Artemis I: Putting humans back on the moon and why it’s taken so long

The last person to walk on our nearest neighbour was 50 years ago. Mick O’Hare looks at why Nasa thinks the time is right again

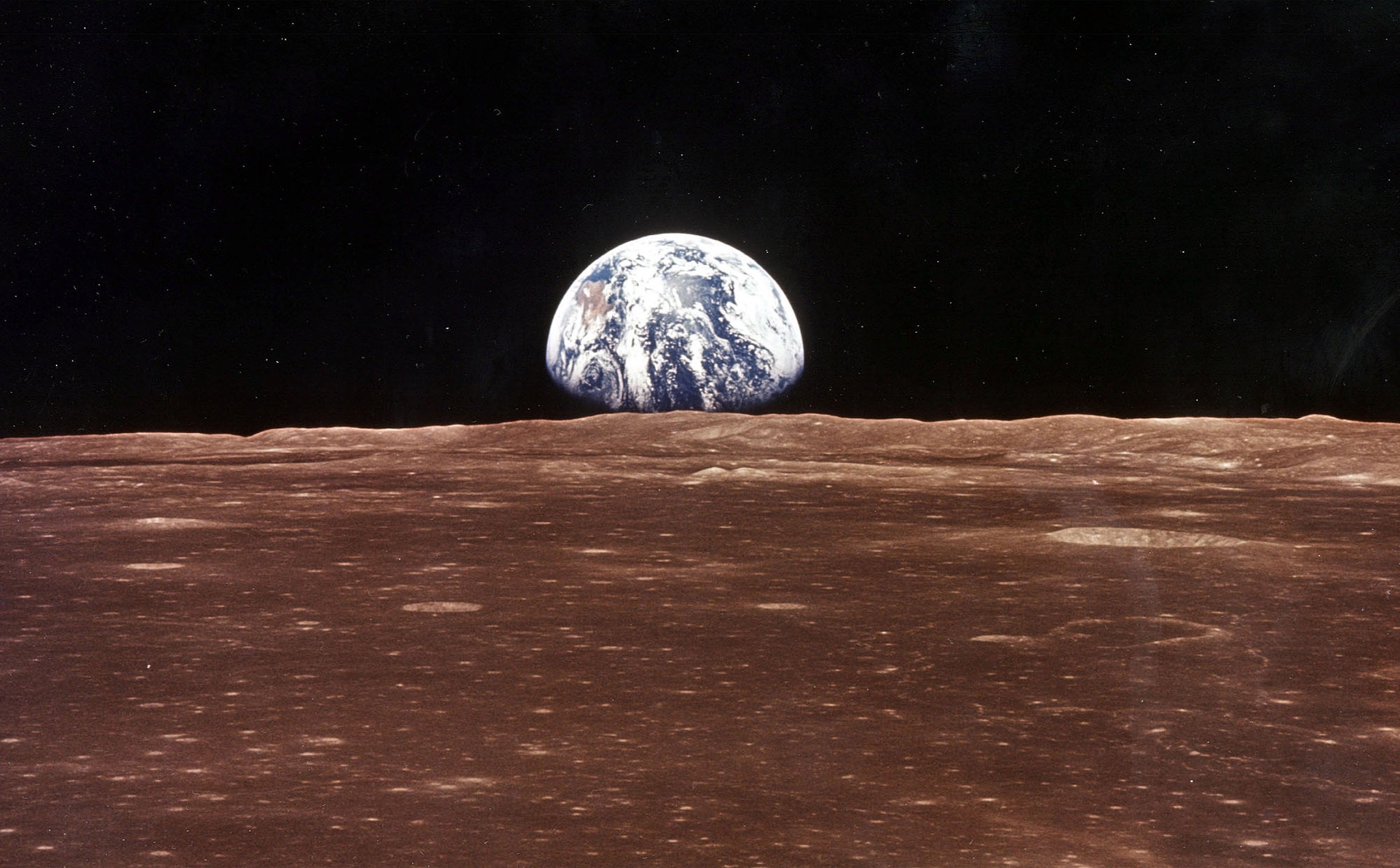

Plenty of people can name the first human to walk on the moon, but how many can name the last? Eugene Cernan stepped off the lunar surface at 17.54EST on 14 December 1972 and climbed the ladder to join his fellow astronaut Harrison “Jack” Schmitt already inside Challenger, Apollo 17’s lunar module. The hatch swung shut behind them. Nobody has walked on the moon since.

Now, it seems, we are returning. Nasa’s Artemis programme aims to put a human on the moon in 2025. For space nuts, it’s exciting times once again. But why has there been a 50-year hiatus (and counting) between Apollo 17 and Artemis? Why was the Apollo programme – one of humanity’s greatest technological achievements whose apotheosis saw Neil Armstrong become the first person to walk on the moon – curtailed? Perhaps more significantly, why has there been no imperative to return in the intervening five decades?

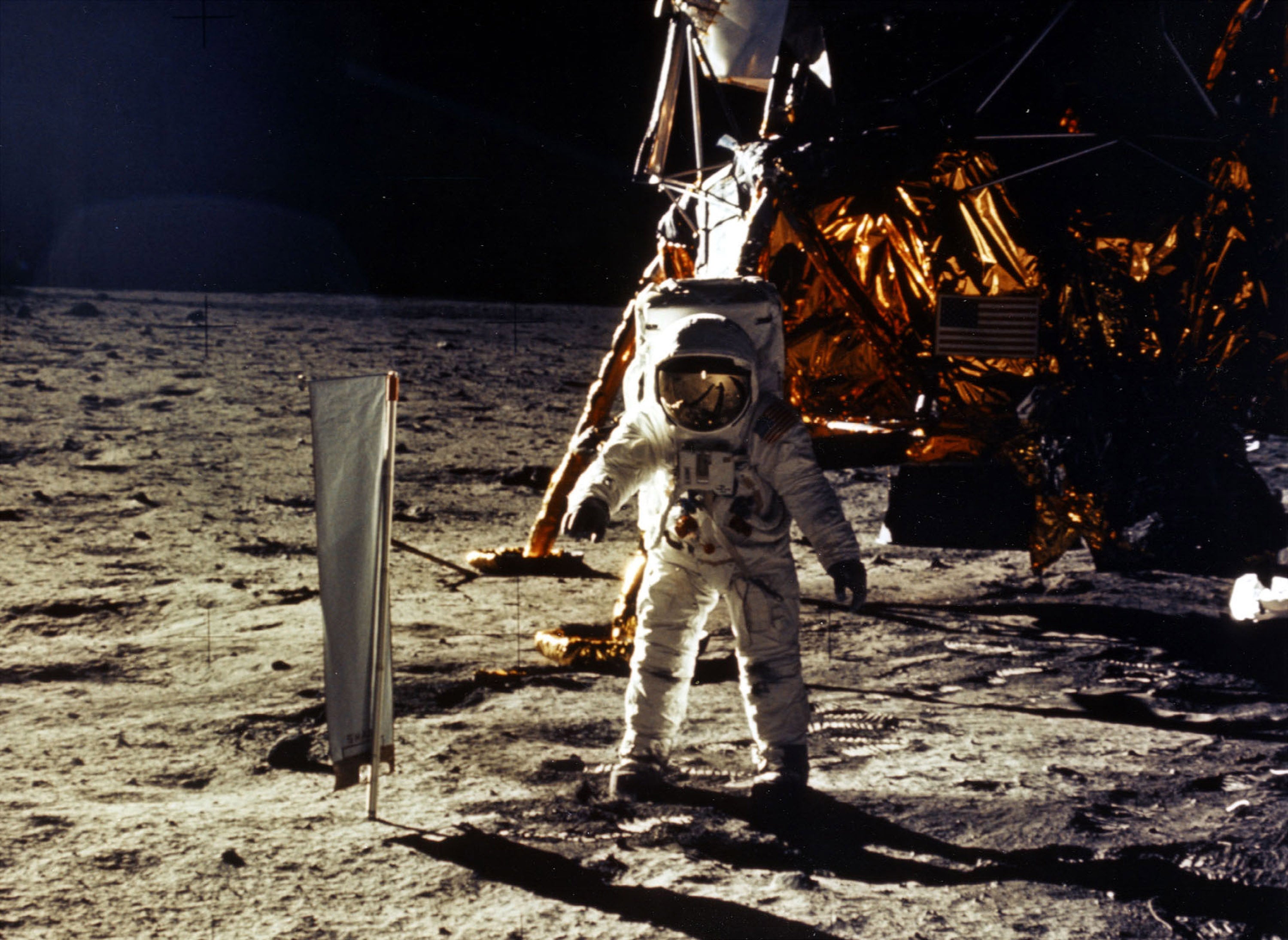

Apollo was a product of its time. And that time was the Cold War as the United States and the Soviet Union vied for the political affections and affiliations of the rest of the planet. In truth, perhaps the most astonishing part of the Apollo story is that the US, having landed Armstrong and his colleague Buzz Aldrin on the moon in Apollo 11 in July 1969, bothered sending anybody else. Another five launches would take 10 more astronauts to our nearest neighbour. To politicians in Congress, these later missions counted for very little. Apollo 11 had achieved its aim: beating the Soviet Union to the moon. Job done.

“Getting to the moon first does not prove your ideology is better but it does impress the international public,” says Teasel Muir-Harmony, curator of the Apollo spacecraft collection at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC. “But once that was achieved, political and public interested waned.”

“It was war by another means,” says Roger Launius, who served as Nasa’s chief historian from 1990 to 2002. “And, with Apollo 11, the US won.” Geopolitical hegemony trumped scientific endeavour.

Certainly, Nasa had a scientific imperative behind Apollo, even if the politicians didn’t, and ambitiously it had hoped the missions after Apollo 11 would spend longer on the moon. It chose sites of scientific and geological interest, planning for the astronauts to travel far from their lunar module base using rovers packed with scientific instrumentation. But to the political class and, increasingly, the American public it all started to look like a waste of time. Even at the height of Apollo mania only 53 per cent of Americans thought it worthwhile. Television viewing figures, which broke all records as Neil Armstrong took his “one small step” into the lunar dust in July 1969, had dwindled to next to nothing by the time Apollo 17 was on its launchpad in late 1972.

By then, the US government had more earthbound issues on its mind and eating up its dollars. The nation’s involvement in the Vietnam War made Apollo seem frivolous. Americans were dying abroad and the public instead saw money being squandered on sending astronauts to walk on the moon. For what? And at home, the civil rights movement was on the march, politically dividing a nation that was still coming to terms with societal divisions that had existed since its formation 200 years earlier. “And of course, there will always be calls for all the money and resources ‘wasted’ on Apollo to be directed towards hospitals, cures for cancer, education, alleviating poverty...” says Muir-Harmony. “So once Apollo 11 had returned successfully, those calls grew louder.”

Also playing on minds was the near tragedy of Apollo 13. Launched in April 1970, the mission was on its way to the moon when an explosion in the service module damaged an oxygen tank rendering the module’s propulsion and life-support systems inoperable. The three astronauts had to transfer to the lunar module – designed for only two – and use its engine to slingshot around the moon to return to Earth. That they were successful was only down to the ingenuity of mission controllers on the ground who overcame numerous life-threatening obstacles to get the astronauts home.

The politicians, especially president Richard Nixon, were spooked. Many of them recalled the Apollo 1 launch pad fire of 1967 which killed three men and seriously dented public enthusiasm for crewed spaceflight. A president could not risk losing Americans in space, it would almost certainly lead to electoral defeat. Support in government ebbed. “The truth is Nixon had associated himself closely with the Apollo astronauts,” says Muir-Harmony. “He felt he was a father figure to them and, for all his failings, he cared deeply about the missions. So on two levels – a personal one, but also a political one – it was unthinkable to him that any of them might die in space.”

All the expertise that was channelled into achieving the moon landings in the 1960s is now simply focused elsewhere

At first, Nasa began to scale back its aspirations, shortening future Apollo missions and limiting their scientific aims. But it wasn’t enough to satisfy those with their hands on the purse strings. Over the course of 1970, Nasa administrator Thomas Paine was forced to cancel three Apollo missions – 18, 19 and 20 would not fly. President Nixon, noting the approaching election of November 1972, also wanted to cancel 15 and 16. He didn’t succeed but Apollo 17 would be the last.

The argument put forward was that American ambitions in space would be better served in Earth orbit. The space station Skylab, which would be launched in 1973, and the forthcoming space shuttle were given priority. Also, the United States had committed itself to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project of 1975, intended to promote detente in space and offer a symbolic end to the US-Soviet “space race”. These projects were also notably cheaper. George Trimble Nasa’s deputy director of manned spaceflight called it “an ill-defined termination” of Apollo. But Apollo was by now considered expensive, difficult and dangerous. And it was not at the top of voters’ priorities.

But it has been 50 years since a human visited the moon. Why has nobody – not only the United States – ever returned? It is not, as you might think, simply a matter of cash. It’s the fact that it is so complicated, so difficult, and all the expertise that was channelled into achieving the moon landings in the 1960s is now simply focussed elsewhere. People lost or failed to renew logistical and engineering capabilities and the science experts slowly died off. Getting to the moon is something that – for Artemis – had to be relearned from scratch. Sending up an uncrewed probe is one thing, putting humans into a spacecraft and depositing them safely on our nearest neighbour is quite another.

The conditions that incubated Apollo just aren’t there anymore, and that’s even if you ignore all the Cold War connotations. “If you assume that once a goal like the moon landings had been achieved it would only get easier, you’d be very wrong,” says Doug Millard senior space curator at London’s Science Museum. “Getting people to the moon was not designed to be repeated.”

Huge investments in time, money and technology took Armstrong to the Sea of Tranquility landing site. Apollo required the biggest rocket ever built (the Saturn V), a huge launch pad and mission control network, complex designs for the command and lunar modules, space suits, heat shields for re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, special nutrition… the list is endless. And you also need the facilities to build and maintain it all. Once you stop going to the moon you don’t need this stuff anymore. The factories close and employees get new jobs or retire. “The United States directly, and indirectly, employed 400,000 people on Apollo. Their jobs and their livelihoods were entwined with the project,” says Muir-Harmony. “When it ended, most moved on. Trying to organise and galvanise such a huge pool of humanity once again would have been a thankless, almost impossible task. And for what? The goal had been achieved.”

So when you decide 10, 20 or – as it turns out – 50 years later that you want to go back to the moon you have to go right back to square one. And because we have new materials, new fuels, new computers, new suits, new spacecraft designs, new everything… all we learned and all we invented and all we used back in the 1960s is pretty much redundant. Apollo had a computer with 64KB of memory – it was state of the art back then but you wouldn’t want it in Artemis.

And, of course, everything needs to be tested repeatedly before you risk putting astronauts aboard. The two space shuttle disasters and the public reaction to them focused minds at Nasa. Losing astronauts, including civilians, was hugely detrimental to the space programme and the reputation of the administration. Even using tried-and-tested equipment, space and the moon are lethal places – in direct sunlight temperatures top 127C, in shade at the moon’s poles they fall to –253C. It costs a lot to keep humans alive and safe up there. Madhu Thangavelu, an aeronautical engineer at the University of Southern California, says: “There is no more environmentally unforgiving or harsher place to live than the moon.”

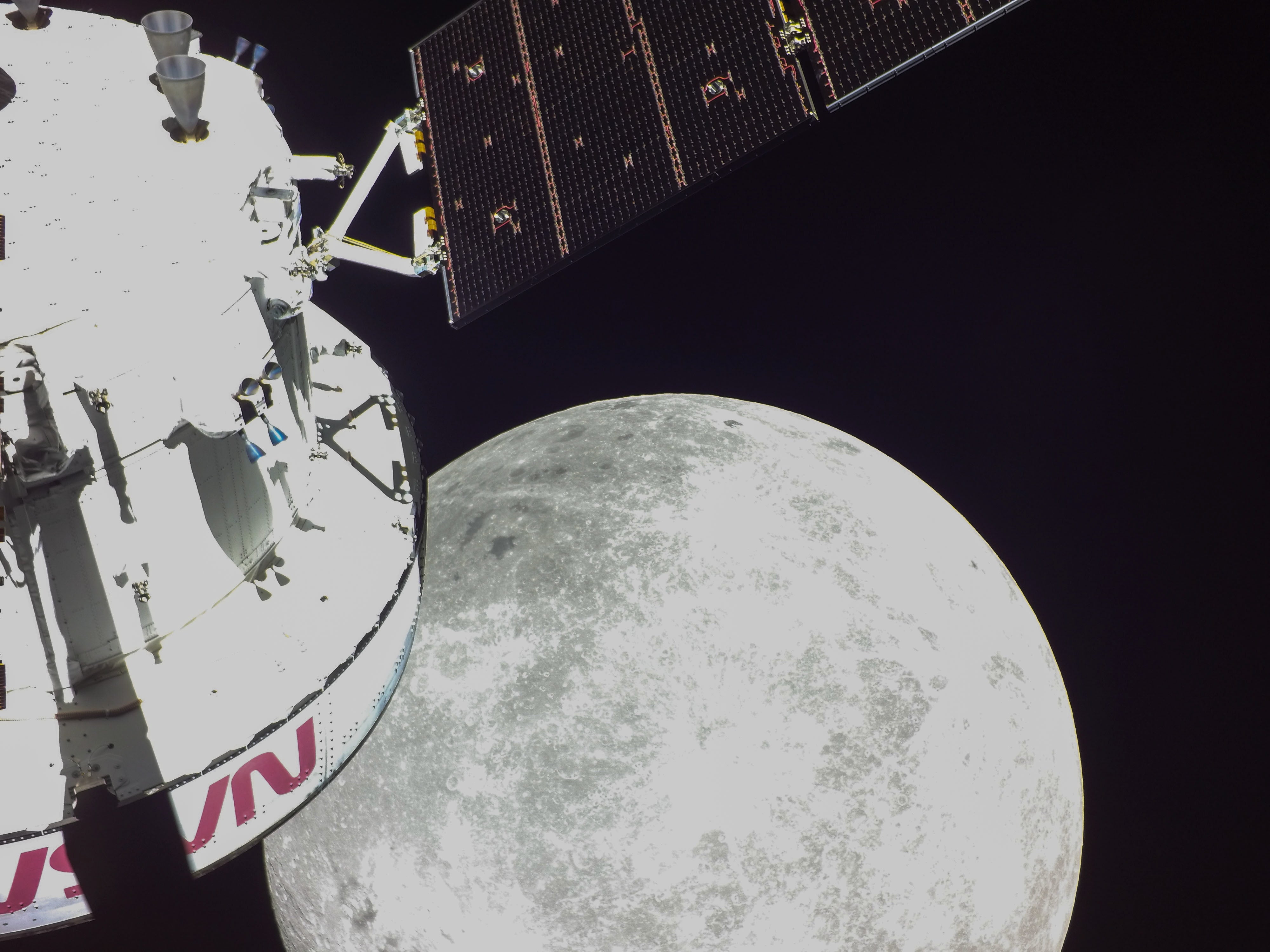

Artemis I launched on 16 November, an uncrewed dry run for the next moon landing powered by Nasa’s Space Launch System

Millard also points out that reproducing the command structure of Nasa to replicate that of the Apollo years would be onerous. “That cohort of American military engineers and technicians was the last generation to live through the Second World War, growing up with a chain of command that lived on in Nasa and drove the Apollo programme. Their aviation and military expertise – necessary for success – would be so difficult to replicate without very good reason.”

It’s not only the hardware and those building and directing it that have changed significantly, it’s the mission’s aims too. A significant proportion of the public could see why their taxes were being used to fund Apollo – the Cold War played a huge role in the life of nearly everybody on the planet. But today? A moon-landing programme would have to prove it could hugely benefit society before it would have widescale approval.

That’s why it has taken so long between the death of Apollo and the birth of Artemis. And even then it has required private finance – think of the likes of Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin – to fill the rather large gap between national aspiration and taxpayer blessing. “Private enterprise is where the future of moon exploration lies,” says Apollo 17’s Schmitt. Former Nasa deputy administrator Lori Garver says “Apollo was a combination of fear and glory. I think today’s renaissance is about greed, and I’m fine with that.”

Whether the moon will yield commercial benefits is yet to be established, but plenty of people are prepared to try and find out. Others see the moon as merely a stepping stone on the way to the riches that Mars might hold – establishing a crewed base on the moon would open up plenty of similar opportunities. “It’s a logical step,” says Jim Bridenstine, Nasa administrator between 2018 and 2021.

And as nations from China to Japan to India to Brazil start to make their mark in space, the US, one-time victor of the space race, doesn’t want to be seen to be lagging. Where once the partisanship of politics led to governments and presidents proposing new moonshots, only for the opposition to win power and immediately cancel the “foolhardy and expensive pipe dreams” of the previous incumbent, now success in space has once again become an issue. “Budgets change, administrations change and priorities change,” says Bridenstine. Pride, it seems, still has its part to play. Garver may have been wrong when she said it was all about greed.

By the time Cernan climbed into Challenger, moonwalking had become prosaic. The intervening 50 years haven’t been kind to those eager to push the human boundaries of spaceflight. The planet’s population simply doesn’t hang eagerly on every new flight to the International Space Station, or every new launch of yet another remote-controlled Mars lander.

Artemis I launched on 16 November, an uncrewed dry run for the next moon landing powered by Nasa’s Space Launch System, the biggest and fastest rocket ever built, surpassing even the Saturn V. It will carry, in its Orion crew module, people further into the solar system than ever before. It will also, if all goes to plan, land humans – including the first woman and first person of colour – on the moon as soon as 2025. Currently, only 12 people – all of them white men – have ever visited our nearest neighbour.

Maybe Artemis will reinvigorate humanity’s interest in what is out there. But at the moment, public enthusiasm for the programme is noticeably lacking – only 38 per cent of Americans think Artemis should proceed while 91 per cent think Nasa should focus on spotting killer asteroids – but perhaps the sight of a human on another world will change that. “Most of the United States has not been paying attention to Nasa’s plans,” says Laura Forczyk, founder of the space analysis firm Astralytica. “But watching a person actually walking on alien soil will, I’m sure, change a lot of minds.”

As Eugene Cernan knew only too well, the human factor makes a big difference. Send a robot into space and the world barely raises an eyebrow, but putting a human onto the moon or maybe Mars? Then you’ve got a story to tell. Judging by his final words from Apollo 17’s landing site at Taurus-Littrow, it’s clear Cernan did not expect half a century to pass before humans returned. He predicted that it would “not be too long into the future”. He also expected humans to have landed on Mars by the end of the 20th century.

One day, however, Cernan’s “record” as the last person on the moon will be expunged. There can only be one first man on the moon – Neil Armstrong’s place in history is assured – but “last man” is a moveable goalpost. Eugene Cernan’s name will eventually be replaced. By the time the 60th anniversary of Apollo 17 rolls around it seems more certain than ever that we’ll be looking at a new “last human”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments