The truth about Covid-19 and what it does to the brain

We know how coronavirus affects the lungs... but what about the brain? Long-term side effects include memory loss, trouble with impulse control, and personality change – and the risk is amplified for the poor, report Donné Minné and Mischa Minné

By now, most of us will be familiar with the litany of facts surrounding Covid-19. So perhaps it will come as a surprise to learn of the potential cognitive repercussions for those who become acutely ill to the point of requiring hospitalisation. Somehow, during matters of life and death, our higher mental faculties take a back seat. In the UK, the death toll is more than 43,000.

For South Africa, a recent forecast from a group of researchers from the universities of Cape Town, Stellenbosch and the Witwatersrand is just as sobering, projecting that the country can expect in the region of 40,000 Covid-19 related deaths by November 2020. But as a neuropsychologist, I’m focusing on the brain of survivors and what damage to this special organ will mean for personhood – for your very sense of self – and for cognition – how you process information about the world around you.

A significant proportion of Covid-19 patients who survive the ICU can be expected to sustain lasting damage to the brain. They may have problems with their memory and think in less efficient ways. Many will experience changes in their moods, even in their character. If they are below the retirement age, they will probably not be able to return to work at full capacity.

This is a problem we should be talking about. In a population like South Africa, where poverty has led to poor health, inadequate education and increased psycho-social stress, the ramifications of Covid-19 on the neurological functioning of survivors could be substantial and present additional challenges to their families and communities. We have already seen such scenarios play out with other viral infections, such as HIV and TB, which have proven to be associated with profound deficits in cognitive functioning, especially in older patients living in conditions of impoverishment, which make their brains especially vulnerable to infection.

How does Covid-19 affect the brain?

Survivors of critical illness in intensive care wards often develop “post-intensive care syndrome”, a condition that includes persistent problems in cognition and other symptoms including muscle weakness, paralysis, and intrusive, post-traumatic memories. Without digging any deeper, we can expect Covid-19 survivors to face this hurdle.

Yet increasingly among the scientific community, we are hearing reports about the potential of Covid-19, specifically, to disrupt the functioning of the central nervous system. In studies of prior coronavirus outbreaks, post-mortem studies found traces of Sars-Cov in the brain. Researchers speculate that the virus might enter through the olfactory (nasal) nerves or even cross the blood-brain barrier – a thin layer of cells that prevents harmful substances from entering the brain.

A major cause of neurological impairment in Covid-19 is believed to be the body’s own immune response

Because the keyhole-type structure (a receptor) through which Covid-19 virus enters cells, called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), has been found in the brain, neurons are vulnerable, in theory, to Covid-19. However, there is no definitive proof yet that Covid-19 can directly invade brain tissue in humans. In such cases, we would expect to be seeing what is termed “focal” signs of brain damage, such as paralysis on one side of the body or difficulties with language that would suggest unilateral damage to a specific area or brain structure.

While focal symptoms in Covid-19 patients can appear, these are linked to stroke, which is believed to occur as a result of the virus on clotting factors in the blood. Instead, the vast majority of neurological symptoms in Covid-19 have been of a nature that suggests system-wide illness, such as dizziness, confusion, generalised brain disorder (encephalopathy), and seizure.

A major cause of neurological impairment in Covid-19 is believed to be the body’s own immune response. Immune cells release proteins called cytokines that coordinate the body´s response to infection and induce inflammation. In Covid-19, we are seeing this process in hyperdrive, in what is termed a “cytokine storm”. Cytokines are generally able to cross the blood-brain-barrier, and neuroscientists believe that this occurs so that immune molecules can influence neural systems that promote recuperation from illness, like feeling lethargic and demotivated, which allows you to get enough rest.

As a fundamentally social species, new evidence even suggests that inflammation-causing cytokines have evolved to promote certain feelings that make us seek social connection and help us get the care we need from others when we are indisposed. However, neuro-inflammation in excess is destructive and can damage the brain. Scientists from the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, US, reported a case of acute haemorrhagic necrotising encephalitis in a Covid-19 patient, a rare neurological condition associated with brain swelling, haemorrhage and neuronal cell death, which has been linked to immune mechanisms. Fortunately, cases of direct neuro-inflammation in Covid-19 patients remain rare.

Instead, most of the neurological complications that we are seeing in Covid-19 appear to derive as secondary complications of the immune response to infection, similar to what happens in sepsis – when the body’s immune response to infection turns on its own tissues. One such complication in Covid-19 is acute respiratory distress syndrome (Ards), a condition that accounts for most Covid-related hospitalisations, and this should raise alarm for anyone concerned about long-term outcomes for higher-mental functioning.

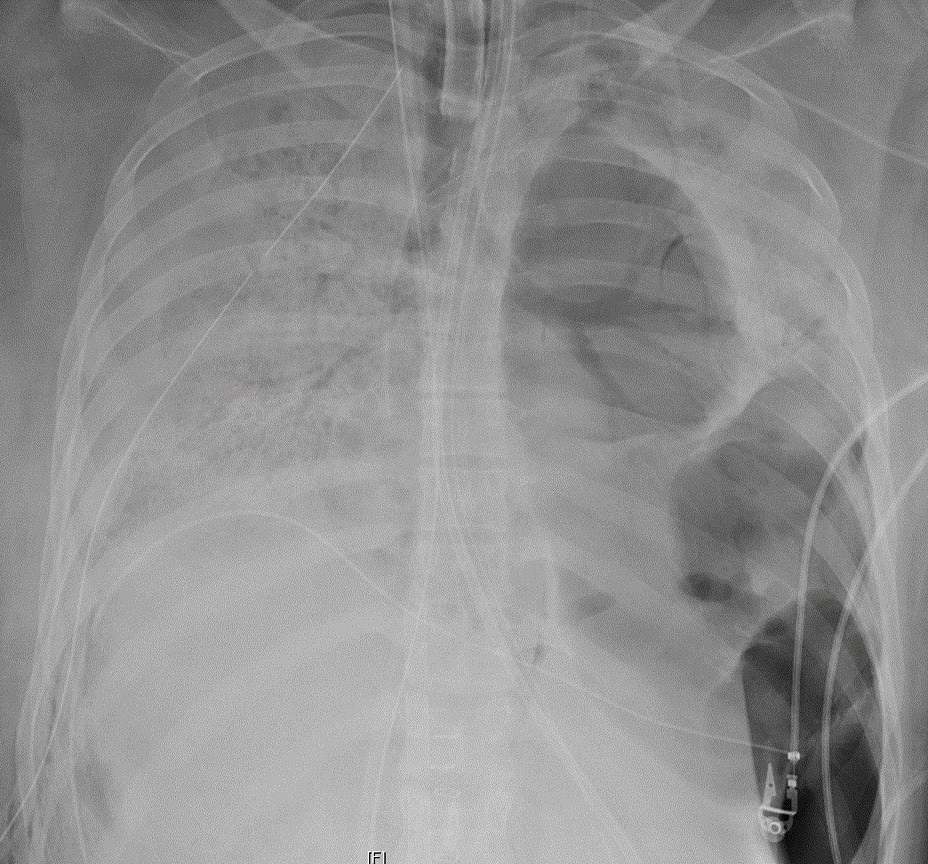

Ards is a severe, inflammatory response, in which the tiny blood vessels of the lungs begin to leak fluid, leading to swelling and respiratory failure. Essentially, it is an extreme reaction to infection in which levels of inflammatory cytokines soar and it can also occur in response to other kinds of critical injury. Breathing becomes impaired and oxygen levels in the blood drop. This is referred to as hypoxemia and it can have dire consequences for the brain.

The brain consumes at least 20 per cent of the body’s entire oxygen reservoir. When respiration falters and the lungs are not able to deliver sufficient oxygen into the bloodstream, brain damage can occur. This is known as hypoxic or anoxic brain injury. Neurons will begin to die after five minutes without oxygen, but damage can occur earlier if oxygen levels are too low for a protracted period of time and depending on individual brain and cardiovascular health.

A recent paper reported that in the sample of 113 Covid-19 patients who died from Ards, 20 per cent had been diagnosed with hypoxic brain injury prior to autopsy. There has been no research yet exploring the impact of this type of brain damage on cognition in Covid-19 patients, but from other studies on hypoxia, difficulties with memory and the functions of the prefrontal cortex are most commonly affected. Damage to this area will leave a person with attention problems, irrational thought, difficulties with abstract thought – the kind of thinking that allows you to appreciate metaphor – and trouble with impulse control as well as problem solving, and changes in mood and personality. These deficits alone mean that a patient will be unable to live independently, requiring extensive assistance in managing their daily affairs.

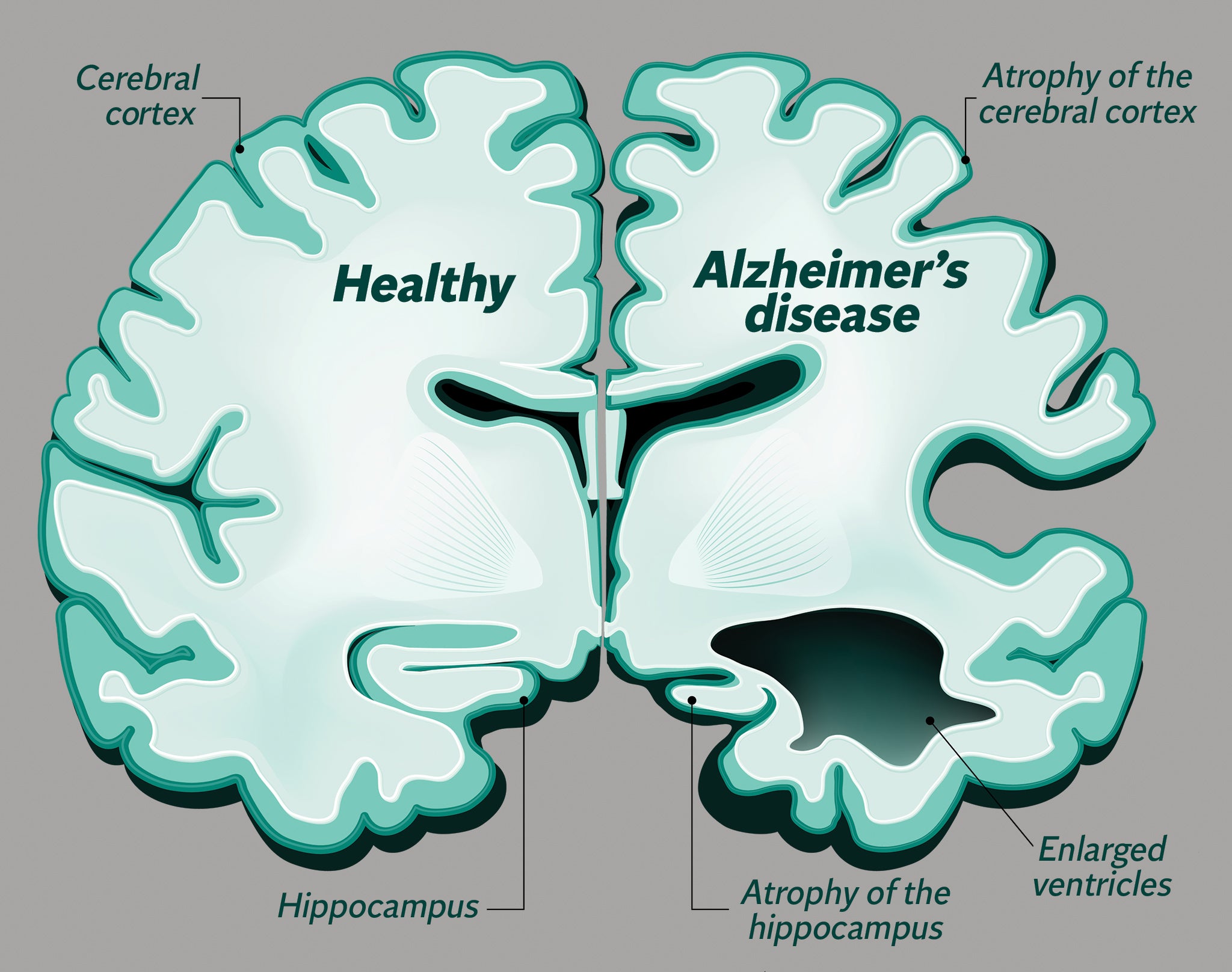

Studies have found that several brain structures are particularly sensitive to oxygen loss. Notable among these is the hippocampus, a tiny seahorse shaped structure that is involved in the formation of long-term memories and is one of the first areas of the brain to degenerate in Alzheimer’s disease. The pathological changes that are detected on brain scans of acute respiratory distress patients tend to be similar to those who have suffered carbon monoxide poisoning or cardiac arrest.

Often, we see damage to a group of subcortical brain nuclei called the basal ganglia. These play a role in the control of voluntary movements and the kinds of motor learning that we don't have to think about, like riding a bicycle. Deterioration in deep white matter tracts is also common, leading to disturbances in the speed at which we can process information and some of our most advanced types of thinking.

Strangely, in Covid-19, doctors have been reporting incidences of “silent hypoxia”, a condition in which a patient fails to experience the normal discomfort as oxygen intake becomes impaired. As a result, they only find their way to hospital when their oxygen levels are critically low. But it is unlikely that silent hypoxia prior to the development of a full-blown episode of acute respiratory distress will result in any lasting brain damage.

In fact, newer research suggests that brain damage from acute respiratory distress is more complex than a simple account of hypoxia might suggest. The root cause of damage may be attributable to inflammatory mechanisms; high levels of cytokines brought on by the infection can alter the blood-brain barrier, changing the way that neurons function and disrupting blood flow to the brain.

Whatever the underlying causes, there are numerous reported cases of cognitive deterioration as a result of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and this body of knowledge offers an important window into what we can expect to see from the current Covid-19 pandemic.

General findings from clinical studies suggest that problems in cognition and personality changes are prevalent in approximately 40 to 50 per cent of acute respiratory distress survivors assessed at one-year follow up, and some are at higher risk for developing dementia in their later years. These patients also tend to report persistent disability in normal daily activities and significant reduction in their quality of life. Fatigue, anxiety, post-traumatic-stress and depression are among the symptoms that have been described in the literature.

Yet as media reports of neurological involvement in Covid-19 are steadily growing, still no one is really talking about what this will mean for the mind – for you, for your unique quirks and traits and talents, and the style of interpretation that makes the lens through which you experience and come to know the world your very own.

We owe this to the brain in its ability to store and retrieve a lifetime of memories and to evaluate, emotionally and analytically, every decision that we must make. If you did not take coronavirus seriously before, perhaps you will now. Brain injury has catastrophic effects on individual well-being and is known to place a costly burden on family and society. For South Africa, managing this influx of neurological patients who are likely to be discharged early from hospitals in the current Covid-19 climate, will require swift interdisciplinary collaborations between medical and community sectors to find innovative solutions to this challenge.

The pandemic has rapidly urged healthcare systems worldwide to reconceptualise their approach to illness and recovery. In the UK, for example, the University College London Centre for Neurorehabilitation has plans to deliver all stroke rehabilitation through virtual platforms, providing essential psychological and physical therapy to these patients from the safety of their homes. While this kind of programme could be a potential beacon of hope for South Africa during the crisis, it will also perpetuate the divide between those with access to costly digital resources and those without.

Donné Minné is a neuropsychologist with a PhD from the University of Cape Town. Mischa Minné has an MPhil from the University of Cape Town in Climate Change and Development

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments