They got it right in Germany in 2020 – and in Canterbury 80 years ago – so why didn’t Boris Johnson learn this lesson?

Well-funded local authorities would have done a much better job than central government in handling the pandemic – and saved more lives. Look at how Canterbury survived the Blitz, explains Patrick Cockburn

The struggle against Covid-19 is often compared to fighting a war against a human enemy such as Germany in the Second World War. The purpose of the analogy is a morale-boosting trumpet call for the British people to show the same degree of solidarity and determination in 2020 as they did 1940-41. Rally-round-the-flag rhetoric like this inevitably contains a hefty dollop of bombast, but cynicism should not be carried too far because a genuine comparison between now and then is both possible and revealing. The most useful comparison is not about national character of the “Britain can take it” type, but between the different ways in which government and society organised themselves to face cataclysmic crises 80 years apart.

More specifically, it is worth comparing “the Blitz”, the mass German air attacks on civilian targets between September 1940 and May 1941, with the governmental and popular response to the Covid-19 epidemic since the first fatality on 5 March. The number of officially recorded deaths is coincidentally much the same in both emergencies, though they differ in length. Some 43,500 civilians died in the Blitz compared to 40,500 in the Covid-19 epidemic at the time of writing, though the figure of excess deaths is much higher at 63,500, most of which are Covid-related. One feature of the death toll is striking: the number who died in the Blitz was much lower than the government’s scientists forecast while the number of Covid-19 deaths has been much higher than predicted.

How far was this better outcome in 1940-41 the result, among other factors, of the successful way in which state and society prepared themselves to combat an unprecedented threat? Given the level of destruction inflicted by the Luftwaffe – two million homes were destroyed – the number of people killed by the bombing was far from the horrendous predictions made pre-Blitz. Fast forward 80 years and ask the same question: how far was the terrible loss of life over a shorter period in 2020 the consequence of poor judgement at the top and chaotic organisation at the bottom.

The former chief scientific adviser to the government Sir David King estimated that an extra 40,000 people have died who would have lived “if the government had acted responsibly”. Others have spoken of the fumbling response to the epidemic as showing up Britain as a failed state. This is surely an exaggeration, but it is reasonable to see Britain as a country that failed to mitigate the impact of the disease as successfully as other countries in Europe and East Asia.

An extra 40,000 people have died who would have lived ‘if the government had acted responsibly’. Others have spoken of the fumbling response to the epidemic as showing up Britain as a failed state

In the last years of peace before 1939 and the first years of war, the British government established an elaborate system of public and private shelters, early warning systems, air raid wardens, rescue units as well as organisations geared to house and feed those made homeless by the bombing. My mother, Patricia Cockburn, spent the Blitz in a deep ARP (Air Raid Precautions) bunker under Paddington in a control room charged with dispatching fire brigades, ambulances and heavy rescue vehicles in response to calls from local ARP wardens reporting on the damage. The whole of Britain was criss-crossed with organisations, broadly directed and resourced by central government but given a fair degree of autonomy, capable of reacting quickly to a German raid.

Contrast this with the notorious government failings this time round: underestimation of the impending threat; failure to procure PPE in time; closing down test and trace in March; delaying lockdown too long; sending infected patients from hospitals to care homes; a chaotic exit from lockdown; a bizarre decision to quarantine for 14 days people arriving in Britain from less-infected countries.

Many of these mistakes are specific to the present crisis, but there is one gross and avoidable error that was not made during the Blitz. A Covid-19 epidemic and mass German bombing may seem to be very different types of crisis, but they have one crucial feature in common: in their impact they are both local events. Virus and bombs alike strike at certain people in certain places in each locality. In the Blitz, authority and resources were delegated to local organisations, both long standing and newly established. In combating the pandemic, by way of contrast, the government’s response has been highly centralised, lacking in local knowledge and flexibility, and reliant on a sledgehammer one-size-fits-all approach that explains much that has gone wrong.

The value of the wartime experience can be illustrated by what happened in Canterbury, a small British city with a population of 25,000, that was the target of a particularly devastating German raid. This did not take place during the “big Blitz” of 1940-41, but a little later during the Baedeker raids, launched by the Luftwaffe in retaliation for British raids on historic German towns, in 1942.

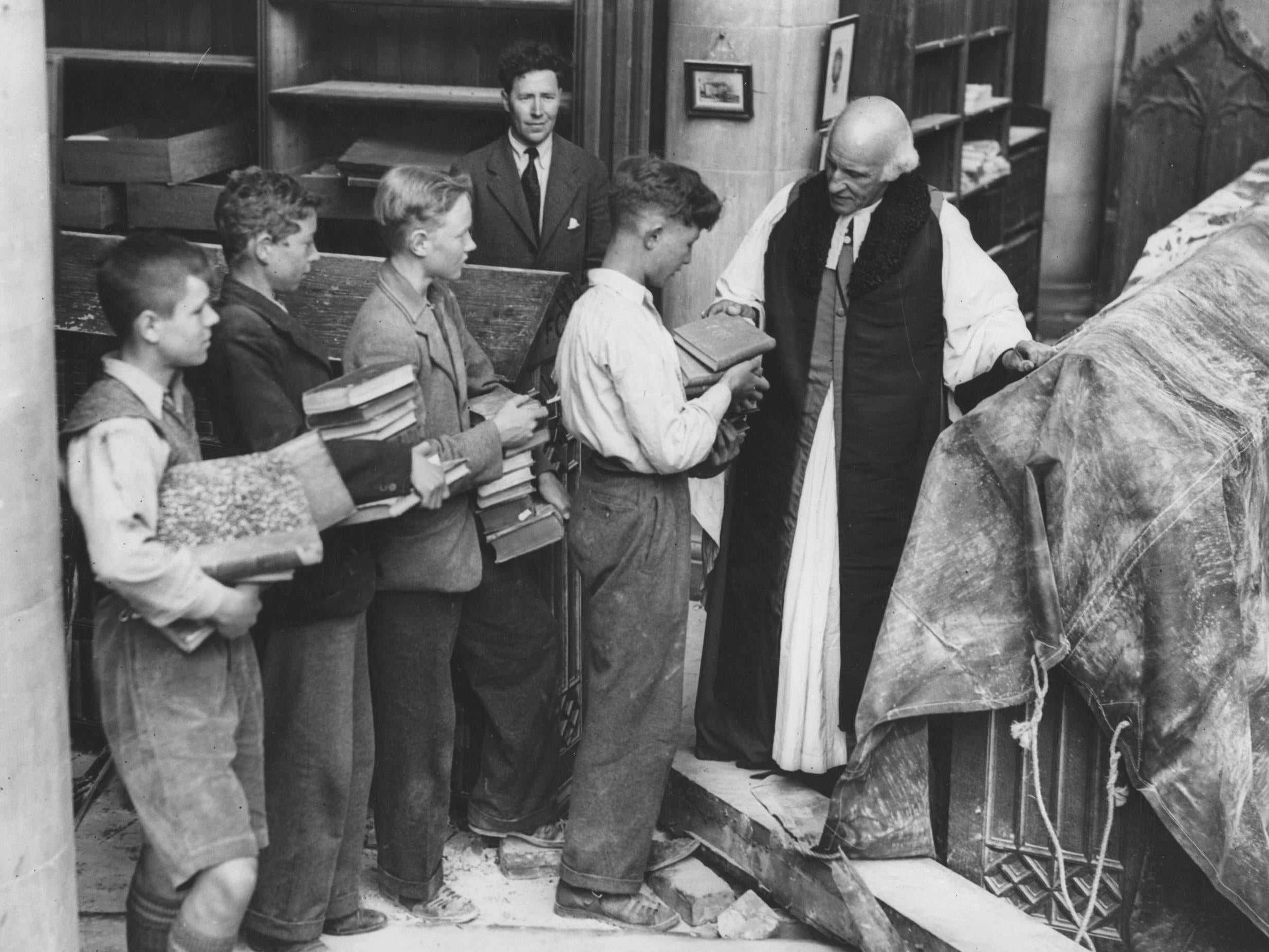

Among the ancient cities targeted were Exeter, Bath, Norwich and finally Canterbury on the night of 1 June. Much of the north and east of the city was destroyed as thousands of incendiaries and a smaller number of high explosive bombs rained down in an intense 90-minute raid. The great medieval Cathedral was only saved because its interior had been stripped of anything that would burn and heroic fire fighters perched on its roof, using metal rods and other implements to dislodge incendiaries and pitch them over the side of the building. Houses, pubs and shops were often half-timbered and burnt easily.

She was an unusual figure to be mayor of the highly conservative little city, but even her critics admitted she was highly energetic and a good organiser, as well as being convinced that war was coming

Contemporary photographs taken the morning after the raid show a seascape of fire-blackened wooden beams and shattered walls. An official report on the raid written a few days later describes how “very heavy damage had been done to the main shopping areas and also to residential property by high explosive bombs and incendiary bombs”. Listed as totally destroyed are two churches, the Cathedral library, 310 residential houses and 200 other buildings. Many more had only just survived and the report says that a total of 3,310 buildings were destroyed or damaged.

The infrastructure of the city was badly hit: “Internal telephone communications were disrupted, sewers, water, gas and electricity mains were damaged.” Some 697 people had lost their houses and were homeless. Yet the number of casualties was surprisingly low given how much of the city had been destroyed: 48 people were dead, 55 seriously injured, 62 lightly injured. The German bombers had mostly dropped incendiaries, which would have reduced the loss of life, but they had also dropped at least 100 high explosive bombs on a very small area.

An important reason why so many people in Canterbury were alive and uninjured at the end of the raid, even if their houses were in ruins, was the elaborate preparations made for just such an attack by the council of the city and its energetic Emergency Committee. They had helped build shelters inside and outside houses. Canterbury was too close to German airbases in France to get much warning of an impending raid, but the wail of the sirens did give residents a vital few moments to take cover in the shelters and there was a well-equipped rescue service.

Few details were too small for the local defence organisation: wooden ladders leading to the roof of the cathedral had been replaced with metal ones because they were better able to survive fire and bomb-blast. A sad sign of popular mobilisation under local control was the death of George Marks, the town clerk and Civil Defence Controller for Canterbury. He was off duty on the night of the raid but had made an abortive bid to reach his main control room while it was going on. Driven back inside his house by near-misses, he was buried under its ruins when it took a direct hit burying him and his wife under the rubble. On hearing the sirens sound the all-clear, he said to his wife: “I wonder how soon they will come and dig us out?” The rescuers found his wife alive but came too late for Marks who had already died of his injuries.

The best eye-witness account of the raid was written by Catherine Williamson, who had played a central role in making sure that the city was as ready as it could be for an air attack when she served as mayor of Canterbury between 1938 and 1940, and was the chairman of the council’s four-person Emergency Committee.

By origin a Quaker born in Ireland, she had married a wealthy and influential local businessman. She was an unusual figure to be mayor of the highly conservative little city, but even her critics admitted she was highly energetic and a good organiser, as well as being convinced that war was coming and Canterbury was likely to be in the frontline. She had, in fact, ceased to be mayor at the time of the Baedeker raid of 1942 because she had been traumatised by bombs exploding close to her in September 1940 when there was a small-scale raid on Canterbury during the Battle of Britain. She had been out looking for a new site for a bomb shelter at the time, local residents having objected to the original proposed location. “I remember nothing but bits of masonry falling upon my tin hat: an extraordinary smell and a rush of air,” she was to recall in a fascinating post-war memoir called Though the Streets Burn, published in 1949 and long out of print.

After a prolonged convalescence in Somerset, Williamson had returned to Canterbury on the evening of 31 May, a few hours before German bombers appeared overhead. She and her successor as mayor, who had taken her place on the Emergency Committee, had realised that Canterbury as one of Britain’s most historic cities would almost inevitably be a target of the Baedeker raids that had already hit similar cities.

On each occasion, a special group of between 30 and 40 German aircraft had dropped a mixture of incendiaries and high explosives. Williamson records how she saw through a window the first few German planes circling overhead as they dropped “chandelier” flares at 12.45am that “hung in the sky over the whole area of the city and I knew that we must be prepared for the worst”. She, along with the family she was temporarily staying with, stayed at first in a downstairs room which had been especially strengthened with extra joists, but, as the bombing intensified, they went outside to go to the underground shelter. As she opened the door, she became “aware that a great part of the city was already on fire” and “a regular procession” of German bombers was arriving overhead. This went on until the raid ended at about 2.10am.

Emerging from the underground shelter, Williamson says it looked at first as if flames had enveloped the whole city. She could not even see Bell Harry, the main bell tower of the cathedral and, when there was a more than usually loud crash of falling masonry, she thought the tower must have collapsed. Despite much of the east part of the city being on fire, she made her way past blazing buildings to the control room where the staff were in a state of consternation because they had heard George Marks, the controller, was trapped in the wreckage of his house. They did not yet know that he was dead.

During the Covid-19 epidemic, an overcentralised approach goes a long way towards explaining the mistakes that have been made at every turn

Williamson had been designated to set up an information centre in a nearby part of the city where she led a team to answer pressing questions from surviving bomb victims such as “Where were they to get extra clothes? How could they get travel vouchers? Where should they claim war damage? What would they do in order to get fresh accommodation?”

Authoritative answers were given to these questions within hours of the last German bomber departing. Williamson and her team gave out £10 or £15 – worth far more at that time – in cash without inquiry from the Lord Mayor’s Fund so people could buy clothes or have the money to go to stay with relatives. The efficiency and practicality of the arrangements are strikingly different from the cryptic websites, ill-informed call centres or, for the most part, unresponsive health service institutions that were meant to do the same job during the Covid-19 epidemic.

This close-meshed civil defence organisation was not easy to establish and faced criticism from the beginning as an unnecessary waste of money. Paradoxically, the best and most detailed description of it comes from just such a critic, in this case a hostile journalist from The Daily Mail. In a heavily researched article of great length published in October 1939, a month after the declaration of war, he attacks the large sums of money spent by Canterbury on the ARP and a multitude of other civil defence organisations. The headline announces that “The Daily Mail investigates the Bomb Budget of Canterbury”, claiming that the cathedral city was “considered by defence experts to be one of the safest cities in the country”.

The writer considers it outrageous that the ARP wage bill totalled £600 a week to pay 207 defence workers to protect a “safe” city, and says that the inhabitants of the city had goggled at the amount of money being spent (though it was ultimately paid by the government). He remarks dismissively that the crypt of the Cathedral had been converted into “an ARP shelter – and there’s an awful lot of trouble about that, incidentally”. He might have added but does not that the medieval glass has been taken out the windows for safekeeping elsewhere and the nave filled with sandbags.

In accordance with government orders so they could make quick decisions, they were given tremendous powers… But a lot of people here say that the town is virtually under a dictatorship

The reporter explains that this excessive expenditure is the work of a hush-hush Emergency Committee made up of four people appointed by the Canterbury city council. He admits that the Emergency Committee and the council had acted in accordance with government orders “so they could make quick decisions. They were given tremendous powers… But a lot of people here say that the town is virtually under a dictatorship”. He notes that the chairman of the Emergency Committee is the mayor, Catherine Williamson, who he admits “works with tremendous zest and is intensely devoted to the city, but ruled the council with a rod of iron”.

A fascinating aspect of the splenetic Daily Mail article is that it unintentionally pays tribute to the complex civil defence organisation, which it derides as an expensive luxury, but which was to help save the city and its people less than two years later. It wonders, for instance, why there are so many ARP wardens, auxiliary firemen, messengers, members of light and heavy rescue parties, ambulancemen. And if this was not enough, it found that the Home Office had approved the construction of shelters “in basements and in trenches for nearly 3,500 persons”. Some 1,563 evacuees had been received in the city, some of them blind or deaf and dumb but, adds the author sarcastically, “the City has done fine work in finding them a comfortable refuge”.

The irony of this criticism jumps off the page today since we know just how wrong the writer of the piece was proved to be. But there is one aspect of his comments that is peculiarly relevant to present circumstances. “Canterbury has been given lavish powers to make itself safe,” he says. “The government has delegated these powers.” The implication is that it should have done no such thing but kept decision-making and control of spending away from spendthrift local authorities and safe in the hands of central government.

This latter prescription is certainly what has happened during the Covid-19 epidemic, an overcentralised approach that goes a long way towards explaining the mistakes that have been made at every turn. Local government, which had already seen its budgets slashed in half over the past decade, but had experience in dealing with past epidemics like polio, TB, syphilis and HIV, found itself marginalised or ignored.

Their public health organisations had likewise been starved of money and resources and were a shadow of their former selves. Many experts protested at the disaster-prone campaign of government to try to contain and suppress the epidemic using a relentlessly top-down approach. Commercial companies such as Serco have been given contracts to provide personnel in call centres to carry out the crucial “find, test and trace” effort to identify and isolate those infected with Covid-19.

Allyson Pollock, professor of public health at Queen Mary University, says that local authorities “understand and know their populations better than Serco”. Professor Anthony Costello of the University College London Institute for Global Health says that “mobilising communities is fundamental”. Germany was locked down for six weeks and has had only 8,900 Covid fatalities – less than a quarter of the number of dead in Britain, though it has a smaller population. German specialists point at one cause of their success which is a well-resourced regionalised system of government with local health authorities that can act swiftly and effectively against each outbreak as it occurs. What German towns and cities did in 2020 sounds a lot like what happened in Canterbury 80 years ago.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments