Baader-Meinhof: The glamorous and beguiling face of militant violence

The Baader-Meinhof gang bombed, kidnapped and assassinated its way across Europe throughout the early 1970s – with the support of many civilians and intellectuals. But what made this brand of terrorism acceptable – and chic? Mick O'Hare explains

Fifty years ago a 35-year-old journalist from Oldenburg in Saxony named Ulrike Meinhof authored a manifesto setting out the political aims and ideology of a group she had helped to establish. It demanded a left-wing revolution to overthrow the capitalist West German state and advocated a campaign of violence to achieve it.

The cover of the manifesto, entitled The Concept of the Urban Guerrilla, carried a red star alongside an image of a Heckler and Koch MP5 submachine gun. The logo had been commissioned by another member of Meinhof’s cohort, a 36-year-old man called Andreas Baader from Munich. Their organisation would become the Red Army Faction, better known – especially in the English-speaking world – as the Baader-Meinhof Gang. And they would go on to assassinate more than 30 people alongside a campaign of bombing, kidnapping and violent robbery.

The group rarely called itself Baader-Meinhof, preferring the German name Rote Armee Fraktion or RAF. They were a Fraktion, or fraction, because true to their Marxist-Leninist dogma they had no leaders as such, they were a single part of a greater revolutionary worldwide movement. However, the acronym RAF was always going to be confusing for English-speaking audiences and “fraction” rather than faction sounded erroneous, so Baader-Meinhof Gang (BMG) it was.

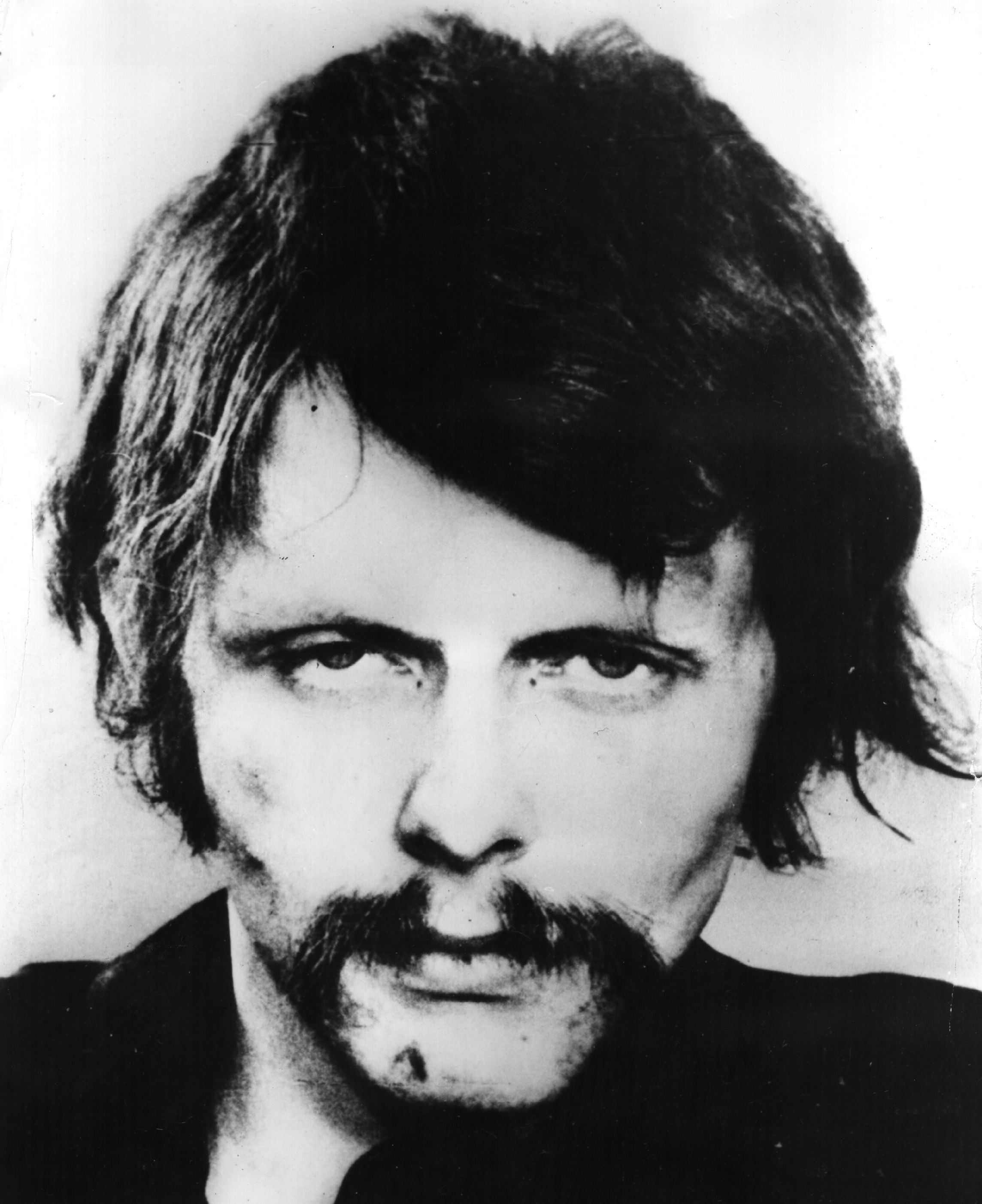

Many members, most with their roots in the West German student protests of the 1960s, such as Gudrun Ensslin, Jan-Carl Raspe and Holger Meins, had long been on the radar of the authorities as they progressed from university activism and street protest to rioting and arson. Indeed, Baader had first been arrested in Frankfurt in 1968 alongside Ensslin for burning shops in protest at the Vietnam War.

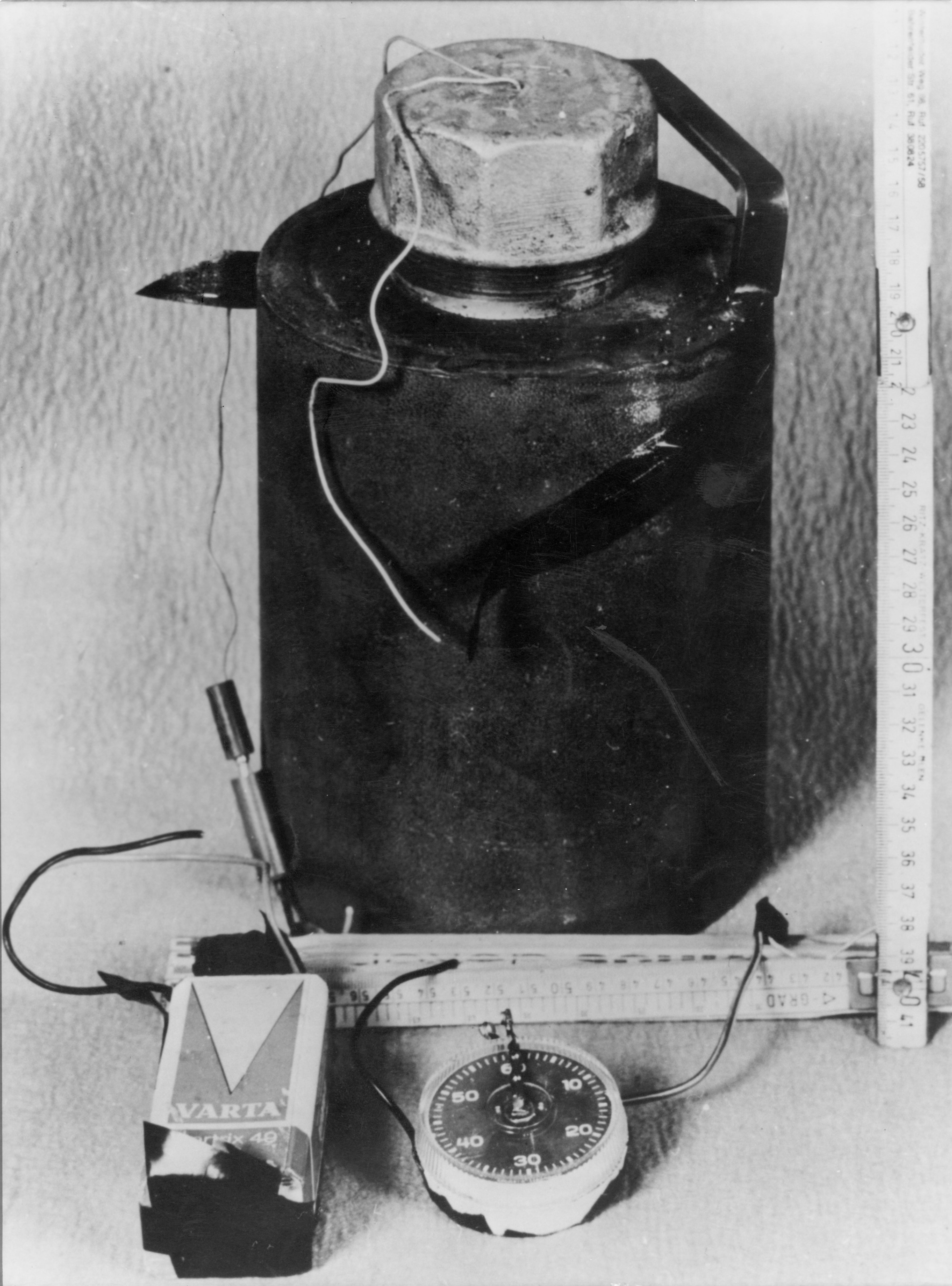

By 1971 BMG had moved on to murder, when police sergeant Norbert Schmid was shot as the group attempted to stop the arrest of member Margrit Schiller in Hamburg in October. But the gang unquestionably announced itself to the wider world when it bombed the US Army’s V Corps headquarters and its officers’ mess in Frankfurt on 11 May 1972 in protest at “United States imperialism and occupation”. Lieutenant Colonel Paul Bloomquist was killed in the explosion and BMG blasted itself into the consciousness of not just Germany but every western government.

And they continued to do so, driven by a belief that the ruling class of the post-Second World War West German state was merely a continuation of the Nazi regime that should have crumbled after its defeat in 1945. The same generation – including former Nazis such as Kurt Georg Kiesinger, who became Chancellor in 1966 – held the reins of power, BMG argued, and was at odds with Germany’s post-war youth driven by the latter’s opposition to capitalism, imperialism, racism, the US military presence in West Germany and more.

They wished to supplant the mores of the old guard with the new causes of the young. They also believed the media was controlled by conservative and US-driven forces, especially the tabloid newspapers run and owned by media mogul Axel Springer, publisher of the conservative daily Bild, who was a particular target of their ire.

Throughout the 1960s most industrialised democracies had faced the challenges brought about by the radical student movement. Characterised by street protests, rioting and striking, the list of flashpoints was long and varied: France in 1968, the civil rights protests in the US, and anti-Vietnam War dissent throughout the western world. It was from uprisings such as these that BMG took inspiration. The group believed it was part of a greater worldwide movement with threads running from the communist influence of Mao in China, the Cuban revolution in 1959, the long-running anti-Portuguese insurrection in Mozambique, the Palestine Liberation Organisation formed in 1964, and the guerrilla tactics of Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara all influencing their political outlook.

Seemingly with no irony considering the violence they begat, Meinhof wrote: “We are acting for those trying to free themselves from terror and violence.” Ensslin too had little compunction, her empathy for the cause bowing to its own contradictions when she stated: “Violence is the only way to answer violence.”

But while student movements around the world were rife throughout the late 1960s, in West Germany the historical legacy of Nazism threw the conflict into a starker reality. A whole generation was tainted by the rise and fall of Adolf Hitler and his subjugation and annihilation of entire races and cultures and they were determined to eradicate any link to that past.

Radical thought demanded no détente between the institutions of the West German state – which, in the eyes of the militant left and associated anarchist and libertarian streams of thought, had produced a post-war economic miracle without divesting itself of its pre-war past – and the socio-economic aims of the BMG. Where their parents had failed to resist the Third Reich, they were determined not to acquiesce again. “Dare to struggle; dare to win!” wrote Meinhof.

And so BMG bombed, kidnapped and assassinated its way across Germany and Europe throughout the early 1970s. The gang could sometimes simply capitalise on the fear they induced: British intelligence reported they had stolen mustard gas; while a safe house for the gang was reported to contain flasks of botulinum toxin. The stories weren’t true but they could have been.

Almuth Botzenhardt, who grew up in Wormersdorf, near Bonn, during the BMG era recalls that “just the knowledge they were out there led to an atmosphere of paranoia and fear and a polarised political climate. For the general population all this meant roadblocks, a massive armed police presence, helicopters flying over, student houses in my town being targeted by the police…”

When BMG did act its targets were variously the West German police (as upholders of the political status quo), US military complexes (as imperialist oppressors) and Axel Springer’s premises (as a mouthpiece of the state apparatus) or anybody regarded as an upholder or beneficiary of the status quo. In some cases they had less “success” than other similar groups such as Revolutionary Cells or the 2 June Movement, but as a touchstone for militant violence, BMG remains the benchmark. The organisation would kill 34 people in total, while 27 group members or supporters would also die.

Yet the higher up society’s strata BMG aimed, the more determined the authorities became. Eventually the West German state was one step ahead. Baader, Meinhof, Meins, Ensslin and Raspe were arrested in June 1972, convicted after a trial that would run until 1977, and incarcerated in the high-security Stammheim prison. By then Meinhof had already ensured her place in history’s column of notorious faux martyrs by hanging herself in May 1976 (Meins had died on hunger strike in 1974) triggering a hundred conspiracy theories, although it has also been argued she felt an innate sense of failure and had been bullied by Baader and Ensslin.

But while these first-wave protagonists were being brought to justice, accomplices and sympathisers inspired by their actions continued BMG’s violent campaign. If anything those who took up the second-wave cudgels were even more deadly than their famously monikered, now incarcerated, predecessors, culminating in what became known as the German Autumn of 1977. Federal prosecutor Siegfried Buback, a former Nazi, was killed alongside his bodyguard and driver; Jürgen Ponto, the CEO of Dresdner Bank, was shot in an attempted kidnapping; Hanns Martin Schleyer, the chair of the German Employers’ Association, was kidnapped with his captors demanding the release of the gang members in Stammheim; and numerous police officers were killed in gun battles, including Dutch customs officials, as the campaign spilled over the border.

But there was to be a staggering denouement. After members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine hijacked Lufthansa Flight 181, making similar demands to the kidnappers of Schleyer, West German special forces stormed the plane while it sat on the runway in Mogadishu, Somalia, shooting the hijackers and freeing the passengers.

Chancellor Helmut Schmidt was adamant that he would never “sit down and talk to murderers” and had been true to his word. The German authorities lauded their success, until reports came through the following night. Baader, Raspe and Ensslin had killed themselves in their prison cells – attention grabbing to the last. As with Meinhof, conspiracy theories abounded, but most Germans are now of the opinion that is exactly why the suicide pact was carried out, to provoke mistrust of Schmidt and the state. And it got worse. Schleyer, who had been held for more than a month, was murdered the same day.

So far, so much gory politicking. And although the BMG campaign rolled on into the 1980s and 1990s nearly taking with it Nato supreme commander and future US secretary of state Alexander Haig, who narrowly avoided a land mine in an attack in Belgium, it would forever be associated with two of its founders. In the annals of terroristic eponyms their names remain resonant today.

The suicides of young people brought to prominence by events either within or without their control frequently ensures a place in history. If those egregious bedfellows martyrdom and notoriety are the unwitting beneficiaries then infamy beckons. That much is commonplace. But what makes BMG particularly fascinating when viewed from 50 years hence is the level of tacit (if not overt) support from a sizeable section of the West German population and beyond.

In an era where terrorism – for obvious reasons – is pretty much without exception considered wholly depraved, West Germany in the 1970s was more equivocal. Wartime guilt was still running deep among the population, especially – but not exclusively – in the young and anything seen as ‘left-wing or anti-state’ and thus not ‘Nazi or imperialistic” was vicariously supported.

Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre was just one of many intellectuals prepared to defend the group publicly. Which is not to say the government and the security forces lacked the determination to eliminate the gang, nor that people were happy with murderous political fanatics killing at random in their midst, more that BMG represented a break from a dishonourable past, an alternative political option that appealed not only to students or the young, but also to some of those who had lived through the Second World War and the unwelcome revelations about the nation that politically motivated conflict had wrought.

The varied backgrounds of many of the group’s members also held lurid fascination. Gudrun Ensslin was the intellectual daughter of a Lutherian minister. She was of striking appearance and keen mind: shocked into radical politics having spent a year in the US, she embraced the violence of her boyfriend Baader and was arguably the brains behind the entire movement.

Petra Schlem became a martyr for the group when she was the first member to be killed in a shoot-out with police in 1971. She helped cement the group’s bold, devil-may-care fearlessness in the consciousness of the German public.

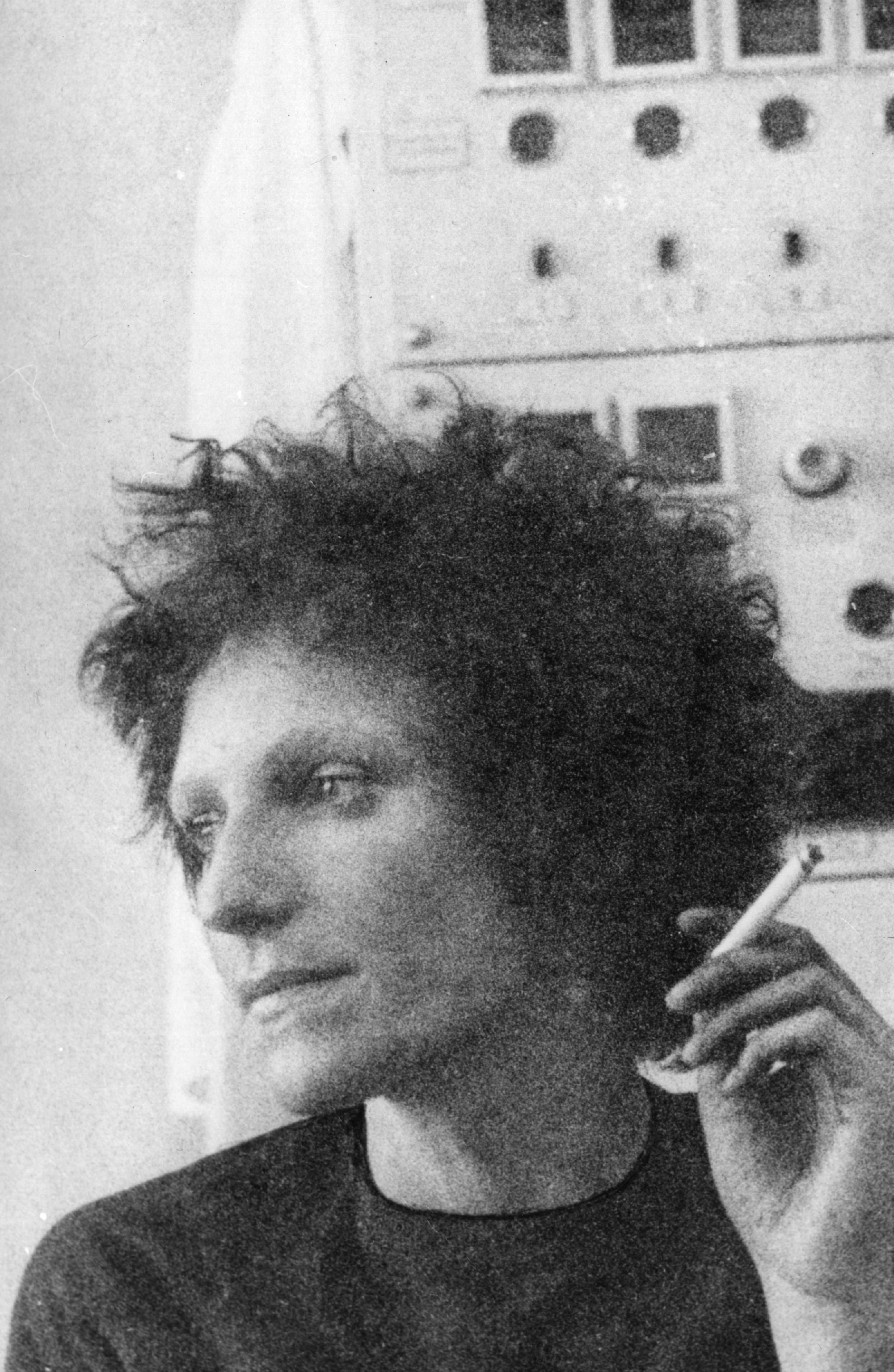

Holger Meins, a student of film, also became a martyr to the cause with his death from hunger strike – public sympathy derived from a man prepared to die for his belief – while Jan-Karl Raspe, who died in the prison suicide pact with Baader and Ensslin, was seen as the conscience of the group, opposed to violence except if it was deemed “necessary”.

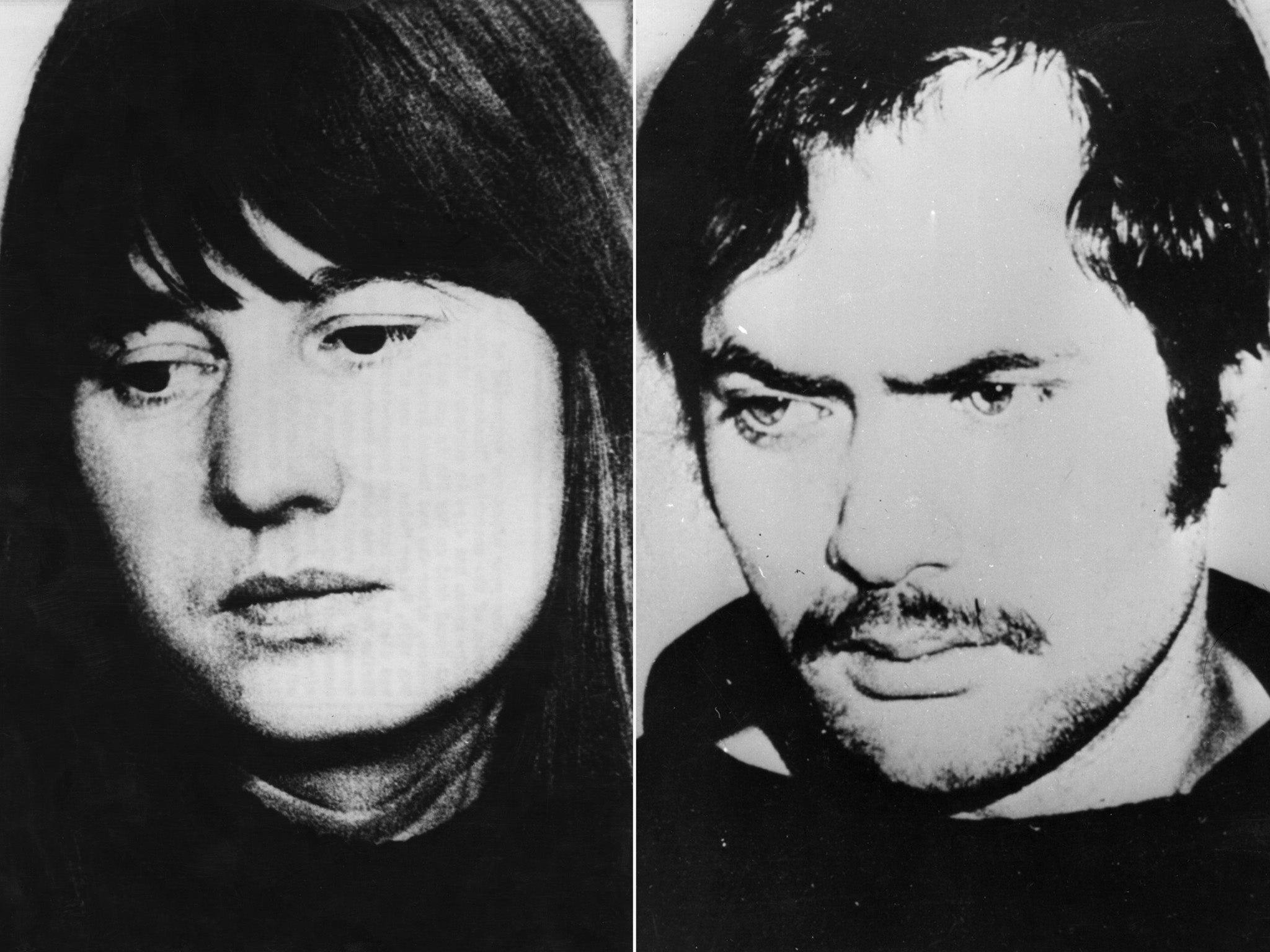

But it was Baader and Meinhof, of course, who gave the group their international identity. Baader was handsome, elegantly dressed and charismatic but violent beyond his involvement in politics. It’s said that had he not been a terrorist, he’d have been a gangster replete with girls, guns and fast cars. Meinhof was quieter, more thoughtful and demure. She had been a prison counsellor and taking the step into violent resistance meant crossing a rubicon. In the end it was effectively a leap of faith – her previously pacifist views cast aside, even possibly in a snap decision taken when she was present at the likely erroneous shooting of a librarian during Baader’s escape from prison in 1970. She was supposedly only there as a reporting journalist but fled with the gang. Like Ensslin, she provided intellectual force to the movement in its early days.

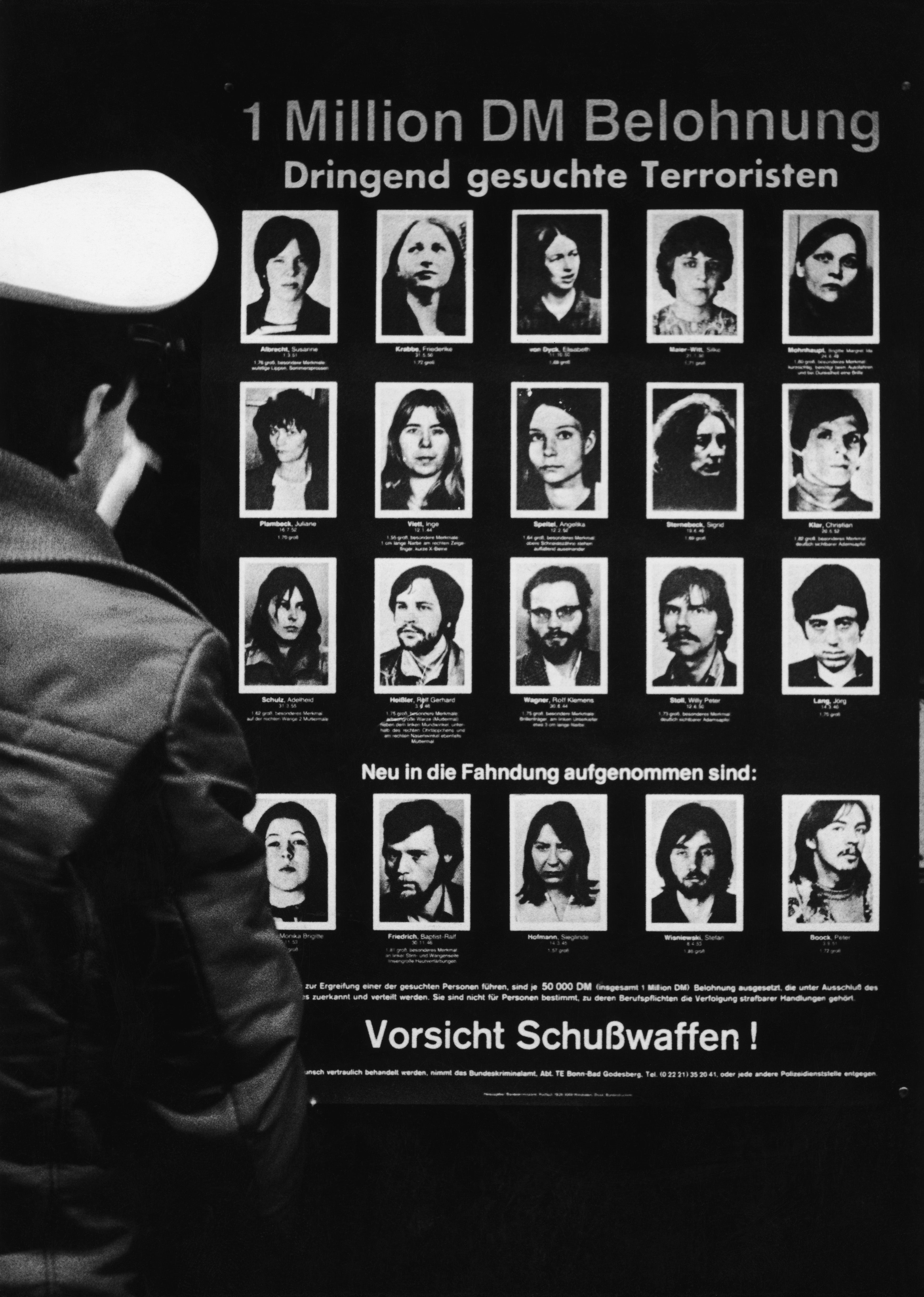

Baader and Meinhof were frequently likened to Bonnie and Clyde – there were even “Wanted” posters in town centres featuring their photographs. But it was not an apposite correlation. The American duo merely wanted a share of the spoils of capitalism via larceny, their German successors intended to remove it from the face of the Earth.

All were excellent manipulators of the media and understood they had a wide reach through a population in thrall either through fear, political sympathy or gruesome fascination. Even the co-ordinated suicide added to the myth of being in control – with the jurisdiction of the state still a laggardly step behind.

If ever “terrorist chic” was “a thing”, this was its time. While the actions of BMG are impossible to justify in any circumstances, their ideologically motivated acts of viciousness are in sharp contrast to the drivers of terrorism in the 20th century – nihilistically right wing or religiously emblematic and driven by a hatred of “the other”; culture wars intended to deconstruct rather than form part of a political vision. BMG, instead, believed it was building something. “They saw themselves as the military wing of a worldwide communist movement,” says Botzenhardt.

Certainly they had rock star kudos, especially among the radical youth. And they were given some slack

Terrorists frequently justify their actions by declaring their targets are legitimate, and the gang’s claims were equally self-deluding. But their selection of victims – bankers, businessmen, judges and American soldiers – had tenuous appeal to a significant section of the population. One survey showed that one in four young Germans felt “a certain sympathy” with the group. One in 10 said they might shield a group member. Even the police were not immune. “It’s fair to say that among younger officers there was qualified admiration,” says Michael Schmidt, a former policeman from Hamburg.

Taking up arms against imperialist oppressors was seen as somehow “ethical”. Even many older Germans did not appreciate former Nazis such as Kiesinger and Richard Jaeger, the minister of justice in the mid-1960s, still sitting pretty in government. It might have remained unsaid among the majority of the law-abiding population, but they would not have been much of an outcry had these representatives of an earlier era been removed from power, even by nefarious means. And it gave weight to the argument that BMG’s challenge to the state was never inarticulate.

“People did sympathise with their aims even if they abhorred their violence,” says Botzenhardt. “Certainly they had rock star kudos, especially among the radical youth. And they were given some slack. The killing wasn’t random and if bodyguards and the like died in the crossfire then they were probably seen as collateral damage, lackeys of the capitalist establishment.” Violent psychosis or direct action? Admirable or appalling, or somewhere in-between?

If the creative arts are any measure of how deep a body has embedded itself into popular society then the amount of literature, cinematography and music disgorged on – if not necessarily glorifying – BMG suggests the group is unlikely to become a footnote in history, and that’s before we start on any number of copycat groups inspired by the gang which sprung up around western Europe and beyond. Which is not to say that, 50 years since they were founded, opinion has not shifted. Where once there might have been qualified admiration the world now has a different perspective on violence as a means of achieving an aim, political or otherwise. Social engineering using bullets just isn’t cool anymore.

“The killing of Schleyer changed things,” says Volker Sommer, 71, from Bielefeld, who was a student when BMG was beginning to organise. “Any support and any secret sympathy for the group stopped at that point.”

The world and politics has moved on. Terrorism appears more nihilistic now. In retrospect perhaps BMG looks almost quaint – an ideological throwback. When Der Baader Meinhof Komplex, a film documenting the group’s reign, was released in 2008 it split opinion. Did it glorify them – they were featured as good-looking and dressed in the fashions of the seventies – or merely chronicle their undoubtedly notable story? It was a contentious argument but what also emerged was that BMG represented history, not the Germany of today – a progressive, European-Union embracing, open-minded political reality.

The group’s ideology was not always especially “pure” either, many were antisemites demanding the overthrow of the state of Israel – indeed former lawyer and gang member Horst Mahler has pretty much come full circle; a holocaust denier imprisoned for inciting racial hatred – while feminism, despite the prevalence of woman in the group, was regarded as something of a bourgeois affectation. Baader was known to refer to female members of the organisation as Votzen (or c**ts). Those close to him say he complained endlessly, blaming any failures on others and had “the personality of a sociopath”. In that sense Stefan Aust, author of the book on which the 2008 movie was based, believes Baader does share a link to those involved in terrorism in the 20th century. “Baader was not so different from Mohammed Atta, one of the ringleaders of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York. Both wanted to be martyrs and to gain immortality through their deaths,” he argues.

BMG also mainly shunned the socialism of the eastern European nations under the influence of the Soviet Union, arguing that theirs was a distorted authoritarian form of genuine communism that had its own inbuilt imperialism. Nonetheless, later investigations found they had, at times, been funded and given refuge by the East German secret police – the notorious Stasi.

Baader, Meinhof and their cohorts didn’t, in the end, change the world. Indeed, it’s often suggested they left a stain on the democratic left wing in Germany, disowned by those who might have shared a kindred spirit, an embarrassment to a tolerant world they seemed to eschew. In prison Meinhof admitted that the group was not so blind as “to think they would bring about revolution in Germany. Frankly, they just scared a lot of otherwise progressive people into thinking the revolution was not for them,” said Siegfried Haupt, a former Green councillor from Hamburg who was 18 when Schleyer was murdered.

And although Schleyer and other people assassinated by the group – all from the higher strata of society – might also have raised the political ire of their democratic opponents, sympathy for them and their families at the barbarity of their slayings meant that even people who understood BMG’s aims did not believe the means justified the end.

And there’s a further paradox. If BMG’s members were outraged at the presence of former Nazis in the post-war German government, some in Germany have questioned former sympathisers of the group filling roles in politics, media and culture today, former foreign minister Joschka Fischer among them. “Is there a difference?” asks Haupt. “Both groups condoned the murder of sections of society they deemed degenerate.” Botzenhardt, however, feels that the two situations are not identical. “Sympathy for the aims of Baader-Meinhof did not necessarily translate into violence,” she says. “Whereas there can be no such equivocacy when it comes to Nazism.”

Most Germans have now come to terms with their country’s past in a way that seemingly BMG could not. The German word Vergangenheitsbewältigung means “coping with the past” through confronting the nation’s history while living a life free from the guilt and rancour of previous eras. This process more than anything rendered the objectives of BMG somewhat obsolete.

“Their legacy isn’t really an issue today,” says Sommer. “If it is ever mentioned it is seen as a group of young people who grew out of the student generation of ’68 and who wanted to change what they saw as a ‘pig system’. But in the end they were just ordinary criminals and murderers.”

Sommer’s is a commonplace view in today’s Germany. But, 50 years on, has the misplaced glamour fully dissipated? New York’s Museum of Modern Art features photographs of the Baader, Meinhof and Ensslin suicides as part of its permanent collection. And, you can still buy a T-shirt with Andreas Baader’s gun and star emblem on it. There’s even one emblazoned with the words “Prada-Meinhof”. Terrorist chic still? Depends if it ever was.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments