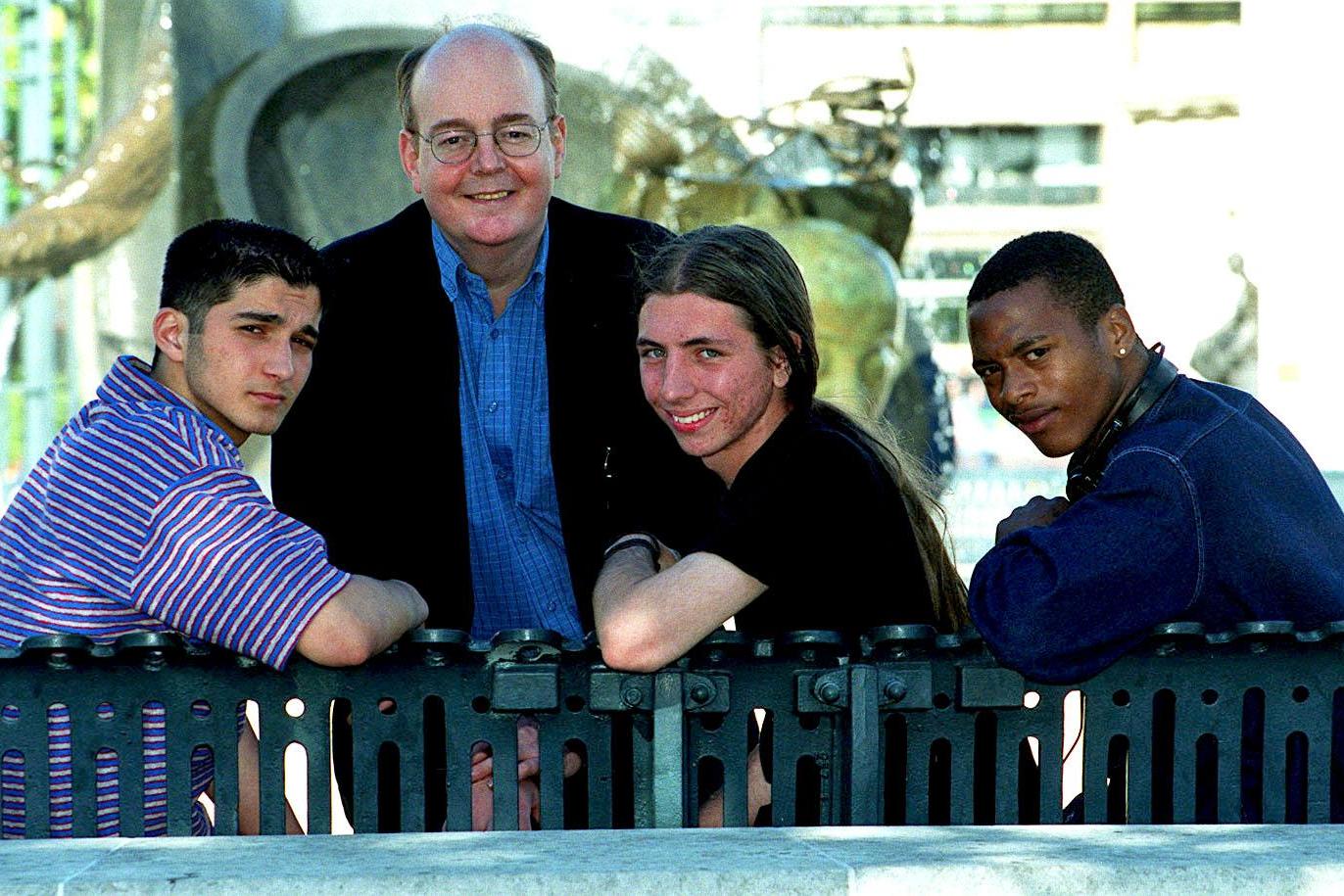

A charity in Birmingham is changing lives by providing access to higher education. Jon Bloomfield reports

Katie was abused by a close family member when she was 12. The police investigated, her mum backed the abuser and life went downhill from there. No foster placement worked out; she had 28 in all. A spell in a children’s mental health institution followed before she found some stability in a private children’s home. She was shunted from school to school but found that it offered a bolt-hole from the chaos at home, so she managed a decent set of GCSEs and then four good A-levels: “I saw education and going on to university as a way out, a chance to find myself.”

University was hard at first. “I felt so different from the others. They didn’t know how to cook; they had family to go back to. At Christmas I stayed in the hall of residence and cried a lot.”

Things improved as she made new friends, however, and gained the confidence to join student societies. She got her degree and then decided that she wanted to be a social worker. “I felt angry and bitter about how some social workers had treated me. I feel many years later how bad they were. I still have the reports under my bed. I was let down. I felt from my experience I could do better.”

The problem was funding the course. The local authority had supported her through university, with £50.95 a week for living expenses and housing costs, and she had been eligible for a student loan to cover tuition fees. But she now wanted to undertake a postgraduate degree in social work and had run out of her loan entitlement. Katie was juggling two part-time administrative jobs, which covered her basic living costs, but there was no way she could save up for the fees. That’s where the Eve Brook Scholarship Fund (EBSF) stepped in.

She heard about it through a friend on the Facebook group Care Leavers Rock, filled in the application form and then went for an interview. While the local authority continued to pay a living allowance and accommodation, the fund agreed to an upfront payment of £3,200 to cover the fees for the master’s in social work. Katie says: “I felt somebody really believed in me. They didn’t want anything in return. They were just trying to help me.”

The course went well. She qualified in 2016 and then got a post in the children’s assessment team at Southwark Council. From there, she has gone on to a more therapeutic role as a social worker for child and teenage cancer patients at Great Ormond Street Hospital. She sees her long-term future within the profession, perhaps being a manager and influencing policy and practice. “I can’t change what happened in my life but I can use it for the better. I want to help people in difficult times. I can be there for them.”

The Fund’s Purpose

Katie is just one of more than 200 young people who have been helped and supported by the EBSF. The fund was set up in 1998 following the early death from cancer of councillor Eve Brook, the chair of Birmingham social services. From a working-class family in Bradford, Eve had left school at 15 and worked for more than a decade before going to university as a late entrant.

She continued her studies in Birmingham, became a Labour councillor (the first ever in a previously Conservative ward) and then chair of social services. Before her death, she discussed with her husband, the playwright David Edgar, the establishment of a charity to help care leavers go to university. “Eve recognised herself in people from unconventional backgrounds who needed routes into higher education,” says Edgar. “We used her money and donations given at her death to establish the seed fund for the charity.”

Without Eve Brook, I wouldn’t have done the degree or got a job. It was really vital to me. I’ll always be grateful to them

The EBSF’s primary purpose is to support care leavers by helping them go to college or university and make a success of the experience. It achieves this in three main ways: scholarships that cover all or part of a young person’s fees or living expenses; postgraduate bursaries to help students undertaking master’s courses; and one-off grants to cover ongoing expenses at college such as books, travel costs and childcare for single parents. During its 21-year existence, the fund has raised and spent £326,373 on grants to more than 200 young people. In the past decade, 92 per cent of the fund’s earnings have gone directly to its beneficiaries.

Although a completely independent charity, the EBSF has worked very closely throughout with the city council and now with Birmingham Children’s Trust, which has assumed the statutory responsibility for looking after the city’s children in care, and care leavers. Edgar recalls how they met up with the after-care service from the outset and got their agreement that one of the charity’s trustees would be the director of the relevant city-council department, while social workers and after-care staff (personal advisers) would be the conduit for applications to the charity.

Sarah Barker is the after-care team manager who oversees these arrangements; informs all the city’s personal advisers about the Fund; and regularly brings a clutch of applications to each trustee meeting. She and her head of service, Shank Patel, are delighted at the practical cooperation that has helped the two bodies in their common goal of boosting the participation rates of care leavers in higher education.

“We are ambitious,” says Patel. ”We believe in young people. Our offer is good. We pay for the student accommodation of care leavers and £57.90-per-week living expenses, while the local universities are very encouraging.” The approach has helped to change the political climate around care leavers locally. This year, 110 care leavers are in higher education, about 14 per cent of the total number of care leavers in Birmingham, a figure that is over twice the national average. The numbers still lag well behind Scandinavian countries, but represent an important advance within the UK.

Who Sustains It?

The EBSF raises its money from three main sources: grants given by charities, mainly from the Midlands; individual donations and standing orders; and events such as quiz evenings, curry nights – a Birmingham staple – and jazz concerts. Edgar chairs the charity and acts as its public face, and is supported by a small band of stalwarts.

John Rouse is one of them. He was an election agent for Brook when she first became a councillor and has been heavily involved in its work for the last decade. As the treasurer, he manages the accounts, makes applications to other charities and ensures that the charity is run as a tight ship. “We take no expenses,” he proudly tells me, which means that almost all the money raised goes directly to support beneficiaries.

Care leavers often attend the social events and their delight is evident at these gatherings. At a recent event at the Ikon Gallery, Kim told about the Sky Dive she was to undertake as part of the charity’s 20th-anniversary fundraising activities and what the fund meant to her. She’d been moved from an unhappy family situation into foster care when she was 13. “I should have been moved into care much earlier. I kept running away from home.”

The charity also serves as an antidote to those pundits who claim that the professional middle classes – often pejoratively termed the “metropolitan elite” – are selfish and have no interest in those who are worse off than themselves

She moved around a lot over the next few years, which didn’t help her education – and neither did the bullying when other kids found out she was in care. “I was lucky that my nan fought the social services so that they provided a tutor for me at my foster parents’ home and the school would send home the coursework I had to do.”

She passed nine GCSEs and, despite continuing problems at a new school and with her social worker, she passed three A-levels and went to Manchester Met to do drama and English. Even with a really supportive after-care worker – “she was amazing, I’m still in touch with her” – university was difficult. “I made the wrong kind of friends; got into an abusive relationship; in the summer, everyone went home and I had nowhere to go. I got dumped into a social services half-way house which was awful.”

At the end of her second year, Kim was determined not to repeat that experience. She wanted to go abroad, so she applied for a summer camp in Ontario that catered for people with extreme behaviours. The after-care worker told her to apply to the EBSF, which agreed to pay for her flights, while the camp provided board and lodging. “I was knocked unconscious on my first day by one of the pupils, but being on the camp for three months completely changed me. I learnt how resilient I was. I came back, walked away from my abusive relationship, did a great module on directing, and ended up with a 2:1.”

She then won a place to do a classical theatre master’s at Kingston University. The fund gave her personal support and encouragement before her interview and agreed to cover the tuition fees for the course. Since her graduation in 2013, Kim has done a range of short-term placements, jobs in the cultural sector and is currently the arts project coordinator for the Rees Foundation, a national foundation based in Redditch that works with care leavers aged 16 and upwards. “I’m the one-person arts department,” she observes wryly. She loves the job, developing art and poetry exhibitions and displaying the work of those who have been in care across the Midlands and beyond, and she has several new projects on the go.

The Diversity of Care Leavers

The care leavers supported by the charity go on to a wide range of courses. Edgar says: “We’ve had people going into law, engineering, social policy and a strong strand in the performing and creative arts.” The care leavers reflect the demographics of the city. Breakdowns occur in working-class and middle-class families, affect girls and boys, and are to be found in migrant and refugee households. Over the last six years, about half of the EBSF’s beneficiaries have come from black and ethnic minority households.

Amir comes from a Muslim family from Pakistan and has just completed a master’s in screenwriting at the Met Film School in London. He fell out with his parents as a teenager when he rebelled against the devout religious beliefs that they wanted to impose on their son. He went to a hostel and then a semi-independent home before his father attempted a partial reconciliation. Amir continued to receive support from an after-care worker who told him about the fund when he sought to pursue a postgraduate course after his degree in English and creative writing. “The fund for equipment, books and travelcard were the crucial extras that I needed.”

David came as an asylum seeker from west Africa as a teenager. The immigration service put him into care in Birmingham, where he attended college. He was granted “discretionary leave to remain”, but in 2007 this meant he had no access to the university student-loan system. Told about the fund by his social worker, he applied to EBSF and they agreed to pay the tuition fees for his course in mechanical engineering.

This fund changes people’s lives. I’ve known no beneficiary who doesn’t feel the same way. These are people who are willing to invest in you; who show faith in you

He then got a job with a Birmingham engineering company that makes components for the aerospace and automotive industries, and where he has progressed to be a technical engineer undertaking project management. “The company has been good to me.” After two years, he won a place on a part-time engineering, business and leadership programme at Warwick University where the company covered his fees, while he also applied to EBSF for a range of support with the course, including study materials and travel costs.

He is conscious of the profound impact the EBSF has had on his life. “Without Eve Brook, I wouldn’t have done the degree or got a job. It was really vital to me. I’ll always be grateful to them. That’s why I always do what I can to support the fund.” His social worker had been excellent, always very helpful, and he was pleased that he was recently asked to give a talk at a care leavers’ conference. It had gone well, with plenty of good feedback. “I’m just giving my experience back to others.”

The extra support that the charity can offer proved invaluable to Kerry. She had to cope with the challenges of a disrupted childhood. She was the eldest of nine children fathered by seven different men. Her mum was never in a position to parent and Birmingham’s social services were in regular contact with the family from a young age.

At 14, Kerry was placed in foster care with parents who offered stability through her teenage years. Naturally good at school – like Katie, she found it a relief from home – she did a history degree at Sheffield and then looked to do an MA in development in London. Alerted by her after-care social worker, Kerry applied to the EBSF for an annual transport pass. “This was hugely important. The ability to have all of my travel costs covered, to get to lectures, see cultural aspects of London and visit friends was invaluable. It enabled me to stay connected and overcome the barriers of isolation.”

Following her master’s, she got a job in health and wellbeing and then moved into public health where she is currently the lead policy officer in the London borough of Hackney. She still recalls how the fund helped her and others. “People forget about all the opportunities and access that people miss when they are in care. The fund makes things a bit easier; it takes away barriers; it fills a gap for care leavers.”

The Wider Significance

The fund does invaluable work for the individuals it supports, but the initiative also has a wider political resonance. The former prime minister, David Cameron, spoke a lot about “the big society”, but his idea was more about civic initiatives acting as a replacement for state or local government services. EBSF is a civil-society partnership mobilising the goodwill and commitment of local citizens, mainly drawn from the professional classes, to support those in difficult circumstances.

Yet, it doesn’t seek to replace the local council or to substitute for its work, but rather acts as a complement to it. It provides additional support and encouragement to the care-leaver services. As Patel puts it: “We have shared values and awareness of the doors that educational experiences can open up. The value that the scholarship fund brings to our work is absolutely immense.”

The charity also serves as an antidote to those pundits who claim that the professional middle-classes – often pejoratively termed the “metropolitan elite” – are selfish and have no interest in those who are worse-off than themselves. EBSF stands as a living rebuke to these assertions. It is an initiative rooted in the “liberal left” and, as John Rouse puts it, “we fit into an agenda of inclusion. We counteract the negative stereotypes; the idea that if you’re in care you’re written off.”

Looking to the Future

As with all small-scale civic initiatives, the EBSF knows that it cannot rest on its laurels. So the charity is broadening its work in several ways. Firstly, from last October it has inaugurated a new policy strand whereby the fund gives a £100 book token to all Birmingham care leavers starting undergraduate courses. Edgar says: ”We see this as an act of practical support as care leavers begin their studies. It’s what a parent would do.”

Secondly, it is looking to former care leavers and fund supporters to help with the mentoring of current beneficiaries. “We are looking to volunteers who will be ‘Friends of the Fund’ and help support beneficiaries, sometimes with advice about university life, sometimes on course content.” More ambitiously, the fund intends to explore the potential to provide for care leavers who want to undertake apprenticeships rather than higher education as the route from care to a career.

After two decades, Edgar is aware that “these leavers do not want for motivation. They may lack experience and resources and we can help with that.” A lot of hard, detailed work is put in by the fund supporters, but Edgar says: “I love it, I’m very proud of it and Eve would be too. It’s a wonderful way of keeping Eve’s memory alive and her focus on young people in care.”

The beneficiaries certainly feel the same way. Among the care leavers who have benefited from the EBSF over the last two decades, the sense of gratitude is palpable. Kim has no end of praise for the charity. “This fund changes people’s lives. I’ve known no beneficiary who doesn’t feel the same way. These are people who are willing to invest in you; who show faith in you.” As Katie puts it: “When I go to work in the morning, I think that I’d never have been able to have this job without them. They believed in me. They committed and invested in me. They changed my life.”

Readers wishing to support or donate to the Eve Brook Scholarship Fund can visit its website here. Jon Bloomfield is the author of ‘Our City: Migrants and the Making of Modern Birmingham’, £18.99 (Unbound)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments