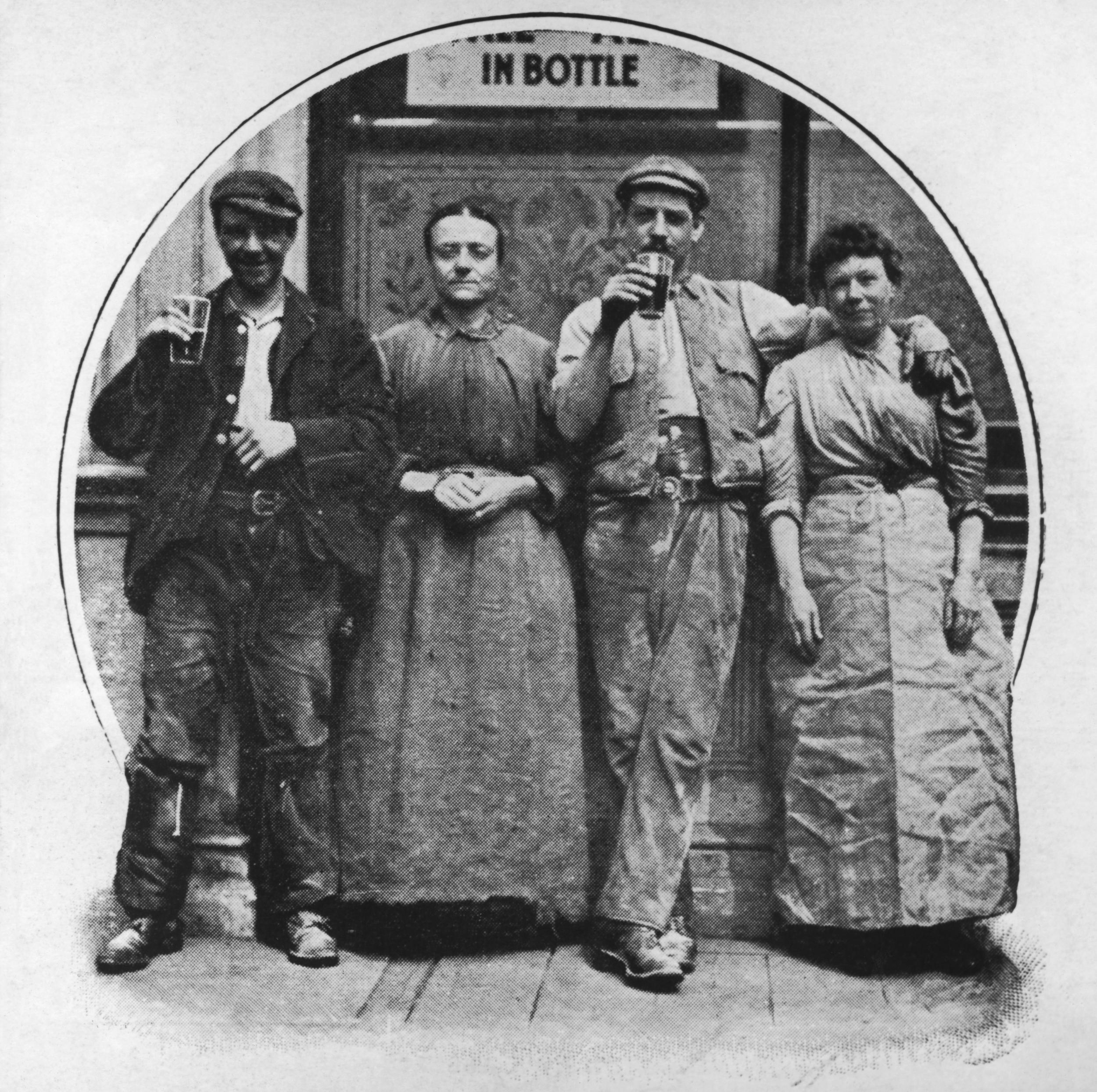

Time at the bar: Why are pubs disappearing from Britain’s streets?

They were once bastions of cultural heritage, but their numbers have been dwindling for years, with small independents bearing the brunt of changing drinking habits. Mick O’Hare looks back at the history of the Great British Pub and finds not all hope is lost

We’re going down the pub,” sang London punk band Sham 69 in 1978, and back in the Seventies they had plenty of watering holes to choose from: about 75,000 throughout the UK.

Today their drinking options would be more limited. The decline of the “Great British Pub” has been well documented and arguments over the hows, the whys and the wherefores have raged for years. There’s no escaping the fact that at one stage five years ago 25 pubs a week were shutting their doors permanently.

But is there a chink of light piercing the gloomy interior of the boarded-up hostelry? In August, the Greater London Authority (GLA) released data from its annual pub audit. And guess what? Figures for pub numbers in London had stabilised – nay, even shown a small increase. Pull those pints and order a double chaser!

Before we get carried out at closing time, however, let’s recap what the many competing theories have to say about the reasons behind the long-term reduction. If it’s true that in Shakespeare’s day there was a pub or tavern for every 200 Britons, by 1980 we had already travelled a long way from that state of conviviality. Nonetheless, even four decades ago, Britain had more than 60,000 pubs. Today, the figure is around 40,000, and the decline continues: it was estimated earlier this year that two pubs were closing every day.

Yet still, they play a prominent part in British social life, with research at Oxford University showing that they improve wellbeing and life satisfaction in those who visit them regularly. Even now, visiting a pub is one of the most important things on an overseas tourist’s bucket list.

So why the decline? Top of the list of culprits is the rise in home consumption of alcohol – it’s much cheaper in the supermarket, as we all know – and the phenomenal increase of other forms of gastronomic leisure, from cheap pizza chains to coffee emporia and sushi bars, all of which draw people out of traditional pubs.

“The sheer growth in the eating-out market over recent years means there’s massive competition,” says John Longden, chief executive of Pub is the Hub, the organisation that supports licensees across the country.

The change in dining habits is also matched by a change in drinking habits. Wine has increasingly replaced beer as the tipple of choice in the UK. Pubs are associated with beer drinking, restaurants are not – and not only that, tax on beer has risen disproportionally more over the past 10 years thanks to government policy.

Some pub-owning companies decided, on balance, that more money could be made from redevelopment and the land on which the pub was built. In many cases, they took advantage of laws favourable to them that led to pubs being converted into restaurants or convenience stores, even offices or homes. “When the owner of the pub I worked in changed, it was clear they had no interest in the business,” says Alan Smithies, who worked in a corner pub in northwest London. “It had closed within a year and it’s now a private home.”

Two other factors have affected the pub’s traditional role as a community space. The smoking ban in public places had a big impact – smokers will now buy their drink to consume at home – and young people are not following their parents into the rituals of drinking, many of them staying teetotal for health or cultural reasons, among others. More than a quarter of 18- to 25-year-olds don’t drink. And don’t discount the draw of Netflix and 24-hour sport, both better watched at home with a drink to hand.

Samuel Johnson’s quote about there being ‘nothing which has yet been contrived by man, by which so much happiness is produced as by a good tavern’ would ring rather hollow from the top deck of the 77 bus

The Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), in its report into the decline of the pub, pointed to taxation and the smoking ban (along with declining wages in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008 and subsequent government austerity programmes) as the two key drivers of pub closures. These had far more effect, its author Christopher Snowdon suggested, than pubs being converted into other property uses by pub-owning companies.

Between 1980 and 2014, the IEA reckoned Britain lost about 21,000 pubs, most of those in the years after 2006. And, despite a recent rise in fashionable or craft beer culture, with new breweries offering ever more exotic styles, pubs are selling half the volume of beer they sold 15 years ago.

But has London really bucked the trend? Geoff Strawbridge, Greater London regional director for the Campaign for Real Ale (Camra), says: “I’d be wary of taking the GLA’s figures uncritically. If the rate of pub closures has halted, it may be because in parts of London there are now so few left to close, and any apparent gain in openings in up-and-coming areas of London is down to bars that can never replace the heritage of the traditional pubs we have lost.”

Strawbridge points to Camra’s definition of a pub: among other stipulations, it should be open to, and welcome, the general public without requiring membership or charging for admission, serve at least one draught beer or cider, and allow drinking without purchasing food, with drinks being bought from a bar rather than relying solely on table service.

It’s not necessarily an exhaustive or scientific survey, but get on a random bus in Strawbridge’s domain of south London and take a ride.

The 77, for example, runs through some of the communities that have formed the backbone of the capital south of the river for generations. Its route starts at Tooting, where the Prince of Wales, Summerstown, is now a branch of Tesco – and in a journey of about an hour to Waterloo, in the centre of London, passes through Clapham, down Lavender Hill and along Wandsworth Road from Battersea to Vauxhall. You’ll pass quite a few traditional pubs on the high streets and corners – or what once were traditional pubs – and, as an aside, the Plough Brewery, although that shut its doors in 1924.

Very few still operate as public houses: many are boarded up, some are restaurants or esoteric clubs, others private houses or offices.

For pub aficionados, it’s all rather depressing – Samuel Johnson’s quote about there being “nothing which has yet been contrived by man, by which so much happiness is produced as by a good tavern” would ring rather hollow from the top deck of the 77. Of the taverns that are still extant, there are a couple about which you might think twice before crossing the threshold. Not so much hale and hearty as grim and glowering. But all these observations are taken through the windows of a bus. Like we said, not necessarily an evidence-based survey.

Nonetheless, considering the damage wrought on pub numbers over the past four decades, the news that, for whatever reason and however the figures have been calculated, the decline has slowed or been reversed must be considered good news.

The GLA’s survey said that the number of pubs in London in 2018 remained stable after falling by a quarter since 2001, with the capital now hosting 3,540 pubs, a small rise on 2018. Additionally, 11 boroughs saw an increase in pub numbers for the first time in years.

Perhaps crucially, after years of decreasing numbers in what is a low-paid industry, employment in the trade remained unchanged in 2018. Bigger pubs fared better than smaller sidestreet ones and London now has more big pubs (employing more than 10 people) than it had in 2001. But are these really community pubs, or even pubs that Sham 69 would recognise as such? Well, maybe some.

The GLA survey’s definition of a pub includes modern craft-beer outlets, music venues, bars, tourist pubs and gastropubs, among many others. The two definitions – Camra’s and the GLA’s – definitely overlap but don’t necessarily always interlock.

On the other hand, the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has insisted that traditional pubs, as well as any new openings, have a major cultural role to play in London life – and 74 per cent of Londoners agree with him. He has put in place measures to support the trade, including tougher planning rules for change of use, asking local authorities to recognise the value of their traditional pub heritage, protecting beer gardens from redevelopment, fighting business-rate increases and increasing support for at-risk pubs that are considered community hubs.

Other schemes such as a local authority declaring a pub an Asset of Community Value, or ACV, have been tried before but have met with very limited success.

It’s an unavoidable fact that society has changed. We are going to the pub less than we used to. And some of the reasons are positive. We live in better housing and consume less alcohol because of health concerns

However, Khan’s initiative also encourages local authorities to grant planning permission for new pubs to stimulate high-street regeneration.

So, is it all working? Khan says: “I’m encouraged by these results, but with pressure from rates, rent and development, it’s crucial the government and local authorities give them their full support too.”

Des de Moor, beer writer and the author of London’s Best Beer, Pubs and Bars, is in qualified agreement with Khan. “As with so many things like this,” he says, “it depends how you count. But I wouldn’t be entirely surprised if numbers had stabilised. Geoff Strawbridge makes a valuable point about there being no pubs left to shut in some areas, but I’m something of a Camra heretic when it comes to pub closures. The discussion is often tied up with nostalgic and romanticised ideas of what a pub should be. Pubs have to adapt to changing social trends, and always have done.”

Ironically, social changes might be another factor behind the stabilisation in pub numbers. The rise of new breweries run by the young entrepreneurs of the “craft beer” scene have also helped to increase the number of new pub openings, with their breweries – frequently crowdfunded by beer aficionados – often doubling up as bars in the trendier areas of the capital.

In fact, the UK now has more than 2,000 breweries for the first time since the 1930s. “They have proved that good beer need not be sold in traditional pubs,” points out De Moor. “And now micropubs and microbrewery taprooms serve the beer that was once only found in a traditional boozer.” He also notes that they are cheaper to run than older public houses often located in Victorian or Edwardian streets.

The rise of these new establishments is offsetting the loss of older pubs – and, although new brewery openings are now trailing off, De Moor suggests that “maybe the London beer/pub market is reaching a new equilibrium. Certainly I don’t get any sense of sweeping closures any more between subsequent editions of my guide. Venues from the previous edition which won’t appear in the next one have largely been left out because there are better recommendations and we have limited room.”

London Drinker, the printed voice of Camra in the capital, concurs with De Moor and Strawbridge that while traditional pubs may still be closing, they are being replaced with different drinking establishments that some old-school drinkers might not call pubs. Its October/November 2019 edition points out that “the GLA’s figures are, of course, net. This means they hide the point that we are still losing around 100 traditional pubs a year and they are being replaced by brewery taps, micropubs and new developments. We are certainly not getting ‘like for like’.”

As Camra’s Greater London regional secretary, Roy Tunstall, told the BBC: “While we welcome new bars, we deplore the loss of the traditional pub.”

Tony Hedger, in the same London Drinker piece, also notes the converse trend of pubs that had been converted to restaurants becoming pubs again. “Two examples of this are the Waterman’s Arms in Barnes and the Steam Packet in Kew, a former Cafe Rouge,” he notes. And old pubs are rising once more from the ashes. The Great Southern, next to Gipsy Hill railway station in south London, has reopened. It has a modern makeover, but is recognisably what is still known as “a local”.

“Launching a new pub is an exciting opportunity for us. We want The Great Southern to be a hub and meeting place,” says Don O’Rourke of the newly revamped pub, clearly intent on reinventing the community boozer.

Of course, nothing stands still. As De Moor points out: “It’s an unavoidable fact that society has changed. We are going to the pub less than we used to. And some of the reasons are positive. We live in better housing and consume less alcohol because of health concerns.”

Daniel Lucas, of the Jerusalem Tavern in Clerkenwell, told The Daily Telegraph that “the younger generation like to keep themselves fit. There are not as many people who drink at lunchtime.” Remarkably, students are now the least likely of all Londoners to visit a pub. Things certainly have changed.

This is also borne out by the loss of small neighbourhood pubs while bigger destination pubs for a special night out are surviving.

The great heritage pubs of London – such as the Cittie of Yorke in Holborn, the French House in Soho and the London Apprentice in Isleworth – still thrive, and three-quarters of Londoners (even teetotallers) believe such historical venues are an important part of the capital’s cultural heritage. Hence, perhaps, their longevity. “I once revisited the 12 ‘best pubs in London’ that had appeared in a 1967 guide,” says De Moor. “Ten were still open, and only one of the losses had been down to the stereotype of greedy developers cashing in on the property value of their pub.”

“Meanwhile, the smaller pubs that have survived have usually reinvented themselves by offering great food or a wide selection of beers and drinks. This will have helped stabilise the figures for London.

Maybe the hints of a revival are not solely a London thing. David Brazier, regional director for Camra in the northeast of England, points out that while statistics show that the rate of pub closures in his region is the lowest, he shares Strawbridge’s concern that “this is mainly because the northeast lost most of its pubs in the 1970s and 1980s”.

However, Brazier adds: “The northeast has more breweries per head of population than London and there are more pubs selling real ale than a few years back.” Maybe the uptick in London is not just an outlier – it could be part of a wider trend.

So, what of the future? Are we seeing off the long-term decline of the British pub, a model for conviviality – lest it be forgotten – that is copied around the world in the numerous pastiches of “British pubs” in cities from Barcelona to Washington DC.

“We will have to wait and see,” says De Moor. “You can’t predict long-term trends with any certainty. But brewing changes rapidly. Who could have predicted that in 2011 there would be 14 commercial breweries in London, and 70 in 2015? This is probably unsustainable because I don’t know many that brew every day. And some people have dismissed Britain’s brewery boom as a passing fashion driven by young ‘hipsters’ who will lose interest. We may see some consolidation because of overcapacity, but there is certainly a new demand for beer of good quality, which will still drive people to pubs and bars.”

Alan Smithies now works in a central London brewery taproom. “We are full every night,” he says. “Friday nights after work are manic. So I traded a job in a pub the owner didn’t care about, for one in which the owners have invested all their passion. That’s a lot of the difference and maybe it’s why new businesses are thriving. You just need that passion. It’s a shame the owners of my previous pub couldn’t see that.”

Of course, the British have long worried about the decline of their pub heritage.

As far back as the 1930s, researchers from Mass Observation, the now-defunct social research organisation, noted that “the pub as a cultural institution is at present declining” and, in 1973, Christopher Hutt wrote The Death of the English Pub. But there is no doubt that the decline in pub numbers, especially this century, has been genuinely extraordinary, and it wasn’t mere hyperbole or exaggeration that led some to believe this great institution was on its way out.

That London might have bucked the trend, in whatever form, is surely means for an extra half (if not a full pint) this weekend.

As Tom Stainer, Camra’s chief executive, commented earlier this year: “We know that pubs across the UK, and especially in London, have been struggling. Stability is absolutely what beer and pubs in London need right now. We look forward to working more with the mayor’s office to highlight the amazing economic and social value of the capital’s pubs and the vital role pubs have to play in London.”

Which is a more modern, diplomatic and business-speak way of saying what Hilaire Belloc was telling us in 1912: “When you have lost your inns, drown your empty selves, for you will have lost the last of England.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments