Musical genius Elgar hated the nationalistic Land of Hope and Glory

Elgar’s famous composition was instantly dismissed by some as ‘cheap’ and ‘unworthy’. But it was a huge success at the Proms, where crowds rose and yelled and demanded it be played three times. Andy Martin on the man behind the music

Even Elgar got sick of it. Despite which, masses of us will be singing along on the last night of the BBC Proms at the Albert Hall, with backing from the BBC Symphony Orchestra, to the Pomp and Circumstance March no 1 in D Major, “Land of Hope and Glory”. There will also be a rousing rendition of “Rule Britannia!” But “Land of Hope and Glory” is still one of the most patriotic songs imaginable, an alternate national anthem.

Elgar wanted to bin it. I agree with him.

It started life in 1901 as a march without words, first performed in Liverpool. It then morphed into the “Coronation Ode”, for the coronation of Edward VII, the following year. Elgar, then styling himself “Dr Elgar” after receiving an honorary doctorate from Cambridge, soon to be Sir Edward, was in the frame for a knighthood and the ode wouldn’t do him any harm. AC Benson (who taught at Eton and would become Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge) wrote the lyrics to go with it. His original version started like this:

Land of Hope and Glory

Mother of the Free

How may we extol thee

Who are born of thee?

Truth and right and freedom

Each a holy gem

Stars of solemn brightness

Weave thy diadem

Perhaps those words were just a little too metaphorical. What was he going on about exactly? This was the time of the Boer War in South Africa and the nation was feeling particularly gung-ho. So the publishers asked Benson to do a rewrite and make it more popular. He duly obliged, inspired by the massive legacy Cecil Rhodes – having plundered “Rhodesia” and South Africa – had bequeathed to a grateful nation for the further expansion of the empire (“the extension of British rule throughout the world”). It became, in other words, not just nationalistic but more manifestly and transparently imperialist and colonialist.

Try this for a singalong:

By Freedom gained, by Truth maintained

Thine Empire shall be strong

Land of Hope and Glory, Mother of the Free

How shall we extol thee, who are born of thee?

Wider still and wide shall thy bounds be set

God, who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet

God, who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet

It goes on about “fame” and the “Ocean” and “a stern and silent pride”:

Not that false joy that dreams content

With what our sires have won

The blood a hero sire hath spent

Still nerves a hero son

Those last few lines bear re-reading. Unless I am completely misinterpreting, our Etonian master is recommending that his pupils need to emulate (male) heroes like Rhodes et al and go out and steal the world for Britain. Whether at the cost of their own blood or, more likely, someone else’s. It provides a working definition of that good old word “jingoistic”, which itself derives from another music-hall song, written in the 1880s, taunting Russia:

We don’t want to fight but by Jingo if we do

We've got the ships, we've got the men, we've got the money too

We've fought the Bear before, and while we're Britons true

The Russians shall not have Constantinople

As I discovered in Richard Westwood-Brookes’ recently published, wonderfully researched book Elgar and the Press, Elgar’s composition was instantly dismissed by some as “cheap” or “unworthy”. The Musical News reporter described it as being “spirited-exciting-throbbing-pulsing almost maddening in its insistent rhythm”. Elgar himself clearly fell out of love with it, partly because it stereotyped him as a tub-thumping, flag-waving advocate of war, or, as he put it, “we are a nation with real military proclivities [and] I have some of the soldier instinct in me”.

But it was an instant success at the Proms, under Sir Henry Wood. Wood later recalled: “The people simply rose and yelled. I had to play it again – with the same result; in fact they refused to let me go on with the programme. After considerable delay, while the audience roared its applause, I went and fetched Harry Dearth who was to sing ‘Hiawatha’s Vision’; but they would not listen. Merely to restore order I played the march a third time. And that, I might say, was the one and only time in the history of the Promenade concerts that an orchestral item was accorded a double encore.”

Fame is a form of incomprehension. Elgar is one of those figures who succeeded in typecasting himself. He really was a country boy at heart but he turned nostalgia into a career. I went back to where he was born, in the village of Broadheath, a few miles outside Worcester, to the gorgeous little cottage known as The Firs, now owned and lovingly restored by the National Trust.

The garden alone is worth the visit. But inside you can find some of his treasures, the desk he worked at and his double-sided music stand (for playing with friends) and the five-nibbed pen he used to write out his own staves (his wife didn’t want him wasting money on manuscript paper). Elgar left here when he was only two. His parents took him off to the big city of Worcester, where his father was a piano-tuner and owned a music shop (“The Elgar Brothers”) and he always harked back to it as the presiding source of his inspiration.

He used to come back and sit in the garden – he had to ask the owners permission – and look out over the Malvern Hills in the distance and dream up another gorgeous piece of music, shot through with melancholy and yearning and mysticism, from the violin and cello concertos to The Dream of Gerontius. As Elgar said in 1921, when he was 64: “I am still at heart the dreamy child who used to be found by Severn side with a sheet of paper trying to fix the sounds and longing for something very great. I am still looking for this."

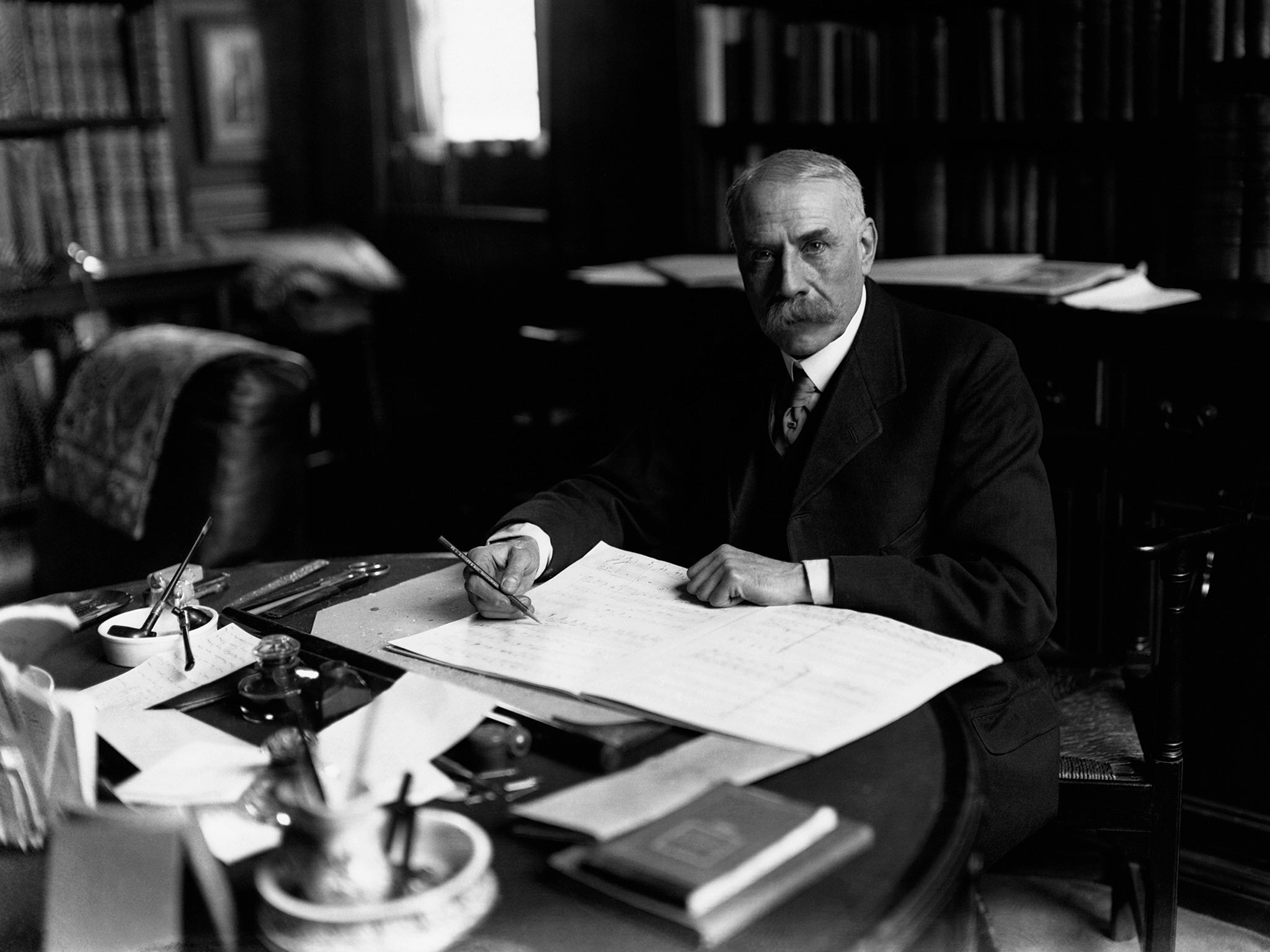

People mocked the idea that there could be another “enigma” melody, as he suggested, beneath the actual melodies you can hear in the Enigma Variations. But it is not so ridiculous to think that there is a more enigmatic figure beneath the almost too familiar image of the buttoned-up, bewhiskered Victorian gentleman, sometimes seen with a bicycle, whose music has become synonymous with Britishness.

He was a self-taught musican who started out as a violin teacher and church organist. He painted an idyllic picture of his musical education. “I remember distinctly the day I was able to buy [the score of Beethoven’s] Pastoral Symphony. I stuffed my pockets with bread and cheese and went out into the fields to study it. That was what I always did.”

His younger brother, Frederick, who died aged seven, was the prodigy, “little Mozart” as they called him, who was expected to succeed, not his big brother. Elgar was an outsider: not from London, and a Catholic. He took a series of jobs, such as composing quadrilles and polkas for the Worcester and County Lunatic Asylum and had to claw his way up the establishment ladder, then dominated by academic composers. He personally wrote – as Westwood-Brookes points out – a lot of the early press releases himself, saying how great he was. Perhaps he really was a “genius”, and the “greatest English genius since Henry Purcell”, but the DIY spin hardened into a myth that he could never quite shake off.

Caroline Alice Roberts, daughter of Major-General Sir Henry Roberts, and eight years his senior, was one of his piano students. They married in 1889, honeymooning on the Isle of Wight. She became not just his wife but his business manager and his agent, obsessed by massaging his image. As she wrote in her diary: “The care of a genius is enough of a life work for any woman”. Kirsty Bothma, who is the visitor experience manager at The Firs, says: “There is almost no photograph of Elgar that is not in some way stage managed.” He is never seen wearing glasses, for example. The hair is always carefully combed over, Bobby Charlton style. He wrote her a love song, “Liebesgruss” (“Love’s Greeting”) – knowing her to be fluent in German – but she persuaded him to retitle it “Salut d’amour”, just to be on the safe side.

When Alice died in 1920, Elgar found consolation in his dogs, Marco, Mina and Meg (she didn’t like dogs) and they are buried here at The Firs. But his music more or less dried up. Somehow his creativity and his self-image were interdependent.

His daughter, Carice – her name was the nickname he gave to his wife, merging her two names – took over the job of preserving and protecting his sacred reputation. For starters she went about collecting letters and diaries and then burned or destroyed any that didn’t fit. She was particularly keen to quell any scandalous talk of lovers (there was another “Alice”, Lady Alice Stuart Wortley, daughter of the painter John Millais, and something of a classic Pre-Raphaelite beauty herself). Elgar may have had a series of “muses” (in Kirsty Bothma’s phrase), such as Mary Lygon and Dora Penny and Julia Worthington, but Carice had been a censor during the war and more or less carried on the propaganda campaign afterwards.

Elgar imagined his own death. He had a death-mask cast years before and months before he died he commissioned a photographer to take decent photographs of him lying in his “death bed”. He wasn’t exactly a control freak, more a victim of his own controlling nature. Elgar was great friends with George Bernard Shaw, one of the genuine intellectual rebels and freethinkers of the early 20th century. They even travelled together. Elgar described Shaw as the only man “who had been kind to [him]”. Shaw was a surfer who surfed in Cape Town. Kirsty Bothma asked the intriguing question: “Could Elgar have been a surfer?” The answer, I think, is no, because he wouldn’t have wanted to be a photographed without all his kit on.

Elgar was his own greatest creation. He became one of our symbolic Victorians and Edwardians. But he came a cropper with “Land of Hope and Glory”, “essentially British in origin and character” according to The Daily Telegraph (1902). He tapped into a nationalistic hysteria from which we have never fully recovered. During the First World War he wrote patriotic compositions for war charities, music to rally the troops, and joined the Hampstead Reserve Volunteers. But in his battle with German music, it was like he was enacting the war even before war started. It was Elgar vs Wagner. Even the great Richard Strauss allowed that he was “the first English progressive musician, Meister Elgar”. He became Britishness incarnated in musical form.

Ironically, when he took the post of Peyton professor of music at the University of Birmingham from 1905-8, he was damning about English music. In one of his more controversial lectures, he said that “an Englishman will take you into a large room, beautifully proportioned, and will point out to you that it is white – all over white – and somebody will say: ‘What exquisite taste’. You know in your own mind, in your own soul, that it is not taste at all, that it is the want of taste, that is mere evasion. English music is white, and evades everything.”

Perhaps he was trying to surf away from all that, but his music would be indissociable from whiteness. On 28 April 1923 the old Wembley Stadium was officially opened. It was then known as the Empire Stadium. George V was on hand to cut the ribbon. And who was there to provide the musical accompaniment? None other than our very own embodiment of “the English style” (as The Daily Mail put it). But Elgar wasn’t too happy about it. He had lots of new stuff in his head, but, he complained: “All the king wants is ‘Land of Hope’”.

Elgar was a keen football fan and follower of Wolverhampton Wanderers – and even composed an anthem for them, “He Banged the Leather for Goal”. He thought that Wembley ought to be for football and not for nationalistic pageantry. Perhaps something similar could be said of the Proms. And of politics at large. Nationalism is only narcissism on a very large scale.

The National Trust has a five-year lease on Elgar's birthplace in Broadheath, The Firs. Their ability to keep it open for future generations to enjoy is dependent on people coming through the doors

Richard Westwood-Brookes, Elgar and the Press: A Life in Newsprint, is out now

Andy Martin is the author of With Child: Lee Child and the Readers of Jack Reacher, published by Polity

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments