The maverick Harvard physicist who believes in aliens

Our knowledge is just an island in an ocean of ignorance and there is a lot to discover, says controversial professor Avi Loeb in his new book. James Wilkes speaks to him

Avi Loeb doesn’t care if people think he’s a maverick. He explains it like this: one day, when he was a boy at school, he entered the classroom and saw the other children jumping on their desks and stopped to watch. When the teacher came in she said, look at Avi, he is so well behaved. “I was not particularly well behaved,” he told me recently. “I was just wondering whether it makes sense to jump around. I don’t do what everyone else is doing because I want to think about it for myself.”

Little has changed in the 50-plus years since then, and maverick is a word frequently used to describe the Israeli-American theoretical physicist since the arrival of Oumuamua in our solar system, the unidentified interstellar traveller first spotted by the Pan-STARRS telescope at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii, on 19 October 2017.

The following year, Professor Loeb, who is the Frank B Baird Jr Professor of Science at Harvard University, made worldwide headlines after publishing a paper suggesting the object might be a wafer-thin solar sail built by an advanced extraterrestrial civilisation. It was a view that placed him firmly outside scientific orthodoxy, which prefers to characterise Oumuamua as having a natural origin. More than three years later, Loeb – whose book, Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth, was published last month – is unconcerned about the mainstream opinion.

Loeb grew up on a farm in Israel and did not always want to be a scientist, having initially been drawn to philosophy – although he readily sees the close link between the two disciplines. “Of course, people can be exceptional scientists by narrowing their focus to a narrow niche and they become world experts and find new things. But there are sometimes conceptual issues that come up in physics and you need this broader view to deal with them.”

The big discoveries in science, he believes, come from people who take this “broader view”. He suggests a pragmatic outlook offers “alternative explanations” and points out that Albert Einstein hit upon his general theory of relativity after reading great philosophers including, for example, Karl Marx.

All of which brings us neatly to the object formally designated 1I/2017 U1 – more commonly known as Oumuamua – meaning “scout” in the Hawaiian language.

Experts were able to study the object for just 34 days before it ceased to be visible to telescopes, and as a result the information they gleaned is limited. Little is known about Oumuamua’s place of origin or chemical composition. Estimates suggest it is roughly half a mile in length, either circular or cigar-shaped, and 10 times as long as it is wide. As it heads out of the solar system, it will travel in the direction of the constellation of Pegasus.

Oumuamua didn’t have a cometary tail, but there it was, pushed away from the sun by some force. It was not clear what provided this force

Controversy about precisely what Oumuamua was (and is) has raged ever since it was first spotted, travelling at a speed of more than 54 miles per second.

Loeb divides the scientific community into three groups. “There is the group consisting of people who are not really practising science,” he says. “They are writing blogs or newspaper articles or popular books and I don’t really pay attention to what they say because they are not practising scientists.

“Then you have most of the mainstream community that says ‘I don’t care about the details, business as usual’, which may leave them in their comfort zones but they don’t attend to the anomalies of the subject.

“And then you have people who really pay attention to the details of the subject – and they are very unusual details.”

In comparison with the numerous comets and asteroids that populate the solar system, Oumuamua is clearly an outlier. “It didn’t have a cometary tail,” Loeb says, “but yet there it was, pushed away from the sun by some force. It was not clear what provided this force and it had an extreme geometry. There are several anomalies that come up, including the fact that the object is most likely flat, and people try to explain this as being from a natural source.”

To do so, mainstream scientists have developed what Loeb regards as outlandish theories. For example, some people have suggested we don’t see the cometary tail because it’s made of pure hydrogen, which is transparent so it cannot be seen but it exists. But Loeb believed that the problem with that is that the hydrogen iceberg would evaporate quickly along the way and would not survive the journey.

“Then there is a suggestion that perhaps it is a cloud of dust that reflects sunlight and then gets pushed,” says Loeb. “Again, that wouldn’t survive because it would need the density of this object to be 100 times less than that of air, so, very fluffy.”

Loeb is also the chairman of the advisory board for Breakthrough Starshot, an ambitious project to send a probe to Alpha Centauri, 4.37 light years away, using technology strikingly similar to that which he theorises may have propelled Oumuamua – including a lightsail.

Asked about the obvious parallels, he says: “My imagination is limited to my experience. The fact that I’m involved in the development of lightsail technology shapes my thinking and allows me to imagine something like that. So I won’t deny that – but at the same time it may well be a technology that is very often used by other civilisations.”

His radical paper, co-written with postdoctoral student Shmuel Bialy and published in 2018, threw the cat among the pigeons.

“We suggested originally that it may be like a sail that you find on a boat, except that instead of being pushed forward by reflecting the wind or air molecules, it’s reflecting light, sunlight, and that is called a lightsail. We are currently developing this technology for space exploration, so it’s possible that it exists out there if another civilisations were more mature than we are.”

Loeb believes the bottom line is that if all those who think the object came from a natural origin are contemplating anomalies that we haven’t seen before, then why not an artificial origin? “In fact,” he says, “it seems like a better explanation for all the properties of Oumuamua.”

In essence, Loeb’s theory is that Oumuamua is very thin – possibly just one millimetre in width – enabling it to be propelled by reflected sunlight. To support his theory, he offers a separate, less mysterious, example, saying: “It turns out that in September, 2020, just a few months ago, there was another object. This one was bound for the sun. This also exhibited an extra push away from the sun due to reflection of sunlight and didn’t shine a cometary tail.”

In this instance, scientists concluded the object was a Centaur upper-stage booster rocket from the Surveyor 2 mission that launched to the moon in 1966.

He explains: “It was a hollow and thin surface that allowed the reflection of sunlight to move it because it had a large area for its weight. We know that we produced this object, that it’s artificial – but we don’t know who produced Oumuamua. It may not be a lightsail per se – by design it may be a surface layer of a spaceship that was torn apart or some equipment that serves another purpose.”

Loeb is keen to emphasis he is not providing definitive answers, saying: “I don’t know for sure because we didn’t get enough evidence but I say that this is a very serious possibility that we have to contemplate.”

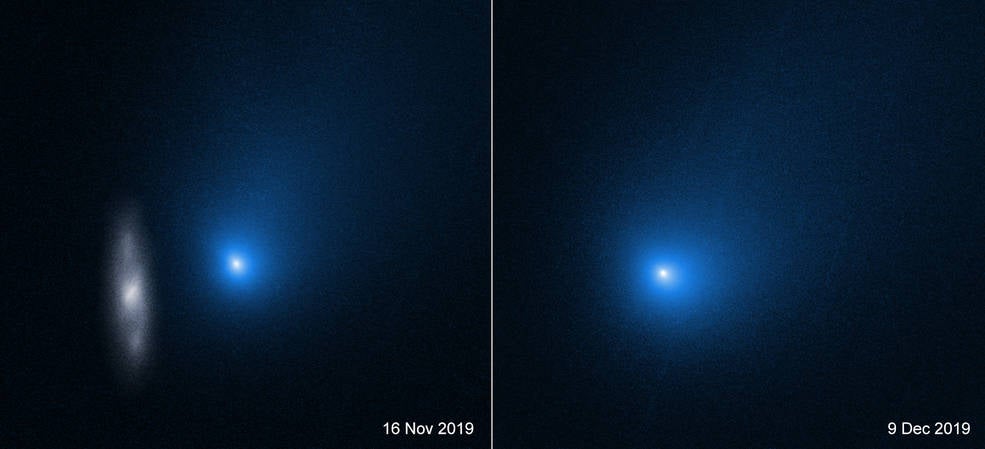

Less than two years later, another interstellar visitor was spotted by Gennadiy Borisov, an amateur astronomer in Ukraine, and was subsequently named 2I/Borisov in his honour. For Loeb, Borisov simply underlines precisely how unusual its predecessor was.

“Borisov looked just like a regular comet with nothing unusual about it,” he says, “and people asked me, ‘does that convince you that Oumuamua is also natural?’ and I said that you know if you find a plastic bottle and afterwards you find a lot of rocks, it doesn’t make the plastic bottle a rock.”

After the publication of his paper, Loeb has faced scorn and even hostility from many of his colleagues. He says that many people criticised his idea but did not provide specific alternatives to explain the anomalies of Oumuamua. In particular he cites one paper published by the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) and authored by, among others, Michele T Bannister of the Astrophysics Research Centre, Queen’s University Belfast and Asmita Bhandare of the Max Planck Institute, which insists: “In all cases the observations are consistent with a purely natural origin for Oumuamua.”

Simon Goodwin, professor of Theoretical Astrophysics at the University of Sheffield, even wrote for The Conversation that Loeb “may or may not be right, and there is no way of proving or disproving this idea. But claims like this, especially from experienced scientists are disliked by the scientific community for many reasons.”

Loeb reflects on this treatment and recalls a seminar about Oumuamua. When the seminar was over and he left the room, a colleague turned to him and said, “this object is so weird, I wish it never existed”.

This scepticism also relates to mankind’s view of itself, he suggests. “With respect to the subject of intelligence and extraterrestrial intelligence and civilisations, people prefer to believe that we are unique and special because it flatters our egos.”

No fan of science fiction, despite the superficial similarities between his explanation of Oumuamua and the novel Rendezvous with Rama, Loeb adds: “The literature of science fiction and unidentified flying objects is also regarded by scientists as not scientific – they worry that it may degrade their discussion.”

Loeb has no doubt Oumuamua represents the most convincing evidence for an extraterrestrial civilisation ever discovered

Nevertheless, Loeb emphasises the importance of scientists sticking to the facts and applying tried and tested methods, irrespective of the disapproval of their peers. He highlights two specific approaches when it comes to searching for extraterrestrial civilisations; the first is that you can search for radio signals, similar to having a phone conversation – although that would require the counterpart to be alive at the same time you have the conversation. The second is to wait for a letter in the mail.

“If the delivery takes a long time then the person on the other side may not be alive anymore,” Loeb says. “And so that offers you a better perspective for finding clues about the cultures that existed in the distant past.”

Loeb, who describes such an approach as space archaeology, adds: “We cannot have a phone conversation with the Mayan culture because they are not around anymore, but we can find their relics and it’s like doing archaeology in space, finding objects such as Oumuamua that came into the solar system from far away.”

Loeb has no doubt Oumuamua represents the most convincing evidence for an extraterrestrial civilisation ever discovered. “Other than Oumuamua, we had some radio signals that looked unusual but they were never stronger evidence than this, and most likely they were environmental. There is no other case that looks as promising.”

Ultimately, Oumuamua is this: the tantalising possibility of a discovery that would revolutionise mankind’s understanding of the universe – which is Loeb’s primary motivation.

“Science is not about glorifying ourselves as scientists and illustrating that we are smart,” he says. “It’s more about finding out new things about nature and figuring things out, gaining knowledge about how nature works. Our knowledge is just an island in an ocean of ignorance and there is a lot to discover and I enjoy this pursuit.”

‘Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth’ is published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments