Twentieth anniversary of 9/11: Counter-terrorist campaigns are more destructive than terrorism

What began in Afghanistan and Iraq as an American-led invasion to overthrow unpopular rulers swiftly transmuted into something closely akin to an old-fashioned colonial occupation, writes Patrick Cockburn

Certain viruses attack the human body indirectly by provoking a self-destructive overreaction by the body’s immune system. Successful terrorists operate in much the same way. They provoke a counterterrorism response out of all proportion to the original attack, and it is this that inflicts the real damage on the target.

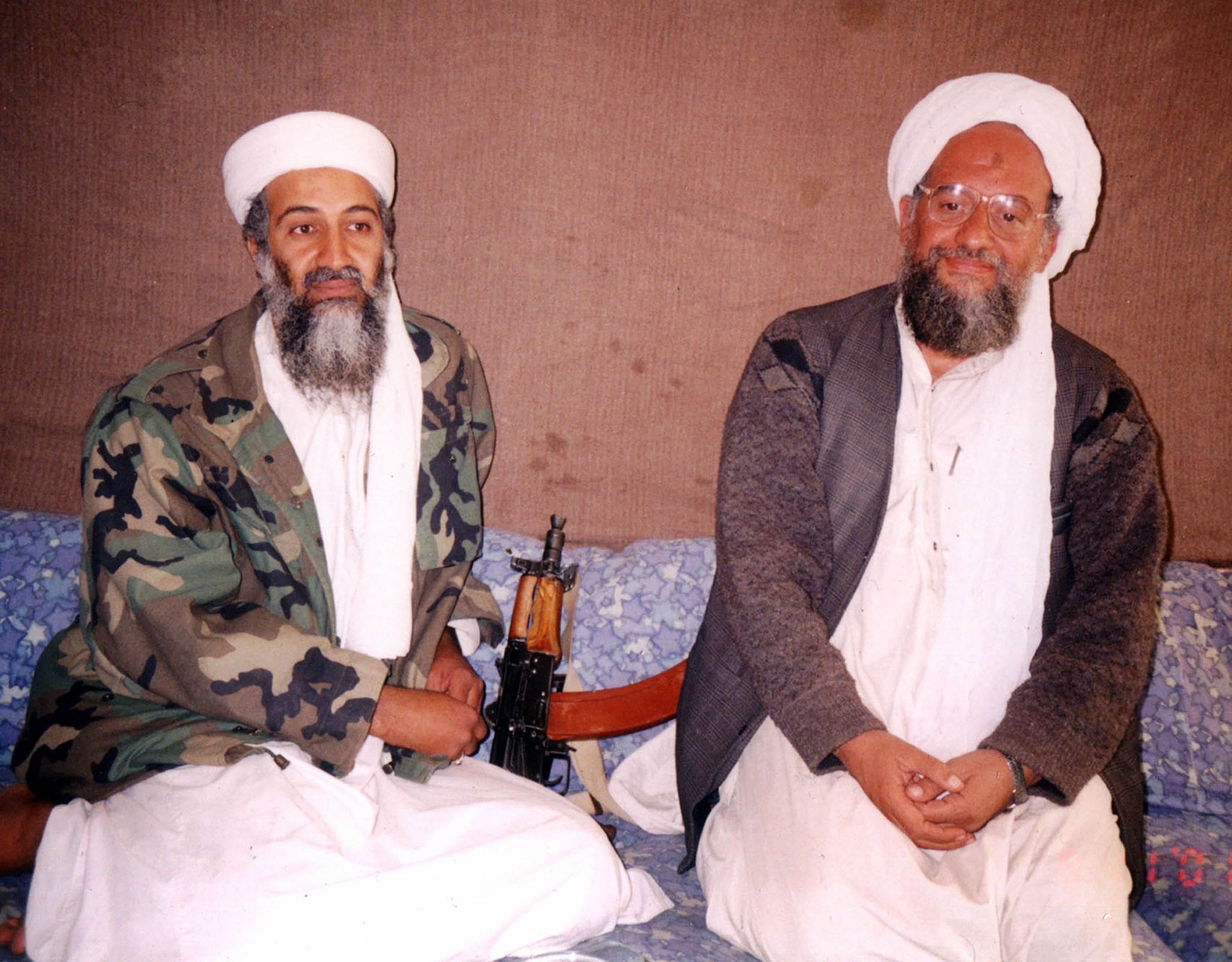

By their very nature, non-state groups using “terrorism” as their prime weapon are small and have limited resources. At the time of 9/11, 20 years ago, al-Qaeda, the most famous terrorist group the world has ever seen, probably had fewer than a thousand activists in Afghanistan and supported a loose network of militants across the rest of the world. The destruction of the Twin Towers gave a tremendous shock to America, but al-Qaeda could never make another attack like it.

Devastating though 9/11 certainly was, its real success was in provoking a counterterrorist campaign that is still ongoing and has done damage to the US at every level. America has been damaged as a superpower because it failed to win wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It has been diminished as a civilised society because it resorted to rendition, torture and imprisonment without trial, justifying illegal actions by pretending that only by such means could public safety be assured.

Osama bin Laden did not show demonic cunning in laying a trap for the US when he and his lieutenants planned and carried out 9/11. They did want to bring the US to battle in the Muslim world, and in this, they succeeded beyond their most ambitious dreams.

In this analysis, “terrorist” and “terrorism” – words that once meant something but have been devalued until they have become crude words of abuse – have a more precise meaning. One man’s terrorist is notoriously another man’s freedom fighter. Authoritarian governments in countries such as Turkey and Egypt denounce and punish anybody opposing their regimes as terrorists.

“Terrorism” in its non-state variant is an act of violence, usually an assassination or a bomb attack, aimed at shaking the established order. It is primarily the weapon of small movements with a core of activists fighting a powerful government. Through what was once called “the propaganda of the deed”, the terrorist stages a spectacular show of defiance against the powers that be and exposes their weakness.

But, unbeknown to many of its perpetrators, terrorism only really generates revolutionary change when it can frighten or tempt the powers that be to overreact. Governments do just that because the public expects action when it is menaced, and governments see that they have been handed an excuse to extend their own authority. Political leaders launch counterterrorism campaigns, posing as the defenders of little house on the prairie and pillorying opponents who call for a more measured response as unpatriotic or treacherous. The full might of the state is exerted to stamp out the terrorist minnow, thereby discrediting and upending the status quo.

This pattern has repeated itself over the last 150 years. The assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914 might have been only a blip in history if the Austro-Hungarian government in Vienna had not foolishly used it to blunder into a war that was to destroy their empire within four years.

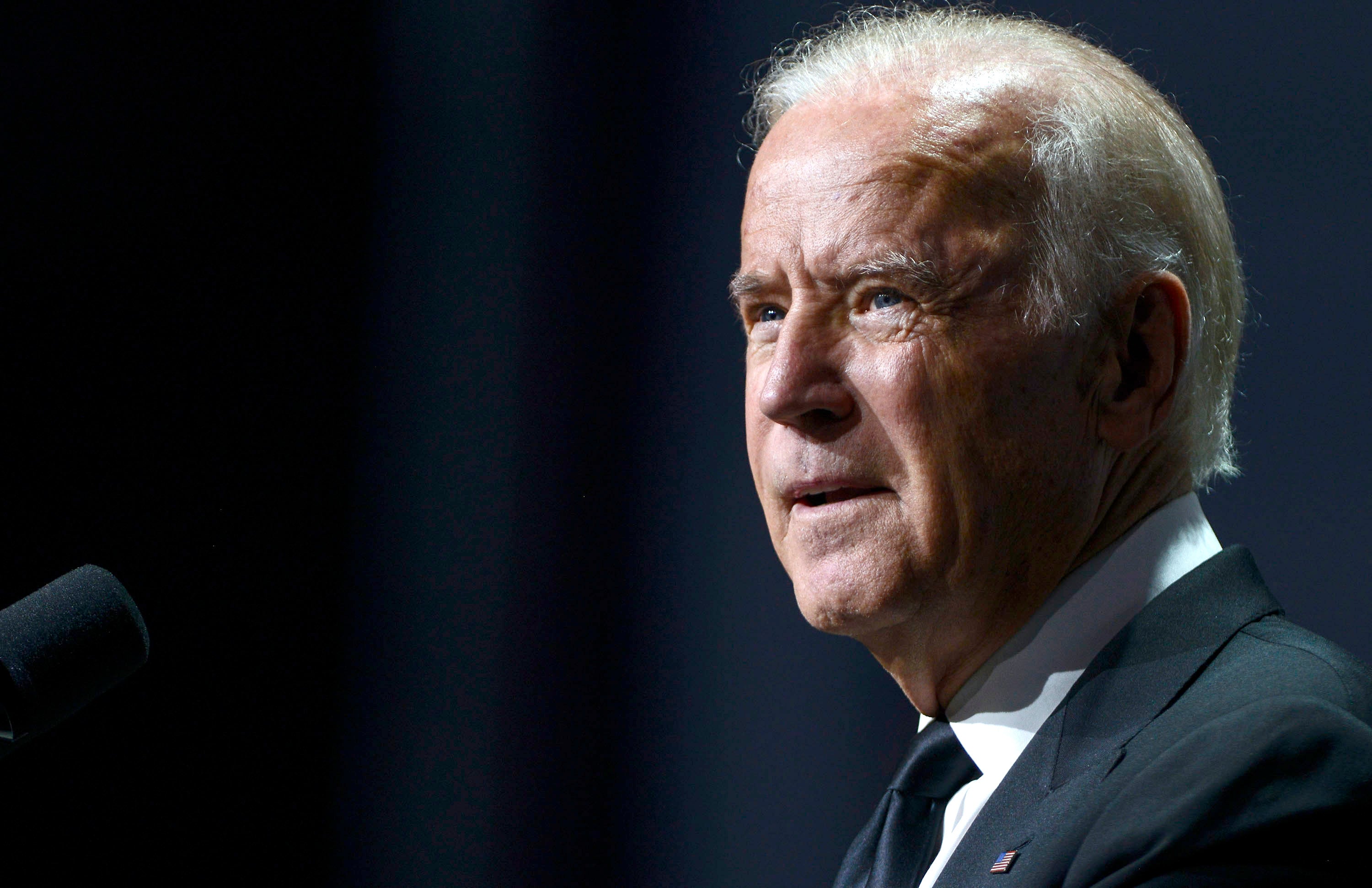

Biden was declaring that ‘the war on terror’ will continue, despite its counterproductive failure over the last two decades

Yet, it is not only political idiots who fall into the counterterrorism trap. The Troubles in Northern Ireland began in 1968 as a demand by the nationalist/Catholic minority for civil and economic rights, but the British and unionist governments treated this as a revolutionary demand threatening the state itself. Sporadic shootings and bombings provoked the collective punishment of minority communities. Repression by the British army led to the swift rise of the Provisional IRA, which became expert at prodding the authorities into delegitimising themselves through excessive violence. Internment and Bloody Sunday were the recruiting sergeants of the IRA. A counterterrorist apparatus was created that always claimed to be on the verge of a final victory that nevertheless remained elusive.

In the wake of 9/11, president George W Bush and prime minister Tony Blair launched a wide-ranging “war against terror”. The targets were broad enough to justify military action against anybody, notably Saddam Hussein, who had nothing to do with 9/11. In the past few weeks, the last few battered chickens who were first launched into the air by this policy have been coming home to roost. Bush and Blair show no sign of understanding where they went wrong and how they played into the hands of Bin Laden. US generals, who failed to defeat the Taliban over 20 years despite commanding 100,000 American troops in the country, denounce the military withdrawal announced by Donald Trump and Joe Biden, but without proposing a feasible alternative policy.

Biden had long criticised the US intervention in Afghanistan as going nowhere, but as the last American soldier climbed onto a plane at Kabul airport, he too was pledging to pursue Isis-K, whose suicide bomber had killed 13 US troops along with some 180 Afghan civilians. Less publicised was the fact that many of the dead civilians were killed by retaliatory gunfire from panicky US soldiers or Afghan special forces defending the airport, according to local eyewitnesses.

In other words, Biden was declaring that “the war on terror” will continue, despite its counterproductive failure over the last two decades. This will be good news for Isis-K, a small group with between 1,500 and 2,200 fighters, according to a UN report. By means of a single suicide bombing, it is being taken seriously as a player, helping it find recruits and raise money as the true defenders of the Islamic faith.

I witnessed the same thing happening 20 years ago when the Taliban lost power in 2001-02. They had not been decisively defeated on the battlefield, but they faced insuperable odds and had lost the war. They might never have been heard of again if the US, in the full flow of its apparent victory, had not demanded their unconditional surrender and continued to harry them.

So convenient – and apparently successful – was the war on terror in terms of domestic American politics that Washington continued to fight it even when there were no enemies left in Afghanistan, the Taliban had disintegrated and what was left of al-Qaeda had fled to Pakistan. The US restored the old warlord, formerly the anti-Communist mujahideen seen as violent gangsters by much of the population, who had fought a ferocious civil war between 1992 and 1996. It was their savage crimes at that time that led to the rise of the Taliban and its speedy takeover of much of the country. By bringing back the warlords after 2001, the US allowed the Taliban to rise again.

The return of the Taliban to power in Kabul will be highly influential in showing the power of fundamentalist Sunni Islam to withstand and defeat powerful enemies

The lesson of the war on terror is that terrorist movements such as al-Qaeda or Isis in Iraq and Syria can be defeated once they become visible. But a counterterrorist campaign poses a far more dangerous threat to stability because governments, armies and security services benefit from their existence and do not want to close them down. They help persuade the public that it is threatened by dark forces it cannot see and which can only be fought by torture, imprisonment without trial and restrictions on legal rights and civil liberties. Whatever atrocities are committed in Guantanamo in Cuba, Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan or Abu Ghraib in Iraq are all a necessary part of being “tough on terrorism”.

The military tactics of counterterrorism serve to spread sympathy for those against whom it is supposedly directed. Military action is commonly conducted by local proxies and by airstrikes and drones. Claims of precise targeting are invariably shown to be false when tested by on-the-ground witnesses. “Night raids” by special assault groups are viewed by villagers in Afghanistan – and most Afghans live in villages – as no better than the arbitrary operations of death squads. Aside from these, the US way of war in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan was to rely on air attacks called in by ground forces.

But, for all the claims of precise accuracy, airpower is the bluntest of instruments, dependent as it is on dubious and uncheckable intelligence that frequently turns out to be mistaken or partisan. In one town south of Mosul in Iraq, for instance, the US claimed that its attacks had killed only one civilian, but an on-the-ground investigation revealed that the true figure was 43 civilians dead, of whom 16 were children. Among the main reasons cited by Taliban fighters for their joining the movement is anger at the civilian loss of life. Any attempt by the US to pursue Isis-K by drones and raids, as promised by Biden, is likely to be as blood-soaked and ineffective as in the past.

Proponents of foreign intervention in the Middle East stubbornly reject the lessons of previous failures, or even acknowledge that anything had gone very wrong. It is widely argued that the US would have succeeded in Afghanistan had its attention not been diverted by the invasion of Iraq in 2003. In reality, the presence of US military forces was often the root cause of local insurgencies through their night raids and airstrikes. Those targeted were often personal enemies, business rivals and tribes hostile to warlords close to the US who identified them as Taliban or al-Qaeda.

What began in Afghanistan and Iraq as an American-led invasion to overthrow unpopular rulers swiftly transmuted into something closely akin to an old-fashioned colonial occupation. “Nation-building” was always a PR ploy to justify the actions of the occupiers. Such propaganda might be taken seriously abroad, but not by those who saw the western presence as alien, while the Taliban were at least authentically Afghan.

Much anguished debate has focused since the fall of Kabul on 15 August on the danger of Afghanistan once again becoming a haven for terrorists, as it was said to have been before 9/11. This was always exaggerated: a guerrilla-type organisation does not require its own mini-Pentagon hidden in the Hindu Kush mountains. The logistical needs of a group like Isis-K are small and it would be unwise to keep its headquarters in one place.

It is much in the Taliban’s interests not to host a group like Isis-K at a time when the new Afghan regime is in desperate need of aid and wants recognition from the west as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. It has been fighting Isis-K since 2015 and wants to present itself as a reliable ally against Isis-K, which is a shrunken force compared with what it was five years ago.

Yet, in a broader sense, the return of the Taliban to power in Kabul will be highly influential in showing the power of fundamentalist Sunni Islam to withstand and defeat powerful enemies. The most sustained counterterrorism campaign in history has been defeated against all the odds. This is the message that will resonate in Muslim communities across the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments