Child sex abuse, corruption and cover-ups: How football can and must move on from its darkest time

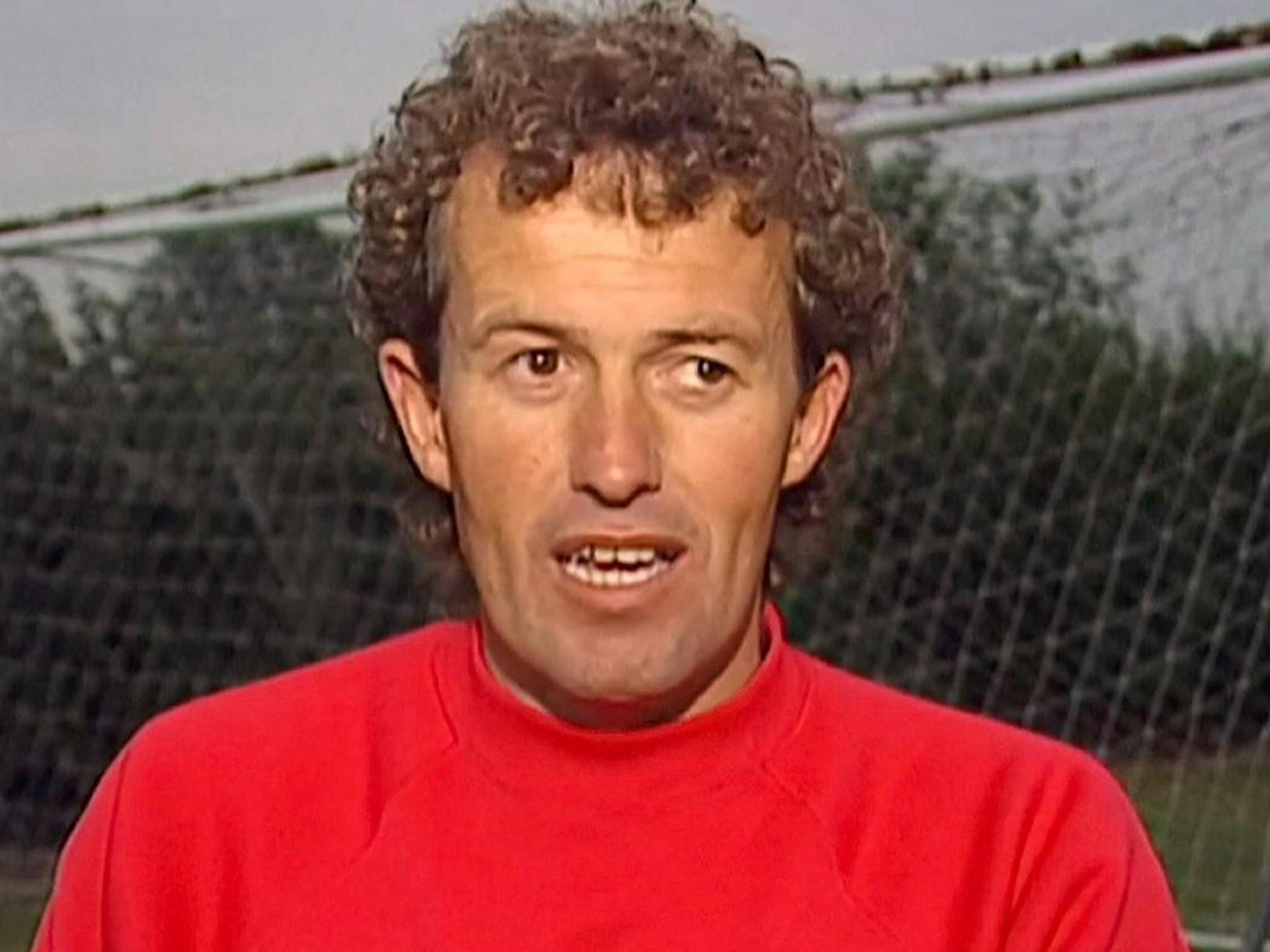

Ahead of the results from an inquiry into the allegations, Andrew Woodward and Steve Walters, two of the first victims to name Barry Bennell as their abuser, speak to Harriet Marsden about life after the revelations

Andrew Woodward has no idea how many times he was raped as a child. In November 2016, the ex-footballer waived his right to anonymity and revealed that he had been a victim of sexual abuse for more than six years in the 1980s. The one-time Crewe Alexandra defender named his former coach, a convicted paedophile who police would later say had “almost an insatiable appetite” for young boys: Barry Bennell. Bennell has been described as the most persistent paedophile in Britain’s history. He was also Woodward’s brother-in-law.

Soon after, his former Crewe teammate Steve Walters also came forward as a victim of Bennell. Then Manchester City’s David White, then Paul Stewart. Then another, and another. A second coach, Frank Roper, was accused. Then George Ormond. Then chief scout for Chelsea Eddie Heath. Bob Higgins. Hugh Stevenson. Jim McCafferty. Paul McCann. Week after week, the list grew longer.

Thousands of people came forward. Referees, coaches, scouts, managers and staff from 340 different clubs, both amateur and professional, were all implicated. It was like an unblocked pipe: a deluge of accusations painting a picture of systemic sexual abuse and cover-ups. Many victims alleged that clubs had known – and ignored it.

British football was shaken to its core. There were so many accusations that the Football Association quickly commissioned an inquiry, led by Clive Sheldon QC, to find out who knew what. The FA chairman, Greg Clarke, called it “the biggest crisis in the history of sport”.

Woodward was hailed as the hero: a proto-#MeToo whistleblower who broke the cycle of stigma, shame and silence. Last summer he published Position of Trust: A Football Dream Betrayed to mass acclaim: an account of the abuse and a damning indictment of institutionalised corruption and failure to protect the vulnerable. Hundreds of people credit him with finding the strength to come forward about their own abuse. But now more than three years later, Woodward tells The Independent: “There are times when I wish I’d not done it.”

Woodward has battled with alcoholism, depression, post-traumatic stress and suicidal thoughts. “And as much as I’ve helped so many people, and I’ve written my book to help people, it’s been an absolute nightmare. I’ve been through hell and back.”

He has also been the victim of extensive online abuse and trolling. Just days after his interview, an 18-year-old in Crewe created a fake Twitter account pretending to be Bennell. Lewis Hawkins and his father both used it to subject Woodward to a barrage of abusive messages. The following year, they were both imprisoned for 12 months. “It’s had a huge effect on so many things within my life,” he says. “I’ve been targeted, relationships have broken down, oh god, I can’t even put it into words the effect it’s had on my mental health, it’s had an effect on everything in my life.”

His voice breaks: “I’ve kept it really quiet but it’s really affected me.”

As of January 2020, Bennell’s victims are still waiting on the results of the inquiry, thanks to legal complexities as the CPS prepares further charges against the imprisoned paedophile – who is still attempting to contact Woodward from behind bars. Woodward, now 46, says: “I want to get across that I’m a human being – I’ve done the right thing, but I have had to suffer for it, hugely.”

A child’s dream

Woodward began his football career for a youth team in Stockport, where he was born in 1973. He soon caught the eye of a charismatic youth coach and scout, Barry Bennell. Known for spotting future talent in young boys, Bennell was well-liked and trusted by families and colleagues. He worked for Crewe and was associated with Stoke City and Manchester City as well as various youth teams. He was also a serial sex abuser and paedophile.

Bennell brought Woodward into Crewe’s youth team, which had a reputation for nurturing young players. He became everything to the boy: coach, hero, friend. Woodward would regularly stay over at his house in the Peak District.

“It was like a treasure trove, a child’s dream,” Woodward told The Guardian’s Daniel Taylor, echoing Michael Jackson’s Neverland. “When you walked through the door there were three fruit machines. He had a pool table. There was a little monkey upstairs in a cage who would sit on your shoulder … It was my dream, remember, to be a footballer and it was like he was dropping little sweets towards me.”

Then, when Woodward was 11, the abuse began. It would alternate between physical attacks and emotional manipulation. Bennell preyed on “softer, weaker” boys, Woodward said, threatening them, spoiling them, raping them. Woodward’s nightmare would continue for six and a half years. And everybody around him, Woodward says, knew. Other boys would mock him in the changing room. He says that Dario Gradi, then the Crewe manager, walked in on him with Bennell. “They used to argue over whether I was staying at his house or Bennell’s house.”

Because he [Bennell] produced the goods, because he was a good talent-spotter, a blind eye was turned by clubs. They were more interested in the talent. That’s the ruthless edge of football. That helped him get away with it

Woodward began to deteriorate mentally, while Bennell’s power over him increased. When Woodward was just 14, Bennell began a relationship with his 16-year-old sister, later marrying her in 1991. It was like torture, Woodward says, sitting at the table for Sunday lunch and watching them laugh with his parents. “He had control of the whole family,” he says, “and [speaking out] has had a huge effect on my family. It’s had a huge effect on her, and on our relationship.”

Charlie Webster, athlete, presenter and anti-abuse campaigner, tells The Independent that this is typical behaviour. “The thing about sexual abusers is that they don’t only groom the victim – they groom the family, and they groom society. My coach groomed my mum as well.”

Webster, now 37, revealed in 2014 that she had been abused by her running coach when she was 15. Like Woodward, she waived her right to anonymity to talk about the man who was later sentenced to 10 years in jail. “Perpetrators rely on the family to say, ‘it must be your imagination, he’s such a nice guy’,” she says. “They psychologically manipulate anyone around the victim to make sure everybody’s silent. They make sure that the victim’s isolated.”

Woodward began to struggle with anxiety and injuries, even while playing professionally. As he told Taylor: “It was hard because us footballers are supposed to be butch and strong, aren’t we?”

Meanwhile, one of Bennell’s other victims reported him, and the police began investigating other allegations in Spain and the United States. In 1994, he was arrested in Florida on a football tour after a 13-year-old player accused him of rape. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment. After his arrest, four players came forward to the British police. So even though he did not serve his full time in the States, he was arrested when he returned to England.

In 1997, Channel 4’s Dispatches aired a programme about child abuse involving Bennell and two other coaches. The documentary, “Foul Play”, featured journalist Deborah Davies asking Charles Hughes, then the FA’s director of coaching, whether the organisation should establish rules to protect children from abuse. She was ignored.

Only one of Bennell’s victims in the documentary gave evidence on the record: Ian Ackley. He, too, was an amateur youth player all those years ago. Almost 20 years before Woodward, he was telling the world about Bennell’s crimes. He, too, was ignored – and holds the FA as responsible, as well as Bennell.

“Because he [Bennell] produced the goods, because he was a good talent-spotter, a blind eye was turned by clubs. They were more interested in the talent. That’s the ruthless edge of football. That helped him get away with it.”

Everything was so impressive about him and he had this ability to make you feel special. He used to promise me he would make me a better player. He would tell me I was the best young midfield player he had ever seen, and that he would help me play for England, and I believed him

Ackley, who was abused until he was 14, later wrote about the blasé response to the documentary, citing one “particularly damning” review by a Telegraph journalist. “He wrote that he felt slightly sorry for the FA and that the programme was intimidating and unhelpfully scaremongering. I hope he’s revised his opinion now and followed events over the last year, when so many people found the courage to speak out about so many abusers at clubs all over Britain.”

In 1998, Bennell was charged with assault and buggery over nearly 30 years, against boys aged between nine and 15. He was found guilty of 23 offences against six boys – although another 22 offences were kept on file, to spare the young boys the trauma of a trial – and was jailed for nine years. Ackley was one of six people who testified.

Woodward, by then 24, was elated. He began to play some of his best football at Bury and Sheffield United. But one Sunday, he suffered a terrible panic attack which landed him in hospital – and another the next week. The traumatised young man began receiving treatment at the Priory, and soon stopped playing professionally altogether. He was only 29.

Woodward later became a police officer, but was dismissed after 12 years on the force for having an inappropriate relationship with the sister of a crime victim. “The only reason I joined the police was because I wanted to help people,” he says, “and it was the worst decision I ever made. Because I didn’t realise that I’d have to be dealing with paedophile cases.”

By 2015, Bennell was out, living in Milton Keynes under the name Richard Jones. The British police launched Operation Hydrant, which investigates historical child sex abuse, and by the end of the year it had identified more than 17 suspects from the sporting world, at 22 sports venues. Bennell was sent back to prison for another two years for sexually abusing another footballer, David Lean.

What have I done?

So why did Woodward speak out in November 2016? “I’d been through therapy, and they’d said that I needed to write it down,” he says. “Also my dad was dying from motor neuron disease. I needed to give my dad that relief that he wasn’t on his own. So at least before he died – and I put my whole life on the line because I could have been on my own, and if people hadn’t come out then I wouldn’t be here.”

In his book, he described how it felt to first see that article online. “I think Danny did a great job but, even so, my first reaction was: ‘Oh, fuck, what have I done?’”

But almost immediately, he says, his life changed. Victims began coming forward in their hundreds, phoning Woodward and the paper. “If nobody had come out then I was ready to go. It was life or death. But the fact that people did, I was able to allow my dad not to be on his own and also to give all the other people a chance to have a voice.”

One voice would become the most significant: his former Crewe teammate, Steve Walters. He read Woodward’s interview and phoned Taylor in tears to say that he, too, had been abused by Bennell. He had never revealed it before, even when the police questioned him.

Walters, born in 1972, grew up in Plymouth and was spotted by Bennell at Manchester United. Like Woodward, he was brought by Bennell to Crew and would often sleep at his house. “Everything was so impressive about him and he had this ability to make you feel special,” Walters said. “He used to promise me he would make me a better player. He would tell me I was the best young midfield player he had ever seen, and that he would help me play for England, and I believed him.”

Walters, too, remembered Bennell’s house like a “kids’ grotto”, and that Bennell would let the monkey “shit everywhere”, so he could force Walters to take his shirt off.

The young player was soon feted as a future star, even as his champion abused him in secret. He made his first team debut at 16: the youngest player in the club’s history. He still holds that record. But just a year later, he was diagnosed with a blood disorder and suffered from temporary arthritis. He was told that he might have caught the infection from Bennell. “That, for me, is one of the hardest things.”

Walters, like Woodward, began to deteriorate. He tells The Independent: “I did go totally off the rails, getting involved with drinking heavily, drugs, all caused by this.” He says that one of the reasons he came forward was that he wanted the supporters and the people of Crewe to know why he “went down that sort of avenue”, explaining: “I don’t really think I had much choice.”

Walters says that he, too, believes that Crewe had heard the rumours about Bennell’s reign of abuse. “That would be the way of life back then – it was everyone’s dirty secret, wasn’t it? Everyone knew what was going on, but chose to look the other way.” (Crewe declined to comment for this story.)

Walters and Woodward were reunited, bonded by their shared revelations. The two survivors, along with ex-Manchester City player Chris Unsworth and former teammate Jason Dunford, were interviewed on the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire show and blew the scandal wide open. More than 800 victims came forward that day.

To help cope with the onslaught, the men set up an organisation they called the Offside Trust, to support victims and campaign to keep children in sport safe. (Unsworth and Walters still run the trust, although Woodward has since left.) Unsworth, an ex-Manchester City player, was abused by Bennell from the age of nine. He thinks he has been raped between 50 and 100 times – but that nobody ever spoke about it.

Walters now says that the show is “quite unique”, and praises how supportive the team were after the interview aired. Just this week, Woodward, Walters and Unsworth wrote to the BBC director general, Tony Hall, to protest against the BBC scrapping the programme. They said that they chose to speak to Derbyshire because “we trusted her and her programme to help tell our story and aid our campaign for justice”.

In his book, Woodward recalls that a 13-year-old boy had contacted the show to say he had been a victim of sexual abuse. “He’d been sitting in a dark room that morning, suicide note written. Louisa [Compton, the show’s editor] asked if I’d be OK with being in direct contact with this person.”

The boy had been ready to take his own life, his parents upstairs unawares. “The lad had watched the interview and stopped himself,” he wrote. “We spoke later on. I told him how glad I was that he’d not gone through with what he’d been planning to do. We talked about what he could do now, about speaking to a doctor, to his parents. To the NSPCC if that was what he needed. ‘You’re not on your own, you know.’

That would be the way of life back then – it was everyone’s dirty secret, wasn’t it? Everyone knew what was going on, but chose to look the other way

“When I think about my own life, that conversation is maybe the single best thing that’s ever happened to me. I felt worthwhile, validated, as if I’d been able to do something that really mattered. A life had been saved.”

Devil incarnate

Bennell, by then 62, had already served nine years for sexual offences but was out of prison, on licence. But while he was behind bars, he had tried for years to contact Walters, Woodward and other young footballers he had abused. Walters tells me that Bennell would send him letters, sometimes asking for help. Just last week, Woodward received a Facebook friend request from a man calling himself Richard Barry. Woodward is sure it was Bennell. “When I saw it there, I was like, how dare you do that? He had pictures with people I know he was friends with, so yes, it was 100 per cent him. You couldn’t make it up, could you?”

By June 2017, Bennell had been charged with 55 counts of assault on four underage boys. In February 2018, he was jailed for 31 years. The judge called him the “devil incarnate”. Outside Liverpool Crown Court, Woodward, Unsworth, Walters and two other victims read statements about their abuse. The clubs expressed their sympathies, but reiterated that they had not known.

This wasn’t the full story. In fact, it seemed that when Bennell left Manchester City and joined Crewe, he had already been identified as a risk. Manchester City were warned by one of their own coaches about him. People started to ask questions about whether there was a coverup, or attempts to avoid bad publicity.

Hamilton Smith, a former managing director of Crewe and board member from 1986 to 1990, said that he had raised concerns about Bennell’s relationships with young players (Crewe denied it). Bennell was allowed to stay at the club – but not left alone with the boys. He was also forbidden from having sleepovers. Soon after, the BBC revealed that Gradi had received a letter in 1989 asking him to investigate Bennell.

All through 2019, revelation after revelation in court undermined Gradi’s claims of ignorance. Gradi admitted that he had not carried out proper background checks about Bennell – because, at the time, the FA had no guidance on child protection. He admitted to the sleepovers. He had not asked Manchester City, Bennell’s previous club, for a reference. He admitted he had sacked Bennell from Crewe in 1992 – but for failing to follow instructions about a pre-match coaching session. He did not explain what those were.

It emerged that Woodward had in fact sued Crewe for damages back in 2004 – unsuccessfully. “It was my opportunity to be anonymous,” he says, “to out the football club, and I did everything I could.

When I think about my own life, that conversation is maybe the single best thing that’s ever happened to me. I felt worthwhile, validated, as if I’d been able to do something that really mattered. A life had been saved

Most disturbingly, Woodward says he had to visit his abuser in Wymott prison, to ask Bennell to give him a statement. “That was horrendous. I went into child mode. Horrendous. I sat with him and his words to me were: I still love you. And I did that and I got in the car and I cried. But the reason behind it was I wanted to out that football club for what they did to me and so many others. They knew what was going on.”

A sickness in sport

Woodward and Walters both believe that their abuser was part of a cross-border paedophile ring, with particular connections to Scotland where he often took youth teams to tournaments. Just this month, the Scottish FA launched an investigation into the rumoured network of predators in youth football. One survivor claims he was abused by both Bennell and Jim McCafferty, a Celtic kitman and former boys’ club coach, after he was introduced to them by Bill Kelly, another former coach. “They were prolific, connected and worked together,” he said.

(McCafferty was jailed last year for molesting children over 24 years. Kelly was jailed for assaulting at least 12 players over 22 years. Kelly denies having any connection with McCafferty or Bennell.)

The Offside Trust believes that predatory youth coaches exchanged grooming tactics and shared victims. Techniques used by Bennell and Gordon Neely, who coached at clubs such as Hibernian FC and Rangers, seem eerily similar. Both paedophiles would terrorise the children with ghost stories and horror films before comforting them with hugs, and more.

(Neely was accused of rape after he died of cancer in 2014, aged 62. His club Ranger is accused of covering up the reasons for his departure.)

Woodward believes Bennell colluded for a long time with at least one other paedophile who has not been named. Bennell has also been connected with Roper, Bob Higgins and Kit Carson. They are all either dead or imprisoned on abuse charges.

Since Walters and Woodward came forward, the sheer scale of the sexual abuse in UK football started to emerge. People began to ask, was there some sickness in football? The nation’s favourite sport seemed like a pitch where power, money, trust, promises of stardom and traditional masculinity collided, creating a perfect storm for abuse to occur – and to go unreported.

Although many sports have their own stringent safeguarding in place, even now, there is no mandatory reporting law in the UK. If you witness sexual abuse of children at a football club, you are under no legal obligation to report it to the police.

Max Baines, a barrister at Red Lion Chambers who specialises in crime and sport, tells The Independent: “Sports governing bodies work together with local authorities to investigate and conduct risk assessments, and where there is considered to be a risk appropriate measures can be put in place. This process, which is becoming increasingly prevalent, at least in sports such as football, should in theory prevent a predatory coach who presents a risk at one club from simply moving to another club.” In theory.

A spokesman for the Offside Trust says that introducing mandatory reporting for suspicions of abuse “would be another vital tool in making the will of abusers to seek out new settings harder, the police, local authorities and governing bodies have a responsibility to ensure as far as possible the safety and wellbeing of all children”.

Sexual abuse in sport is, of course, not exclusive to football. Mike Hartill, author of Sexual Abuse in Youth Sport and senior lecturer at Edge Hill University, explains that football has more cases of abuse than other sports “simply by virtue of the number of people that participate in it”.

As Walters points out, sport is an easy way for a predator to get privileged access to children. Statistically, he claims, one in five men have inclinations towards young boys or young girls – and one in 14 act upon them. “Those figures are scary.”

According to Webster, “It’s really important to emphasise that sexual abuse is about positions of power, that’s why sport and coach relationship really lends itself to that, but it’s not exclusive to sport. I’ve been asked whether sport or football has a sexual abuse problem – it’s like, no, society has a problem with sexual abuse.”

Position of trust

The relationship between coach and young athlete lends itself to exploitation, says Woodward, not just because a predator has unfettered access to the child, but because he is the gateway to what the child wants more than anything else. “It’s not just the athlete – what it is is that desire to be an athlete, to be a professional footballer. It’s the ultimate boys’ dream to be that. And they can take it away like the click of a finger.”

And, like Woodward says with the title of his book, a coach is in a relatively unique position of trust with a child. The relationship is, by default, physical. The coach has access to the athlete’s body, and the places where they wash, or change their clothes. The coach functions outside normal time boundaries of school, and is often alone with a protégé.

I sat with him and his words to me were: I still love you. And I did that and I got in the car and I cried. But the reason behind it was I wanted to out that football club for what they did to me and so many others. They knew what was going on

Webster explains that the coach’s position of power “forms the fundamental basis of the grooming process which can start long before physical abuse”.

“When it happened to me, I completely trusted my coach, because I’d spent so much time with him before he’d even done anything physically to me, but little did I know that was part of the grooming process to get me in a position where you implicitly trust that person. It’s very, very confusing because this is somebody that I’ve known, that has my best interests.

“I wanted to be a good athlete, I wanted to win, I’m competitive, I wanted to be the best. And you believe them, not because you, the victim, are a fool, but because they’ve already groomed you for so long to believe everything that they say.

“I always say that the perpetrator puts their shame into the victim, and shame is such a powerful emotion that when you feel it, you feel bad, you feel like you’ve done wrong. And that gives the perpetrator the best cover ever, by shaming the victim, so the victim never says anything.”

“Position of trust” laws – or Section 21 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 – make it illegal for adults in certain roles to have sex with a child in their care under 18. This covers positions like teacher, carers and hospital workers. This does not cover sports coaches.

The Ministry of Justice recognises that this is a loophole and a problem, and has said in the past that it will expand the definition to include coaches. Because as it stands, a coach could groom an athlete until he or she turns 16, and then abuse them and claim it was consensual. Tracey Crouch, then the sports minister, proposed a law in 2017 to raise the age of consent to 18 when it comes to sports coaches, as it is for teachers, hospital workers and carers. This has not happened yet.

The Offside Trust responded: “We support the proposed law to make it illegal for sports coaches to have sexual relations with 16 and 17-year-olds in their care. This anomaly puts vulnerable people at risk of abuse. The Offside Trust is now working with the FA, clubs and other organisations on a range of safeguarding issues.”

Natalie Marrison, partner and head of personal injury and abuse law at Ramsdens Solicitors who helps families affected by child abuse, tells The Independent: “The extent of high-profile sports abuse scandals in recent years has highlighted the importance of safeguarding young men, women and children involved in sport from predators who occupy a position of trust.”

Marrison, who is also a trustee of the charity Parents Against Child Sexual Exploitation, says: “The Larry Nassar scandal last summer highlighted the prevalence of the problem in the US. During Nassar’s seven-day sentencing hearing, the name John Geddert was mentioned each day. Accusations have included young athletes as being deprived of water by Geddert and having strict weight restrictions imposed upon them.”

Webster, too, mentions the Nassar case. “When I read the testimony and statement from the US gymnasts, honest to god you could have put my name in there and replaced the perpetrator’s name – it was pretty much the same. And that’s shocking because I was a kid brought up in Sheffield, they were over in the US … and the commonality around sport and that coaching scenario is that they kind of manipulate and get into their head that without them, you’re nothing. And I think that’s what’s so powerful.”

90

cases against Bennell are still waiting for review

What next for English football?

In the summer of 2018, the Sheldon inquiry reported that after nearly two years of investigation it had found no evidence of institutional coverup in UK football, or of a paedophile ring. The full report was expected in September, but it was delayed due to Bennell’s pending retrial. The Offside Trust said it was “a huge disappointment”, and asked for an interim report. At the time of writing, no new date has been announced.

The inquiry has reviewed tens of thousands of documents and interviewed more than a hundred people, looking closely at Crewe, Manchester City, Aston Villa and Newcastle, as well as Chelsea given the scale of allegations against Heath, their chief scout and a long-time abuser.

An independent report into the Heath scandal found that Gradi, who was then Chelsea’s assistant manager and who has now been suspended by the FA, failed to report Heath despite a complaint that he assaulted a boy in the shower. Crewe, for its part, has abandoned plans for its own independent investigation. Taylor, the journalist who broke the story in the first place, tells The Independent that he believes the club has been “incredibly hard-faced about everything – to his knowledge they’ve never reached out to the victims … basically there appears to be no human touch there”.

Since the revelations, he says, Crewe seems to have “pulled the shutters down, and they’ve made it very clear that all they see that I’ve done by breaking the story is a bad thing. They’ve been openly hostile … it seems that they don’t see the bigger picture – all they appear to care about is their own image and reputation.”

Crewe let it be known that as the police had not charged anyone else, the matter was closed. But, says Taylor, the police are looking for criminal offences, whereas an independent inquiry looks for reasons why mistakes were made and how to prevent them in future. Abandoning the inquiry, in his view, was “a massive two fingers up at the victim and a lot of people took that really badly”.

He compares the situation to Chelsea, who “were big enough to say we did this wrong … but it seemed Crewe didn’t want to do that, so in my opinion, most reasonable people would consider that a pretty poor response”.

When Walters first came forward, he said: “I feel massively let down by Crewe … The club needs to get their heads out of the sand, make an apology and say something properly. It was Crewe Alexandra where it happened. It was the worst-kept secret in football.”

Crewe Alexandra declined to comment in relation to this story.

A spokesman from the FA tells The Independent: “The FA has commissioned an independent QC to conduct a review into what, if anything, the FA and clubs knew about the allegations of child sexual abuse at the relevant time, what action was taken or should have taken place. It is therefore inappropriate for the FA to comment on these questions whilst that review is ongoing.”

But the problem, says Taylor, is that the inquiry is not keeping victims up to date. “It’s like complete radio silence … their lives are completely on hold.”

Walters explains that there are about 90 people, himself included, still waiting to find out whether they will get criminal convictions against Bennell. “Can you imagine being brave enough to come forward then find out you’re not going to get a criminal conviction against your abuser? It must be the biggest kick in the teeth possible. So why would any other football survivors come forward now when they know for a fact that they’re not going to see justice?”

The worst part, he says, is not knowing when the report will come out. “It’s so difficult for all of us to try and carry on living our lives when we know that this FA inquiry is still ongoing. And I can’t imagine how difficult and how many football survivors there are, so it’s a huge task.”

The organisation has introduced a network of safeguarding officers and new policies around referrals and reporting concerns, as well as hiring people with experience in social work and child protection in sport. It also supports survivors with counselling via Sporting Chance, practical assistance via the FA Benevolent Fund and meetings with the FA chairman. The latest statistics, from March 2018, show that more than 2,800 incidents were referred to Operation Hydrant, and a total of 849 victims had come forward naming 300 suspects and 340 clubs – 77 of which are professional. Almost two years later, there are likely to be considerably more.

Male #MeToo?

Since November 2016, narratives around exploitation, grooming and sexual abuse have changed immeasurably, particularly after the #MeToo movement exploded in 2017. Woodward, who has been contacted by the #MeToo campaign, points out how much mental health and player welfare has been talked about, with Princes William and Harry both getting involved with the FA.

Walters, who has worked extensively with abuse survivors, says the #MeToo campaign is “very important”. “I know primarily it’s been women but obviously November 2016 when this broke out, we kind of paved the way for the male survivors to come forward, because if the majority of these male survivors who come forward now, they’ve seen that we’ve done it – being ex-footballers, a male macho sport, if we can do that live on television, it’s got to give strength to others to come out and speak, which is fantastic.”

Webster also sings the praises of #MeToo and its progress for gender equality. But, she says, “what’s really important is making sure that we understand abuse happens to men and boys and girls as well, and actually child sexual abuse is about power not gender”.

When the male footballers spoke out, she says, it was “so great to hear those voices, and to hear male voices talking about that … but then what changed after that?

“When we hear these big cases, and then nothing changes, and there’ll be another group that we hear about down the line. And then the media will have an uproar and then it goes away again and nothing changes. It shouldn’t be like that every time.”

She says that “once the media go away”, the sports governing bodies “don’t feel any pressure and they don’t do anything”.

Her words are eerily prescient. Just days later Taylor, now at football website The Athletic, published allegations against Phil Edwards, a former physiotherapist at Watford who allegedly abused more than 20 victims. “An investigation is now underway to establish whether he was allowed to get away with it because complaints were ‘brushed under the carpet’,” Taylor wrote. Most of the newspapers did not even follow it up.

Are things really different?

Walters is positive about progress, saying that at “all the premiership clubs and the majority of the championship clubs, the safeguarding has improved tenfold, obviously after what happened, it’s improved beyond recognition”.

“But,” he says, “as you work your way down the leagues, all the way to grassroots levels, there are still lots of issues, because obviously at the top they’ve got the ability to employ the appropriate people. There are still holes and cracks within the system, and that needs to change.”

There is still a long way to go, especially at grassroots levels, but children, parents, clubs and coaches now have a far greater awareness of safeguarding issues as a result of the high-profile convictions

It’s a safer world now, he says, but it’s still a scary one.

According to the Offside Trust: “The subsequent months and years have seen hundreds more survivors across all sports, not just football, bravely telling their own stories and pursuing justice. More than a hundred sports coaches have been convicted and there can be no doubt that youth sport is a very different environment in 2020. There is still a long way to go, especially at grassroots levels, but children, parents, clubs and coaches now have a far greater awareness of safeguarding issues as a result of the high-profile convictions.”

But when I ask Webster whether she thinks things are different now, she says: “No, and I will go on record to say that. I know it’s not. And I know cases right now where things are being covered up still. I know there are organisations within sport that are not doing what they should be doing and I know that for a fact. This is not something that’s historical.

“I feel like on the surface we like to say things have changed, but I think fundamentally they haven’t, because otherwise why would someone like Andy be getting abused? It’s absolutely disgusting.”

Unlike Woodward, Walters says he has suffered no online trolling or abuse since he came forward – but that “it has been tough”.

“There are times when you feel down yourself, and it’s hit me financially – I’ve got my own business, and it’s had a bit of a negative impact on that, because obviously there was the criminal process and the civil process as well, so it’s a lot to deal with in such a short amount of time.”

Webster says that if somebody asked her now whether they should report their abuse, she “wouldn’t be sure whether I would advise them to, because I know they would probably get some abuse on social media. I’m not entirely convinced that the authorities would support them, it’s awful to even say that but it’s true.”

She says that what people don’t understand, is that when survivors talk about the abuse they suffered, “it triggers exactly the same feelings you were made to feel by the perpetrator, like you were wrong or you were nothing, like you had no identity, your self-worth, you didn’t have any worth, you weren’t worthy of anything. It takes you back to that moment when you feel like you’re the one in the wrong, you’re worthless.”

However, Webster remembers that she got thousands of emails the morning after her revelations from people telling her their stories. “And that made it worthwhile for me, and I would do it again and again and again, if it helps people. I’m really pleased I did speak about it.”

It’s impossible to know how many other victims, and other predators, there are or have been. Gary Cliffe, former Manchester City youth player and long-time victim of Bennell, believes there will be hundreds more.

Walters says about 1,000 have come forward, and that he knows there are more. “We all know there’s still a lot of guys out there that are burying their dirty secret.”

I ask Woodward whether what he has suffered since coming forward might put someone else off telling their story. But he is adamant: “No, because each individual is different.”

Woodward has suffered abuse, in some form or another, for most of his life. But, he says, the positives make it all worth it. “I don’t think I’m ready yet to actually grasp what I’ve done because I’m still going through loads of trauma – I’ve not grasped what I’ve actually done. And people have said to me, do you realise what you’ve done? And I don’t, at the moment. But once I’m OK, I think I’ll get there.

“When I get messages from people and they say that you’ve saved my life … it’s when I get that that I feel cathartic for it, and I feel like I’ve done the right thing.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments