How Auguste Escoffier changed dining forever

So much of what we take for granted about fine dining today comes from one man who was born 175 years ago. Mick O’Hare tells his story

Think gastronomy, think French food. English-speaking diners have even adopted French to describe our eating experiences. The term haute cuisine points us firmly in the direction of Rue Montorgueil or Rue Cler whose restaurants and brasseries ensure that Paris remains the epicurean capital of the world.

Yet so much of what we take for granted about fine dining today, and even food and restaurants in general, we owe to a man who forged a reputation far away from the boulevards of Paris, or Monte Carlo, the playground of the bon vivant.

Georges Auguste Escoffier – who was born this month 175 years ago – was, at first, a reluctant chef. But he would go on to pretty much single-handedly choreograph and codify haute cuisine, elevating his profession to one of critical acclaim.

He was also the world’s first celebrity chef, attracting the wealthy and aristocratic, first to Monaco and Lucerne but latterly and, above all, to London where he served monarch, magnate and matinee idol. Decades before the nation was introduced to the likes of Delia Smith or Jamie Oliver, Escoffier was publishing books that became bibles of gastronomy. He was to food what Caruso was to opera and Bradman was to cricket. Even the slang term “scoff” can be laid at his oven door.

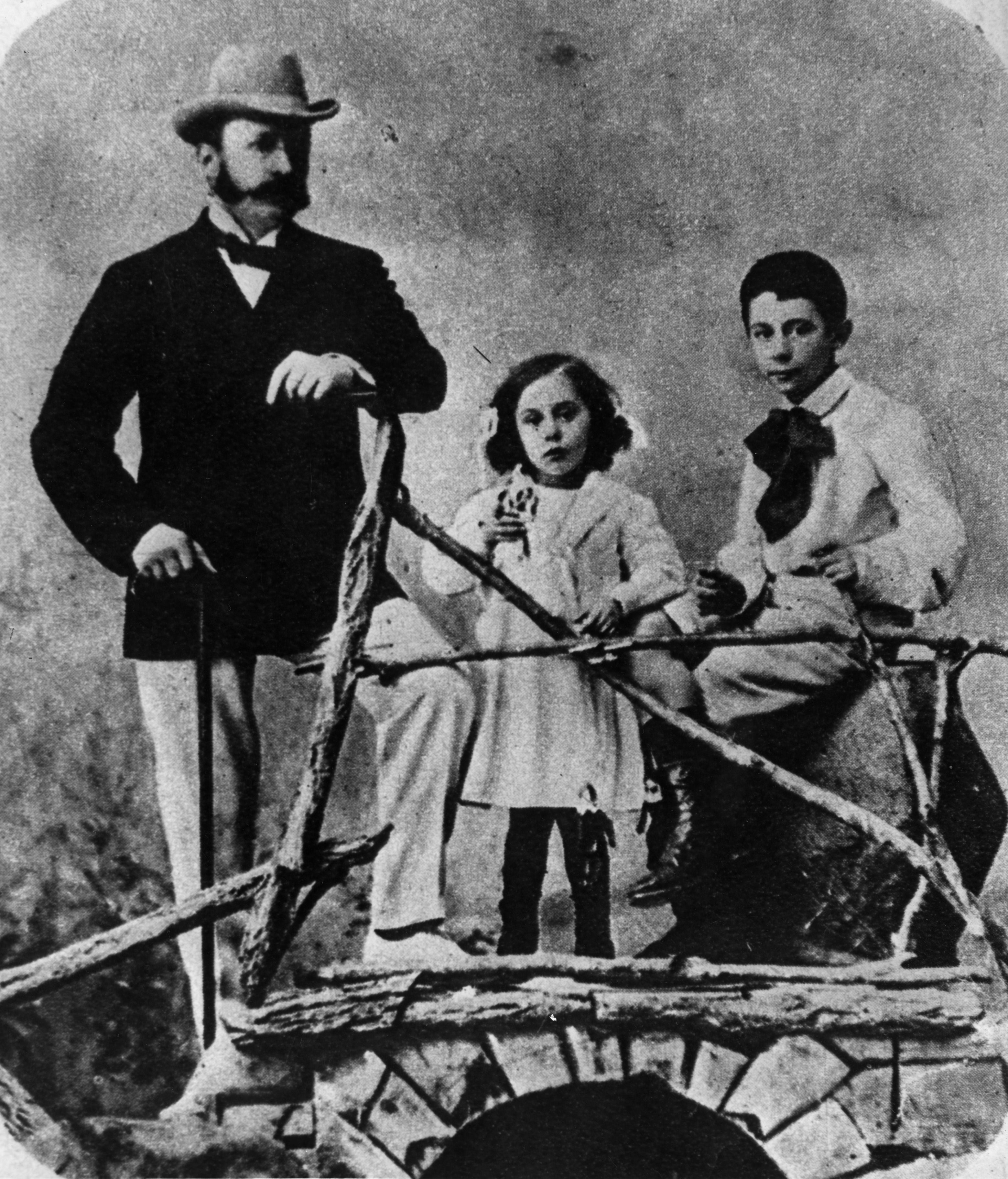

As a child, Escoffier had dreamt of becoming an artist, but his lowly background as the son of a Provence blacksmith meant his creativity and single-mindedness were to be channelled in a different direction. In 1859, when he was 13, his family sent him to work with an uncle who owned a restaurant in Nice serving the European elite who spent much of the year on the French Riviera.

He was shocked by what he found. Having expected the kitchen of a fine-dining establishment to be serene and sedulous, he instead encountered disagreement, shouting, overwhelming heat and smoke, violence and a staff that spent most of the day in an alcoholic haze. His uncle was a bully and his colleagues indolent. But it provided him with a purpose – to change the culture of the kitchen. “I had not originally intended to enter this profession but since I was in it, I decided to do my best to raise the prestige of the chef de cuisine,” he wrote later.

His diligence, skill and aptitude as he learnt the sometimes intricate techniques of the kitchen were quickly noticed and he was offered a job in Paris. However, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 intervened. Escoffier was conscripted as a cook during which he fed the Army of the Rhine HQ during the 10-week-siege of Metz. It was during his time in the military that became fascinated with food preservation in order to feed large units of soldiers on the move. He would later become the first person to can tomatoes commercially. After being discharged he moved to Cannes to start his own restaurant Le Faisan d’Or where he met and married poet Delphine Daffis.

The restaurant was a huge success and word spread. In 1884 he was approached by César Ritz the manager of the Grand Hotel, Monte Carlo to head up the kitchen during the winter season when the titled and well-heeled of Europe would decamp to the Riviera. During the summer months, Ritz sent him to Lucerne to work in another of his establishments, the Grand Hotel National.

And it was here that the two, between them, developed their vision for what modern hotel dining should look like, and formed the relationship that would ensure fame and, as fate would have it, notoriety. Ritz was dynamic and charismatic, understood what made for perfect service, and had a talent for ensuring the desires of his wealthy guests were met, often before they became aware themselves. His introduction of pink tablecloths to reflect a flattering, rosy hue onto female diners’ faces was a typical touch.

Escoffier meanwhile was the perfectionist behind the scenes. His kitchens were methodical and synchronised. Calm ruled and professionalism proliferated, an environment that ensured his culinary genius could come to the fore.

Meanwhile, as their joint reputation grew, in London Richard D’Oyly Carte had opened The Savoy Hotel in 1889. His vision was of London’s first true luxury hotel and that included haute cuisine. Part of D’Oyly Carte’s plan was to open a restaurant that local people with money would choose to dine in. He had stayed at the Monte Carlo Grand Hotel and had met Ritz.

Later Escoffier would remark that Britain had no dining tradition, except in the homes of the wealthy. He thought the natives had unimaginative palates

He invited him to London. “It wouldn’t be a restaurant only for hotel guests,” explains Susan Scott, The Savoy archivist, “but for London’s local wealthy population, along the lines of the American hotels D’Oyly Carte had stayed in while touring the States with his D’Oyly Carte Opera Company.”

Initially, Ritz was only hired for six months, “but when the aristocracy from the Prince of Wales downwards plus wealthy and fashionable London began to arrive at The Savoy’s front door, D’Oyly Carte realised he needed to renew his contract,” says Scott.

Ritz’s address book was legendary. D’Oyly Carte and his fellow directors at The Savoy believed that his powers of persuasion and his reputation for impeccable service would appeal to and attract well-to-do diners. D’Oyly Carte loved Ritz’s theatricality with the guests – flowers for female diners and free champagne – but Ritz himself knew that this would only take the restaurant’s reputation so far. What it needed to maintain its success was Escoffier.

“He had a stellar reputation in France but was barely known in London,” explains Scott. Later Escoffier would remark that Britain had no dining tradition, except in the homes of the wealthy. He thought the natives had unimaginative palates and feared that diners used to British cuisine would turn their noses up at culinary sophistication.

He proved himself wrong and it was to be in London where his reputation was cemented. Ritz – and more than adequate remuneration – helped to convince him that D’Oyly Carte shared their vision, and in 1890 they set up shop together at The Savoy.

Escoffier immediately installed his own team.

“The original chef and kitchen brigade weren’t pleased,” says Scott. “They salted and spoiled the food before Escoffier started on Easter Sunday. He had to borrow ingredients from the chef at the Charing Cross hotel just down the Strand from The Savoy.”

Lunch service went ahead as normal and in the weeks after he set about transforming the kitchen, introducing the hierarchical brigade de cuisine system based on his military experience. Everybody knew their function from the chef de cuisine at the top, to the sous chef, to the commis chefs, to the dishwasher at the bottom. It was akin to the revolution in car production Henry Ford would implement early the following century with his Model T assembly lines. Escoffier was, in effect, the creator of the modern restaurant kitchen.

“He still had extensive menus, but he made the whole system more coherent. Dishes were cooked to order and it is so efficient that it remains the basis for running a restaurant kitchen to this day,” says Scott. Food service was also radically simplified by using local, seasonal produce with no elaborate garnishes, still the essence of today’s haute cuisine. That a table of four can each order different dishes yet see them all arrive at the table simultaneously is all down to Escoffier.

He was a stickler for discipline – no swearing or drinking in Escoffier’s kitchen, he replaced beer with a hydrating malt brew – and hygiene. The uniform, from the hat to the neckerchief to the trousers that we so readily associate with chefs today was first introduced by Escoffier. “Wearing white you can see where the spillage is and you can also boil whites without them losing colour,” says Scott. Staff were banned from wearing them beyond the kitchen confines too.

For all the fame Escoffier had garnered in Lucerne and Monte Carlo, London was, at that time, the capital city of the biggest empire the world has ever seen. What happened in London had repercussions around the globe. And as his reputation grew Escoffier became an international celebrity. “I am the emperor of Germany but you are the emperor of chefs,” was how Kaiser Wilhelm II described him.

The Prince of Wales – the future Edward VII – had already been charmed by Ritz, now he was enthralled by Escoffier. As was most of London society including the prince’s mistress Lillie Langtry.

It was also a time when society was slowly democratising, the role of women was changing and Escoffier and Ritz saw the opportunity. “Dining out had been a predominantly male affair,” explains Scott. “The Savoy had two restaurants, the Grill downstairs which was essentially a gentlemen’s club – with simple dishes, a bar, smoking and billiards – and the restaurant on the second floor.” The latter is where Escoffier and Ritz worked their magic, ready to serve the changing mores of Victorian society. The Savoy Restaurant became a place to be seen as much as it was to eat.

“For the first time, upper-class ladies were allowed to dine in public in The Savoy Restaurant,” says Scott. Because full evening dress was required it attracted women who for the first time could dine alone and, crucially, show off a new gown. And it wasn’t just aristocracy who were drawn to The Savoy Restaurant, the burgeoning nouveau riche were also welcomed.

Essentially Escoffier invented modern dining as we know it today, making food accessible and less elitist but maintaining the joy of consuming it in fine surroundings. He had introduced the prix fixe menu in Monte Carlo – a fine dining experience at a set price – and in London, as the newly wealthy middle class came to dine at The Savoy, this came into its own. “It attracted those who wouldn’t or couldn’t eat a formal eight or nine-course meal,” says Scott. “It cut through the banqueting table approach, a smaller meal but of exceptional quality. It proved very successful which is why it’s still around today, pretty much throughout the world.”

Escoffier’s predecessor as the “world’s most renowned celebrity chef”, Marie-Antoine Carême had cooked for the likes of Napoleon, Talleyrand and Tsar Alexander I, producing elaborate banquets replete with ornate table designs created from icing, gelatine, marzipan and fruit, all intended to impress his patrons. Escoffier dialled this down – “Faites simple” (don’t complicate things) was his mantra – and while not entirely dispensing with tradition he codified the haute cuisine of his predecessor by defining the five classic mother sauces of French cooking (Hollandaise, Bechamel, Veloute, Espagnole and Tomato) from which daughter sauces, such as Bernaise, Mournay or Chasseur could be prepared. It was art verging on science. His dishes were still elegant but lighter than those of the past, focusing on the flavour of their fine ingredients.

Escoffier’s habit of offering dishes based on famous individual diners charmed the great and good, attracting royalty and artists alike, hoping their fame might be so rewarded. Actress Sarah Bernhardt (to whom Escoffier dedicated a strawberry dessert) and Benoît-Constant Coquelin (for whom he prepared sole) were frequent diners. Peach Melba (and Melba toast) were dedicated to Dame Nellie Melba, the Australian opera singer.

Following his departure from The Savoy he would write Le Guide Culinaire (published in English as A Guide to Modern Cookery). It is still regarded as the first bible of French cooking. His methods were the natural evolution of haute cuisine, and Le Guide Culinaire was effectively a gastronomical oral epic – everything he had been espousing in the kitchen distilled down into a book.

Yet despite his focus on simplicity and discipline Escoffier was still an innovative culinary impresario creating dishes that still appear on tables today: bombe Nero, tournedos Rossini and pommes dauphine. “He was the first person to serve frogs legs in England,” says Scott. Although he knew the Prince of Wales had eaten them before, he surmised that the rest of British high society might not be so keen. So, at a dinner for the prince, he served them in aspic, calling them The Thighs of Dawn Nymphs. “The Prince of Wales was a man who himself was probably no stranger to the thighs of a nymph at dawn,” remarks Scott dryly, “and they went down a treat with the rest of the diners too.”

It was a disappointing ending because Escoffier was brilliant. Ignoring the backhanders, he was a superb, creative individual. Amusing too

But aware of the success of The Savoy Restaurant and its dream team of Ritz and Escoffier, other entrepreneurs were looking to exploit the subtle changes in London society and were taking note. A new wave of hoteliers was descending on the city and they were casting their gaze in the direction of The Savoy’s two leading lights.

Ritz had built into his contract with The Savoy the proviso that he could spend six months a year conducting his own business. A syndicate hoping to build a new hotel, the Carlton, on London’s Haymarket hired Ritz to advise them. It would change the direction of his career, and that of his star chef, because here’s the kicker: Ritz and Escoffier were on the make.

Savoy management first became suspicious in 1895 when profits from the restaurant business were not at the levels they had expected. “Two issues were in play,” says Scott. “Ritz enjoyed spending other people’s money and was meeting with the Carlton businessmen – and many others likely to further his interests – on The Savoy’s premises, entertaining them lavishly with food and drink paid for by the hotel.”

Management might have turned a blind eye considering the benefits Ritz brought to their business except that by 1897 the kitchen was actually showing a loss despite the evident success of the restaurant. It turned out that the suppliers of produce to the kitchens had been providing Escoffier with kickbacks and gifts. “It was commonplace in Paris, but not in London,” says Scott. If 500 eggs were ordered, only 350 might arrive and Escoffier would pocket the difference. He also set up his own company to supply food to The Savoy at inflated prices. “Suppliers had kept quiet because they didn’t want to lose the business,” she adds.

In total, sums reaching £1m in today’s money were involved. Ritz and his financial controller Louis Echenard along with Escoffier were called into D’Oyly Carte’s Office on 7 March 1898 and asked to leave quietly. That they didn’t, meant that news reached the press. On 8 March The Star newspaper wrote: “During the last 24 hours The Savoy Hotel has been the scene of disturbances which in a South American Republic would be dignified by the name of revolution. Three managers have been dismissed and 16 fiery French and Swiss cooks (some of them took their long knives and placed themselves in a position of defiance) have been bundled out by the aid of a strong force of Metropolitan police.”

Eventually, with no admission of wrongdoing, Ritz and Echenard repaid £4,173 to the hotel, plus an additional £6,377 from Ritz himself to cover the “astounding disappearance of over £3,400 of wine and spirits in the first six months of 1897” as well as “the wine and spirits consumed in the same period by the managers, staff and employees amounting to £3,000.” Escoffier himself had probably gained to the tune of £16,000 but, without the means to pay, the hotel accepted £500 from him.

Scott notes that: “It was a disappointing ending because Escoffier was brilliant. Ignoring the backhanders he was a superb, creative individual. Amusing too. And the truth is he and Ritz would probably have left anyway to go to the Carlton.”

Ritz’s famed address book meant that his friends in high places were always likely to side with him. The Prince of Wales announced: “Where Ritz goes, I go,” says Scott. So fashionable society immediately followed him to the Carlton where Ritz and Escoffier were soon repeating their double act. Ritz would go on to open hotels in his name in Paris, London and Madrid before his retirement.

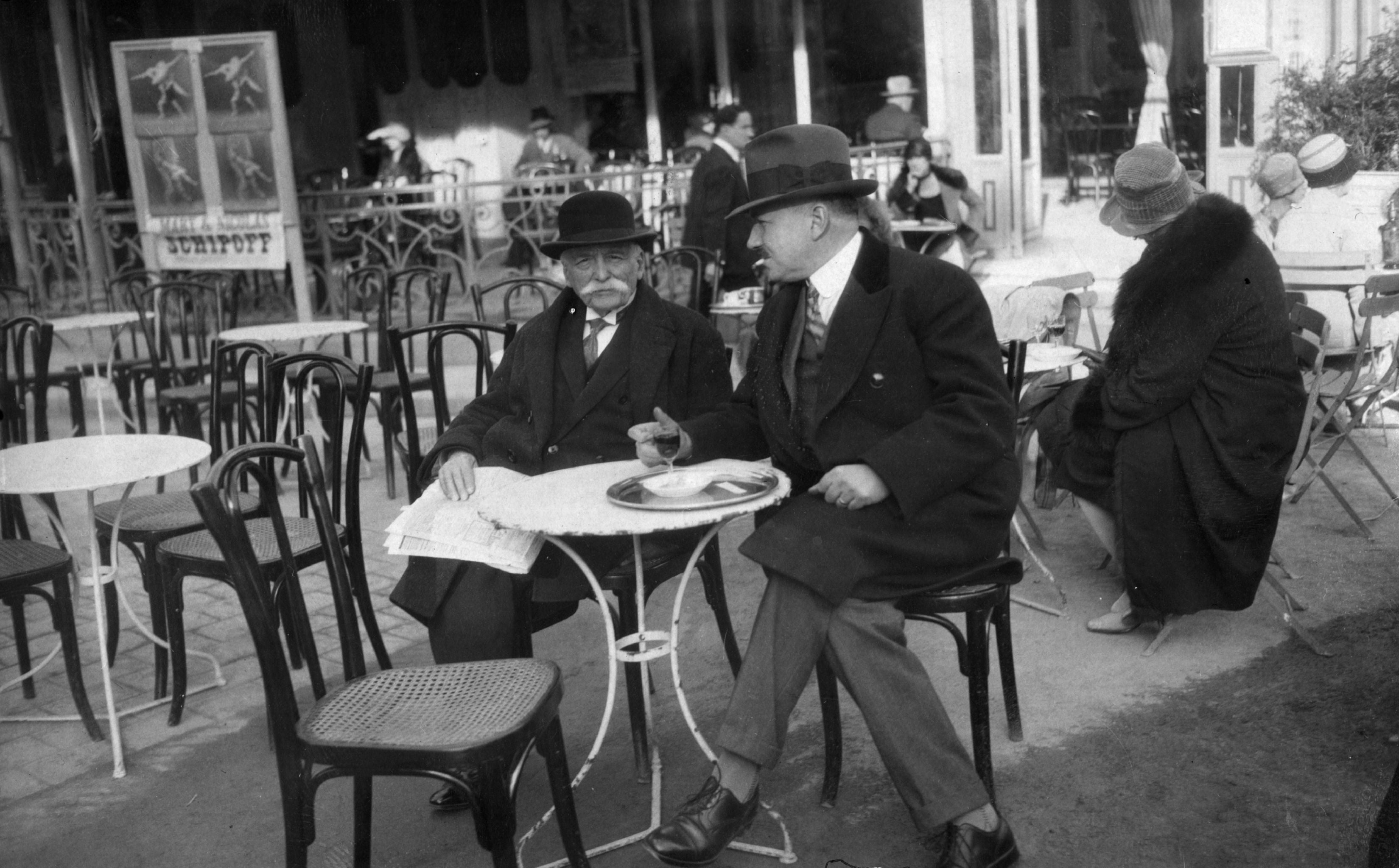

Escoffier would maintain and enhance his reputation at the Carlton and would open kitchens in places as diverse as the Ritz-Carlton in New York and aboard the luxury ocean liners of the Hamburg America Line. But he wasn’t good with money. After losing a son, Daniel, in the First World War he retired on modest savings to Monte Carlo aged 74 after 62 years of working in the kitchen. He was awarded France’s highest medal, the Légion d’honneur, and died six days after his wife in February 1935.

Whether there is irony in the fact that the father of modern French haute cuisine was based in London is a lesser consideration than the fact that almost 176 years after his birth his reputation as a culinary virtuoso survives intact. His books remain French cookery’s literary touchstone. The house where he was born in the village of Villeneuve-Loubet is now the Musée de l’Art Culinaire, run by the Foundation Auguste Escoffier.

“He reigned supreme as maître-chef,” says Scott. “The greatest exponent of French haute cuisine.” Despite the scandal, the restaurant at The Savoy, now run by celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay, still offers menus in Escoffier’s name. Its new title, 1890, is a nod to the year Escoffier began working in London.

Paul Levy, co-chair of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery and the man who did much to expose the extraordinary story of Escoffier’s expulsion from The Savoy kitchen wrote that, despite his failings, Escoffier “raised the social status of the chef to a level that anticipated today’s celebrities. He is a hero to today’s chefs.”

Ramsey, Oliver, White and Stein – they are all the direct descendants of Auguste Escoffier. And whenever we eat at a restaurant, even the most humble, we are still experiencing a tiny part of the revolutionary practices the king of chefs and the chef of kings set in motion more than a century ago.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments