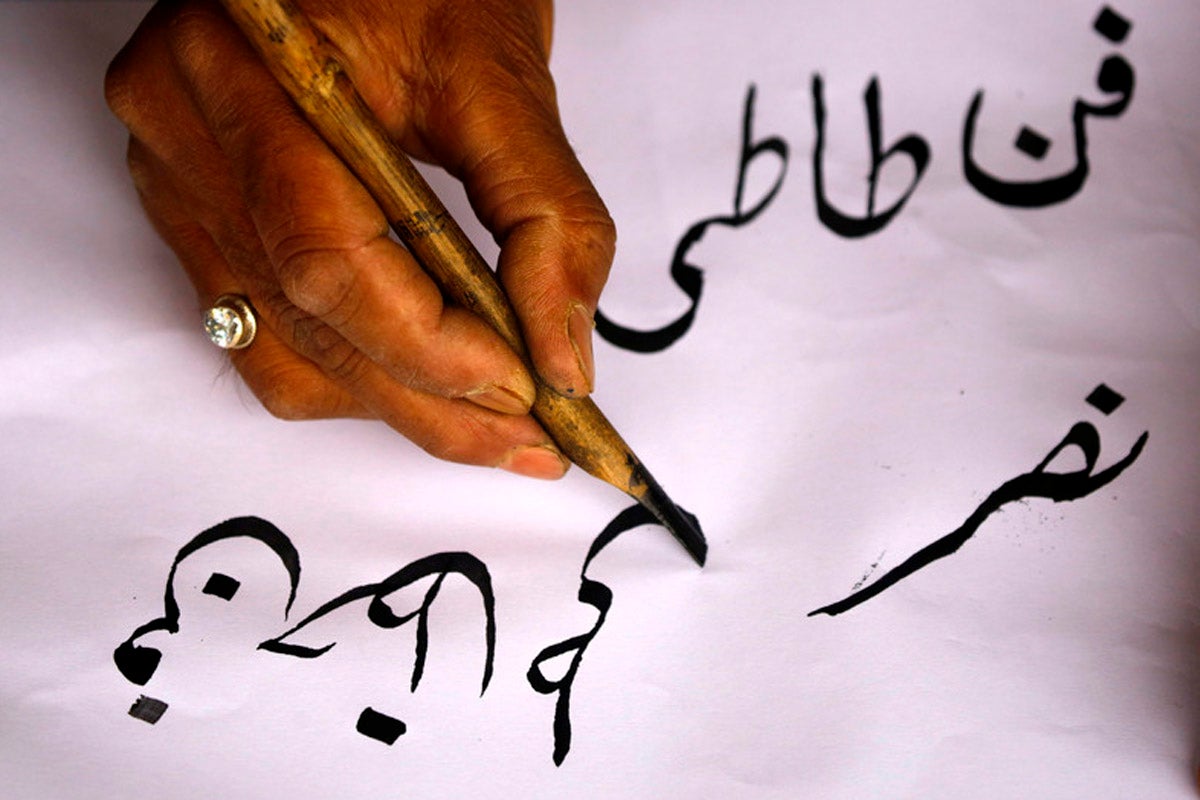

The beauty, art and tradition of Arabic calligraphy

Calligraphy is one of the world’s oldest artforms, but in the Islamic world it remains as vibrant as ever. Now more than ever it’s being used to commemorate the dead. Ahmed Twaij traces its history

Meandering through the eerily quiet and narrow sand paths of Wadi al-Salam, lined on either side with graves speckled to the horizon and beyond, you’ll see colourful Arabic calligraphy adorning the headstones of those laid to rest here. Wadi al-Salam, or the Valley of Peace, located in the southern Iraqi city of Najaf, is the world’s largest graveyard and has become a sombre home for the traditional Islamic artform of Arabic calligraphy, which is used across the Islamic world as a way to honour the dead.

“There is a link between artform, beauty and the afterlife,” explains contemporary Arabic calligraphy artist Ghaleb Hawila. “Customarily, it is seen as an honour to have a calligrapher write your name on your grave.”

Not only is it used to commemorate the dead, calligraphy has become synonymous with Islamic art, with the cursive text appearing across architecture and coin design, on clothing and ornaments. But how the artform came to be actually stems from efforts by Muslims to distance themselves from pre-Islamic Arabia’s idolatrous past.

“The ban on figuration [by Islam] and favouring of abstraction in Arab culture, that was heavily influenced by Islam, has meant that for a few centuries Arabic calligraphers have been repeating the artform, creating very strict canons and so, as a classical art, it is quite structured,” says Yazan Halwani, a Lebanese Arabic calligraphy and graffiti artist. “A lot of refinements have happened over hundreds of years and like any skill that develops there is a kind of Darwinian evolution where it becomes very good over time.” The cultivated nature of the artform led to Pablo Picasso, who paved the way for abstractionism in the west, to be quoted as saying: “If I had known there was such a thing as Islamic calligraphy, I would never have started to paint. I have strived to reach the highest levels of artistic mastery, but I found that Islamic calligraphy was there ages before I was.”

In contrast to the Arab prohibition of figuration, western culture has often celebrated figuration in art. In western society the deceased have historically been honoured through portraiture, statues or busts. At funerals it is commonplace to have a photograph of the departed placed beside their coffin. Similarly, “in ancient Egypt, the wealthier you are, the better mummification and sarcophagus you get”, explains Halwani. “In Islamic times, with the ban on iconography and the representation of the dead, Islam created an environment and culture where you have abstraction only, so people took the writing and geometric patterns and started developing them.”

In Arab culture, there is a saying that goes: “Purity of writing is purity of the soul.” The dawn of Arabic calligraphy was instigated by the creative genius of three master calligraphers from Baghdad: Ibn Muqla of the Abbasid court (886-940), Ibn al-Bawwab the Illuminator (961-1022) and Yaqut al-Musta’simi, secretary to the last Abbasid caliph (died 1298). Though to many, Ibn Muqla is the father of the artform, developing six distinct scripts, known as the “six pens”, which modern day calligraphers master during the process of learning their craft.

Over the years, Arabic calligraphy has developed strict rules whereby each letter is geometrically designed and, at their root, can be broken down into a series of structured dots. As an example, elif – the first letter in the Arabic alphabet – should be one dot wide and three dots in length in Thuluth font. “It’s a bunch of curves,” Halwani says, and it’s true. But what’s exciting about a bunch of curves? “Due to the refinement and sedimentation of different experiences, you get a curve that, when you just look at it, is just so charming.” The strict, rule-based nature of the artform may take away from the individuality of the deceased, and, as Halwani describes, may not “represent the identities of that person”, but instead becomes “an abstraction of their existence”.

Before Islam, the Arab peninsula was renowned for spoken word poetry and little was maintained in the written form. However, to preserve Islam’s holy scripture, calligraphy began to develop in the years following Prophet Muhammad’s demise. Arabs were famous for oral narration, with many proud of their ability to memorise whole poems and verses from the Quran. Some of the earliest documented calligraphic works in the Arab world, however, were the seven Mu'allaqat from pre-Islamic Arabia, a group of seven poems by separate poets hanging off the Kaaba, which later became Islam’s holiest site. “I wonder if the Mu’allaqat were something to honour the poem or the poets that wrote them?” asks Halwani.

The computer engineering graduate from Beirut does not consider himself to be an emotional artist, yet he is responsible for works that have formed an integral part of Beirut’s character; his magnificent murals embellish some of the city’s most iconic buildings. His most recent work, “The Memory Tree”, revealed in July 2018, is a sculpture found in the city centre to commemorate a century since the Great Famine of Mount Lebanon left over 200,000 dead from starvation.

The leaves of the tree bear quotes from people who during the famine. The calligraphy produces a “very aesthetic layer at the top, that creates a love at first sight between the passerby and the artwork”, says Halwani. “So that they can more easily stomach the memorial of the death of hundreds of thousands of people.” With nobody living to tell the story of the famine, Halwani’s use of a tree with calligraphy represents the flora, which could metaphorically have lived through the event, memorialising the narrative of the deceased through the splendour of cursive lettering.

Similarly, Halwani’s portraits, spread across Beirut, also use Arabic calligraphy “as pixels” to commemorate some of Lebanon’s most iconic historical and cultural figures, directly questioning the ban on figuration in Arab culture juxtaposed with the cultural use of calligraphy. Referring to the thousands of political posters sprawled across Lebanon’s urban space, Halwani explains: “I wanted to do portraiture to oppose the divisive political posters.” Images of famous deceased Lebanese artists and poets, who are loved by many across Lebanon, such as Sabah and Khalil Gibran, create “artwork that is representative of people that live within the neighbourhoods and not of the minority of sectarian political parties that try to impose their presence through those posters”.

Arabic calligraphy has instilled itself within the daily lifestyle of Arabs across the globe and has formed the backbone of both contemporary Arab art and commerce. To celebrate the global reach of Arabic calligraphy and its role in everyday life, the Instagram account @arabictypography was created, posting images of Arabic script found around the world, from glorious murals decorating the sides of buildings to subtly elegant script found on the backs of trains or cars. The page has contributors from around the world, using #foundkhtt – khtt is Arabic for handwriting – in the hope of being featured. Last year, the account took a solemn turn.

Calligraphy is our heritage, our artform. We cannot rely on the west to spread our narrative, but it is our responsibility to create media and content

Honouring the tradition of using Arabic calligraphy to memorialise the dead, the account, with over 115,000 followers, has commissioned artists from around the world to design the names of each of the 51 people killed in last year’s New Zealand terror attack. The atrocity in two local mosques in Christchurch sent shockwaves around the world. The largest mass killing in New Zealand in modern history left 51 dead but thousands more grieving globally. At the time, mourning the fallen took many forms, from ceremonial Haka performances by New Zealand’s indigenous Maori community to candlelit vigils around the world.

The campaign was an effort to take ownership of the trauma by remembering the fallen through an Islamic artistic lens. “Since I have this platform I tried to bring together the art community to remember the names of the victims,” says Fatima Moussa, originally from Mauritania and founder of the Instagram account. “The reception has been great,” with some images receiving over 2,000 likes.

“My aim [for the campaign] was to bring back the discussion to the people instead of the white supremacist and to humanise these fallen faces in the process,” explains Moussa. Referring to the numerous articles written about the attacker and some headlines alluding to his past as an “angelic boy”, Moussa says: “We live in a world where we default to centring white bodies, even when they are the perpetrators of the crime.”

Moussa also uses the platform to counter Islamophobia among a wider audience. “Calligraphy is our heritage, our artform,” she says. “We cannot rely on the west to spread our narrative, but it is our responsibility to create media and content.” In the immediate aftermath of the New Zealand attack, a near 600 per cent rise in Islamophobic incidents in the UK were reported by independent monitoring group Tell Mama. Moussa says: “We are trying to use our platform to counter the online islamophobia that resulted in the killings to begin with.”

To this day, within Arab countries, as loved ones pass away, posters with Islamic calligraphy known as warakat al-rawi (The Papers of the Narrator), are produced by bereaved families to announce the passing to their local community. They do this because, Halwani says, “the aesthetic gives a sense of grandeur to the person that died. It honours them.”

The more prestigious the deceased individual is, the more their grave is embellished, using other artforms such as architecture, geometry and symmetry. Examples include the grandiose shrines of the Mughal empire, the Taj Mahal in India or Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib’s shrine in Najaf, each adorned with cursive Arabic calligraphy and architectural geometry and symmetry. Constructed in 977AD, Imam Ali’s shrine, the burial place of Prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law, stands tall in Najaf with symmetrical arches, tiled with blue, green and yellow mosaics decorated with Arabic calligraphy, that hold up a glorious golden dome, paying homage to the role he played in early Islam.

Having spent time as a journalist in Iraq, I witnessed first-hand the harrowing 2016 Karrada bombing in Baghdad, which left over 300 civilians killed. Within days of the incident, the buildings at the site of the attack were draped with posters of Arabic calligraphy, displaying the names of the dead, helping their loved ones grieve while fostering a sombre aura across the city; a perennial reminder of the catastrophe. “With the feeling of guilt when someone in your family dies, you want to honour them as much as possible,” says Halwani. “You use Arabic calligraphy because it is the only artform that is available for you to honour them.”

Halwani adds: “It always goes back to appealing to people at a very visceral level that I cannot explain. It just appeals so much to people that they think it is befitting to honour the dead. I never thought about it this way, but it seems to just resonate with people.”

Walking through Wadi al-Salam, after understanding the years of history enshrined with each brushstroke of Arabic calligraphy on the headstones, you start to comprehend the honour each family has consigned to their loved ones.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments