From HIV to coronavirus: Boris Johnson must face ghosts of viruses past, present and future

Having lived as a gay man through the Aids pandemic, I have some advice for the prime minister on how to stop this crisis from becoming a catastrophe, writes Jonathan Cooper

Like many of us, I lived through the Aids crisis. I was in my late teens as the news of this condition that was killing gay men spread. It was first documented in 1981. Being gay, I was terrified. I was just about to come out. I’d started to have sex. I leapt back in the closet and bolted the door. I became simultaneously obsessed with and petrified of Aids. In the end, I became deeply immersed in all aspects of the crisis. I minutely observed the politics. I charted progress in healthcare. Aids became a daily part of life. I didn’t become infected, but I had boyfriends who lived with, and died from, Aids. These were extraordinary times. They were awful. It was all we knew. We didn’t realise how exceptional it was. It was our normal and so we lived with it and learnt our own means of living.

And in its own peculiar way, it was brilliant. It was our Spanish Civil War.

Then in 1995 effective treatment arrived. Almost overnight the hell was over. For well over a decade, we had lived through Aids and then it stopped.

The backdrop to these times in the UK was a Conservative administration. Margaret Thatcher may have ceased to be prime minister in 1990 but the spectre of Thatcherism lingered on through the Major government. She had dictated the UK response to Aids and Major didn’t shift that. Thatcher’s tactics for dealing with Aids turned a crisis into a catastrophe.

Fast forward to 2020 and the Covid-19 crisis and once again we have a Conservative government managing a pandemic. Under Boris Johnson, it is a different brand of Conservatism, but it’s Conservative, nonetheless. This time around, I am in my late fifties. I’m not quite in the most at-risk group for Covid-19, but I repeatedly read how badly men in their fifties fare with the virus. Johnson’s experiences with Covid-19 are testament to that. As with HIV, the virus that causes Aids, so far so good, I remain uninfected by Covid-19 (as far as I am aware). Very good friends have been horribly ill, and some have also lost loved ones.

Living through two pandemics isn’t lost on me. Apologies to Oscar Wilde, and for massacring one of his funniest quotes, “to be at risk from one pandemic may be regarded as a misfortune. To be at risk from two looks like carelessness.” First time round I was left frightened, vulnerable, neglected and marginalised. With the Covid-19 crisis, for people like me – a man in his mid-fifties – they’ve closed the globe to keep me safe.

As with the Aids crisis, like many of us, I am following this pandemic down to the finest detail. I soak up the information, as well as all the crazy stuff too. What is clear is that it is not going the way the prime minister wants it to. I am left reflecting on the two pandemics, both of which exploded out of control. Both crises share much in common beyond the fact that they are caused by viruses. Both have happened on the watch of Conservative administrations, in the UK and the US. Do these health emergencies have to lurch from a crisis to a catastrophe? Is it too late for the UK or can we somehow regain control of the virus? Are there lessons from Aids that can be learnt for Covid-19? Are there lessons from Aids that can help us to prepare for a post-Covid-19 world? Can I help Boris Johnson see this crisis differently? How can I help him learn from Aids?

And then I had my epiphany! What the Dickens, I would take the prime minister on a journey. The path had been laid out for me. Charles Dickens in A Christmas Carol shows Ebenezer Scrooge that it doesn’t need to be like this. That there is another way. I can do the same with Mr Johnson. I can introduce him to the ghosts of viruses past, present and future. Scrooge needed to learn to love again. Dickens’ ghosts showed him that it is never too late to learn how.

As the prime minister grapples with Covid-19, we can meet some of the people, or their spirits, whose work did, or could have, transformed the Aids crisis. We can pay our respects to the people who are making a difference right now and we can observe those who hold the future in their hands. And on the way, we’ll meet with plenty of demons and angels, saints and sinners, heroes and villains. We’ll meet one particular blast from the past from whose failures Johnson can learn to make sure that when Covid-19 is behind us we will live in a kinder, gentler, happier world, in which the priority for us all is maintaining the human dignity of others.

You’ll all recall that before Scrooge was introduced to his ghosts, there was somebody he first had to meet. Scrooge was confronted with his former business partner, Jacob Marley, who had been dead some seven years. Marley had led Scrooge down the path he now finds himself on. Marley is chained for eternity. He urges Scrooge to change his ways and not share his fate. He points out that the chains that imprison him are of his, Marley’s, own making. Johnson must meet his Marley.

By turning on those dying from Aids, Thatcher and Reagan encouraged others to follow their lead. They made compassion for people with Aids, and those most at risk of it, appear weak

Like Marley, Thatcher is weighed down with chains and is destined to languish for all eternity. Thatcher remains controversial but her fate is due only to how she responded to that devastating health crisis nearly 40 years ago.

Instead of acting swiftly to contain the Aids pandemic, Thatcher chose to make political capital out of her alleged hostility towards gay and lesbian people and used Aids as a moral prop to redefine politics. Her bedfellow in opting for this response to the Aids crisis was the then president of the US Ronald Reagan. Together they weaponised Aids and those most affected by it, gay men, and used them to pursue a moral crusade.

By turning on those dying from Aids, Thatcher and Reagan encouraged others to follow their lead. They made compassion for people with Aids, and those most at risk of it, appear weak. They shunned their gay, lesbian and bisexual citizens. Injecting drug users, by definition, as vulnerable as anyone can be, were below contempt. In the early years of Aids, their only strategy for dealing with the crisis was to demonise those with the condition. This combination of hostility and inaction resulted in thousands of American and British people being infected.

The virus that causes Aids became known as a “gay plague”, literally something that white, morally “good” people were untouched by. The people who were most at risk of HIV were disposable.

Reagan didn’t mention Aids in the first five years of the pandemic. His wife, Nancy, was even prepared to spurn her one-time close friend Rock Hudson when he reached out for help.

“If there is a hell both Ronny and Nancy are roasting,” one member of the queer activist group known as the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence presciently pointed out.

This culture of blame for Aids allowed Thatcher’s government to shirk its responsibility for the crisis. She is complicit along with many media villains in using the Aids crisis to vilify and torment. Why did it take a princess to show compassion?

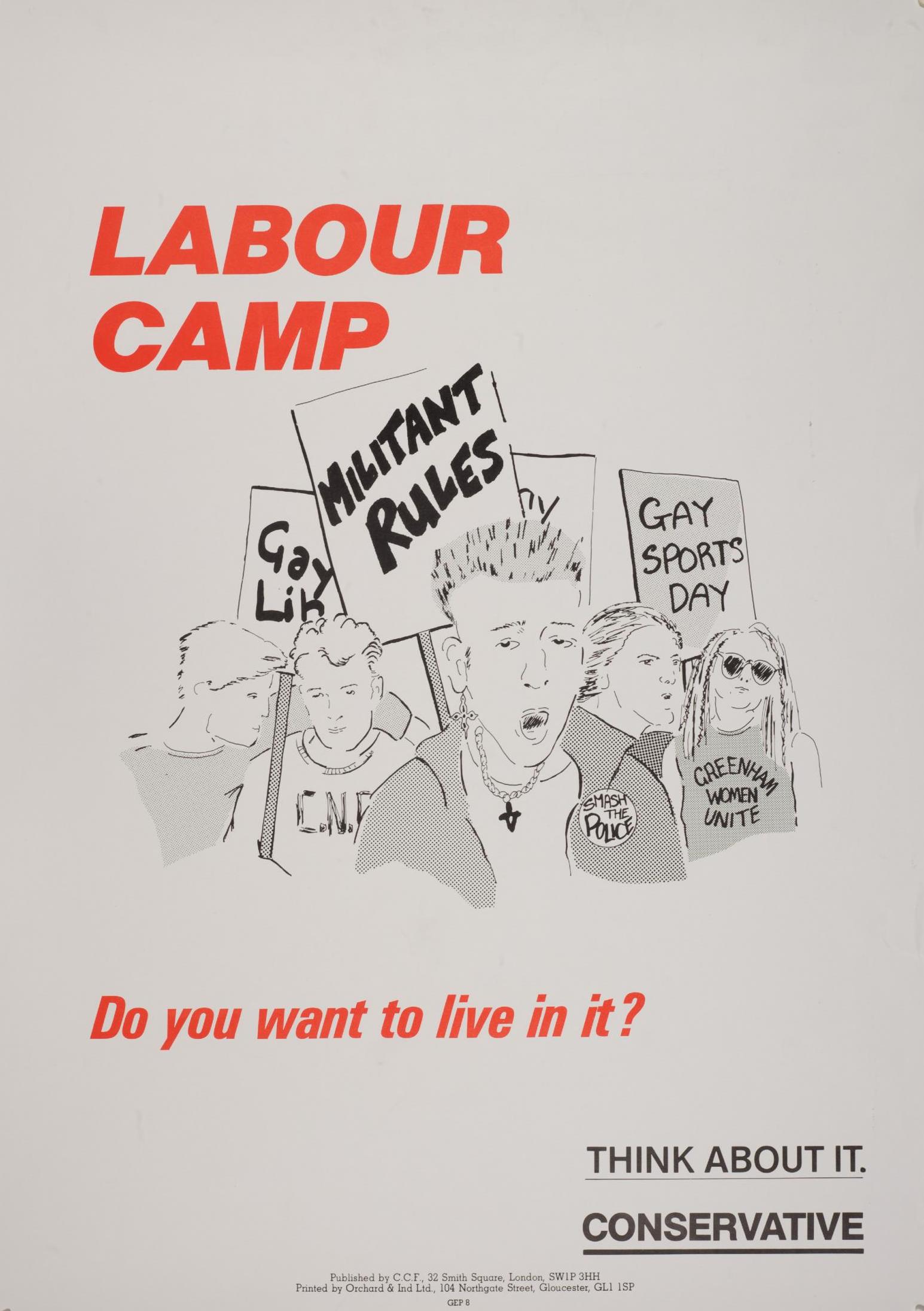

Disgracefully, she was even prepared to make gays and lesbians a party-political issue. Thatcher hyped up anti-gay rhetoric to win the 1987 election. Her election slogans included “This is Labour’s camp, do you want to live in it?” Her intention was to ridicule gay men and lesbians and associate them with the Labour Party to make political capital. The dog whistle link with HIV was deafening.

Not content with mocking gay men and lesbians, at the height of the Aids crisis her government used the power of an act of parliament to isolate and demonise gay and lesbian children. I don’t need to tell you about the horrors of Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 and the consequences of outlawing the promotion of homosexuality.

The provision may have had a limited and meaningless carve-out for health-related concerns, but the harm was done. Too many gay men who grew up through the Section 28 years have told me that their first sexual encounters were frightening and unprotected. Those traumas could have been avoided, and we do not know how many lives were put at risk.

Thatcher’s Britain seemed to revel in the renewal of homophobia. There was that insidious, unequal age of consent. The criminal law was used to reinforce terrible stereotypes of gay men. During this period there were tens of thousands of prosecutions of consenting men who were just seeking a little intimacy with each other. They didn’t need a word for homophobia then. Everyone just was. And then there was the adoption of Section 28 in 1988. Simultaneously, prosecutions peaked.

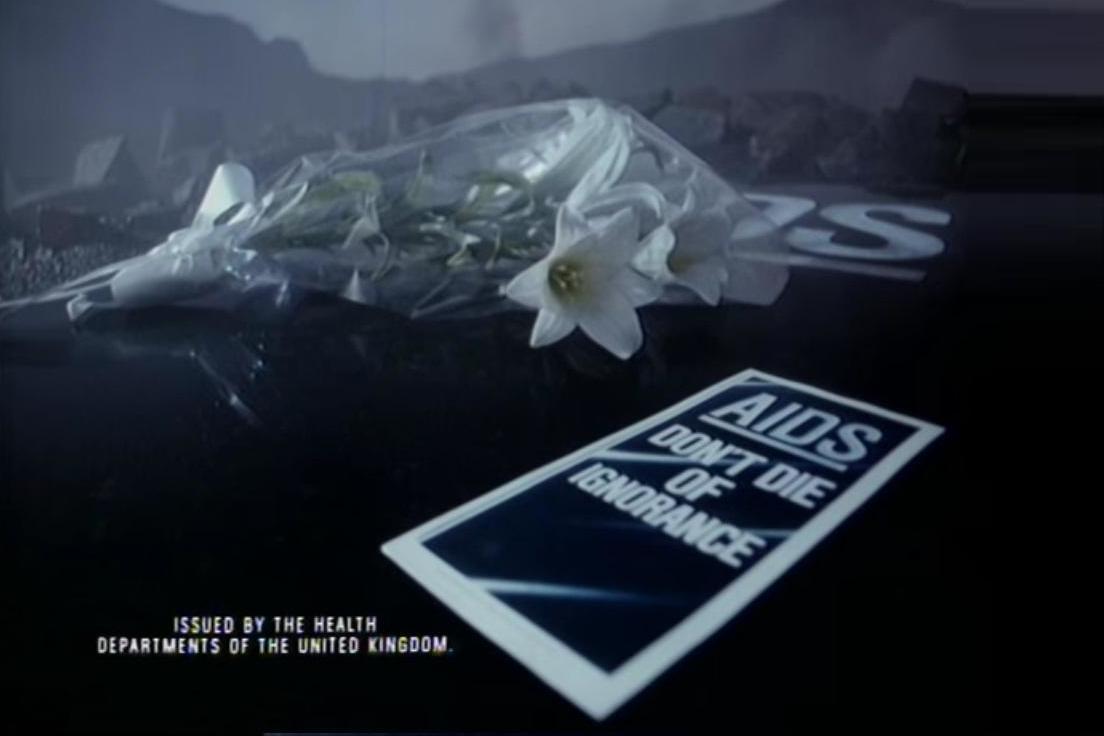

If Thatcher has any respite from her chains, it’s because in 1987 she didn’t stop her secretary of state for health, Norman Fowler, from introducing a massive public health education programme around HIV and Aids, “Don’t Die of Ignorance”. This happened despite Thatcher. My views on it are irrelevant, but I don’t disagree with those who say it could have been a little less frightening, a bit more positive and a great deal more targeted.

Merkel’s immediate grasp of the Covid-19 pandemic was due in part because she understood the science of the crisis. Thatcher, one can only assume, chose to ignore the science

Credit to Fowler, nevertheless, in that lives were saved at the time, but for many it was too late. A government campaign should have been introduced in 1982 when it was clear, for those who chose to see, what was happening.

Why did the scientist choose to ignore the science? Thatcher, like the current German chancellor Angela Merkel, was a chemist by training. Merkel’s immediate grasp of the Covid-19 pandemic was due in part because she understood the science of the crisis. Thatcher, one can only assume, chose to ignore the science surrounding the first years of the Aids crisis.

So many scientists and public health experts were immediately drawing comparisons with the epidemiology of hepatitis B. Why was Thatcher not rolling up the sleeves of her metaphorical lab coat and probing this line of argument? Failure to do so also meant the blood products supply became infected, just as it had already been with hepatitis.

People with haemophilia didn’t stand a chance, and over 60 per cent of them with severe forms of the condition in the UK became infected with HIV. Why was it that Edwina Curry MP, who was later to make the age of consent her cause, was making these links between Aids and blood, but our scientist prime minister chose not to?

One unintended consequence of Thatcher and Reagan’s response to the Aids crisis is that in the absence of support from our elected leaders, the communities most affected by Aids filled the vacuum and took control. Things would never be the same again. Bright and brilliant young lesbians and gay men took on the corporations and the state and demanded that they do better.

Act Up in New York, inspired by the great, late Larry Kramer, revolutionised campaigning and activism. They demanded access to boardrooms, and every level of government, health services and hospitals, social services and hospices. They were unstoppable and haven’t stopped since.

Thanks to the activism of people living with and dying from HIV/Aids, patients became partners in their healthcare. Once the health establishment had been forced to let people with Aids join them around the table, they could not resist the calls from others living with health conditions. Thanks to HIV, the system of accountability of healthcare was revolutionised.

In the UK, Nick Partridge’s stewardship of the Terrence Higgins Trust got so many of us through. Lisa Power provided guidance, leadership, comfort and support.

Christopher Spence, at the London Lighthouse (which provided hospice care and palliative support) insisted no one was to spend their last moments as they died from Aids in a single bed, capturing so intensely the essence of what was happening. There was the wonderful Robin Gorna and our Michael Howard, not the Conservative peer. Michael could be very angry but living with Aids is tiring. Why wouldn’t he be angry? Michael was also able to bring people with Aids together.

And Jonathan Grimshaw added an intellectual clarity to everything that was going on. He, with the powerhouse that is Ceri Hutton, devised and drafted the UK Declaration of Rights for People with HIV and Aids. For the denial of rights of people with HIV/Aids was breathtaking.

People would be made homeless. They would be fired from their jobs. A real fear was being exposed in the press. Kids were denied access to school. A woman I met was advised to have a hysterectomy as well as a termination of her pregnancy because she had HIV. And so many loving couples had their lives ripped apart first by the virus and then by the state which refused to recognise that love.

Did you know any? I knew too many. By the time I was 30, too many people I’d come to know and like had died. I would also lose those whom I loved

How clever Jonathan and Ceri were in devising the UK Declaration of Rights for People with HIV and Aids. They turned Thatcher’s failure to protect on its head. It pointed out that people with HIV/Aids were no different from anybody else and were entitled to exactly the same rights as everybody else. It wouldn’t be long before the idea caught on, and by 1998 we got the Human Rights Act.

But at the time, and for much of the country, Thatcher had set the tone and it would take the best part of two decades to shift it. In the meantime, 10,000 people in the UK died. Did you know any? I knew too many. By the time I was 30, too many people I’d come to know and like had died. I would also lose those whom I loved. We kept up a pretence, but we all knew they died as outsiders.

Thatcher’s government, at the height of the Aids crisis, also introduced silly and unworkable regulations which enabled people with Aids to be detained. In due course, time would also be found to criminalise the transmission of HIV. It doesn’t matter that these laws were and are barely used, they sent out a message about how toxic we were. Thatcher put in place nothing to protect us or look after us.

Reagan’s and Thatcher’s decision to effectively demonise people with Aids had a devastating impact across the globe. Millions were being infected in what we now call the Global South. Her premiership and his presidency are defined by that catastrophe. HIV/Aids became a global crisis.

That global crisis could have been mitigated. By the mid-1980s, world-renown public health expert Jonathan Mann was leading the UN Aids programme. He understood that guaranteeing and protecting human rights would bring the burgeoning global pandemic under control. But he faced constant obstruction from the international community, so that, by 1990, his programme had been neutered. Although it limped on for a few more years, Mann resigned.

Furthermore, US government funding was to be made dependent upon impossible criteria to fulfil, such as abstinence. Republican America projected its values onto one pandemic, whilst Africa lived another. HIV/Aids overwhelmed healthcare systems and economies across the Global South. The failure of leadership was like the virus. It spread everywhere. Thatcher and Reagan were super-spreaders. Too many followed their lead.

Perhaps the greatest example of failure in leadership, which can be traced back to those early years of the crisis, happened in South Africa. Could South Africa’s president, Thabo Mbeki, have pursued the irrational reasoning he adopted questioning the link between HIV and Aids, had the global community got behind Jonathan Mann’s Aids programme in the 1980s? The result was hundreds of thousands, if not millions of deaths. Mbeki’s madness ended only when the human rights contained in South Africa’s new constitution kicked in to protect those at risk from his policies.

Mbeki’s failure raises the spectre of crimes against humanity and the role of the international criminal court. If Mbeki is to be held to account, why not Thatcher and Reagan? There might even be lessons here for Covid-19. If it’s correct that there are tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths in the UK today, should we also be asking whether the most serious crimes have been committed?

As in the Global North, heroes emerged across the Global South. Extraordinary civil society organisations took control in Asia and Africa. Alliance India has ensured access to treatment for people living with HIV. They were also part of the successful campaign to repeal Section 377 of the Indian Criminal Code, which criminalised same-sex relationships.

The Treatment Action Campaign, a movement of people living with HIV, sprang up in the 1990s and forced the government of South Africa to face up to the pandemic levels of HIV in the country, and to start providing life-saving HIV treatment. Their court case led to Mbeki’s resignation. Their work successfully challenged the belief that HIV treatment wasn’t possible in resource-poor settings and inspired a generation of activists across Africa. They also forced drug companies to reduce the price of HIV medicines.

Over the decades these organisations and others like them have flourished. But we shouldn’t underestimate the role played by agencies like Frontline Aids and the Elton John Aids Foundation, which made change happen. And of course, there was that period between 1997 and 2020 when DfID could act as a quasi-independent broker, ensuring that Britain’s taxpayers’ money was put to the best humanitarian effects.

Johnson needs to listen to David Cameron. If nothing else, the decision to disband DfID will profoundly impact the ongoing Aids crisis.

Thatcher’s response to Aids was unforgivable. This wasn’t a debate. With these viruses, HIV or Covid-19, there aren’t two sides to the argument. There’s one objective, and that is to mitigate and to eradicate. She chose to do neither. The challenge for Johnson is how to ensure his legacy differs from Thatcher’s. To the extent that she had a policy, Thatcher’s approach to Aids led to a fiasco. Johnson looks like he’s heading the same way. Scrooge’s fate seemed equally sealed but the ghosts of the past, present and future helped Scrooge see things differently. The grim future was replaced by hope. The same can be true for Johnson. Our ghosts can help.

The ghost of viruses past

Human rights can get us through this global pandemic. Our ghost of viruses past is Eleanor Roosevelt. She, with others, drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), a document which blends economic and social rights with civil and political rights. It is the bedrock of modern understanding of human rights and how they work.

With these viruses, HIV or Covid-19, there aren’t two sides to the argument. There’s one objective, and that is to mitigate and to eradicate. She chose to do neither

Human rights work. A guarantee of human rights allowed Apartheid to end in South Africa and for Northern Ireland to find peace. Everywhere they are used they bring relief. They work in times of peace. They work in war and they work in a health emergency

At the heart of Eleanor Roosevelt’s human rights project is the right to human dignity. Dignity drives the human rights project. People cannot be reduced to things, mere objects. Every life matters. Had Johnson prioritised human dignity as news of Covid-19 emerged, he would have saved thousands of lives.

His speech in Greenwich at the beginning of February, which spelled out his vision for Brexit, will haunt him. His absurd assertion that he will use the free market to overcome the virus took him on a path that led to the denial of human dignity (he prioritised profit over people) and a massive increase in infections. Had he prepared us for the prospect of a lockdown at that point, instead of categorically rejecting it, the UK experience of Covid-19 would have been fundamentally different. He should have put the right to life first. Had he prioritised the right to health, he would have ensured there was an effective framework for dealing with pandemics that put human rights at the centre of any response.

Yet, Johnson took the opposite course of action and, in his early months as prime minister, disbanded the government’s commitment to pandemic control. As pandemics are a feature of life, the decision to do that beggars belief.

It turns out that there is an ethical framework guiding pandemic control in the UK. It was formulated by the Committee on Ethical Aspects of Pandemic Influenza (CEAPI) in 2007. That framework is an attempt at formulating a human dignity-based approach for dealing with health emergencies. It falls short. There is only a fleeting reference to human rights. The European Convention on Human Rights is mentioned in passing. But how rights work is ignored.

Yet the right to life explains how to get through a health crisis. The right to liberty determines the circumstances whereby people might have to be detained. The right to privacy ensures that people’s private life is not sacrificed during a pandemic. And the prohibition on discrimination establishes both negative and positive obligations.

It is these rights which will be used to hold the government to account as people seek answers for what happened during the crisis. Why not plan and prepare with those rights in mind?

To all intents and purposes the New Zealand authorities already had their pandemic under control by the time the UK went into lockdown on 23 March

Sir Henry Brooke, a remarkable judge who sadly died a few years ago, understood how human rights enhance good government. In his view all policies that impact on human rights should be rigorously tested against human rights standards before they are adopted. Failure to undergo that rigour would suggest the policy is fundamentally flawed. In a short-sighted decision, the then House of Lords disagreed with him. He had explained these principles in a judgment he gave in the Court of Appeal. That judgment was overturned.

Had the principles that Brooke advocated been followed, the CEAPI guidelines would have been required to engage with human rights, not merely mention them. The right to life would have driven the approach to be followed during a pandemic. Instead, we are left reflecting on whether so many would have died had human rights been at the heart of Johnson’s response to date. No doubt, the government is bracing itself for the inevitable deluge of cases that will be brought against it.

The wider human rights framework, beyond the Human Rights Act, is equally helpful. Most obviously the right to health and the commitment to ensure everyone has an adequate standard of living should be guiding the government’s response during the pandemic.

There is still time to bring the pandemic under control by recasting the approach to it and ensuring everything done is human rights compliant. It will be surprising how quickly the tracing app will become workable once the guarantee of privacy can be ensured.

The ghost of viruses present

To all intents and purposes, the New Zealand authorities already had their pandemic under control by the time the UK went into lockdown on 23 March 2020. Johnson needs to learn lessons from New Zealand’s prime minister Jacinda Ardern’s approach. Is it a coincidence that what New Zealand is doing in response to the pandemic fits neatly into the human rights framework? Education, health, social security, an adequate standard of living… to highlight just some economic and social rights that are being prioritised during the pandemic by Ardern’s government.

Not to mention that she works constructively with opposition parties. A special parliamentary committee has been established to oversee the pandemic. It is chaired by the leader of the opposition, and the majority of its members are not from the government parties.

The Covid-19 pandemic cannot be divorced from the climate crisis, and our future world order once the virus is under control must learn to work in harmony with the environment

The New Zealand government’s response is being measured and assessed as it’s being delivered. Lessons, therefore, continue to be learned.

One hero to emerge in the UK through the pandemic is the former Tory MP Sarah Wollaston. As a doctor, she understands the science, and as a politician, she respects the need for accountability. She was chair of parliament’s Health Select Committee. She has said: “Trust lies at the heart of handling a public health emergency on this scale… we urgently need a rapid enquiry or parliamentary commission to make sure that we can learn from mistakes and prevent a second wave.”

Brexit must not stand in the way of ensuring the most effective people are managing or overseeing our way through this pandemic. Johnson and Wollaston may have opposing views on Brexit and the Conservative Party, but that doesn’t mean he should ignore her obvious abilities, and those of others who are not part of his inner circle, in assisting the government in getting the country through this crisis.

There is a Maori term, “mana”. It doesn’t directly translate into English but its linked to notions of human dignity. It’s become part of the government culture in New Zealand. Time and time again we see its value. Let mana guide our policies and practice.

The ghost of viruses future

Dicken’s ghost of the future revealed little to hope for. The prospect was bleak. Death loomed. And our future is looking grim too. A whiff of lawlessness hangs over the nation. How has that happened? Is Dominic Cummings the ghost of the future? If you don’t exorcise him, the UK will be in a very precarious, uncertain place.

Cummings has to go. It matters that he breached the lockdown. As Wollaston points out, trust is the cornerstone of effective public health measures. Policing also relies on trust. You can’t be trusted while there is one rule for your team and another for the rest of us.

There is another future. Vanessa Nakate is a young climate crisis pioneer.

She is from Uganda. She’s a graduate in business studies from the University of Makerere in Kampala. At around the same time Greta Thunberg began her campaign in Sweden, Nakate launched her solo movement to get the Ugandan parliament to take the climate crisis seriously. As she points out, the middle classes will be able to find a way around the consequences of the climate emergency. It’s the poor and already disadvantaged who won’t.

Africa is bearing the brunt of that emergency, in much the same way as it still bears the brunt of HIV. Is Covid-19 about to explode across the continent? We need to listen to Nakate. In a recent post about Covid-19 and the climate crisis she said: “The youth climate movement is … taking climate strikes online and staying inside to keep everyone safe. We listened to the science and respected the instructions given to us.

“This is why we expect the … leaders to stop running away from responsibility and take the necessary action. They need to listen to the science to keep us safe. To protect the people at the front lines of the climate crisis. Earth is our home and our responsibility. And they need to do everything they can to protect it. It is time to listen to the science. It is time to unite behind the science and save lives.”

The Covid-19 pandemic cannot be divorced from the climate crisis, and our future world order once the virus is under control must learn to work in harmony with the environment. We know Covid-19 was able to take hold in humans through unregulated wildlife wet markets in China. Once humans were infected from the bat population there, it was a hop, skip and a jump for global infection to occur.

We ignore Nakate when she tells us that the climate crisis and the biodiversity emergency is with us now. Yet, there is no better evidence of this than the rapid spread of Covid-19. Our future post-Covid-19 must be one that works with the environment and respects the rights of all sentient beings. That means we regulate the world on their behalf to ensure that their rights are recognised and upheld. It means that nature has rights along with our right to enjoy the natural world.

As we rebuild our economies over the next few years, the greening of those economies must be the priority. Johnson’s mantra of the moment, “build, build, build”, must be qualified by the climate crisis.

Which brings us back to the right to human dignity. Pandemics violate human dignity. The consequences of the climate crisis undermine human dignity. The unbridled free market economy that Johnson referred to in his Greenwich speech in February diminishes human dignity, as do recessions. There may be a further lesson from Ardern. She has pointed out that “economic growth accompanied by worsening social outcomes is not success. It is failure.” Well-regulated economies putting health, wellbeing and human rights first enhance human dignity.

A real and stark choice now faces the world. Shall we go through a pandemic like this again, and again, and again?

There’s a common thread which links our ghosts in this story, and that is human dignity.

Johnson could ensure that human dignity is at the heart of the UK system of government. He could legislate for it. All public authorities could be required to take human dignity into account in everything they do. That’s all that would be needed for a culture of dignity to take hold. Johnson should adopt the wisdom of Sir Henry Brooke and put in place vigorous scrutiny mechanisms for all policies that impact on human rights.

Don’t make the same mistake as Margaret Thatcher. Don’t become someone else’s Marley. Thatcher could have championed the new social contract that we now enjoy. In the end, it happened despite her. Johnson’s majority may turn out to be his curse. I hope our ghosts will leave him inspired to rethink how we get out of the pandemic and avoid future ones. Be guided by notions of human dignity. Learn from Thatcher’s failures. Her legacy only divides. She used her power to create dissent. Look to unite. Commit to mana. And use those advocacy skills, which are awesome, to lead us to a freedom that will protect, respect and liberate us all.

There’s a reason why Dicken’s A Christmas Carol captured the imagination of the world. It’s human and fallible. It recognises the power of humility, change and redemption. These are as much values for a godless age as they are for people with faith. Scrooge is remembered for his wisdom because he learns the capacity to listen. By listening he learns. And we go on a right rollicking journey with him. Let’s take this journey, as Covid-19 is brought under control, together.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments