We have talent so why can’t Britain create a Zuckerberg or a Jobs?

When it comes to start-ups, Britain isn’t a patch on America, or even Ireland for that matter, says Steven Cutts

For some people in our society, the economy is a fixed thing. It’s there, it’s always been there and it isn’t going to go anywhere in a hurry. In a place such as Switzerland, people debate how to use the mountains, not how to create them. The mountains are there and it took no effort to create them. This was very much our attitude to the manufacturing industry in post-war Britain, so much so that we often described ourselves as a developed country. As if an end point called development had already been reached and the future was about something else.

But this is misleading. Industry is forever in flux. Companies are born, they live and – in the end - they all die. Just a few years ago, an apparently secure blue-chip company called Kodak filed for bankruptcy. In a time of rapid technological change, Kodak was slow to adapt and ultimately that same hesitancy would ultimately prove its nemesis.

If we look at medical imaging in the 20th century, it’s always been a source of frustration to many a patriotic scientist that we failed to discover x-rays. That honour went to the German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen, who discovered them by accident. Many people in this country were playing with x-rays at the time, but the x-rays themselves were invisible. Beyond plain x-rays, all three of the other major imaging modalities were developed partly or even completely within the United Kingdom.

Researchers in the UK played a leading role in the development of CT and MRI scanners, with both devices leading to the Nobel Prize for the workers involved. And much of the early work on ultrasound was done in Glasgow. Had the people in Glasgow managed to obtain 1 per cent of the global revenues for ultrasound, they would have raised enough money to run the whole of Glasgow University. They didn’t. For a while, some of the first CT scanners were manufactured in the UK but in the course of time, the patents were sold to an American rival and – having invented CT scanning themselves – we now import all of the CT scanners in the country. They had it, they held it in their hands, and they went on to lose it completely.

Jamie Urquhart was an engineer involved in the creation of ARM, one of the few home-grown British-based start-ups that can be reasonably compared to their American rivals. In part, at least, ARM can be seen in the context of a cluster of the hi-tech start-ups in and around Cambridge University. For many, the Cambridge cluster it is the closest thing we have to possibly rival Silicon Valley.

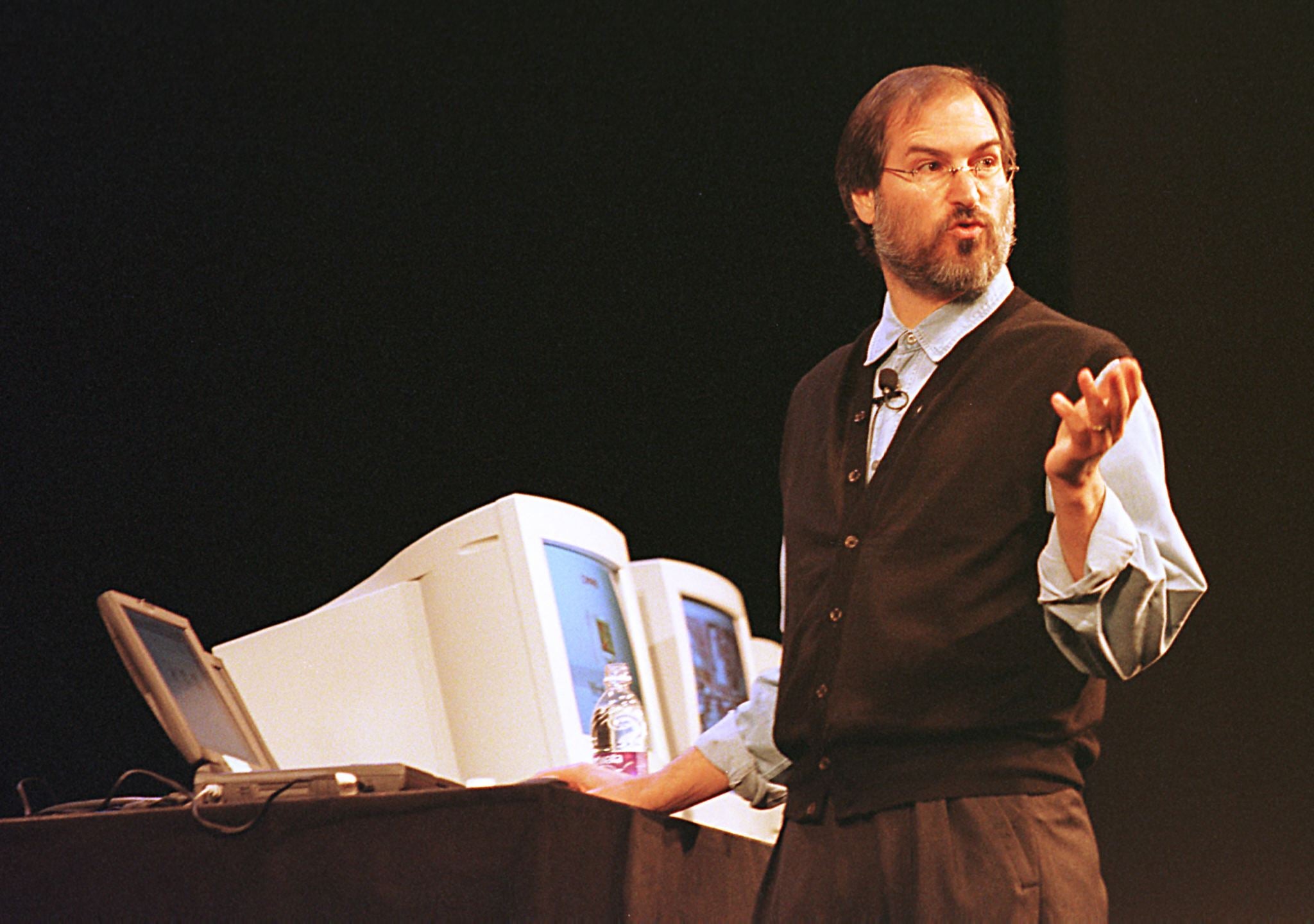

Urquhart is depressingly open about some of our failures. “Steve Jobs was incredibly focused. A lot of our tech entrepreneurs are university academics. They take an idea so far and then let it go so they can get back to their academic career. In a way, we just lack the American ambition.”

Urquhart tells me that at one stage “ARM had a higher market capitalisation than British Airways, which seemed absurd to us”. The tech industry is like that. We might say the same of Tesla and quite a few other forward-looking companies on this planet. At least some of the investors in these entities will surely come a cropper in the next few years.

It’s important to remember that ARM doesn’t build any hardware but it does design the layout of a microprocessor. Theirs is a high-skill, high-value product and its reputation on the global stage is not insubstantial. After many years of growth and development, the company was sold to the Japanese hi-tech investment group, Softbank, for a staggering $30bn. At the time of writing, Softbank is attempting to sell it on to an even larger organisation.

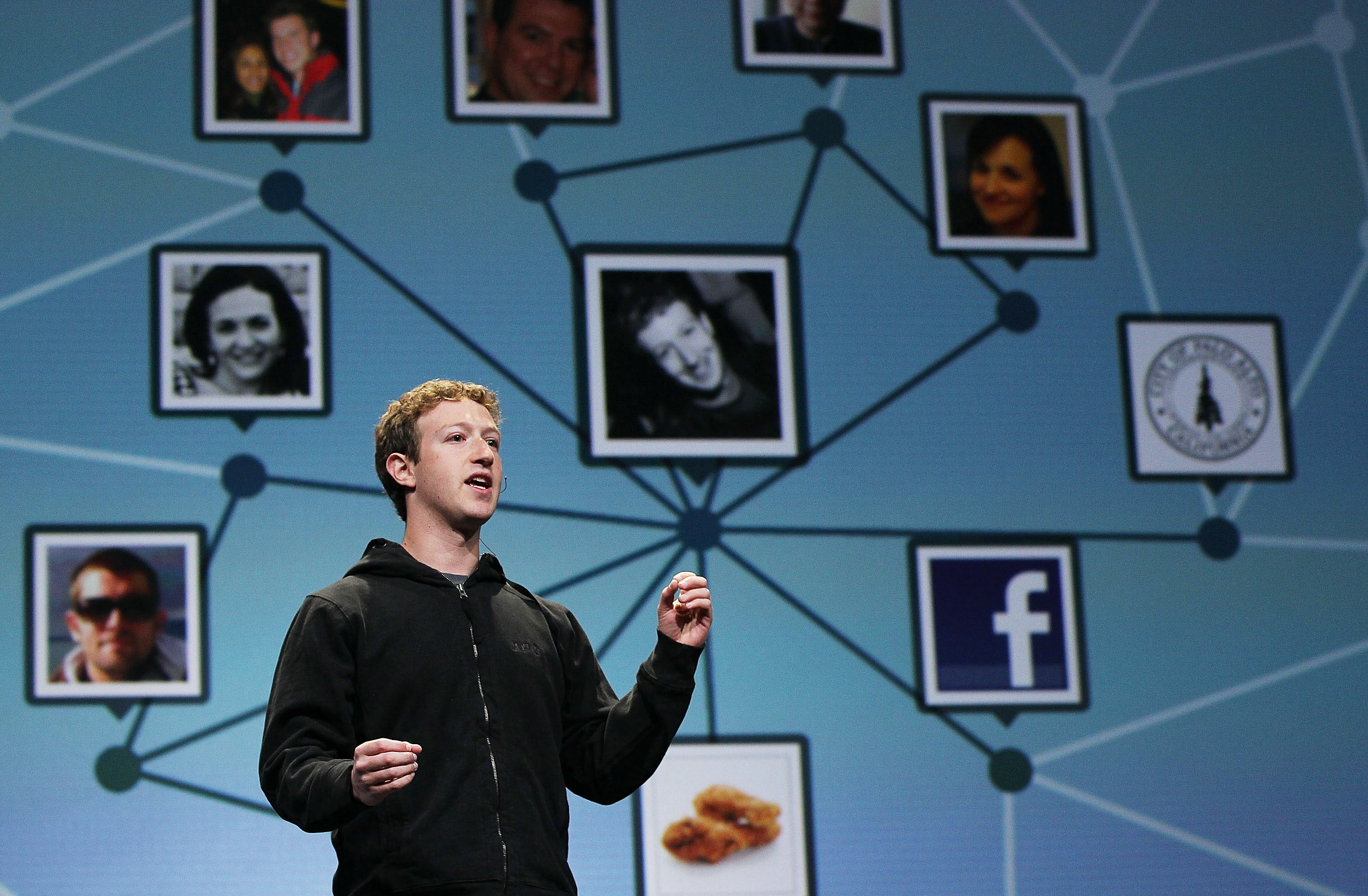

There are some in the UK tech sector who saw this as a failure. Better – they argue – for ARM to remain in British hands and continue to expand within this country. The going rate for a hi-tech success in the United States is best measured in hundreds of billions of dollars. Mark Zuckerberg famously established Facebook as an undergraduate at Harvard. Now he has a major stake in a $500bn company. He is not yet 40 years old.

Had Britain been able to throw up just one man of this ilk, the economic credibility of our entire country would have been significantly improved. It could not, although there’s never been any shortage of people calling out for the benefits that would stem from a success on this scale. When we stop to ask ourselves why this is, it’s important to remember that we had plenty of people in Britain who were at least as smart as Steve Jobs or Mark Zuckerberg. The problem is that these people just wouldn’t get off their butts and do anything.

The bottom line is that it would have been extremely good for Britain if we had developed our own version of Apple. We didn’t

But the Zuckerberg option isn’t the only way to win. Even if we couldn’t manage one Mark Zuckerberg out of 67 million people we ought to have been able to produce at least 200 men with a Dyson-level of success. The impact on our trade deficit alone would have been fantastic. Again, those of us who could have done it did not.

Or maybe it’s something else. Some authorities would look at it in terms of the seed and soil model. Maybe – just maybe – we had the seed corn on standby but the soil we tried to plant the stuff in was never going to see it thrive. If you look at a much sought after crop like the opium poppy, it turns out that Afghanistan is one of the few places on the planet with the exact temperature, humidity and sunlight intensity where this plant can flourish. If you try to grow this stuff in your back garden in Scunthorpe you won’t get very far.

That isn’t to say we never tried. Inmos was a British attempt to design and build microprocessor chips within our own borders. The soil in question was mostly Welsh and the seed corn came directly from the British taxpayer. After some early successes, the project began to falter and now – for all practical intents and purposes – it no longer exists. I cited the Inmos example to Urquhart, who agrees that the company failed but points out that there is an ongoing legacy for the British economy from the Inmos experience.

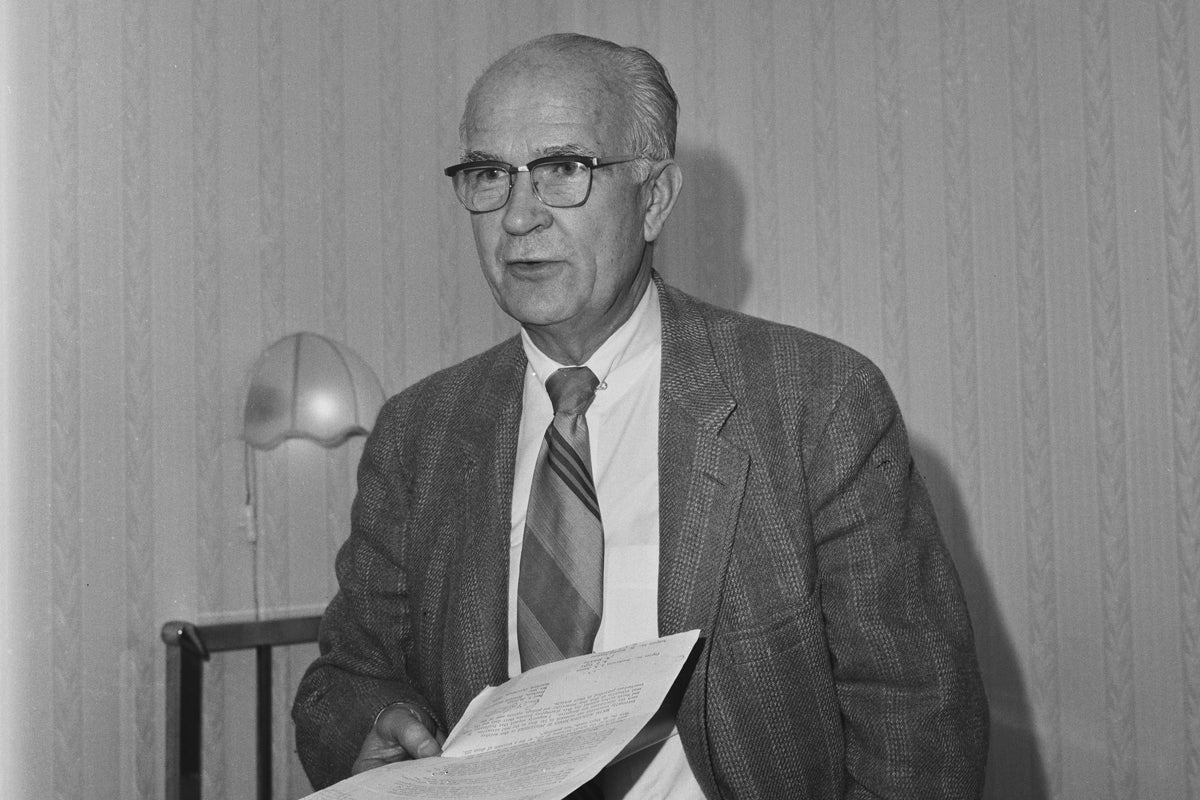

In fact, the concept of legacy is an important component of modern tech innovation. The Shockley Eight was a group of innovators which worked with legendary American physicist William Shockley in the 1950s. Having made fantastic progress together at Fairchild, they eventually decided they couldn’t cope with Shockley anymore.

Shockley was an innovator, a Nobel prize winner and, by all accounts, a difficult personality to work with. The so-called traitorous eight deserted Shockley to found their own hi-tech start-ups and – in the course of time – each of these companies would go on to disseminate their ideas and personnel into yet more start-ups. By some criteria, almost half of the companies in Silicon Valley can trace their lineage back to the Shockley Eight.

Some analysts would claim to be able to see a similar pattern in this country, albeit on a much smaller scale. In its heyday, Acorn Computers was an innovative British start-up that managed to get ahead of its competitors by persuading the BBC to use its product for a computer education show. Acorn Computers may be dead and buried, but its influence is still palpable to this day.

At a time when the UK was technically falling behind its competitors, home-grown companies such as Sinclair and Acorn Computers began to make a profound impact on the young. An entire generation of adolescents was challenged like never before and the legacy of that era is still out there, in companies such as ARM and many others too.

But at the end of the day, it’s all small-time stuff. The bottom line is that it would have been extremely good for Britain if we had developed our own version of Apple. We didn’t. In fact, we don’t have a British version of Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, Google or Twitter either. Britain’s failure to succeed in the full spectrum of these new and critically important fields might be regarded as depressing in itself but it becomes even more extreme when one considers that a similar situation has afflicted all of our European competitors. At the time of writing, not one European company is even attempting to compete with the Americans at their level. Our own leaders like to wave the flags and get excited if they can manage to persuade Facebook to rent a single office block in our capital city.

We couldn’t plant our own seeds in our own soil but at least we can offer the Americans a few acres of derelict land in London and if they do well there, a second or third multi-national might do the same.

I can’t help but feel that it didn’t have to be this way.

After Urquhart, I spoke to a financial expert in Brooklyn. Having been born and bred in the Soviet Union, she has little in the way of emotional investment in the US and, in that sense, her opinions on the US start-up culture might be seen as objective, her opinion being: “There is no question that the Americans have got something that we haven’t.”

Which is something I didn’t need to be told. European commentators are so used to lampooning the US that they struggle to come to terms with the fact that there are a number of areas in which American success is so extreme that it beggars belief.

As a child, I grew up in the days of President Reagan and witnessed – first hand – an entire sub-culture that sprung up to portray Reagan as a mindless buffoon. Almost every news item I ever saw about Reagan seemed to conclude that he was an idiot, a catastrophe for the American people. But this was misleading. Reagan governed for two terms and managed to expand national output by an additional 30 per cent. The increase in each term was greater than the entire national output of the United Kingdom.

Some of the issues here are cultural. My parents could be described as ambitious: they brought me up to achieve highly within the system. It’s important to understand that achievement and waiting to be noticed is not the same thing as entrepreneurial success. Come to think about it, I can’t remember the word entrepreneur ever being mentioned during my teenage years.

In the US, entrepreneurship is on the curriculum and entrepreneurs are celebrated. In the UK, they’d be more likely to read you a passage about social justice. Our children are taught that things should be done for them and if they are not done then we should be inclined to protest. For many people, the very idea of promoting entrepreneurship is seen as disturbing.

Investors back a whole series of companies in the hope that most will fail but at least one will break through, defying expectations

Later in my life, as an undergraduate at an elite institution, I noticed something else. The academic community, in particular, believed it should be funded from above. Initiative on their own part would never be required.

This kind of thing can permeate an entire society and alter how the people in it chose to behave. When I was a medical student, a group of doctors and technicians at a London teaching hospital built themselves a monitoring system for patients on ITU. The system was built using a few BBC Micros and bits of kit they had found in the RS Components catalogue. It worked, I was impressed, and it cost them less than 10 per cent of the going rate for the equivalent system from the mainstream companies.

As a medical student in bewildered awe I remember thinking it looked pretty hi-tech.

The consultants were so proud of their creation that they offered to build some similar systems all over London so that other ITU departments could gain the same advantage. In the end, the Siemens rep turned up and asked them to stop. So they did. Doubtless they said something apologetic and then he took them out to lunch.

Medical devices are notoriously over priced: you can bet your life that much of this kit could be created for a fraction of what we’re paying today but there simply isn’t the will to challenge the market leaders.

This sort of thing is also a manifestation of something else: culture. At times, Britain seems to lack a culture of personal initiative and innovation. Risk taking is openly frowned upon and success is widely disdained. In many circles, there is a widespread expectation that the future would be a linear extrapolation of the past. All of us are a product of that culture and in any society it is difficult for any one man to step outside the box and do things differently.

At Imperial College, Doctor Ruddock (then husband of the CND campaigner Joan) told me that most IC graduates would spend their lives being subservient to people who are – intellectually – their inferior. There’s more than a bit of truth to this and it raises the question of why the cleverest of people don’t work for themselves.

Exactly how the Americans are doing it is hard to understand. Others focus on the famously eager American banks that are willing to lend a seven-figure sum to a start-up company and not even bother to blink when the start-ups fold. Better than that, when the same people come back and ask for a new loan to start a second company, the banks says yes!

Failure is after all an important part of the learning curve for any man. Well, maybe, yes in a few select cases where specialist bankers have examined the previous project in tremendous detail and judged the culprits to be guilt free, yes, they’d rather bet money on people with experience than a complete beginner. Even accounting for such profligacy, the vast majority of hi-tech start-ups fail and in effect, the investors back a whole series of companies in the hope that most will fail but at least one will break through, defying expectations and bringing some fabulous return on their investment.

It’s important to remember that not all start-ups rely on banks. Some of them obtain money from wealthy individuals who expect a significant fraction of the eventual profits and equity if the company becomes successful. In the 1970s, Mike Markkula was the first significant investor in Apple and only its third employee. For a layout of around $250,000, he managed to bring home a stake that is best measured in billions. Needless to say, your average Angel Investor isn’t quite so lucky as Mike. Like it says in the ad: “The value of your investment may go up as well as down.”

Another focus of popular debate is the Corporate Tax rate. Some years ago, the Irish went for 12 per cent and are still convinced that this is why they have managed to attract so much overseas investment. Recent attempts by the Biden administration to force Ireland to increase its corporate tax rate to 15 per cent have caused genuine alarm in Dublin.

But this is misleading. In reality, the Irish have merely reduced overall operating costs in the eyes of the investor and might as well have cut their average wages and retained a more mainstream rate of corporate tax. There are people in this country who think we should try to emulate them and call that a substitute for a tech/economic strategy.

Britain has more than 11 times the population of the emerald isle and we ought to do better – and we ought to be better at the creation of wealth through business start-ups. The government should be seen as the cultural equivalent of the fictional Miss Bennet. She accepts that none of her daughters will ever be able to do anything in life but sees correctly that there are men like Mr Darcy out there. All she has to do is to persuade Mr Darcy to take an interest and Elizabeth Bennet’s future is assured.

Like many of the core driving forces in the modern world, it is an idea that stems from America.

Finally, there is some light at the end of the start-up tunnel. There has been a surge in some sectors, especially during lockdown, which speaks to a degree of creativity and entrepreneurial spirit. But our inability to grow our own young companies on an American scale remains a source of frustration.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments