After two fatal crashes, can we ever trust the Boeing 737 Max again?

While much of aviation safety is built upon the lessons learnt from past tragedies, Simon Calder finds a healthy obsession with prevention rather than cure

Some aviation tragedies have a single, brutal cause.

In July 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 was hit by a Russian-made anti-aircraft missile fired from rebel-held territory in eastern Ukraine. All 298 passengers and crew aboard the Boeing 777 were killed.

Most plane crashes, though, result from an alignment of unforeseen failures.

In a seminal British Medical Journal paper published in March 2000, University of Manchester psychology professor James Reason laid out the potential for disaster in many complex human activities, including aviation.

Every high-technology system has carefully constructed defensive layers, he argued. Some are engineered; others rely on highly trained men and women; yet others depend on procedures and regulation.

“In an ideal world each defensive layer would be intact,” wrote Professor Reason. “In reality, however, they are more like slices of Swiss cheese, having many holes – though unlike in the cheese, these holes are continually opening, shutting, and shifting their location.

“The presence of holes in any one ‘slice’ does not normally cause a bad outcome. Usually, this can happen only when the holes in many layers momentarily line up to permit a trajectory of accident opportunity.”

As dawn broke at Jakarta airport on 29 October 2018, 181 passengers lined up to board Lion Air flight 610. The routine departure to the Indonesian city of Pangkal Pinang was aboard the latest version of the world’s most successful jet aircraft, the Boeing 737.

As they waited for departure, knowledgeable travellers may have noted the “double-dagger” wingtips, a feature not unique to the Max. What was different: bigger engines than previous versions of the 737, and hoisted higher and further forward on the wing. That decision was the result of the constant quest to make aircraft ever more efficient, to the benefit of the paying passenger, the planet and the planemaker.

Boeing could have come up with a clean-sheet replacement for its most popular aircraft. The result would have closely resembled the best-selling A320 made by its arch-rival, Airbus.

The US manufacturer chose instead to offer its hundreds of contented existing 737 customers the prospect of a more cost-effective version of the reliably profitable plane. The basic design was already proven, and the look and feel of the flight deck would be reassuringly familiar for pilots – removing the necessity for expensive additional training that is required for new kit.

Two of the world’s most successful airlines, Ryanair of Ireland and Southwest of the US, were eager buyers. Each carrier has an outstanding safety record. Ryanair has flown around 1.4 billion passengers without a single fatal accident, far more than any other airline.

346

people killed in the Boeing 737 Max crashes in 2018 and 2019

That title was previously held by Southwest, until 17 April 2018. On that day, a passenger named Jennifer Riordan took seat 14A aboard a New York-Dallas flight. It was operated by a Boeing 737NG (“Next Generation” – though now it is the previous generation of the plane). Part of the port engine housing disintegrated and hit the fuselage just where Riordan was sitting. She died from her injuries after being partially sucked out of a window.

Applying Professor Reason’s “Swiss cheese” analogy, two engineering weaknesses – a cracked turbine blade and a previously unidentified vulnerability in the housing – conspired with tragic results. Heavily used 737NGs are being inspected and a fix implemented to try to avert any similar combinations of circumstances.

While much of aviation safety is built upon the lessons learnt from past tragedies, there is a healthy obsession with prevention rather than cure. The constant challenge for aircraft designers: “What if …?”

After Boeing decided to continue to exploit the 737, those challenges duly began. To prevent the risk of an engine striking the ground, the bigger engines had to be lifted and moved forward to be blended with the wing.

You might guess this would make the aircraft “nose-heavy”. In fact, the engine housings generate lift and could, in some circumstances, tilt the aircraft upwards.

What if this effect were so pronounced that it caused a stall, in which the wings produce insufficient lift to keep the plane flying safely?

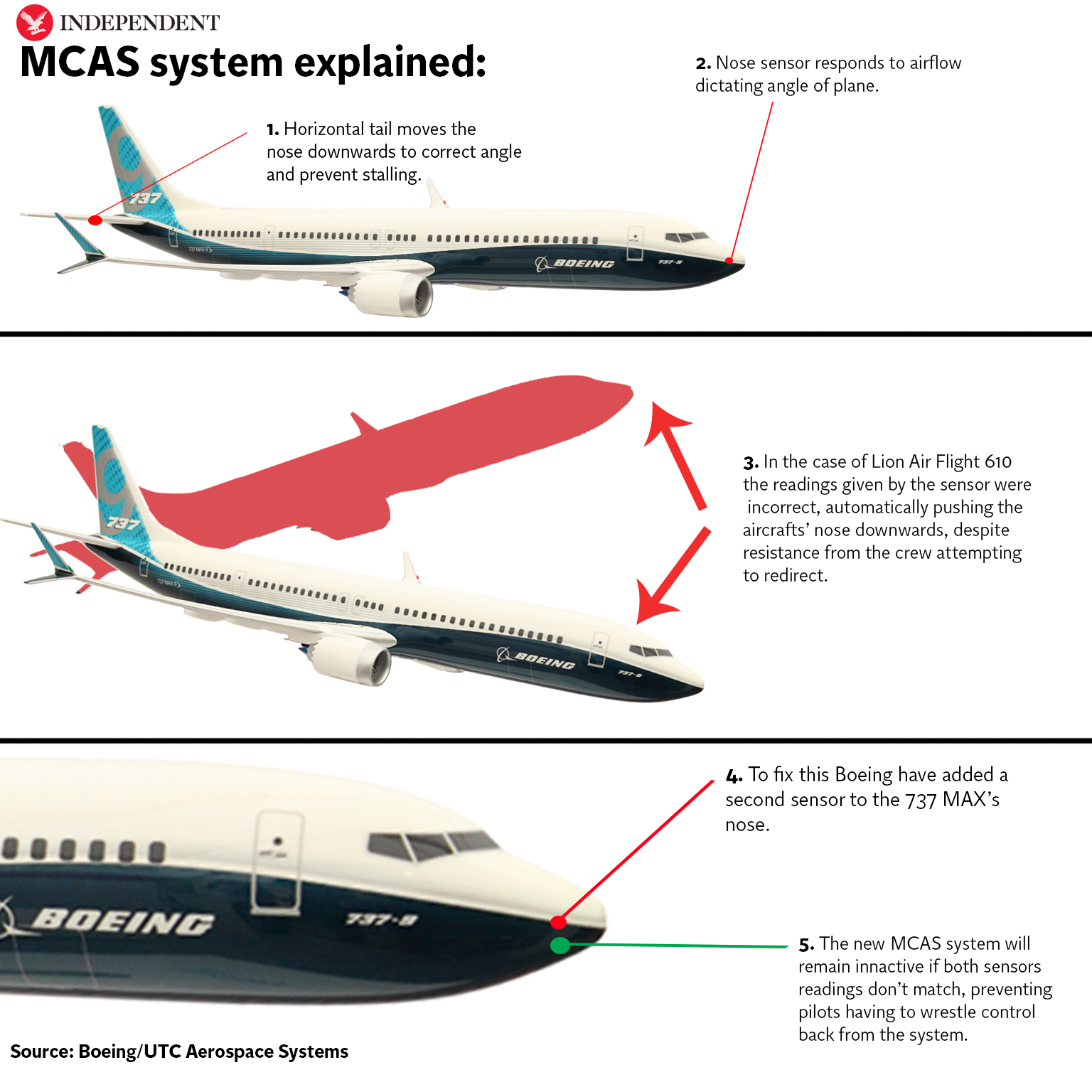

To tackle that possibility, Boeing’s engineers devised a suite of software with an innocent-sounding name: “Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System” (MCAS).

The system monitors one of the key measures in aviation: the “angle of attack”. This is the angle between the wing and the airflow. The higher it is, the greater the risk of a stall. The sensor used is fitted close to the nose of the aircraft.

On the Air France Airbus A330 flying from Rio to Paris in June 2009, inappropriate commands from an inexperienced pilot pushed the angle of attack to 30 degrees, and precipitated a stall from which the jet could not recover. All 228 passengers and crew died when the plane plunged into the Atlantic.

If Boeing’s MCAS detected too steep an angle, it triggered an elevator in the tail to nudge the nose downwards. And it was designed to repeat the “augmentation” relentlessly until the reading normalised, or the pilots took action.

What if the sensor gives a false reading, creating a hole in the defensive layer?

Boeing had an answer for that: the pilots. They were supposed to hold the control column firmly, switch off the autopilot (if it was engaged) and set the two big toggle switches labelled “Stab Trim” to “Cutout”. They could then fly the aircraft manually.

Since this was a recognised and trained-for remedy for “runaway trim”, the planemaker argued, there was no need to tell pilots who were switching from 737NGs to the Max version about the anti-stall protection.

The firm installed a new system for which the failsafe comprised the pilots – but chose not to tell them about MCAS. “If it malfunctions, they’ll know what to do,” was the assumption.

What if all hell has broken loose on the flight deck?

Tragically, no one appears to have asked that crucial question. If a sensor is giving a wildly inaccurate reading, then there is a high likelihood that the pilots will be distracted by other alerts and indications.

Almost as soon as the Lion Air flight was airborne, the captain and first officer were confronted by conflicting readings on two critical measures: airspeed and altitude.

You didn’t tell the pilots that MCAS was in there. Then you added an extra step that would trigger it again five seconds later. Pilots know that catastrophes don’t happen in a vacuum

The final 11 minutes of the lives of the passengers aboard the Boeing 737 Max do not bear thinking about.

A combination of the relentless MCAS activation – repeatedly forcing the nose down – and the pilots’ reaction to bewildering circumstances caused the plane to climb, descend and turn at an increasingly frenetic rate.

MCAS successfully prevented a stall. Instead, the system caused the aircraft to plunge into the Java Sea at a speed of 415mph.

Boeing’s presumption that pilots would respond quickly and effectively proved fatally wrong.

The final report into the Lion Air crash said: “The absence of information about the MCAS in the aircraft manuals and pilot training made it difficult for the flight crew to diagnose problems and apply the corrective procedures.”

When Dennis Muilenburg, CEO and president of Boeing, appeared before a congress committee, one senator put it more succinctly.

“You didn’t tell the pilots that MCAS was in there,” said Tammy Duckworth, the Illinois Democrat. “Then you added an extra step that would trigger it again five seconds later.”

Duckworth is a former Army helicopter pilot. “Pilots know that catastrophes don’t happen in a vacuum,” she said.

The Indonesia accident investigators concluded that what happened on the flight deck was the final component in a series of nine mistakes and misfortunes that lined up that morning in Indonesia – permitting, in Professor Reason’s words, ”a trajectory of accident opportunity”.

The job of eliminating holes in layers of defence rests with the regulator. As Boeing is American, it is watched over by the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). But the more the world learns about the safety sign-off of the Boeing 737 Max, the more it looks as though this defensive layer of “procedures and regulation” itself was full of holes.

Boeing introduced a new system that took power away from the pilots, and then persuaded the FAA there was no need to mention MCAS as one of the differences between earlier versions of the Boeing 737 and the Max.

The planemaker had told the FAA that MCAS was designed to move the nose down by 0.6 degrees. But in subsequent tests it appeared to Boeing that the aircraft needed more of a nose-down push in order to recover. The movement was increased to 2.5 degrees. And the penalty for failure increased – fatally.

The first time the American safety regulator took any action on MCAS was nine days after the Lion Air crash, as the black boxes revealed the horrific sequence of events.

In an Emergency Airworthiness Directive, the FAA warned that the anti-stall system “could cause the flight crew to have difficulty controlling the aeroplane, and lead to excessive nose-down attitude, significant altitude loss, and possible impact with terrain”.

Airlines were told to update their flight manuals “to provide flight crew with runaway horizontal trim stabiliser procedures to follow in certain conditions”.

But the Boeing 737 Max kept flying.

On 10 March 2019, Captain Yared Getachew and first officer Ahmed Nur Mohammod Nur were assigned to Ethiopian Airlines flight 302, the first departure of the day from Addis Ababa to Nairobi. The carrier is regarded as Africa’s most professional airline.

As the Boeing 737 Max took off with 157 passengers and crew, a bird flew into the angle-of-attack sensor, destroying it. As it was designed to do when presented with an extreme reading – genuine or not – MCAS took control.

The pilots appear to have followed the emergency procedures to the letter. But the anti-stall system continued its robotic duty. They tried the stipulated manual technique. It failed to work, and MCAS deployed with a strength to defeat two fit young men. The aircraft was at an angle of 40 degrees when it hit the ground at a speed of 575mph.

Our review shows no systemic performance issues and provides no basis to order grounding the aircraft

But the Boeing 737 Max kept flying.

In the days that followed the crash, investigators quickly identified the role of MCAS. Aviation authorities around the world, including the UK’s highly respected Civil Aviation Authority, banned the Boeing 737 Max from their airspace. They acted to protect passengers, crews and people on the ground.

But the Boeing 737 Max kept flying in the US, complete with a fresh endorsement by the FAA: “Our review shows no systemic performance issues and provides no basis to order grounding the aircraft.”

By the time the FAA reversed its decision and issued a grounding order, 24 hours later, the regulator’s authority was already in shreds.

We now know that, when it should have been challenging Boeing, the FAA was colluding with the planemaker’s plan to minimise the apparent scale of changes brought in by the Max.

After the Lion Air crash, the organisation could have delved deep into a safety system that had proved tragically capable of applying an unstoppable force to down an aircraft. Instead, the FAA reiterated Boeing’s conviction that any pilot should have the wit to overcome a malfunctioning MCAS.

With its new-found interest in every detail of the planemaker’s designs, the FAA has taken its time in giving a green light for the Max to return to the skies. It will happen in the new year. When the Boeing 737 Max flies again, the defensive layers Professor Reason described will be far more robust.

Engineers have detoxified MCAS: it will still be in the background, but in any human vs machine tussle, the flight crew will now prevail.

Those pilots will be thoroughly versed in the system, now that Boeing has reversed its “nothing to see” stance on converting from old to new 737s.

Whether the public will feel reassured remains to be seen. In June 2019, more than half the respondents to a Twitter poll by The Independent said they would not fly on a Boeing 737 Max. I am not among them: I look forward to stepping aboard the jet after safety officials have done what they were supposed to do. But making the plane safe has come at an unacceptable cost. It must never happen again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments