What do Trump, Farage and Hitler have in common? A reliance on fiery, antagonistic rhetoric

Victor Klemperer’s moving diaries about the Second World War are of huge historic importance. But the volume he valued most is a short and devastating treatise on the linguistics of the Nazi regime, a lingua franca the far right continues to recycle to this day, says Robert Fisk

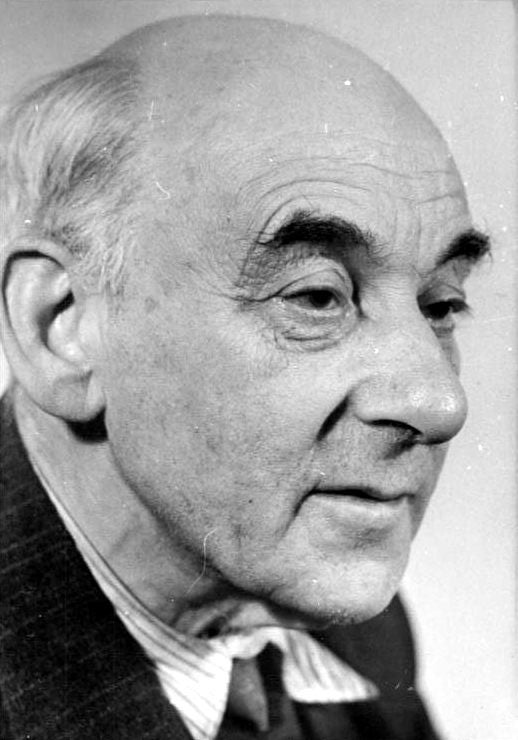

Victor Klemperer was perhaps the most eloquent and academically brilliant survivor of the Holocaust. He was never sent to Auschwitz – although he was only hours away from that fate in February 1945 when the Allied bombing of Dresden allowed him to dispose of his Jewish Star – but as a philosopher, French scholar, professor, linguist and humanist, he wrote by far the most moving diaries of the Second World War.

Scarcely days pass when I do not think of Klemperer. His three volumes of diaries are a testimony to viciousness, cruelty and courage from the heart of darkness, trying (and just succeeding) to survive as a German Jew in Hitler’s Reich. But only now have I been able to obtain a translation of the one volume this fine Jewish intellectual valued most: his own short, devastating treatise on the linguistics of the Nazi regime.

He called it LTI – short for his Latin title, Lingua Tertii Imperii, The Language of the Third Reich – and it hangs like a cloak over us today, in the shadow of the new right, of east European nationalism, of racism and I suppose, of Trumpism too. And of the crisis of dictatorship in the Middle East. It shows how language can be used as a prison rather than a means to liberty, how it can wrap us in chains when we always thought it offered a path to freedom. “Nazism,” he wrote, “permeated the flesh and blood of the people through single words, idioms and sentence structures imposed on them in a million repetitions and taken on board mechanically and unconsciously.”

We hear a lot about Palestine now. It does not appeal to us. Anyone who goes there exchanges nationalism and narrowness for nationalism and narrowness

It is always dangerous to pour our present perils into the matrix of the past, to pretend that we can interpret all our current ills through the light – or perhaps I should say darkness – of that particularly unique and terrible period of European life and death which existed between 1933 and 1945. But Klemperer, a cousin of the great conductor Otto, was a peculiarly contemporary figure.

He could see the bathos and stupidity and even unconscious humour of Nazism – and that indeed takes a brave man – as well as the foolishness of humankind outside the terrors of the age. Like Anne Frank, his German contemporary in Amsterdam, Klemperer’s diary is of the greatest historical importance. Unlike Anne, he survived – to become a professor in communist East Germany.

Yet very early on in the Nazi regime, he was opposed to Jewish immigration to Palestine. “We hear a lot about Palestine now,” he wrote in Dresden in July 1933. “It does not appeal to us. Anyone who goes there exchanges nationalism and narrowness for nationalism and narrowness. It is about the size of the province of east Prussia; inhabitants: 200,000 Jews and 800,000 Arabs.”

The following year, Klemperer is musing on the plight of an Aryan German girl who has fallen in love with a German Jew who has already travelled to Palestine (and thus, of course, safety from the Nazis). “But where are they to get married? He must travel to meet her somewhere, where that is possible. Because in Zion the Aryan is exactly in the position of the Jew here. ‘Par nobile fratrum’!”

Indeed, Klemperer goes on to make some terrifying parallels between Zionism and the “winding back of the world” in the search for “cultural roots” which National Socialism was encouraging in Germany, at the same time as Zionists “who want to go back to the Jewish state of AD70 (destruction of Jerusalem by Titus)…” Klemperer refers to the “naive stories” of Zionism. He is not comparing a future Israel to Nazi Germany – at least, we must hope so – but this is not bedtime reading for Benjamin Netanyahu.

By 1943, Klemperer’s anti-Zionism is becoming less pronounced, discussing the modern Hebrew introduced to Jewish areas of Palestine (“an artificial mixture of European and American elements with ancient Jewish ones”) with comparative equanimity. If he is less critical of the “new” Palestine now, it is not without reason. This was at a time when his diary also records how “in the Munchner Platz, there is an electrically powered guillotine, a head every two minutes; not just Jewish ones; the main killing time is 6pm, often as many as 25 heads fall one after the other...”

And it is around now that Klemperer hears an argument that many today must have heard – of immigrants, of Muslims, and which I even heard recently of Armenian victims of the 1915 genocide. Klemperer records a German Jewish friend lamenting at a remark he overhears: “But your husband must have done something wrong; they don’t just kill someone for no reason!”

The contemporaneous nature of the Klemperer diaries emerges in the post-war period when a friend leaves Israel because of “atrocities” committed against Arabs. “The Israelis have American masters and American blades in their claws,” he laments in 1955. “The Egyptians are ‘looked after’ by the Russians. I cannot say what an aversion I have to politics and how repugnant to me both sides are.”

What the little people did, what the ordinary people did, what the people who have been oppressed over the last few years did, they rejected the multinationals, they rejected the merchant banks

But back to LTI, the linguist’s handbook to Nazi Germany. There is much for our Europe today in Klemperer’s words, not directly in the facile way of which I warned, but simply by listening to his warning and thinking of the ill-educated words of contemporary European politicians, even of the Brexit debate (if it could be rewarded with the word “debate”). Here, for example, is Klemperer on just one aspect of antisemitism:

“One might ask whether this endless assertion of Jewish malice and inferiority, and the claim that the Jews were the sole enemy, did not in the end dull the mind and provoke contradiction…” Hitler preached “not only that the masses are stupid, but also that they need to be kept that way and intimidated into not thinking. One of the main means of doing this is to hammer home incessantly the same simplistic lessons, ones which cannot be contradicted from any angle. And think how many threads there are connecting the soul of the (invariably isolated) intellectual to the masses that surround him!”

And Klemperer tells the story of an apparently pleasant, well educated Lithuanian girl in whose company he found himself while fleeing Dresden. “I never liked his [Hitler’s] attitude towards other nations,” the girl told Klemperer. “My grandmother is Lithuanian, why should she, why should I be any less worthy than some pure German woman ... Yes their [Nazi] entire doctrine is based on purity of blood, on the Teutonic privilege, on antisemitism ... In the case of the Jews he may well be right, that’s a somewhat different case ... I’ve always avoided them ... You hear and read such a lot about them.” Klemperer, truly stunned, writes that “I tried to think of an answer which would combine caution and enlightenment.” The girl would have been 13 when Hitler came to power in 1933.

There are other times in this small volume when – to use an expression my mother would employ whenever she shuddered – someone steps on my grave. In 1933, Klemperer writes, he went to the cinema and saw Hitler in a newsreel with a sound film sequence: “The Fuhrer says a few words to a large gathering. He clenches his fists, he contorts his face, it is more a wild scream than a speech, an outburst of rage: ‘On 30 January they (Hitler means the Jews of course) laughed at me – that smile will be wiped off their faces!’”In 1942, almost consciously picking up on these earlier words, Hitler remarked of the Jews that they once laughed at his prophecies. “I don’t know whether they are still laughing…but I can assure you that everywhere they will stop laughing.”

And I think – and no, the man of whom I speak is not a Hitler, not a Nazi, not an antisemite – of another speech, in Brussels in 2016, when a man told the European Union that “when I came here 17 years ago and I said I wanted to lead a campaign to get Britain out of the European Union, you all laughed at me. Well, I have to say, you’re not laughing now, are you?” But I do shudder a little more when I read what Nigel Farage then said: “Because what the little people did, what the ordinary people did, what the people who have been oppressed [sic] over the last few years [did], they rejected the multinationals, they rejected the merchant banks...”

The little people, humiliated, oppressed – by bankers, for heaven’s sakes – is surely a stereotype that must be recognised. By the way, I deliberately reject the trendy expression “trope”. A stereotype is a stereotype is a stereotype. But wait. Here is Trump in 2017: “At what point does America get demeaned? At what point do they start laughing at us as a country? We want fair treatment. We don’t want other leaders and other countries laughing at us anymore, and they won’t be.”

Like thousands of other Jews in Germany, of course, Klemperer, who fought for his country in the 1914-1918 war, could not at first believe he might be in danger. Thus he regarded German Zionism – even Theodore Herzl – as eccentric and exotic rather than politically important to Jewry. “What did it have to do with the world in which I moved, and with me personally? I was so confident about being a German, a European, a 20th-century man. Blood? Racial hatred? Not today, not here – at the centre of Europe! And wars weren’t to be expected any more either, not at the centre of Europe ... at most somewhere in the far reaches of the Balkans, in Asia, in Africa.”

In one sense, we are all, perhaps, living in Plato’s cave, bewitched by the shadows on the wall in front of us, unable to interpret what they represent. And that, I fear, is how we are supposed to be

All this might sound mundane were it not for the constant nationalist use of the idea that they – the little “oppressed’’ people – represented some form of popular will. Today, for example, we are very used to the Brexit language about the people of Britain, the people’s will. But translate “people’’ into the German “volk’’ and a shadow is cast over the language of Toryism. Much more important is Klemperer’s insistence that nationalism is not as important – in the creation of Nazism – as Romanticism, of national myth, of the false deployment of a national “narrative’’.

And here the Brexit “debate’’ and the UK’s departure from the European Union becomes far more relevant. Klemperer describes how Nazi writers “were keen to go around like philosophers, from time to time they were keen to direct their attention to the intellectuals; that impressed the masses ... Romanticism, not only of the kitschy kind, but also the real one, dominates the period, and the innocent and the mixers of poison, the victims and the henchmen, both draw on this same source.”

Most dictators and most populist leaders are lovers of romanticism, of the deepest and most dangerous kind. Whether their history is falsified, embellished, twisted, it is true that those who first feared nationalism in Europe identified Romanticism as its cause. In the Middle East today, most tyrants are able to draw on a library of myths and truisms and distortions or non-sequiturs to explain the immutable nature of their quarrel. What else is the Sunni-Shia conflict but a parody of Arab Muslim history?

In one sense, we are all, perhaps, living in Plato’s cave, bewitched by the shadows on the wall in front of us, unable to interpret what they represent. And that, I fear, is how we are supposed to be. Only Plato’s philosopher understands what the shadows – made by a fire behind our back – represent. But who are the philosophers now?

When Hitler moved to Vienna in 1908, it was an immigrant city. Almost nine per cent of the population would soon be Jewish – Jews from Hungary, Galicia and Bukovina. Ethnic Germans feared the foreignisation which this immigration represented; German Austrians, as historian Volker Ullrich pointed out in the first volume of his Hitler biography, feared losing their political hegemony.

Hitler buried himself in books – Germanic myths and heroic sagas, as well as Ibsen – and when the Academy of Fine Arts slammed the door in his face, the Fuhrer-to-be uttered words which must seem worryingly familiar to us today. “Nothing,” he raged, “but a bunch of cramped, old, outmoded servants of the state, clueless bureaucrats, stupid creations of the civil service.”

The Austrian Social Democrats were the second most powerful force in pre-First World War Vienna; their internationalist programme sounds not unlike that of the embryo European community. Hitler believed the Social Democrats were exploiting the hardship of the working classes. “Who are the leaders of these people living in misery?” he wanted to know. “They’re not men who have experienced the hardships of the little guy themselves, but rather ambitious, power-hungry politicians, some of whom have no idea of reality and who are getting rich off the misery of the masses.”

Now when did I last hear these words? No, history does not repeat itself. But it does sound grimly familiar.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments