Dirty money: Can the UK afford to turn down kleptocracies?

After the economic downturn brought on by coronavirus and Brexit, the UK may have no choice but to turn even more a blind eye to this influx of foreign cash, writes Tom Mayne

The recent FinCEN scandal – which saw the leak of confidential bank reports – allowed us a peek behind the curtain at the vast amounts of dubious funds that pass through our financial system. As well as moving money for fraudsters and drug dealers, the leaked files show how shady officials from corruption hotspots transfer millions from their countries through some of the world’s biggest banks. These countries are often referred to as “kleptocracies” – where the ruling elite abuse their power to make incredible fortunes from the country’s natural resources.

The transfer of dubious capital into Europe and America from kleptocracies not only deprives the people who live in these countries of much-needed revenue, but represents – in the words of Tom Burgis, the author of the recent Kleptopia: How Dirty Money is Conquering the World – “the privatisation of power itself”. The ongoing protests in Belarus highlight the close link between kleptocracy and a lack of political freedom: according to one estimate, since coming to power, president Alexander Lukashenko and his entourage have misappropriated $10bn from the Belarusian people.

But the flow of dodgy cash also has a corrosive effect on the jurisdictions where the money ends up: lawmakers’ opinions are swayed by shadowy lobbyists; paid-for articles in western media paint rosy pictures of corrupt dictatorships; house prices are distorted by the influx of illicit foreign capital (a point made in 2015 by the economic crime director of the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA) in reference to London’s sky-high property prices). It is no wonder then that London gets referred to as the money laundering capital of the world, and acts as a key hub for a whole host of “gatekeepers” – bankers, real estate agents, company service providers, PR agents, lobbyists and lawyers – that kleptocrats need to help hide their ill-gotten gains.

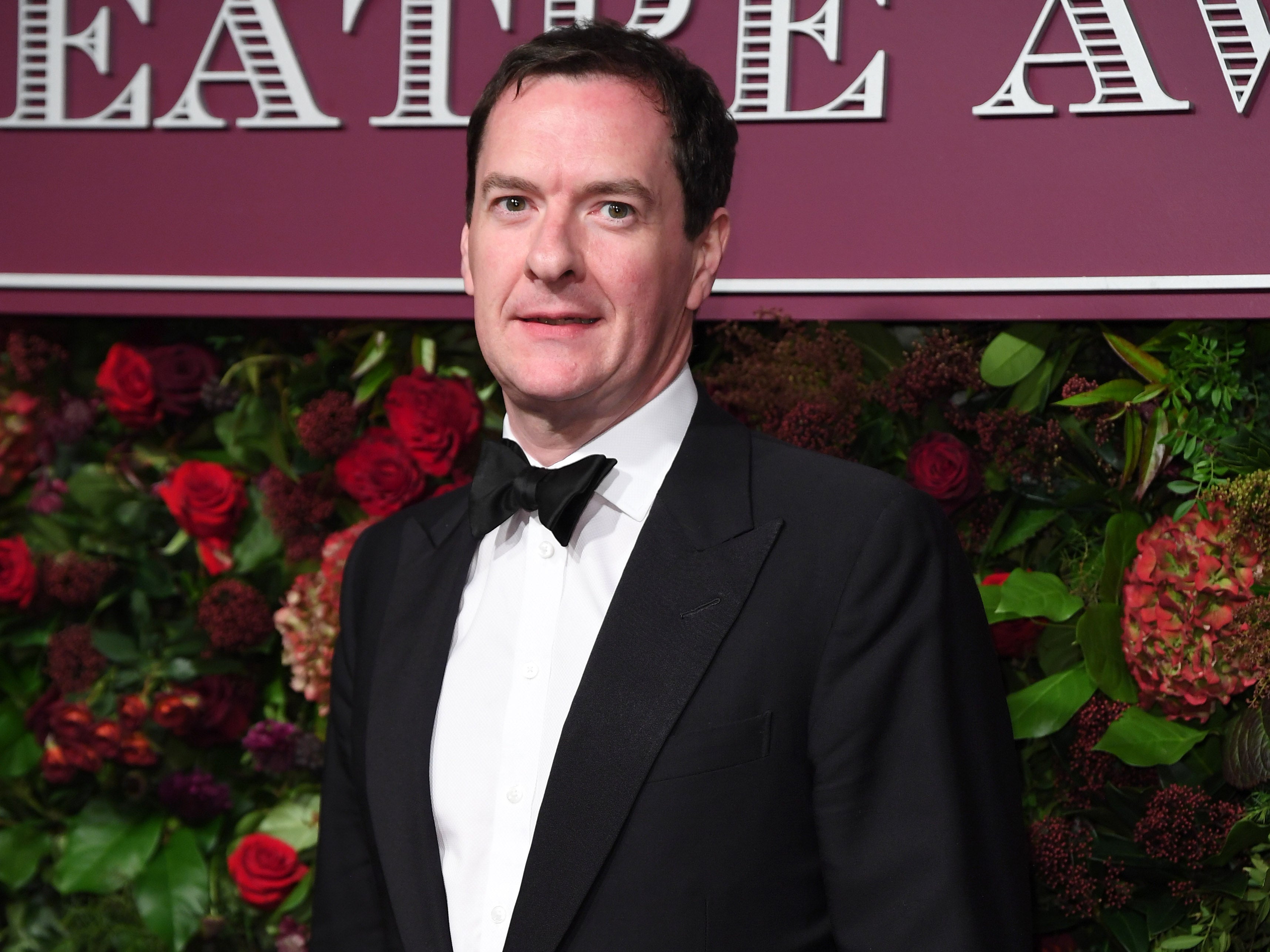

The British government claims it is committed to stamping out corruption, but in light of rather grim predictions for the future of the economy thanks to the double whammy of Covid and Brexit, we have to ask whether that commitment will continue to be taken seriously. There is the precedent of the UK being more worried about the bottom line than holding accountable those responsible for illicit financial flows: in September 2012, then chancellor George Osborne sought to influence a US investigation into money laundering allegations at HSBC, when he implied that prosecuting the bank could lead to a renewed financial crisis. A 2016 US report even claimed that the UK’s Financial Services Authority hampered the investigation into HSBC.

Government officials will point to the fact that the UK has enacted much legislation in recent years that aims to improve transparency and make it harder for the criminal and the politically exposed to hide ill-gotten gains. For example, the UK was one of the first countries in the world to implement a “beneficial ownership” register that puts on record the true owners of companies registered here. However, with Companies House hopelessly underfunded, there are very few checks on the information submitted, and nobody is prosecuted for giving false information (except, famously, one whistleblower), so the registry contains such beneficial owners as “Mr Xxx Stalin” and “Xxx Raven”. Last month the government announced it was making reforms to Companies House to clamp down on fraud, but the timeline is vague, with changes enacted “when parliamentary time allows”.

The government has also pledged to prevent the owners of UK real estate from hiding behind anonymous offshore companies with the introduction of the Registration of Overseas Entities Bill. Such legislation is needed, as investigations by NGOs have shown that investing in real estate is a method favoured by foreign officials to get their cash into the UK. When David Cameron announced the government’s intention to clamp down on corrupt foreigners investing in real estate in 2015, he cited a property portfolio owned by a figure from Kazakhstan worth around £150m.

Further investigations from 2018 suggest that the buildings, which included a massive block of offices and luxury flats located on London’s famous Baker Street, were owned by Dariga Nazarbayeva and Nurali Aliyev, the daughter and grandson of the then president of Kazakhstan. Nazarbayeva – who has held such positions in Kazakhstan as deputy prime minister and chair of the Senate – has an estimated net worth estimated of $595m. Nazarbayeva’s own lawyers claim that she established her first business in 1992 and “was one of many entrepreneurial individuals who capitalised on the economic reforms in Kazakhstan at this time. The goods were acquired under the terms of a consignment agreement and accordingly no initial capital was required.” Unfortunately for those looking to back up these claims, “significant efforts have been made in Kazakhstan to locate documents relating to this business but given the passage of time these are no longer available. However, [Nazarbayeva] estimates that she made many millions of dollars (possibly as much as $40m-$45m) during this three-year period.” No mention is made, of course, of the fact that at the time her father was the president of Kazakhstan, having won the 1991 election with 98.8 per cent of the vote.

All of Kazakhstan’s richest are either family members or political allies of Nazarbayev. His son-in-law, Timur Kulibayev – net worth $2.8bn – reportedly bought Prince Andrew’s mansion for £15m in 2007, despite the fact it was valued at £12m. It was later reported that Andrew was advised by one agent that the house was worth about only £8m on the open market and possibly as little as £6.4m at auction – under half of what Kulibayev bought it for. The site was kept derelict for eight years, before Andrew’s old house was demolished and a new, even bigger mansion constructed. It’s not even the only real estate Kulibayev owns in the UK: in 2007, he went on quite a spree, buying other properties in the UK, one of which – a mansion in Mayfair – stood empty for at least 14 years.

Kleptocracy is the norm in central Asia, yet the money still seems to find a way of reaching UK shores. Headlines regarding Uzbekistan in recent years have focused on legal proceedings against Gulnara Karimova, the daughter of Uzbekistan’s first president. In March 2019 the US Department of Justice unsealed charges against Karimova in relation to an $866m money laundering and bribery scheme. According to the charges, Karimova and her associates received the money from companies looking to acquire licences in the Uzbek telecoms business. Much of what Karimova allegedly received was ploughed into international real estate, with reports of properties in France, Switzerland and the UK. The UK’s Serious Fraud Office has frozen three of Karimova’s held in and around London, one of which, an £18m mansion in Surrey, had its own boating lake and indoor swimming pool.

In a bid to tackle dubious cash from entering the real estate market, the UK introduced the Unexplained Wealth Order (UWO), where politically exposed people or those suspected of being involved in serious crime are required to explain the sources of wealth used to buy UK property, else risk having it frozen. The outcome of the two UWOs issued so far on politically exposed people provides a stark contrast. The first concerned two properties worth a combined £22m that belonged to Zamira Hajiyeva, the wife of a now-jailed banker from Azerbaijan. Hajiyeva spent over £16m over a 10-year period in Harrods, including £32,000 in one day just on chocolates. The case against Hajiyeva was relatively straightforward as she could not come up with much evidence to suggest that her husband’s wealth was legitimate, and she had no significant sources of her own. Documents pertaining to the case allowed campaigners to see how things in the world of high-end finance operate: even when Hajiyeva’s husband was found guilty in Azerbaijan on financial crime charges in October 2016, his wealth management company continued to help him manage his money, placing a house that his company had built on the market, with the listing appearing on a website 10 days after his conviction.

However, when another UWO was filed in May 2019 on three London properties worth £80m the outcome was rather different. The NCA believed they were bought by funds acquired by Rakhat Aliyev, another son-in-law of Nazarbayev, who was found dead in a cell in Austria in 2015 while awaiting trial for the murder of two bankers in Kazakhstan. The properties in fact were owned by Aliyev’s ex-wife, Dariga Nazarbayeva, and their son, Nurali Aliyev. The UWO was dismissed by the High Court after their lawyers produced enough documentation to suggest that the wealth was legitimate and unrelated to Aliyev’s crimes. The judge also took into consideration investigations, court rulings and enforcement actions in Kazakhstan. This is the same country about which the US State Department said in 2019 that “the executive branch sharply limited judicial independence” and that “impunity existed for those in positions of authority as well as for those connected to government or law enforcement officials”. In other words, no court in Kazakhstan is going to rule against the president’s family, in the same way that no court in Russia would rule against a relative of Putin. The ruling was met with dismay from anti-corruption campaigners. Peter Zalmayev of the Eurasia Democracy Initiative said: “It is disappointing that the judge did not take into account the total monopoly of wealth in Kazakhstan held by the family of Nazarbayev and his associates, a monopoly that allowed Dariga and Nurali to accrue such wealth unfairly in the first place.” The UWO failure in this instance sets a grim precedent as it suggests that UWOs directed at well-heeled foreign officials will only be effective when these individuals no longer enjoy the protection of their own state apparatus.

Where does that leave UK enforcement actions? It is clear that banks are the first line of defence when it comes to stopping the outflow of corrupt funds. Unsurprisingly, Kazakhstan features prominently in the FinCEN files: banks allegedly transferred a total of $89m for the family of Viktor Khrapunov, the ex-mayor of Kazakhstan’s largest city, Almaty, with money transferred even after Interpol issued a Red Notice for his arrest. Even worse, it is claimed that between 2008 and 2016 an incredible $666m was transferred to accounts linked to Mukhtar Ablyazov, a Kazakh banker accused of massive fraud. In 2009, a British judge froze his assets, and between November 2012 and March 2013, British courts passed over $4bn in judgments against him, yet the money continued to flow. Khrapunov and Ablyazov claim the charges are politically motivated after both men fell out with Kazakhstan’s leadership.

The banks will argue that they did what they were supposed to: flag the transactions (dubbed Suspicious Activity Reports, or SARs) to FinCEN, which has the ability to investigate and freeze the funds. However, there is growing evidence to suggest that such supervision fails to stop the majority of money laundering. In the UK, SARs are sent to the Financial Intelligence Unit of the NCA. Regulated industries such as banks are legally obliged to report a transaction if there is a suspicion or knowledge of money laundering.

While this sounds good in theory, it leads to “defensive” reporting – where banks try to avoid legal liability by issuing SARs. In 2019, the NCA received around 478,400 SARs, over 80 per cent of which were sent by banks. The NCA simply does not have the capacity to investigate hundreds of thousands of reports, meaning that serious instances of laundering can slip through the net. Of course, banks could simply refuse to authorise the transactions, but the FinCEN scandal suggests that banks are happy to let the money pass and earn ample fees, while using SARs to “inoculate” themselves against legal liability. Such a system allows kleptocrats to flourish, as they thrive off the fact that their grey schemes are escaping scrutiny. Meanwhile, SARs issued from other sectors remain low: in the UK, 635 were filed from real estate agents and just 23 from trust and company service providers. In acknowledgement that the system is not working, the British government’s 2019-22 Economic Crime Plan includes as a commitment to reform the SARs regime as a key deliverable.

It remains a criminal offence if you work in a regulated industry and fail to file a SAR when you have a suspicion or knowledge of money laundering. Yet prosecutions are low: only three have been reported across all regulated sectors – banks, stock brokers, insurance companies, accountants, tax advisers, estate agents, company service providers, auctioneers, casinos, legal practitioners – since the law was introduced in 2002. Part of this is lack of enforcement, but it also points to a problem in the law itself: it is difficult to prove what constitutes a “suspicion” of money laundering, especially seeing that the term is not defined in the law.

In recent years, the freezing of funds stolen from the 1MDB fund in Malaysia has provided civil society with an example of how western law enforcement agencies can act together to help recover stolen state funds, with more than 10 countries working together to return the money and hold the perpetrators to account. Likely with this in mind, a group of Eurasian civil society organisations recently called on western governments to do more to investigate funds stolen from their home countries. Yet arguably if banks had been taking their anti-money laundering responsibilities seriously, the money would never have been transferred out of these countries in the first place. How to change this? An overhaul of the SARs system, heavier fines and sanctions for banks that break the rules, more scrutiny of the “politically exposed”, and the prosecution of those bank officials who fail to flag suspicious transactions. Will this happen? The jury is out, but with economic storm clouds gathering, it is extremely doubtful.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments