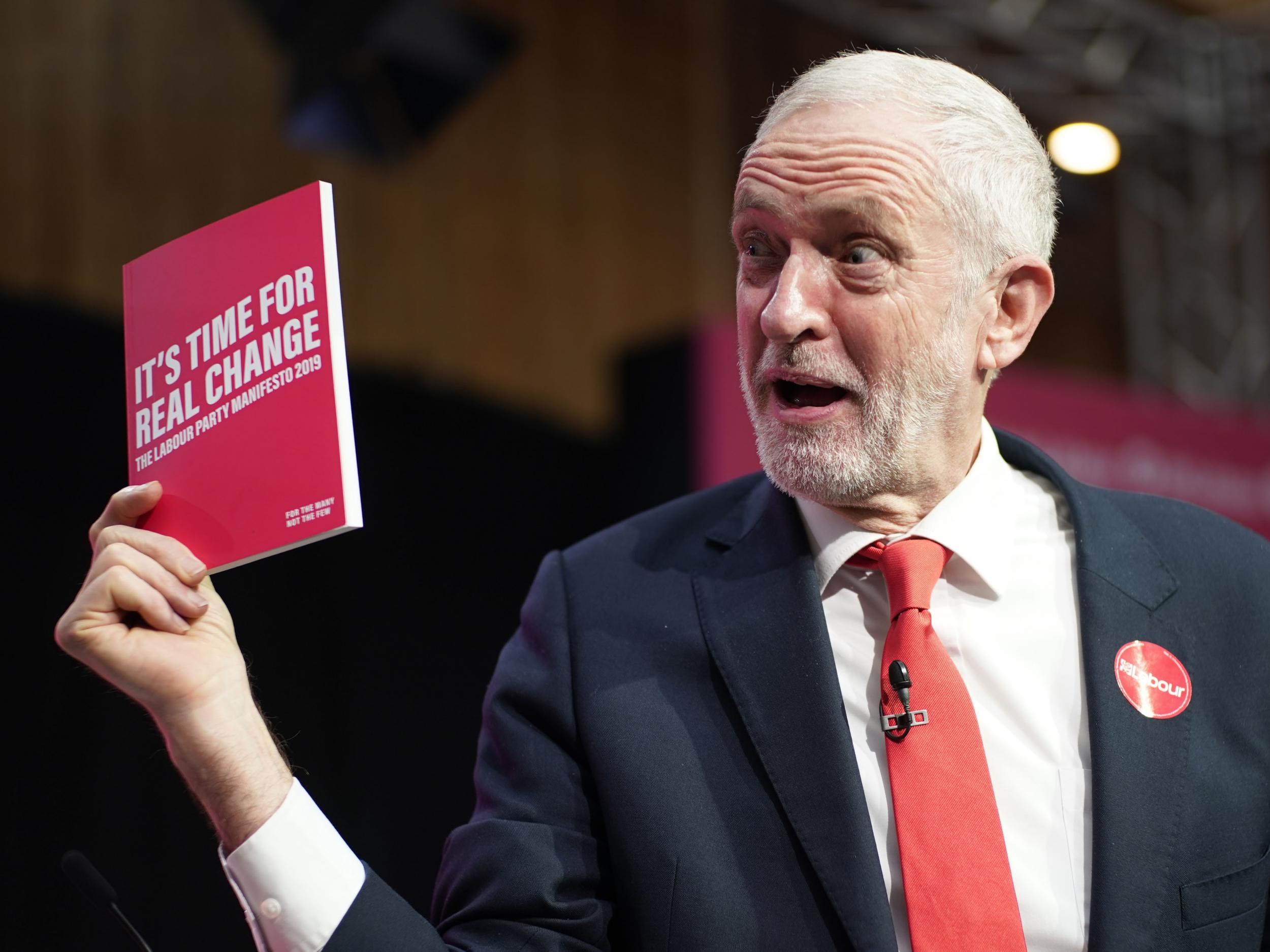

Labour’s war on capitalism was futile without a real alternative

While Corbyn shared a popular suspicion of free markets, he had only the vaguest idea of what the Labour Party should offer instead, writes John Rentoul

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A consensus is forming that Labour’s policies at the election were popular – it is just that there were too many of them; or that the party couldn’t be trusted to deliver them; or that Jeremy Corbyn was unpopular; or that Brexit was too much of a distraction. It is possible, though, that Labour’s “radical” economic programme wasn’t actually popular when it came to the test. People say they want to nationalise the railways and abolish student fees, but when presented with these policies as a prospectus for an alternative government, they voted against it.

I wonder if this means something more fundamental is going on: that opposing “capitalism” is fashionable, but, when it came to it, Corbyn’s Labour had no idea whether to replace it, and if so with what, or to reform it, and if so in what way. It is possible that this election was a battle of ideas – a rare thing in pragmatic British politics – and that, despite Corbyn’s vainglorious claim to have “won the arguments”, it was a battle that Labour comprehensively lost.

People don’t vote for big ideas, but sometimes they vote for leaders who believe in big ideas. Capitalism is a big idea, and Boris Johnson and the Conservative Party believe in it. But anti-capitalism isn’t a big idea, unless the alternative is defined. Corbyn never got beyond protesting against the iniquities of the market, while John McDonnell, his shadow chancellor, who was often portrayed as a serious ideologue, never set out what Marxists would call an analysis of the economy, let alone an alternative to the status quo.

When pressed, McDonnell was practised at deflection. He would sometimes call himself a Marxist, knowing well that the term is now so broad that it includes Professor Norman Geras, who, before he died in 2013, was one of Corbyn and McDonnell’s most strenuous critics. At other times, McDonnell would play the game of claiming that Labour’s programme in 2017 and 2019 was “mainstream” and fiscally responsible. I don’t think he went so far as to describe it as “social democracy”, but many Corbynite outriders did.

Or he would use humour. In Who’s Who he lists “fermenting the overthrow of capitalism” as his hobby. Depending on who is asking, he dismisses this as a jokey reference to his love of homebrewing, or says defiantly, “Yes, I want to move on from capitalism.”

But what does moving on from capitalism mean? We were never told. The Labour manifestos under Corbyn and McDonnell promised to nationalise a lot of companies, but that would not be the end of capitalism. All the candidates for public ownership – rail, mail, energy and water – were in the public sector for the four decades after the war, and capitalism was not abolished in Britain then.

Hence McDonnell’s need to stress that, this time, nationalisation would be different. “The old Morrisonian model of nationalisation centralised too much power in a few hands in Whitehall,” he said. And yet he never explained how his model would be different, apart from vague words about workers’ control and democratisation of the entire economy.

It was left to McDonnell’s ideological enemies, such as Daniel Finkelstein of The Times, to piece together the clues from the record. In one interview, for example, McDonnell said he had suggested that Tom Scholar, the top Treasury civil servant, should read Ralph Miliband’s Socialism for a Sceptical Age to prepare for the incoming Labour government.

This was a revealing choice. Miliband, who did not believe there was a parliamentary road to socialism, wrote: “Socialism entails the coming into being of a socialised economy, in which at least the preponderant part of the means of economic activity, notably the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy, would come under various forms of public or social ownership.”

In Britain, it is time for the Labour Party to stop pretending it is going to end capitalism, and to start talking about how the failures of the market can be remedied

In the book, Miliband declares that social democracy is not “an alternative to capitalism, but a certain kind of adaptation to it. I take socialism, without inverted commas, to mean on the contrary a fundamental recasting of the social order.”

This was the vacuum at the centre of Corbyn’s Labour: that its rhetoric promised a “fundamental recasting of the social order”, while its manifesto offered little more than the reheated social democracy of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

What Corbyn’s anti-capitalist alternative lacked in specifics, it sought to make up for in scale. The sheer size of the nationalisation programme, and of the accompanying increase in public spending, seemed designed to persuade the voters of Labour’s radicalism by shocking them into admiration.

Some of the boldness was admirable, such as McDonnell’s claim (Corbyn didn’t seem to understand it) that taking such vast companies into the public sector would cost the taxpayer nothing. Broadly, this is true, in that the government would borrow the money, paying zero real interest, and acquire an asset. The net effect on the public sector balance sheet would be neutral. There would be a cost to the public purse over time only if revenues fell or costs rose – both of which would be likely, but that is another argument.

And some of the boldness made so little sense that it simply failed to compute. While McDonnell was happy to borrow for capital investment – as indeed, on a more normal scale, was Johnson – he insisted that increases in day-to-day spending had to be paid for by tax rises. The spending increases promised in 2017 were vast enough, but this time they were doubled to £83bn a year. These were to be paid for partly by higher income tax on the best-off 5 per cent of the population, but most of the money would be raised by taxing companies. This didn’t attract much attention, possibly because the sums involved were so large, but it meant that, for every £7 currently raised in tax, Labour planned to raise another £1. Two thirds of this would come from companies, and ultimately that money would have to come from somewhere else: shareholders, employees and customers.

When McDonnell was asked about this in the election campaign he refused to accept that the cost would be passed on to employees and customers: “We’ll make sure that actually the corporations themselves do not take that easy option of cutting wages or raising prices.”

Thus he rather quickly found himself with state control as the only instrument at his disposal. Instead of an alternative to capitalism, he seemed to be proposing a capitalist economy struggling to operate under a burden of heavy taxes and government diktat.

Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party wanted to offer a world transformed, but it was not serious about it. Corbyn generally stayed at the level of generalities and platitude; and sometimes also retreated to humour, once telling photographers jostling for position: “You see, under socialism you will all cooperate.” For the outriders, anti-capitalism was a kitsch pose: Aaron Bastani with his Fully Automated Luxury Communism; Ash Sarkar with her “I’m literally a communist” performance art.

The only one who was remotely serious was Owen Jones, who once wrote a good book, Chavs, about prejudice against working-class people. But he was hardly a theoretician of the socialist alternative. Paul Mason, the former Channel 4 economics editor, tried to be, with his 2015 book Postcapitalism, which had some interesting things to say about future economic trends, but dissolved into goo when it tried to describe how a non-capitalist society might work.

It is easy enough to see why capitalism is unpopular. The financial crisis and the stringency in the public finances that followed; the feeling that somebody must be to blame, and that “they”, the bankers and the rest of the 1 per cent, got away with it

Nor did the convoy of academic economists gathered by McDonnell produce any work of practical use to a putative anti-capitalist Labour government. All they managed was to underline the conventional view that there was nothing wrong with governments borrowing for investment at a time of low real interest rates. As this has now been taken up by Sajid Javid, its revolutionary shock value has been rather diminished.

It is easy enough to see why capitalism is unpopular. The financial crisis and the stringency in the public finances that followed; the feeling that somebody must be to blame, and that “they”, the bankers and the rest of the 1 per cent, got away with it. That means there is a market for fierce denunciations, and that people who talk about overthrowing “the system” or “the establishment” gain a hearing. They sound more energetic than the social democrats derided by Ralph Miliband; and in any case, had the social democrats not been in charge of the Labour government when the crash happened? (Yes, they had, and they did exactly the right things, nationalising the banks and saving capitalism from its excesses, but this is about who can sound angrier, not who is right.)

Yet do most people believe that capitalism is a single system, or a single ideology, that is imposed on them? I don’t think so. And I doubt that they think it can or should be replaced by an alternative system involving the abolition of money and private property, and holding everything in common, which is what some forms of “socialism” imply.

Rainer Zitelmann, the German advocate of free-market economics, said in his book published last year, The Power of Capitalism: “Capitalism has grown historically, in much the same way as languages have developed over time as the result of spontaneous and uncontrolled processes.” He compares socialism to Esperanto, a “planned language” that failed to gain “the global penetration its inventors were hoping for”.

Zitelmann uses the word “capitalism” as propaganda and provocation, but he is right that it is a description of the chaotic way the world has become richer, healthier and more populous than ever, rather than a system built according to an ideology. Of course, it has cultures, values and ideologies within it, but these ideologies are competing tendencies seeking to adjust the world as it is, ranging from economic liberals to social democrats. When you look for an alternative to capitalism, there is no Esperanto of economics – and if there was, it wouldn’t work. There is no “there” there.

When you look for an alternative to capitalism, there is no Esperanto of economics – and if there was, it wouldn’t work. There is no ‘there’ there

Thus the paradox of China, the most vibrant capitalist society on Earth, which still uses the language of communism at the highest level. Xi Jinping, the Chinese president, recently declared: “Capitalism is inevitably dying and socialism is inevitably winning… This is an irreversible general trend in the development of history.”

That is the kind of thing you can say only in a country that is not a democracy. In Britain, it is time for the Labour Party to stop pretending it is going to end capitalism, and to start talking about how the failures of the market can be remedied. The party needs to put behind it the woolly thinking that has clouded its judgement since the financial crisis. In 2010-15, Ed Miliband made a lot of speeches about how bad capitalism was, dividing companies into “predators” and “producers”. These paved the way for the party to elect a leader who basically thinks all private sector companies are predators.

They are all still at it, but at least they are now moving back to the economy as it is, rather than offering some dream state over the horizon.

But what about Labour’s unexpected success in the 2017 election, depriving the Conservatives of their majority? Did that not suggest that the voters did after all believe that “another future is possible”, the Corbynite slogan adapted by Keir Starmer for his leadership campaign? I don’t think so. The iron fact of the 2017 campaign was that no one thought Labour was going to win. A Labour vote, therefore, was a cost-free protest against a Conservative government whose leader had turned out to be such a disappointment that the mood of the electorate was to deny her the greater power she sought.

Of course, the 2019 election was about other things, above all Brexit, and the voters’ views of Corbyn had developed not necessarily to his advantage. But one important difference from 2017 was that the prospect of Corbyn as prime minister was taken seriously and so voters had to consider whether they really wanted his programme or not.

“I am proud that on austerity, on corporate power, on inequality and on the climate emergency we have won the arguments and rewritten the terms of political debate,” Corbyn wrote on the Saturday after the election. But on each point, the voters preferred the Conservatives’ amelioration to Labour’s radical but unconvincing change.

If there is an answer to the ills of capitalism, in my view, it is social democracy. These terms are imprecise, but Opinium asked an open question of the British public a year and a half ago: “Do you have a positive or negative view of the following political ideologies or systems?” Of the four choices, “social democracy” came top, with 46 per cent positive, 24 per cent negative (22 per cent net positive); “liberal democracy” came next, with 41 per cent positive, 30 per cent negative (11 per cent net positive).

“Capitalism” and “socialism” were both net negative, with socialism the least popular. Capitalism was 34 per cent positive, 41 per cent negative (7 per cent net negative); socialism 32 per cent positive, 43 per cent negative (11 per cent net negative).

It turned out that in the election, Boris Johnson offered something closer to social democracy than Corbyn did.

The British people sensed that Corbyn and McDonnell weren’t serious; that they didn’t know what they were doing; and that they had no idea what they meant when they said – it was the title of the manifesto – “it’s time for real change”. Let us hope that the Labour Party comes to appreciate the value of trying to make capitalism fairer and greener instead of trying to replace it with something that doesn’t exist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments