From Brexit and Covid-19 to the cost of living crisis – small businesses have had it tough

Nathaniel Cramp and his Sonic Cathedral music label have had to deal with plenty during the past few years, writes James Moore. And things aren’t getting much easier

Nathaniel “Nat” Cramp was staring at the news with horror.

A no-deal Brexit threatened the future of his small record label, Sonic Cathedral, which has played an important role in the revival of the shoegaze genre, helping some exciting young bands to release their first physical recordings and giving voice to a few old favourites too.

The label’s records are pressed in the Czech Republic and when Boris Johnson was stamping up and down making threats to the EU, no one was quite sure what trading would look like and how punitive the feared tariffs on imports and exports would be.

The Brexit “Trade and Co-operation” deal he ultimately signed was dismal. But it at least headed them off. So the Sonic Cathedral stayed in business and its bells continue to ring today. Running a small indie label is far from easy. But the congregations have proved healthy.

The future, however, is still uncertain. And Brexit is still playing a role in making it that way.

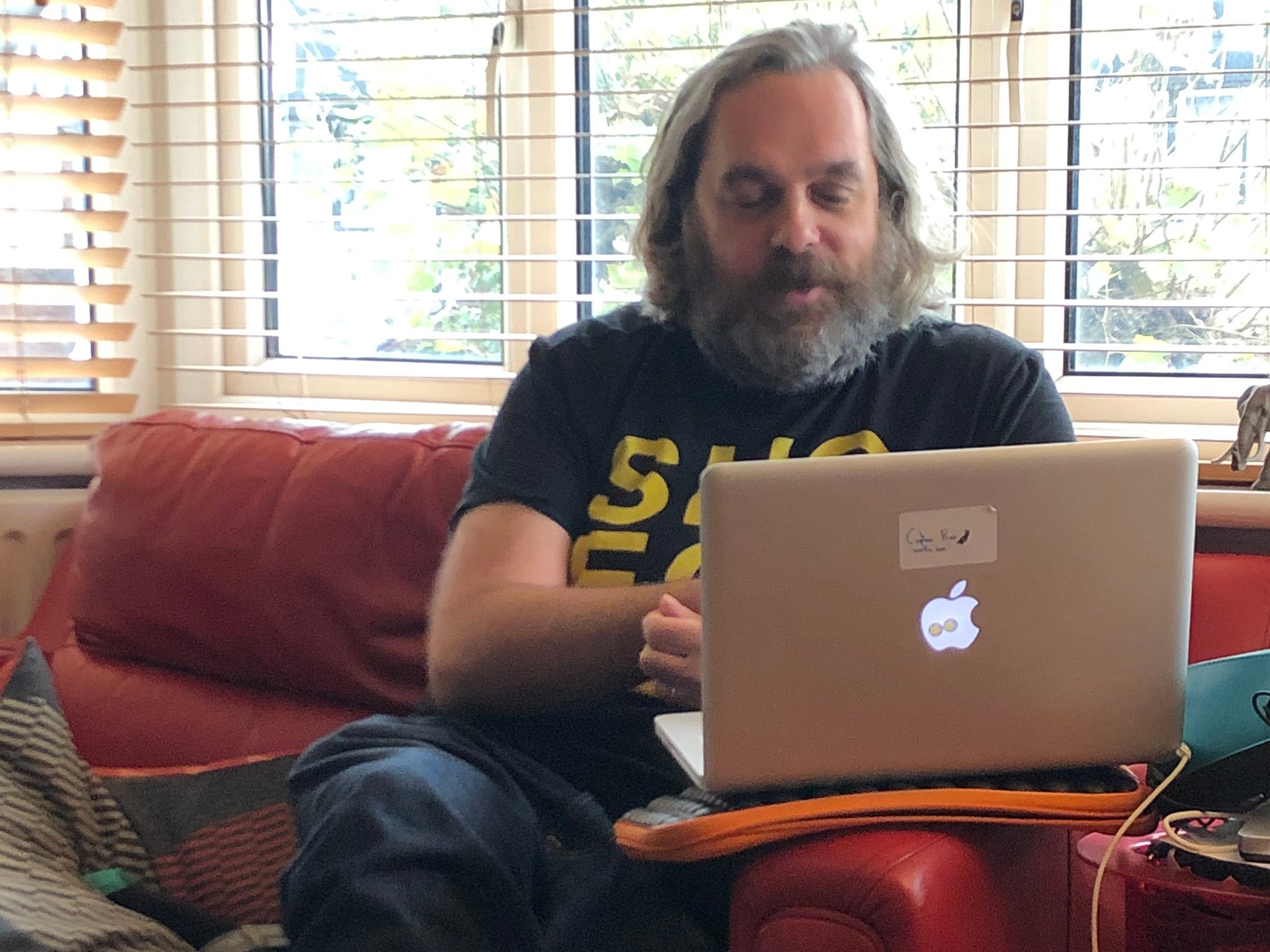

Cramp and I meet for an update at his Golders Green flat, from where he runs the business – having spoken before. He’s a big man, but softly spoken with a nice line in dry humour. Perhaps he has a few more grey hairs than last time, but that’s all.

He wears a bright yellow Horsegirl T-shirt in honour of the trio of Chicago teenagers whose first physical release – a seven-inch single – he put out. They subsequently signed to Matador, and received positive reviews for Versions of Modern Performance, an intoxicating fuzzed-up collection of songs with influences drawn from the last three decades of indie music. It’s a shoegaze classic – or perhaps that should be nu-gaze as the new generation of acts are known.

You win some, you lose some. Not that Cramp is complaining. He recently put out a banger of a double LP from Ride, then Oasis, and once again Ride guitarist Andy Bell. Bdrmm, another group of youthful nu-gazers championed by the label, are still signed to it and have been garnering plaudits of their own. They recently toured with Scottish post-rock legends Mogwai.

There is also the strange tale of Pye Corner Audio, whose hypnotic, ambient noise, somehow made it to number one in the dance charts.

“I don’t know how, or why,” says Cramp, both amused and bemused by the achievement. “You can’t dance to it. But I’m quite proud of that.”

He’s right. You absolutely can’t dance to it. But he should be proud of it and a lot more besides. Just keeping a small record label going is an achievement in the current climate.

As it turns out, the Sonic Cathedral faced a bigger challenge than navigating the Trade and Co-operation Agreement. It was the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic.

When previously we talked, Cramp had just put out a 10-inch EP. It cost the label £1,872 for 500 copies. He’s just wrapping up an almost identical release that set him back £3,240

“When we last spoke we didn’t know what was round the corner, which was Covid. I think because of that, and the Ukraine situation, everything is more confused. Brexit is one of many issues. It’s a part of a bigger global situation,” he says.

Some positives did emerge from out of the darkness of Covid: “I had a sense of foreboding when we last spoke but even though, for many reasons, 2020 was a horrible year there was a positivity that came out of it. There was a sense of community. People doing positive things. I don’t just mean the banging of the pans on a Thursday night. It was people getting behind music labels and artists and supporting them because they couldn’t tour.

“Because they weren’t going to gigs or going out or travelling to work, they were buying records. So there was a spike in sales and that was good. Last year felt like a bit of a hangover from that because it was impossible to keep that positivity going in the face of all the other issues.”

Those issues included delays to manufacturing, caused by a rash of releases including by megastars like Adele and Ed Sheeran. Revenue from vinyl overtook that of CDs in the UK for the first time since 1987 but even before Adele’s record-breaking order, capacity constraints were causing problems.

Critics have pointed out that the “blame Adele” narrative is simplistic. It wasn’t the only contributor to the bottleneck the industry experienced. But it is always the little guys, with limited pressings, that suffer the most in those circumstances.

Then along came the cost of living crisis. This is perhaps the biggest threat facing Cramp’s label.

Vinyl was a premium product before it got going. A small luxury for those who indulged. But its price has been rising sharply. When previously we talked, Cramp had just put out a 10-inch EP. It cost the label £1,872 for 500 copies. He’s just wrapping up an almost identical release that set him back £3,240.

“That’s quite an increase,” Cramp says. “Prices are going up a lot. If you look in record shops, records are going for ridiculous amounts of money. I’ve always resisted charging stupid amounts because I don't like it. I personally can’t afford to be going to Rough Trade or any other shop. You leave empty-handed because you can’t justify £40 on any record.”

Labels face more uncertainty too: “You get a quote but instead of paying the quote you’re given, it is changeable because they just don’t know how much it’s going to cost at the end. So you have to pay up-front for the metal works to be made, and the test pressings, and then records to be pressed to secure the price.”

That obviously has an impact on cash flow, which is always an issue for smaller businesses.

The way Cramp set up and runs Sonic Cathedral took considerable entrepreneurial skill. The fact that has notched up 18 years in business is quite an achievement. A birthday event is planned for The Social in London on 20 November, with Andy Bell DJ-ing among other attractions.

But while Cramp isn’t in it to get rich, the label still needs to wash its face. Inevitably, some of those price rises have to be passed on.

Cramp is genuinely regretful about this: “I try to keep prices down but you obviously have to be sensible otherwise there wouldn’t be a business. Obviously, profit margins are being squeezed. I hadn’t really looked at those figures before talking to you. Looking at them now…”

Indeed so. This has implications for the vinyl revival – the rebirth of the old format which has become an increasingly important source of revenue for artists particularly given the poor returns available from streaming.

“I really don’t want to sound too negative but I fear that it’s already hit. Maybe the spike that we saw during Covid was like a death throw thing rather than a new beginning. Sales have certainly gone down in the latter half of this year.

So many things now just don’t turn up when you send them out. I’ve posted three copies of a record to this guy in Germany

“People’s behaviour is changing too. They seem to be more cautious. They are less likely to pre-order. It’s the same with gigs as well. People aren’t buying tickets until the last minute because they’ve got into the habit of doing that with things being cancelled and Covid. None of this makes it easy and it wasn’t easy in the first place.”

This brings us back to Brexit, which is the thundercloud in the middle of a perfect storm, the one thing a small outfit does not need with the million and one other problems that have emerged to bite it.

“The customs is all done through the company I use to press vinyl,” he says of one of the big problems with the Conservative Party’s economically disastrous project. “But loads of things have changed. The biggest thing I’ve noticed, which I think is Brexit-related, is that direct sales to Europe have just dried up.

“The last few years have been weird getting records into shops in France and Germany but posting, the stuff I do through Bandcamp, direct to consumers, it’s got really bad. Germany used to be really good and Europe generally did well for us but it’s just dropped off a cliff.”

One of the problems has been created by IOSS testing – that is Imports One Stop Shop. Bandcamp has an IOSS number, which has to be stuck on the parcels those who sell music via the online platform then send out. It is designed to ensure that customers are being properly taxed

“Basically, unless you can prove that you’ve paid the tax at source, the VAT, you are liable to pay when it is delivered to you. That’s put people off ordering. The sticker is to make sure that the person delivering the record knows there’s no tax due but no one seems to understand it.”

Then there is the issue of disappearing records: “So many things now just don’t turn up when you send them out. I’ve posted three copies of a record to this guy in Germany. He reckons up to 50 per cent of unregistered untraceable post doesn’t turn up from the UK because the system is just more complicated than people think.

“I don’t know where the stuff ends up. It’s probably in some customs office or some pile somewhere. So that’s frustrating.”

There’s that understatement again. Most people would probably use more robust Anglo-Saxon to describe what’s been going on. It’s a small-business killer.

“I sent out some T-shirts the other day, I think about 10, and just five went to Europe. That includes Ireland as well.

“I looked at the figures for Mark Peters’ albums. I did one in 2018 and one that’s just come out and I did the percentages. The first one, 18.5 per cent went to the EU. With the new one, it was 9 per cent and I’d say that’s high. These days I’ll be sending more to the United States.

“Other labels have said the same thing. We’ve been talking about how we can handle this, is there some kind of way of having a hub in Europe where you have records delivered to and they’re sent out from there. But it all just seems so backward.”

A giant step backwards indeed. In the days of the single market, it was seamless.

Touring, which is an important way for acts to promote their releases through the label, and to raise revenue for themselves, has also taken a hit.

“That, in the more long term, is going to really affect things,” Cramp says. “I know bands that have to list every piece of equipment and where it was bought and how much it cost. Ten pages for every guitar pedal. It’s crazy. Absolutely crazy. Often it seems not to get checked but there’s always the chance it will be, which means you don’t get your gig and you don’t get your money. It sounds a complete nightmare.”

Warming to his theme he explains: “Did you see Animal Collective cancelled their European tour the other day because they said it wasn’t financially viable to do it? They’re not a huge band but they’re big and they have a following. It should be sustainable. They were curating a festival in Belgium. The bill they curated is still happening just without them playing. They’re one of many. I’ve seen loads of bands just cancelling. Everything seems so vague and difficult. It was always hard work. Now it’s just getting harder.”

The short-term catastrophe some predicted after the Brexit vote did not happen. But if anything, the long-term impact of this act may prove more far-reaching, and worse, than anyone feared.

Yet throughout this, Sonic Cathedral abides, through the hard work, dedication and love of its product displayed by its founder.

“I really don’t want to seem too negative,” Cramp repeatedly stresses during and after our talk.

I try to reassure him. He’s just being realistic.

Sonic Cathedral is a grown-up in terms of its age. You would hope that it passes a few more big anniversaries before Cramp is done, despite the best efforts of some of Britain’s politicians and an increasingly difficult world. It will never be too big to fail. But it is too special to be allowed to.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments