Bye, bye Angela: the European leader bids a fond farewell to the west

Angela Merkel visits Washington today as part of her ‘farewell tour’ ... and by the end of the year, Germany will have a new chancellor. Mary Dejevsky on her life and legacy

With her visit to the White House today Angela Merkel is well on the way to completing what amounts to a farewell tour of the western world. In mid-June, she was in Cornwall for the G7 summit of the world’s richest countries. Ten days on, she bade farewell to Nato and the EU at its last summit of the season, and a week later she lunched with Boris Johnson at Chequers before tea with the Queen at Windsor Castle.

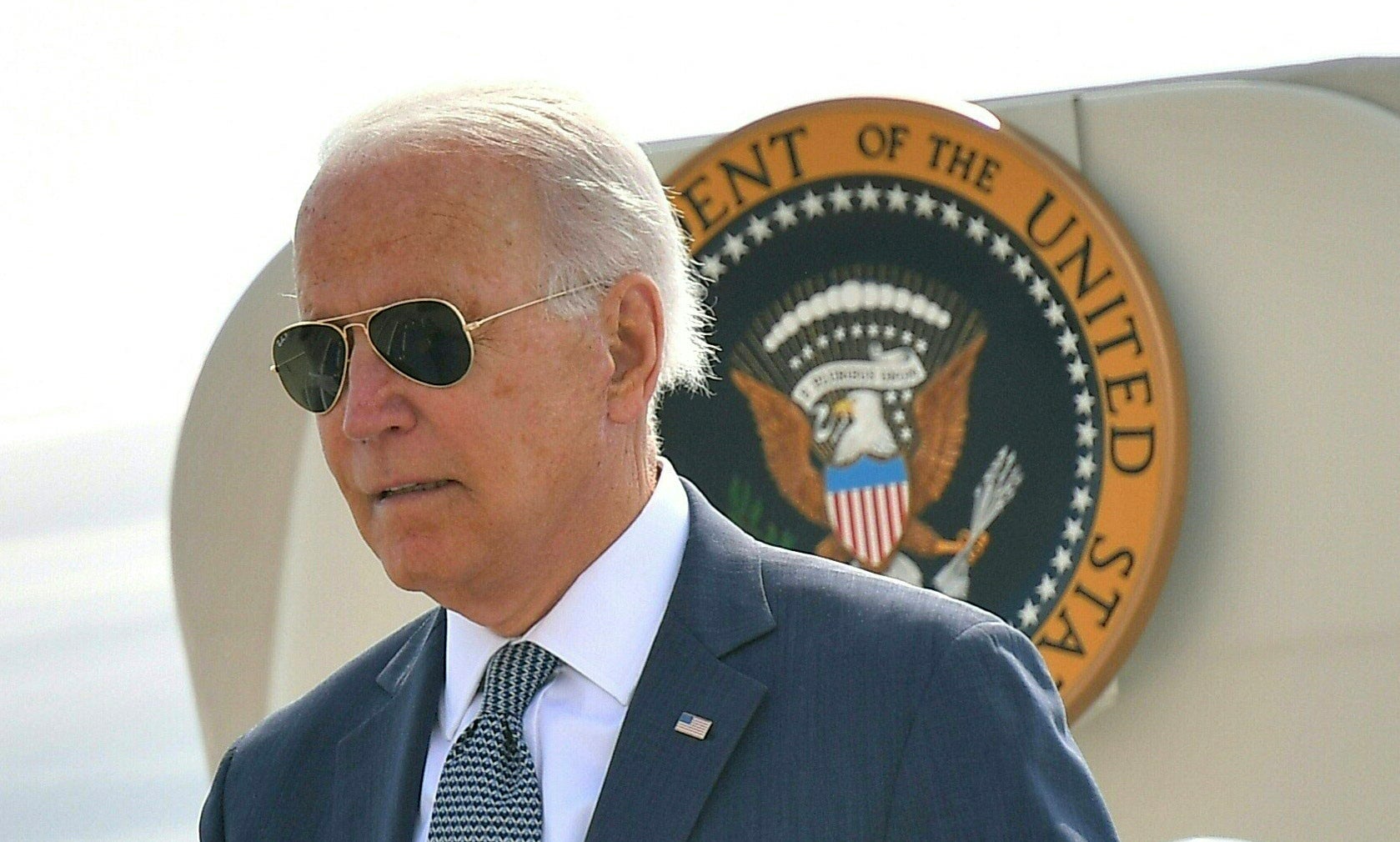

The pictures suggested that her meeting with the Queen was a lot more relaxed than the Johnson lunch; the two women – practised, it might be said, in the less obtrusive school of politics – appeared cordial and at ease in each other’s company. But it is testimony to Merkel’s unrivalled international standing, as she prepares to bow out as German chancellor after 16 years, that her latest trip is to Washington, where she will be the first European leader invited to the Biden White House. Johnson might have been the first to meet the US president one-on-one, re-asserting the “special relationship” on the eve of the G7. But it is Merkel who takes the honours in Washington.

And, like Biden’s recent European tour, the encounter will send a very particular message. Biden may have little to gain politically from the meeting – after all, a new German chancellor, perhaps even a differently constituted coalition, will hold power in Berlin by Christmas – but his talks with Merkel will reinforce the point he drove home repeatedly during his European tour, that he is absolutely not Donald Trump.

And we can expect pictures expressly designed to contrast with one of the most eloquent images of the Trump years. You remember the one, from the 2018 Canada G7, that captures Merkel, at the front of an assembly of international leaders, apparently remonstrating with Trump, who is seated opposite, arms defiantly folded. There will be none of that this time: genuine engagement and respectful formality are likely to be the orders of the day.

If the contrast between Trump and Biden will be striking, Merkel will be nothing more nor less than herself. Now in her fourth term, she has grown into something akin to the acknowledged leader of Europe. No recent national, or EU, leader has come as close as she has to representing the continent of Europe with authority on the world stage. But she did not seek that role; it was rather, by dint of her long leadership, personal discretion, and acknowledged competence at the helm of the EU’s biggest economy, thrust upon her.

As a protestant and a woman – a divorced woman, at that – she was something of a curiosity in the CDU. But she was a valuable curiosity, whose career to that point signified everything the united Germany aspired to be

It is hard now to reconcile the oh so familiar figure of Merkel, with her blonde bob and her uniform of sensible shoes and black trousers paired with an infinite range of coloured jackets, with the almost girlish political neophyte who began her methodical climb up Germany’s government and party ladder in her thirties, before, quite ruthlessly, turning on her patron, the venerable, but flawed father of German reunification, Helmut Kohl.

Between 1990, when she entered the Bundestag (parliament) of the just-united Germany as MP for a constituency in the former East, and 2000, when she became leader of the centre-right Christian Democratic Party (CDU), Merkel served first in Kohl’s government – successively as minister for women and girls and environment minister – then, after Kohl’s 1998 election defeat, as party general secretary and party chairman (leader). In 2002, she took over as leader of the parliamentary opposition alliance of the CDU and its sister-party, the CSU, and it was from here that she became the centre-right’s candidate for chancellor in the 2005 general election.

With hindsight, her progression to the top of German politics looks methodical, but the timeline is deceptive. Merkel’s advancement was facilitated less by her own actions than by missteps on the part of those who would otherwise have blocked her way.

But she also had crucial assets. One was her patron: she was spotted early on by the then chancellor, Helmut Kohl, who made her a minister within a year of her entering the Bundestag and called her his “Maedchen” (girl) – though the relationship seems to have entailed nothing untoward. But also, as Kohl perhaps recognised, she had not only political gifts, but a profile that was perfect for a chancellor of the reunited Germany at a time when the first flush of excitement was wearing off.

Merkel was an “Ossi” – as the west Germans sometimes disparagingly called their fellow-citizens from the east – and had spent her early life in a small town, Templin, north of the then divided Berlin, where her father was a Lutheran pastor. The family had relatives in the west, with whom she occasionally spent holidays and who supplied what were then luxuries, such as jeans, but otherwise she took a conventional path, avoiding politics and graduating in physics at the University of Leipzig, before settling into a research post at the then GDR Academy of Sciences in Berlin.

It was only as the East German regime was tottering that she made the first tentative steps into politics, becoming active in the Democratic Alliance that then joined with West Germany’s CDU. In 1990 she stood as MP for Mecklenberg-Vorpommern, a seat she has held ever since, at a time when politics in the east was uniquely open and the CDU was riding high after unification.

As a protestant and a woman – a divorced woman, at that, having parted from her husband, Ulrich Merkel, five years after an early marriage – she was something of a curiosity in the CDU. But she was a valuable curiosity, whose career to that point signified everything the united Germany aspired to be.

Already in those early days, some detected a steely ambition beneath her diffident and self-effacing exterior. Whether that drive was there at the start, or developed later, what is true is that she proved more than equal to each advancement that came her way, and could not have progressed as she did in a very male-dominated party and political establishment without a record of competence.

Two episodes in particular illustrate the ambition beneath. One was her move – bold, pitiless, and indeed historic – to break with Kohl, recognising that the sleaze burden, from his involvement in illegal party funding schemes, now outweighed his value to the party as the chancellor who had secured unification after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

What Kohl subsequently saw as his protegee’s great betrayal took the form of an article in the German weekly, Die Zeit, a year after the CDU-CSU’s 1998 election defeat by the Social Democrats. Although no longer chancellor or party leader, Kohl was still an MP and the party’s undisputed elder statesman. Her killer-sentences were these: “The party must learn to walk now and dare to engage in future battles with its political opponents without its old warhorse, as Kohl has often enjoyed calling himself... We who now have responsibility for the party, and not so much Helmut Kohl, will decide how to approach the new era.”

In so saying, Merkel was not only calling on the party to abandon Kohl, but making a brazen bid for the party leadership (which became hers a year later). It also showed the acute sense of timing that has distinguished her career. She later went some way towards mending fences with the great man, naming him an informal adviser soon after she became chancellor. By then, though, she had taken the party into its “new era” and could afford this small show of magnanimity.

Another glimpse of her ambition – more discreet, but still telling – came the previous year, when she had just become CDU general secretary and so eyed as a future leader. Senior party representatives were deputed, it is reported, to talk to her privately about the dissonance, as they saw it, between her living arrangements and the Christian precepts of the party. The point was that she had long been cohabiting with Joachim Sauer, a chemistry professor at Berlin’s Humboldt University, but was not married to him – it was said, by choice. The “grey eminences” reportedly laid it on the line: regularise your relationship or forget further promotion. The couple married, quietly, in December that year.

For all the evidence of her political acumen and quiet drive, however, some aspects of politics did not come easily to Merkel. Even after more than 10 years in the upper reaches of national politics, she was still a poor campaigner. I followed her in the weeks before the 2005 election, when she was the CDU-CSU nominee for chancellor, and her speeches at rallies could be woeful, and made to appear more so by the deft political touch of her chief opponent, the Social Democrat chancellor, Gerhard Schroeder. Lapses in her TV debating and lacklustre performances on the stump led to Merkel squandering a double-digit poll lead in the last weeks of the campaign, so that the two emerged on election night neck and neck.

Then, though, Merkel demonstrated once again that combination of staying power and focus that has served her so well. She showed up for the traditional election-night party-leaders’ round-table – an agonising reflection on live TV about what went right or wrong – and had to listen as Schroeder boasted interminably of having won. Merkel allowed him to talk, and talk, before quietly stating, correctly, that her CDU-CSU was ahead.

Three weeks and many rounds of negotiations later, she was finally able to announce the formation of a “grand coalition” between the CDU-CSU and the Social Democrats that she would head, becoming Germany’s first woman chancellor. Schroeder left politics altogether.

At the time, there was much speculation that the coalition was too fragile to last. In the event, not only did it survive for the full term (unlike Schroeder’s Red-Green coalition that preceded it), but Merkel was re-elected four years later with an increased number of MPs.

Looking back, prematurely perhaps, it is hard to predict exactly what, from her 16 years in power, will survive her?

It can reasonably be argued that Merkel benefited, both during the campaign and as chancellor, from the unpopular, but necessary, labour reforms brought in by her predecessor. Once in office, though, Merkel proved herself an astute politician in her own right, successfully navigating the perils of her finely balanced coalition with the same qualities that had brought her the job: patience, discretion and, the ability – albeit often after much deliberation – to make and stick to decisions.

It is true, that as she continued in power, those same qualities were questioned and seen as having a downside. Critics coined the verb “merkeln”, meaning to prevaricate, or dither, while achieving nothing. At the same time, for a politician who rarely evinced any emotion, she earned, first a grudging, then much wider, respect. Despite not having children – beyond two grown-up step-children from Sauer – she became familiarly known as “Mutti” – Mummy of the nation.

As the elections went by, she also became a vastly more confident and convincing campaigner, improving immeasurably at each. At what Merkel already intimated would be her last general election four years ago, she was almost unrecognisable from the awkward and self-conscious figure who had addressed her first national rallies a decade and more before. By then, though, the high point of Merkel’s electoral power, was probably past.

This was the election of 2013, her third, where she came close to winning an overall majority, but was unable to capitalise on that strength, because her first-choice coalition partner, the free-market FDP, failed to reach the threshold to enter parliament, forcing her into another “grand coalition”. Three of her four governments have thus been more centrist than she might have preferred, even though her second, with the FDP, was arguably her least successful.

Looking back, prematurely perhaps, it is hard to predict exactly what, from her 16 years in power, will survive her? Or even what were the highs and the lows, because the failures and achievements are often bound up together.

One is undoubtedly the euro crisis, which was a product of the 2007-8 global financial crash. Still in her first term, Merkel lacked the sureness and authority in the European Union that she later gained. The task may have been impossible, but she could not balance her personal and north European instinct for thrift against what many Germans saw as the fecklessness of the southern Europeans, especially Greece. The quarrel that followed laid bare many of the EU’s underlying divisions and was only partly resolved by Mario Draghi’s famous pledge, as President of the European Central Bank, to do “whatever it takes” (to save the euro).

It could also be argued, though, that even if most Germans stuck to their cautious financial instincts, Merkel learned from that experience and never again allowed doubt to be cast on Germany’s commitment to the EU. Years later, Merkel supported the hard line the EU took in the Brexit negotiations, having rebuffed David Cameron’s pleas for concessions before the UK’s referendum. Keeping the EU central to German policy is partly how, inside and outside Europe, Merkel has come increasingly to be seen as Europe’s leader.

Another high-low point of Merkel’s chancellorship is the refugee crisis of 2015. On the one hand, Merkel’s decision to admit more than 1 million refugees was admirable and testimony to the modern, inclusive and tolerant state that post-war Germany had largely become. On the other hand, the popular welcome soon wore off and Merkel’s decision is already storing up potential difficulties, even for a country as efficient at receiving newcomers as Germany. Acts of terrorism, as well as a spate of sexual assaults in Cologne and elsewhere the following New Year, have been gifts for the far right, and made Merkel’s bid for a fourth term in 2017 more difficult than it would otherwise have been.

That election was close, and the formation of a government – yet another “grand coalition” – stretched for a record six months. Early in her second term, Merkel had declared multiculturalism an “utter failure”, insisting that newcomers should be integrated into the German mainstream. The generation of 2015 could be the ultimate test of this.

Germany’s record on the environment and climate change is the third aspect of Merkel’s mixed legacy. Her second cabinet post in the 1990s was environment minister, and she has kept a keen eye on green issues ever since. As Chancellor, and with Germany’s Greens becoming a serious political force, she pledged to phase out coal-burning power stations and reverse the Schroeder government’s anti-nuclear stance. All that came to a precipitate end, however, when she took the decision, almost overnight, to close all Germany’s nuclear power stations in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan. The decision relied on a switch to renewables and reduced energy use, which has not been smooth.

Her decision to speed an end to nuclear power in Germany, however, had a knock-on effect on another high-low aspect of Merkel’s record: relations with Russia. The German government became even more attached to plans for a new gas pipeline from Russia, Nord Stream 2, which met fierce opposition from elsewhere in Europe and from the US, as it increased Europe’s reliance on Russian energy and deprived Ukraine of pipeline transit fees.

That pipeline is now practically complete, but the project serves to highlight the inconsistencies in Germany’s Russia policy under Merkel, which has favoured pragmatism, while at the same time trying to uphold the security and human rights agendas which for some other EU countries come first. Germany’s strength is such, however, that it can usually get away with lurches to one side or the other, the medical treatment provided for the Russian opposition figure, Alexei Navalny, last summer after his poisoning, being a case in point.

The contradictions extend to Merkel’s relations with Vladimir Putin, which have seemed, at best, frosty – for all the evident similarities between them: both grew up under communism, both experienced its demise and switched sides around the same time, both speak each other’s language, and they have been in power for almost the same time. Perhaps, though, they know too much about each other to have anything more than a wary relationship. Putin, for instance, is reported to have tried to unnerve Merkel by bringing his dog to one meeting, knowing of her aversion to the animals.

Merkel also failed in her joint attempt with the French president to invite Putin to an early summit with the EU, following the US-Russia rapprochement at the Geneva summit. The rebuff from the EU majority was seen as evidence of Merkel’s declining influence as her term nears its end.

In another respect, however, her declining authority at home received a late boost – and her legacy as chancellor too – from the completely unforeseen intervention of the Covid pandemic. While governments and health services in other countries thrashed around for remedies, Merkel, a scientist, recouped all her standing as a calm and authoritative leader. The only time she seemed at loss was when forced to reverse a last-minute Easter shutdown. Her broadcast apology was a rare admission of error from a chancellor, who suddenly looked uncertain – and much older – than before.

It was a rare glimpse of the inner world of a woman who has kept her distance and revealed very little of her private self over her two decades in the public eye. Politically, it may be deduced that she is further to the right on security and economics than her three “grand coalitions” with the Social Democrats have allowed her to be. She entered politics as post-Cold War Atlanticist, and is famed for an observation she made at Davos in 2013, about Europe having only 7 per cent of the global population, producing only 25 per cent of the world’s GDP, but accounting for almost 50 per cent of global social expenditure and would have to find new ways of maintaining its living standards.

Given that she is within weeks of leaving politics, Merkel’s talks in Washington are likely to be more reflective than policy-making. But the meeting is a strong signal from the US president that Germany has now replaced the UK as Washington’s bridge to Europe

Personally, she has kept a modest lifestyle, preferring her own flat to the Chancellor’s official Berlin residence and shopping in her local supermarket, where her basket was observed early in the pandemic as containing cherries, soap, toilet rolls, a bottle of ordinary wine. She cooks Pflaumenkuchen (a German plum cake) and spends her holidays walking or cross-country skiing or relaxing on the Italian island of Ischia. She likes opera, and was a regular – with her husband, an even more reserved figure than Denis Thatcher used to be–- at the annual Wagner festival at Beyreuth.

That is pretty much all Merkel has divulged. But it should also be said that, in all her years in politics, there has been not the slightest whiff of corruption or nepotism or anything else untoward: no favours advanced, no contracts fixed, no friends or relatives on boards, no plagiarised dissertations. And she has only twice appeared at all vulnerable: on crutches after a skiing accident in 2014 and, more recently, suffering from a visible tremor (which seems to have passed). So exceptional were these intimations of mortality that they sparked trepidation around the world.

It is almost three years since Merkel announced that she was resigning from the CDU leadership, would not stand in the coming elections and would leave politics after the new government is formed. And despite failing to pass the baton to a chosen successor – Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, now defence minister, proved unsuited to the task – she has retained widespread respect, if not affection, in German political circles and beyond. Her farewell appearances, at the CDU party conference, at the EU, and in the Bundestag, have been low-key, business-like affairs, but met with prolonged applause.

At her last appearance in the Bundestag, where she answered questions for more than an hour, she was asked for her reflections on Germany’s next big challenge and what recommendations she would make to her successor. Noting that when she became Chancellor there was no such thing as an i-Phone, she singled out digitisation and access, concluding: “The more information you have, the more efficient you can be.” She then turned and put her papers into her briefcase, before acknowledging the applause.

Given that she is within weeks of leaving politics, Merkel’s talks in Washington are likely to be more reflective than policy-making. Both are veterans and beneficiaries in their different ways of the end of the Cold War. US-European differences – on China policy and trade, as well as Washington’s perennial complaints about German underspending on defence – can be left for Merkel’s successor, probably the new CDU leader, Armin Laschet, who is expected to favour continuity over change.

There could, though, be two more specific results from the meeting: one tangible – a move to coordinate international efforts on recovery from the pandemic – and one less so; a strong signal from the US president that Germany has now replaced the UK as Washington’s bridge to Europe. That could be a fitting accolade for a German chancellor whose biography so personifies recent German history and whose well-judged and well-timed departure should stand as a model for democracies everywhere.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments