‘It was dangerous work’: The forgotten women of the Battle of Britain

Twelve years after women won the right to vote, their place was still thought to be the home. That is, until 50 of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force helped win the Battle of Britain, writes Mick O’Hare

Air vice marshal Keith Park was unsure. The man whom the Germans would later term “the defender of London” had been informed that women would be working in his operations room deep in the bunker at RAF Uxbridge. The bunker was the nerve centre of Royal Air Force activity during what would become known as the Battle of Britain, which was fought 80 years ago this summer. The German invasion of Britain was imminent and Park was concerned that women at Uxbridge and on operational airfields could come under enemy fire. And while he trusted their accuracy as operatives he wondered how they might react. Would they succumb to stress? Were they up to the rigours of war and the pressure it would bring? What if they left the service and spoke about what they knew? Today, it all sounds a little like stereotyping but in 1940 social attitudes were very different, and this was the first time women had been offered such a prominent role in the war effort. Park was told he had no choice, at which point he demanded three women for every two men they would replace.

By the end of the battle, he had changed his mind. Emphatically. Without you, achieving victory would have been far more difficult, he told them. Their “resolute concentration” even at the most “strenuous of times” was a vital part of the defence of the nation.

Together they had come through an extraordinary few months. When prime minister Winston Churchill addressed the House of Commons on 4 June 1940 he described the mass evacuation of British troops from the beaches at Dunkirk as a “colossal military disaster”, adding on 18 June: “We can assume that the enemy will now turn its attention on us. What General Weygand called the Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin.” He was, of course, prescient.

The German high command codenamed the planned invasion of Britain “Sea Lion” and in preparation for sending their troops across the English Channel the German air force, or Luftwaffe, intended to assert air superiority over the RAF. Airfields and aircraft factories were to be bombed until inoperable and as many British aircraft destroyed as possible.

It would be the first military campaign to be fought solely in the air, and the RAF was already hugely outnumbered. In July 1940 the Luftwaffe could call on around 2,600 aircraft; the RAF had fewer than 2,000, but only around 900 of these were the fighter aircraft that would be needed to repel the German attacks. It seemed that German supremacy in the air was almost a given and acknowledged as such by RAF Fighter Command’s commander-in-chief Hugh Dowding. In a letter to the prime minister dated 16 May the air chief marshal wrote that squadrons of fighter aircraft had been deployed to France and lost in the rearguard action there. He reminded Churchill that an estimated 52 fighter squadrons were needed to successfully defend Britain, and that he now only had the equivalent of 36. He feared the “complete and irremediable defeat” of Britain. For its part, German High Command expected that Britain’s air defences would be overrun within four weeks.

In charge of 11 Group, essentially defending London and the southeast of England – the region where the battle was likely to be most intense – was New Zealander and decorated First World War flying ace Park. He was based at RAF Uxbridge and more pertinently its operations room buried 18 metres, and 76 steps, below a gently sloping hill. It’s now owned by Hillingdon Council and you can still visit today (Covid-19 permitting – the bunker’s website will detail its eventual reopening). In the main operations room what is left of an enormous table map of southeast England fills the centre of the space. On one wall are tote boards listing the airfields and squadrons of RAF fighter planes – the now-famous Hurricanes and Spitfires – carrying systems of lights to show whether a squadron was on the ground, refuelling, airborne or engaging the enemy. On the table below plotters, using long poles, acted like croupiers, moving wooden blocks about the map, noting the position of incoming German attacks, their height and the number of aircraft while other blocks showed similar information on the RAF fighters sent out to confront them. Arrows on the map showed the flight paths of aircraft, colour-coded to show how recent the information was. The work was arduous: it had to be accurate and updated minute-by-minute via telephone to the tellers wearing headphones who passed the information on to the plotters.

The women were from diverse backgrounds and educations and from all over the country. What mattered was their aptitude for the task. A bank clerk might be working next to a novelist

And the plotters and tellers were all women. It had been only 12 years since they had won the right to vote in Britain, and their role was still considered one of domesticity by wider society, but the onset of the Second World War the year before had seen limited opportunities for emancipation as men were conscripted to fight and occupy frontline roles. Women had begun farming (the “land girls” of the Women’s Land Army) and filling other roles in the workforce previously occupied by men such as bus drivers, mechanics, munitions workers and air raid wardens. They also began to play roles in the armed forces. The Women’s Auxiliary Air Force had been created in 1939 to help fill non-combat roles and it was in January 1940 at the insistence of the Air Ministry that women had been deployed to the operations room at Uxbridge.

Whatever Park’s personal reservations, four-fifths of his 60-strong team were women, with as many as 20 (10 tellers and 10 plotters) at any one time working in “the hole”, as it came to be known. Fred Pickard works at the bunker today as a volunteer tour guide. “The job was tiring, pressurised and intense,” he explains. “Total concentration was needed. Shifts were eight hours but once your plot [of a German or RAF squadron] was on the map you had to stay until it had departed. So that could add an extra couple of hours to the shift, and there was no changeover of shifts during hostile enemy action.” Precision was vital. The map was divided into 10-kilometre squares – if an incorrect square was identified, the RAF interceptors could miss their target by a large margin. Although personal diaries were forbidden at the time, one of the women who worked in “the hole”, Amy D’Ernée Mates, later wrote: “The only sound was the click-click of the rods and, occasionally, the voice of the controller quietly calling up more fighters from the flight stations.” And in many ways, the women felt one step removed from the battle. Plotter Joan Fanshawe wrote: “You didn’t have time to think of who was up in the air or what was going on. We were just putting plots on.”

Opportunities to eat or drink were limited and obviously forbidden during a raid with plots on the table, while toilet breaks were discouraged. Teller Hazel Gregory wrote: “Every day was different, which was difficult. It took no notice of the fact that the body clock never got accustomed to anything. Your eating, your sleeping was a different time every day.” The women were on their feet for the full shift and, according to Pickard, constantly interpreting the information coming in from radar, other airfields, the observer corps, spotter aircraft and from the headquarters of Fighter Command at Bentley Priory in Stanmore. “There was usually only 20 minutes warning of a raid and to scramble the aircraft from the nearest airfield,” he adds. Any errors could be fatal. And errors did occur, “but once Dowding improved coordination between spotters, airfields and the various operations rooms, by the end of the battle these had been reduced from about 40 per cent to 10 per cent,” Pickard explains. The Dowding System, as it became known, was, for its time and in those analogue days, very sophisticated.

“The women were from diverse backgrounds and educations and from all over the country,” says Pickard. “What mattered was their aptitude for the task. A bank clerk might be working next to a novelist who was working next to a postal worker. They were selected for their intelligence and ability to work under pressure.”

Every day was different, which was difficult. It took no notice of the fact that the body clock never got accustomed to anything. Your eating, your sleeping was a different time every day

The selection process took place at stations such as RAF Morecombe in Lancashire – quickness of thought, intellect and how articulate the candidate was were key attributes.

“The women were then invited to apply for the position of clerk, special duties,” explains Rachael Abbiss, the bunker’s principal curator of military history. “It was a deliberately nondescript job title for security purposes, but if accepted they could find themselves at the main operations room at Uxbridge or at the individual operations rooms at RAF airfields.”

The eponymous 1969 movie Battle of Britain has a mockup of the Uxbridge bunker. You can see it from 35 minutes in, and at other points in the film. Women on the operations room floor are milling around, talking calmly, and constantly confirming aircraft positions and numbers, while being watched over by top brass through glass windows around and above the room, one of whom is Keith Park played by Trevor Howard. In what is probably cinematic licence, when a roof partially collapses under a German bombing raid at one of the airfield operations rooms, the women don their helmets and calmness prevails. But as a general example of the stoical attitudes abundant through the summer of 1940, it probably has merit.

In the film, Susannah York plays section officer Maggie Harvey whose fighter pilot husband, played by Christopher Plummer, is demanding she changes her job to be nearer his squadron. He objects to her arguments that her role is as vital to the war effort as his and accuses her of being “a parade-ground suffragette”. Obviously it’s fictional but as a metaphor for the attitudes of the day, and the prejudices the women of the operations room might have faced, it is probably accurate.

The Uxbridge woman were billeted close by, says Abbiss. “They were often housed in the married quarters of RAF Uxbridge, four to a room, or sometimes at digs locally or in pubs. Many of them socialised in the dance halls of Uxbridge or nearby Hillingdon, or they took a trip into London to see a show. But much of their time was spent working in the bunker or sleeping.

“And it wasn’t only in the operations room where women were playing a major role,” she adds. “Women of the Air Transport Auxiliary flew aircraft to various destinations around the country where they were needed. It was dangerous work – these were new aircraft with little training and no manuals. They had no protection, weaponry and no radio.” Some of them became expert fliers. Wing commander Guy Gibson – of Dambusters fame – and his colleagues were having difficulty flying and especially landing the RAF’s new Bristol Beaufighter. “The plane was known as the ‘suicide ship’ by pilots, it was very difficult to control,” Pickard says. “Gibson used to tell the story of the first time a fellow pilot of his saw it execute a perfect landing. His colleague realised that, as the pilot climbed out, it was a woman.”

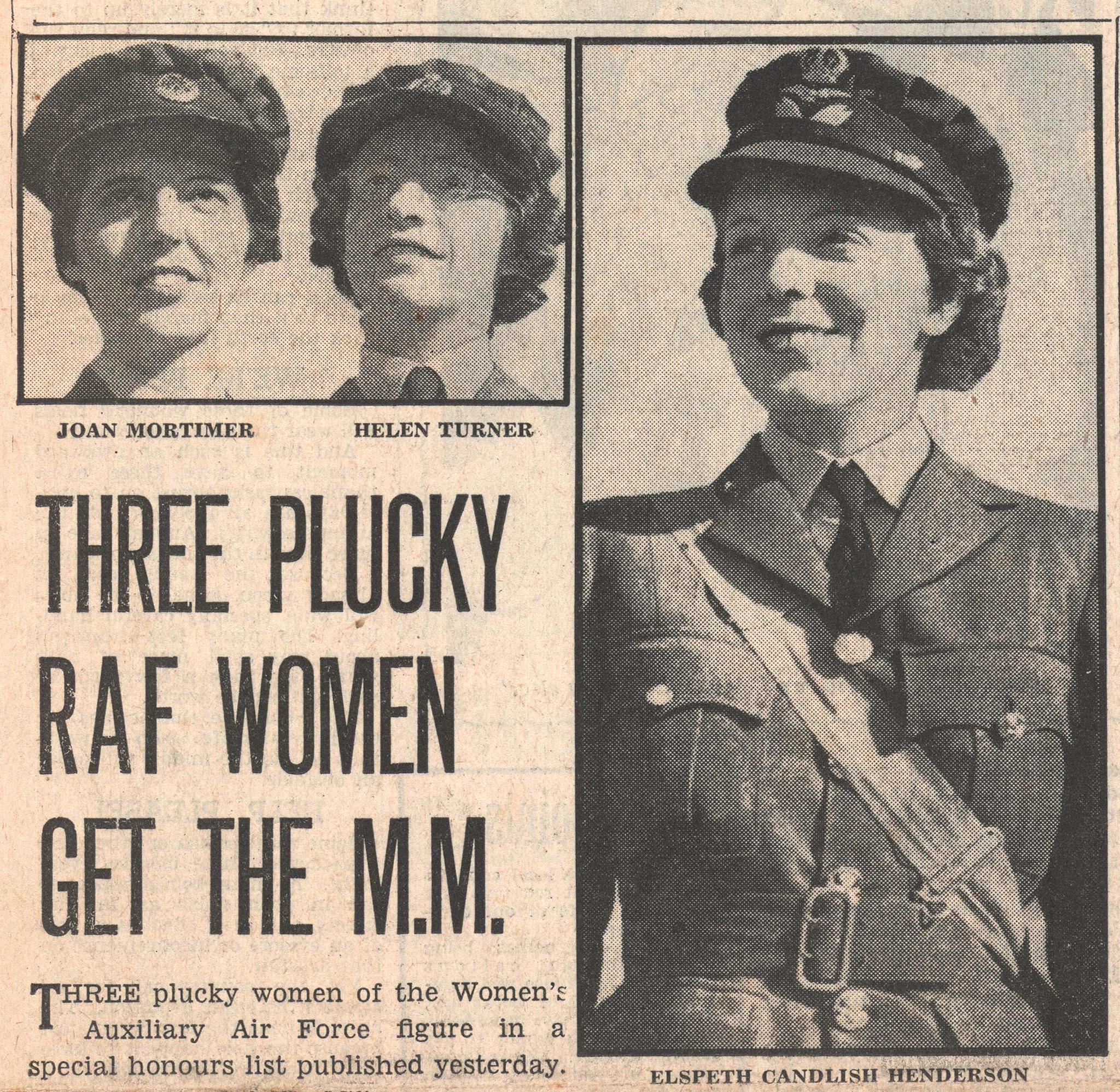

And women came under enemy fire for one of the first times during the Battle of Britain. “Three women at Biggin Hill came under direct fire as the airfield was being bombed,” relates Abbiss. “Their operations room was attacked but they stayed at their posts despite it being hit. Later Sergeant Joan Mortimer went out onto the airfield to mark the positions of unexploded bombs while the Luftwaffe continued their attack. All three won the Military Medal.” It’s possible that the attack on the airfield operations room in the movie is intended to depict this as women are struck by debris from the falling roof.

The course of the battle is now one of the most documented in military history. From July but especially after 13 August – designated “Eagle Day” by the Luftwaffe – and on through into September an all-out German assault on RAF airfields, aircraft and radar sites led to the RAF becoming severely stretched and under immense strain. The images the 1969 movie showing battle-weary but determined airmen sitting outside their huts throughout the summer, barely able to grab food before being scrambled into action again was an accurate picture as the pilots of 11 Group – overseen by the women of RAF Uxbridge – engaged the enemy over the counties of southern England.

The outcome remained in the balance. On 31 August the RAF suffered its heaviest losses of the battle. But then the Germans made what is now understood to be a huge tactical error. German führer Adolf Hitler and supreme commander of the Luftwaffe Hermann Göring had promised their people that the RAF was incapable of bombing German cities thanks to German air superiority. But in late August, in retaliation for lost German planes dumping their bombs on London, Churchill ordered the bombing of Berlin. Hitler, already dissatisfied with the progress of the campaign, was furious. He ordered that the focus of the Luftwaffe’s assaults should shift to bombing British cities in retaliation, hoping to draw the RAF out into a battle of attrition. What became known as the Blitz started on 7 September just as the Battle of Britain was reaching its crunch point on the 15th. There was sustained fighting thought the day with the RAF having to put up a stout defence.

Perhaps their most significant contribution was to the nascent stirrings of female emancipation and the changing of once chauvinistic opinion

Ironically on that day, Churchill chose to visit Uxbridge. At one point, all the lights on the indicator boards in the bunker were red. The tellers and plotters were working at full capacity. Churchill asked what reserves were available as wave after wave of German aircraft crossed the Channel. “None,” replied Park. “Red lights mean all are in the air, there are no reserves at all.” But 15 September was a turning point and despite London and other cities paying a huge price in civilian life and infrastructure, and despite the RAF being constantly stretched, changing the focus to bombing civilian targets meant the RAF and especially Fighter Command could regroup. The respite from bombing airfields and other targets meant the RAF could repair its aircraft, train more pilots and rebuild its airfields. Crucially it also brought the German aircraft over London into range of the RAF’s 12 Group fighters too. It was a tactical error to rank up there with Napoleon’s assault on Russia in 1812 or the Gallipoli campaign in the First World War. “It cost them the Battle of Britain, and arguably the war,” says Pickard, whose mother lived through the London Blitz.

The Luftwaffe had failed to destroy the RAF and although the battle officially continued until 31 October – with German aircrew casualties outweighing British by more than three to one – the summer weather had faded. No army would choose to invade as winter approached. Operation Sea Lion had been cancelled.

The women of RAF Uxbridge would stay on the floor of the operations room until victory in Europe was achieved. Eventually, the room became more of a communications hub as the Cold War began until the bunker was finally closed in 1958 as changing technology made it obsolete. And because the women were sworn to secrecy very few people were aware of the role they played in one of the greatest defensive actions in military history. Evelyn Fryer, a plotter from Stockwell, said: “We were part of it, we did our bit. But it was kept as secret as possible.”

And beyond helping to save their nation from the tyranny that had assailed Europe perhaps their most significant contribution was to the nascent stirrings of female emancipation and the changing of once chauvinistic opinion. Keith Park told the women who worked for the RAF that they had shown valour in abundance. It was an admission from the man who probably did more than most of his contemporaries to see off the German assault in 1940 that his concerns had been misplaced. Later, Lord Tedder, chief of the air staff would say this of Park: “If any one man won the Battle of Britain, he did.” Yet Park, who himself never received widespread acclaim, would doubtless be the first person to point to the contribution of the unsung women he was once so unsure about.

After an earlier visit to Uxbridge in August, Churchill climbed into his car at the door of the bunker and uttered words similar to his famous line regarding the personnel of the RAF. “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed, by so many, to so few.” His companion that day, major general Hastings Ismay, told him that the words would make a fine conclusion to a speech, advice Churchill followed on 20 August. And while it has oft been interpreted as a paean to the pilots fighting the Luftwaffe, it also applies in full to the woman of RAF Uxbridge and the vital part they played in ensuring the Battle of Britain was not another colossal military defeat.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments