The short and salacious story of Aubrey Beardsley

In just a six-year career, the art nouveau illustrator’s line drawings shocked and titillated Victorian society, but left a lasting impact on the art world far beyond his short life, writes Olivia Campbell

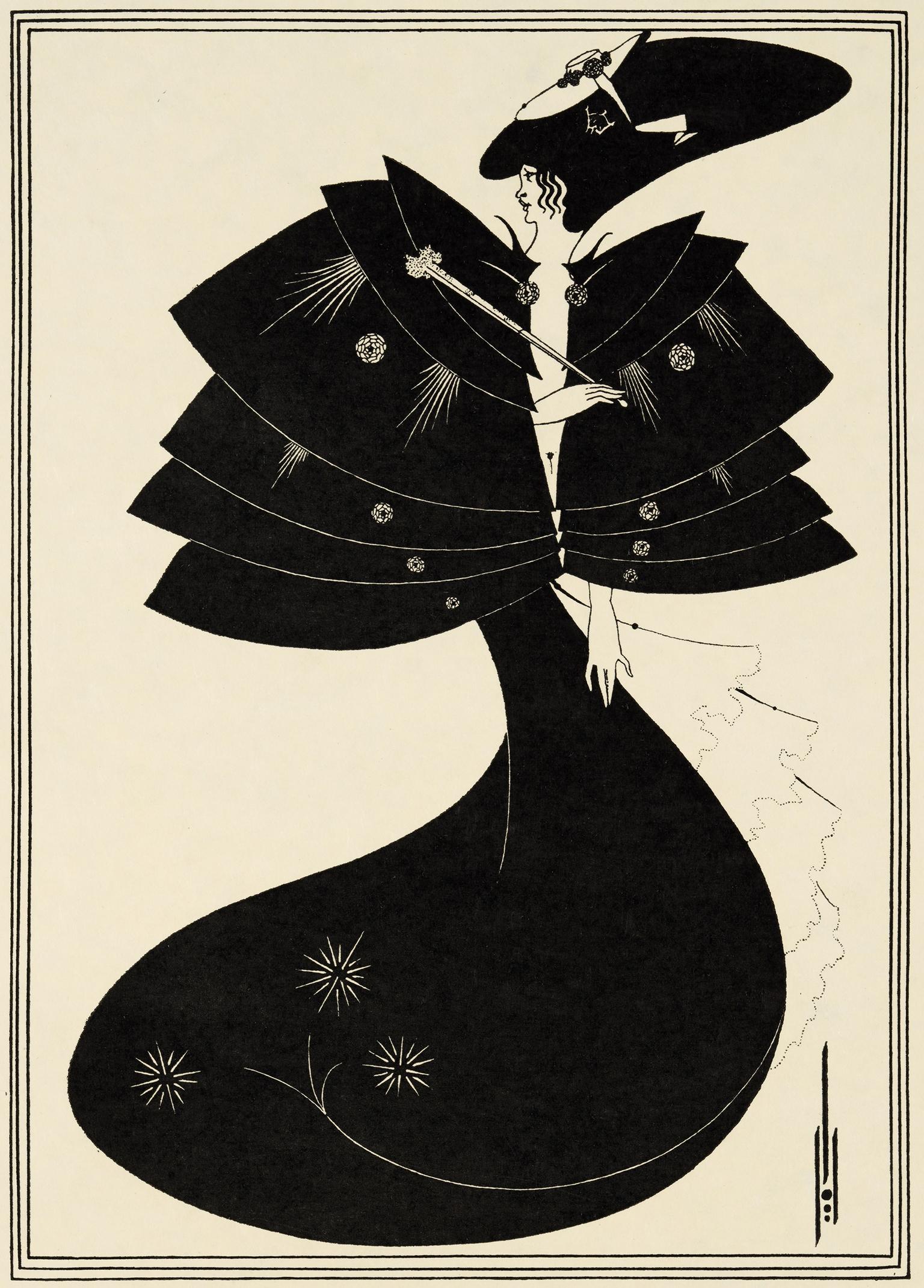

I have one aim – the grotesque. If I am not grotesque, I am nothing.” Such spirited words, spoken in 1896 by notorious illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, sum up one of the most infamous figures to unleash havoc upon the prim and proper cultural elite at the end of the 19th century.

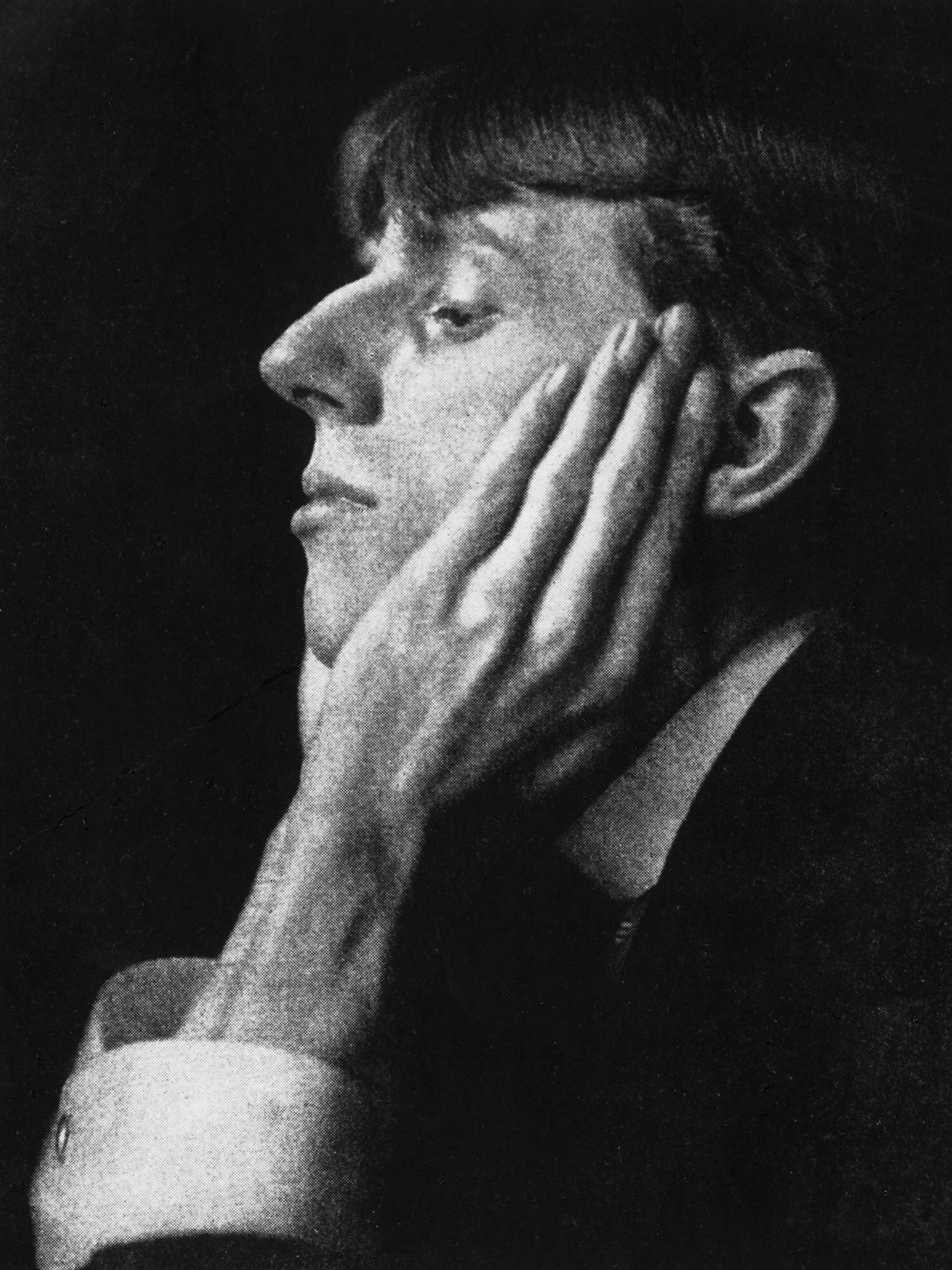

Before tuberculosis claimed his life at the mere age of 25, Beardsley managed to carve out an illustrious career that would influence the world of arts and culture far beyond his short life. His monochromatic line drawings were groundbreaking for the era, and the themes of eroticism and immorality both scandalised and titillated Victorian society. Armed with a bizarre sense of humour and a taste for the grotesque, Beardsley came onto the scene like a slow-building storm and ended up leaving chaos in his wake.

Now, nearly a century after the last comprehensive exhibit of his work, Tate Britain is showcasing his unbridled talent once again.

“Beardsley’s style was definitely unique,” says Dr Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, professor of English at Ryerson University and editor of The Yellow Nineties, a database dedicated to research on the avant-garde periodicals of the 1890s. “Even today, his use of line, his massing of positive and negative space, and the ambiguity of the people he drew were striking and seem modern.

“His subject matter was also provocative – his images often portrayed nude and/or grotesque figures that challenged many boundaries of propriety.”

Beardsley was very much obsessed with the macabre and the peculiar. This idea, and the notion that sensitive Victorian values were something to be mocked and satirised, ensured that the illustrator was a character that was both bizarre and gratuitous at the same time. When asked in an interview why he was so drawn to certain themes, he replied “people hate to see their vices depicted [but] vice is terrible, and it should be depicted”.

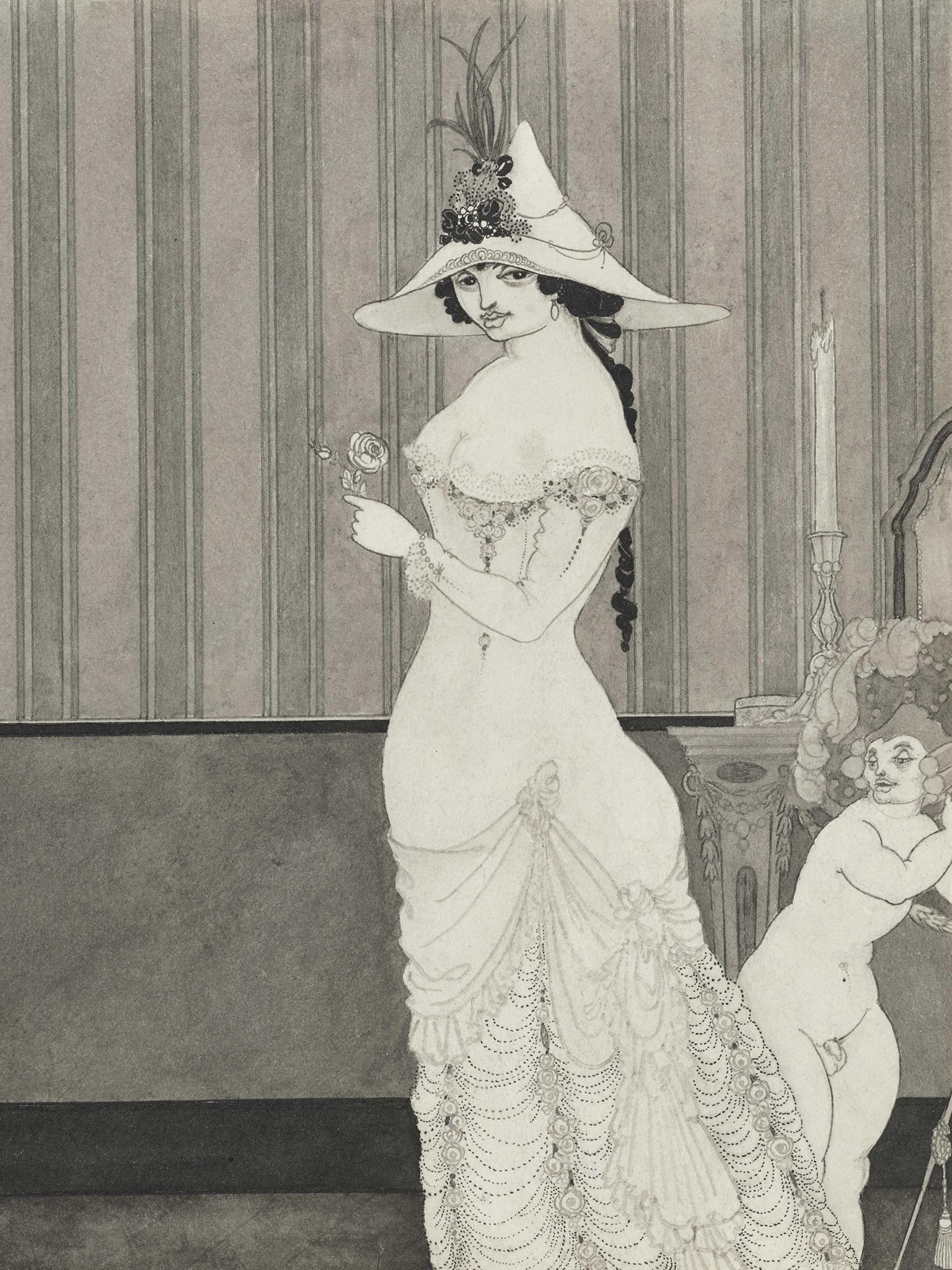

There was also a sort of mad genius to his work and in just six years, the number of styles Beardsley went through was immense. “Beardsley’s most striking aspect was his openness to change,” says Dr Sasha Dovzhyk, an independent curator and researcher at Birkbeck, University of London. “He was constantly reinventing himself. Between 1894 and 1896, he moved from the laconic black-blot technique to the scrumptious excesses of Neo-Rococo compositions.

![When asked why he was drawn to certain themes, Beardsley said: ‘People hate to see their vices depicted [but] vice is terrible, and it should be depicted’](https://static.independent.co.uk/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2020/03/02/22/beardsley-4.jpg)

“This was followed by line drawings reminiscent of classical vase paintings, and this wasn’t even his stop.”

This obsession with the grotesque and an almost frenzied need to make his mark on society, both culturally and artistically, was perhaps the product of a life faced with the constant fear of death. Life was a precarious thing for Beardsley.

The end of the 19th century, dubbed the “Beardsley period” by some of contemporaries, was a time of clashing ideals – between those who wanted to maintain the status quo, adhering to strict Victorian ideals of morality and the fin de siecle (turn of the century) generation who wanted to explore artistic, sexual and political experimentation.

Two particular movements emerged in the final decade, both of which Beardsley found himself one of the defining figures of. Aestheticism embraced the theory of “art for art’s sake”, which espoused that artistic works were a means to explore provocative themes and the pleasure that one could derive from it was to be valued. Decadence, an extension of aestheticism, favoured ideas such as eroticism, morbidity and the fantastical. Both movements conflicted with rigid Victorian values which favoured art which told a moral story.

Besides art, if there ever was an abundant symbol of the fin de siecle, it was the sartorial dandy – and a dandy Beardsley was. The ubiquitous symbol of male fashion became synonymous with the refined gentleman, an individual whose wit and style was an art form in itself. The illustrator was meticulous with his appearance, never seen without a suit, gloves and a morning coat. Even against his gaunt frame – he reportedly used a walking stick – the image that Beardsley cultivated was reminiscent of a self-taught and otherworldly individual – a notion that the illustrator was determined to present to the outside world.

In many ways, he was also a literary artist. He would sometimes read up to three books a day, consumed with the pursuit of knowledge. The fin de siecle were an enlightened bunch, and Beardsley was no exception. He was a child prodigy, gifted with a delightful sense of humour and a penchant for the satirical as well.

Born in Brighton in 1872 to a jeweller and a daughter of an army sergeant, Beardsley’s entry into the world of art began after his family moved to London. While working as an accountant, he met Pre-Raphaelite painter Sir Edward Burne-Jones. It was Burne-Jones, impressed with his talent, who recommended that the young Beardsley attend art school, and helped the illustrator take up art as a profession in 1891.

The first step on the path to notoriety began in 1892 when bookshop owner and photographer Frederick H Evans introduced the young artist to publisher JM Dent. The publisher commissioned him to illustrate Le Morte d’Arthur, a 15th century retelling of the Arthurian legends by author Thomas Malory. At just 20 years old, Beardsley produced hundreds of illustrations for a 12-part edition that was released between 1893 and 1894. For many art historians, Le Morte is considered his first masterpiece, and the first to establish his distinctive style

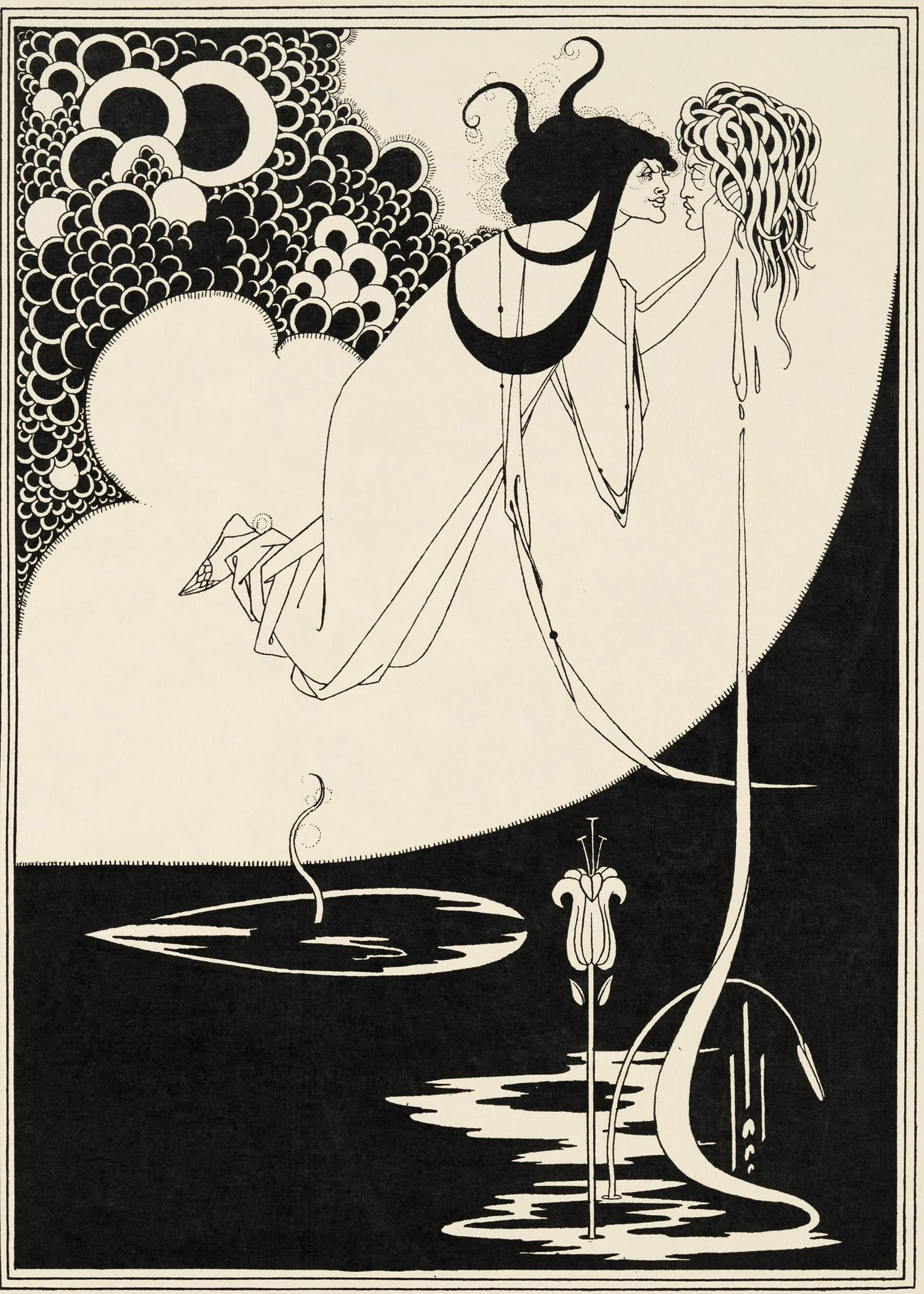

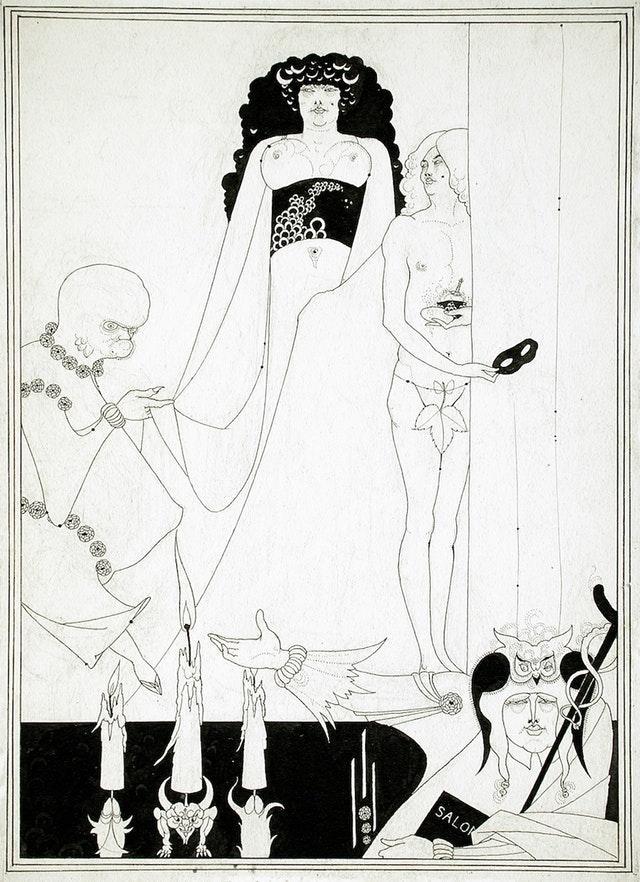

However, Beardsley’s short career became almost legendary following his association with one of the most controversial of art connoisseurs – Oscar Wilde. His decadent lifestyle and outspoken views on fragile Victorian sensibilities ensured Wilde’s reputation, bringing attention to anybody connected to him. The prolific poet and playwright liked a drawing of Beardsley’s that had been rejected and sought his services. This led to publisher John Lane commissioning Beardsley to illustrate the English edition of Wilde’s French tragedy Salome in 1893. The 16 ornate images he produced for the play became the centrepiece of his career and truly cemented the illustrator’s reputation as a genius and maverick at just 21 years of age.

The controversial play, originally in French, tells the story of the titular biblical character who demands (and receives) the severed head of John the Baptist on a platter. The play was rife with eroticism and subtle sexuality and, as a result, was banned from being performed on British stages.

Wilde needed images that conveyed the themes of the work but were respectable enough to find an audience. Beardsley did not do that. What followed were images that were still erotic, but more symbolic than explicit. “Many details that were hidden in plain sight went to print uncensored,” explains Dovzhyk, an independent curator and researcher at Birkbeck, University of London. “For example, the candlesticks in the illustration ‘Enter Herodias’ look innocent at first glance but are, at closer inspection, conspicuously phallic.”

Given Beardsley’s propensity for the grotesque, it is of no surprise that some of the commissions were even more sexualised. One such image, “The Climax”, shows Salome holding the head of John the Baptist – still dripping blood – having just kissed him. Some even show bare-chested women and uncovered genitals.

At the very heart of Beardsley’s work is a desire to satirise and critique the prudish mores of Victorian society. “One of the themes in his work was the idea of the New Women, a notion that was widely debated towards the end of the century,” explains Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, curator of British art at the Tate.

The era of the emancipated woman truly began during the fin de siecle, inspired by the work of first wave feminists who sought to free themselves from the traps of the patriarchy. The New Woman was autonomous, rebellious and sexually independent, Janzen Kooistra asserts, an idea which many decadent artists wanted to explore through creative means.

The women of Beardsley’s work are vivacious. His Salome can be considered a femme fatale, shown to be seeking sexual gratification and often depicted as the seducer of weaker-willed men. Some works show prostitutes and other “sexual deviants”, while other figures hide behind masks, a subtle nod to the exploration of sexuality that was encouraged during the last decade.

Perhaps the most scandalous of all his works was his 1896 illustrations for Lysistrata by Aristophanes, a Greek comedy in which the women of ancient Athens go on a sex strike as a means to force men to end the Peloponnesian war. Although only 100 copies were made and privately distributed among private clientele at the time, the graphic nature of the drawings found a new audience more than six decades later.

“In December 1967, illustrations for Lysistrata were printed in Playboy, epitomising the ‘Art Nouveau Erotica’,” says Dovzhyk. Beardsley’s work was dubbed “a product ‘of covert and perverse preoccupation with sex’ bred by ‘Victorianism’s overt prudery’”.

He was also one of the first artists to depict gender fluidity and same-sex relationships to wider audiences, explains Corbeau-Parsons. Many figures in his work appear androgynous (some more graphically so…), while some art historians have suggested that certain symbols are symbolic of homosexuality – highly illegal the time.

It is important to note that Beardsley’s sexuality has never been confirmed, and there are even some suggestions that the illustrator may have been asexual. Nonetheless, his fascination with the grotesque and the erotic, coupled with his desire to shock, ensured the ideas in his work were nothing but contentious.

His work led to him having an almost mysterious air around him and with this mystery comes scandal and gossip. Society condemnation of his erotic ideas led to constant rumours about his private life. One such vitriolic rumour suggested he was in an incestuous relationship with his sister Mabel and even got her pregnant. In many ways, he was very much an enigma to be scorned.

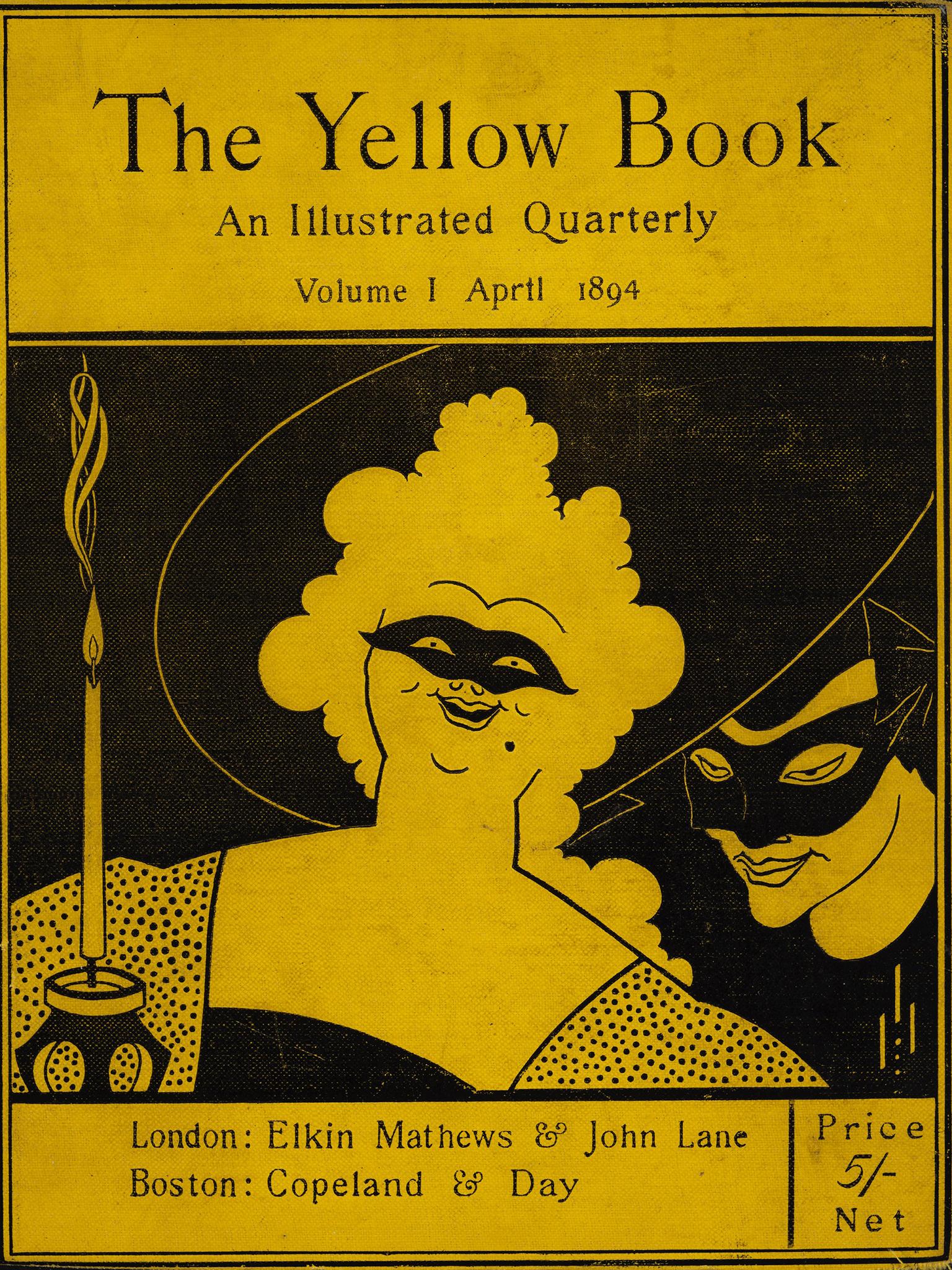

Besides Salome, another publication gained Beardsley an almost frenzied level of notoriety – The Yellow Book. The quintessential magazine of the aesthetic movement was published between 1894 and 1897, of which Beardsley served as the publication’s first arts editor for a year. He brought his distinctive linework to the magazine, drawing in an audience interested in the burgeoning new ways of life.

Beardsley’s distinctive yellow cover design was deliberate. London’s cultural neighbour, Paris, would wrap salacious and controversial novels in yellow paper to alert the reader to its contents, a notion that would have been known to Victorians.

“Its striking yellow boards, distinctive artwork created by Beardsley, and controversial content created a buzz and notoriety within the first year of publication,” Janzen Kooistra explains. Priced at five shillings – £16.55 today – it explored a wide range of literary and artistic genres; it also contained poetry, illustrations and short stories.

The artwork was relatively tame compared to some others works, but fate was about to step in and put Beardsley on a collision course with the infamy he so desired. “The Yellow Book eventually became associated with the tragic story of Wilde,” Janzen Kooistra says. “In 1895, when the playwright was imprisoned for the crime of loving another man, sensationalist headlines claimed that he was holding the magazine when arrested, which significantly increased the former’s notoriety.”

Wilde was carrying a copy of Pierre Louys’ Aphrodite, also bound in yellow paper. The illustrator’s past association with the playwright decimated Beardsley’s career. So scandalised was Victorian society that mobs gathered to throw stones outside publisher John Lane’s London office.

“Six of Lane’s most prominent authors demanded not only that Wilde’s name be expunged from the publisher’s catalogues, but also that Beardsley be utterly disassociated from the magazine,” Janzen Kooistra continues. Fearing further moral panic from conservative individuals, Lane eventually succumbed to pressure and fired the artist from the publication.

Ever one to embrace scandal, Beardsley helped found The Savoy (named after the hotel were Wilde reportedly met his lovers), another literary magazine that was “a manifesto in revolt against Victorian materialism”.

However, despite having such a vibrant and dramatic life, Beardsley was an ill man who was very aware that he was working under the sentence of death. At just seven years old, he contracted tuberculosis, which left his health in a precarious condition for the majority of his short life. He attempted to convince the world that he was a carefree dandy-like figure, but in reality, he was dogged by fears of death.

“Aware that his time was limited, Beardsley was working avidly, with passion and in great haste,” says Dovzhyk. “It is astonishing that he managed to complete more than a thousand designs, not to mention exquisite writing, in a mere six years.

“With the progress of his TB, Beardsley was growing more anxious about finances, failing to keep his miraculous productivity. Still, he was thinking and writing about new projects until the very end.”

The illustrator had a very prophetic view of his illness, once remarking: “I shall not live much longer than did Keats.” The English Romantic poet succumbed to the disease at 25 and, in a tragic turn of events, Beardsley would meet his maker in the same circumstances. The artist moved to France just before the end, where he suffered from a haemorrhage and died in 1898, surrounded by his family. He was reportedly buried with his favourite copy of Alexandre Dumas’ La Dame aux Camelias.

Speaking of his contemporary’s demise, Wilde lamented: “There is something macabre and tragic in the fact that one who added another terror to life should have died at the age of a flower.”

But death was most certainly not the end for Beardsley’s legacy. His unconventional line drawings have lived on in the public consciousness, and he achieved his ultimate aim – to interfere with the very fabric of Victorian society. “His work was circulated far and wide: in international art journals read by Pablo Picasso, Franz Kafka and Paul Klee,” explains Dovzhyk. “He captured the imagination of writers such as Vladimir Nabokov and William Faulkner. He inspired French Symbolists, many Art Nouveau artists and even the Poster Art movement of the 1890s.

“The myth of Beardsley as a Victorian sexual liberator was forged in the Swinging Sixties when he became the subject of a major exhibition at the V&A … he became a cover boy of the sexual revolution (and of a Beatles album).

“You can find the seeds of the 20th century major -isms, in Beardsley’s near-abstract compositions, from Suprematism to Surrealism. More than 120 years after the artist’s death, his work it still surprising, unsettling, and new.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments