The Godfather at 50: The man who made the mafia an offer they couldn’t refuse

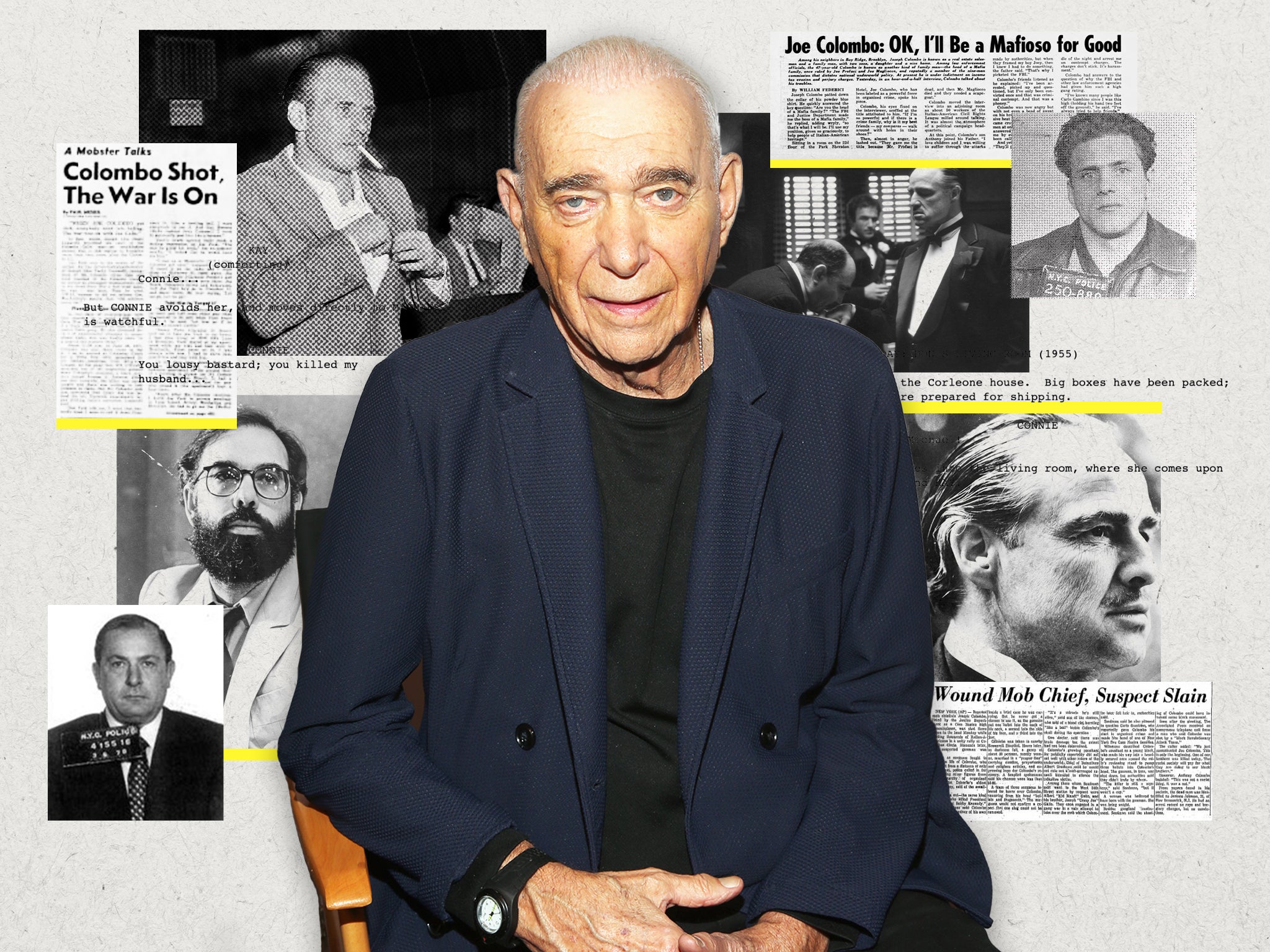

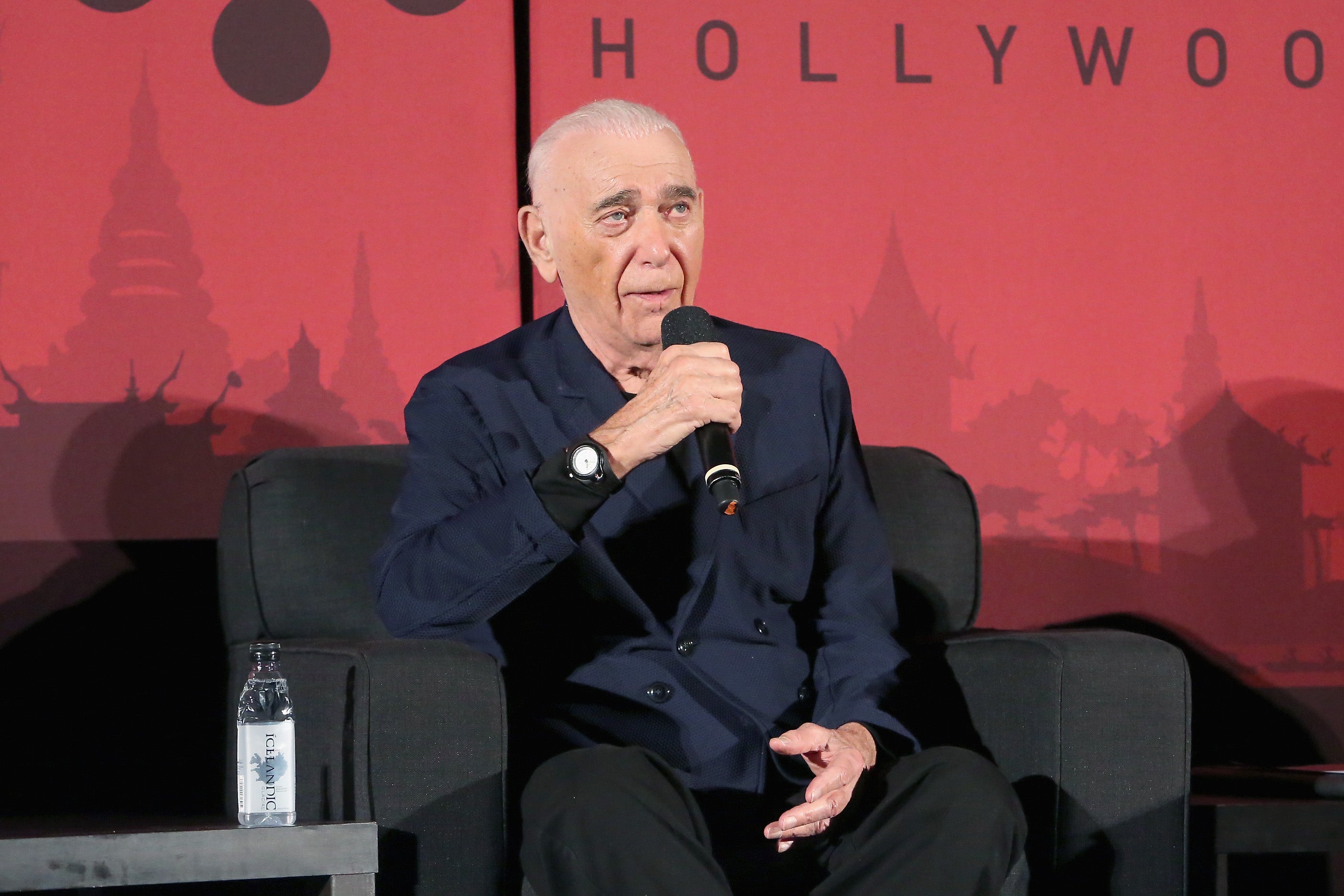

The Godfather is often regarded as the greatest movie of all time. But much less is known about its producer, Al Ruddy, and his dealings with the real mafia. Sean Smith tells his story

When The Godfather went on general release exactly half a century ago today, its anxious producer, Al Ruddy, snuck into a crowded New York movie theatre eager to gauge the audience’s reaction to the closing moments. As the music swelled and the credits rolled, Ruddy was hardly able to breathe. And then the most astonishing thing happened: nothing. “The lights came on and it was the eeriest feeling of all time: there was not one sound, no applause. The audience sat there, stunned,” recalled Ruddy years later.

When The Godfather opened nationwide in the closing week of March 1972, the same phenomenon of hushed, reverence was observed in movie theatres across the US. Instantly hailed as a masterpiece, The Godfather became the highest grossing movie of all time and would go on to sweep the board at the Academy Awards the following year.

As the film’s producer, Ruddy picked up the Oscar statuette for best film and proffered the usual thanks to cast and crew but he was, however, unable to acknowledge the nefarious assistance the movie received from the underworld. It was years later when he finally admitted that, “without the mafia’s help, it would’ve been impossible to make the picture”.

Paramount had picked up the rights to Mario Puzo’s novel, The Godfather, when it was still at draft stage. But even after it had unexpectedly become a publishing sensation and global bestseller in 1969, studio executives had no intention of turning it into a major movie. Besieged by television’s irrepressible rise, the struggling film studio had become so risk averse that instead its initial plan was to cash in on the book’s popularity by churning out a low-budget movie adaptation just to turn a quick profit.

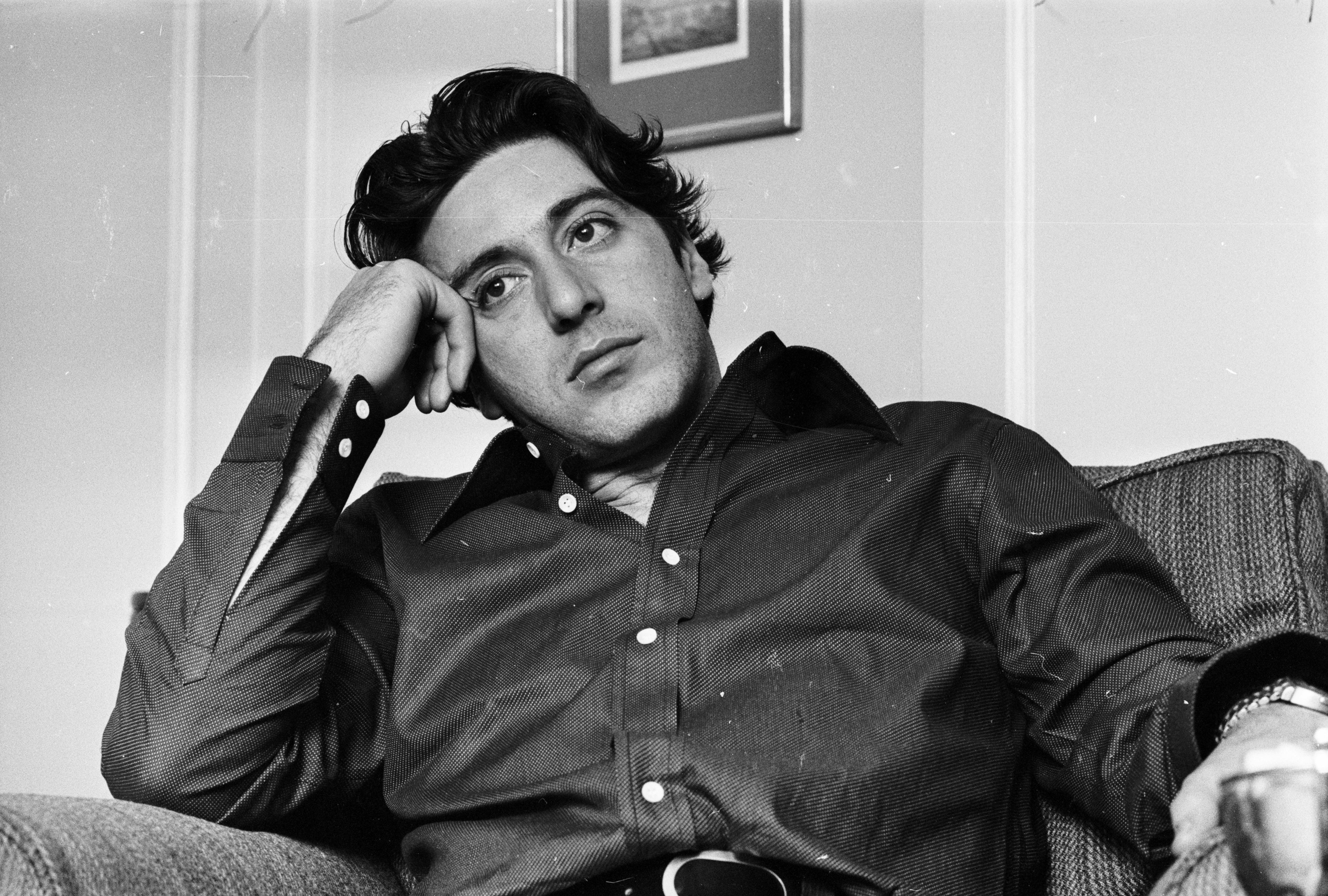

That’s why Paramount made the inexperienced Ruddy an offer he couldn’t refuse; they invited him to produce The Godfather because in his nascent producing career he had already demonstrated Hollywood’s rarest skill: bringing in modest movies on time and within budget. Initially tasked with the challenge of staying within Paramount’s $2.5m budget, Ruddy was asked to update the novel’s events into a cheaper modern-day setting by replicating New York street scenes on flimsy studio sets.

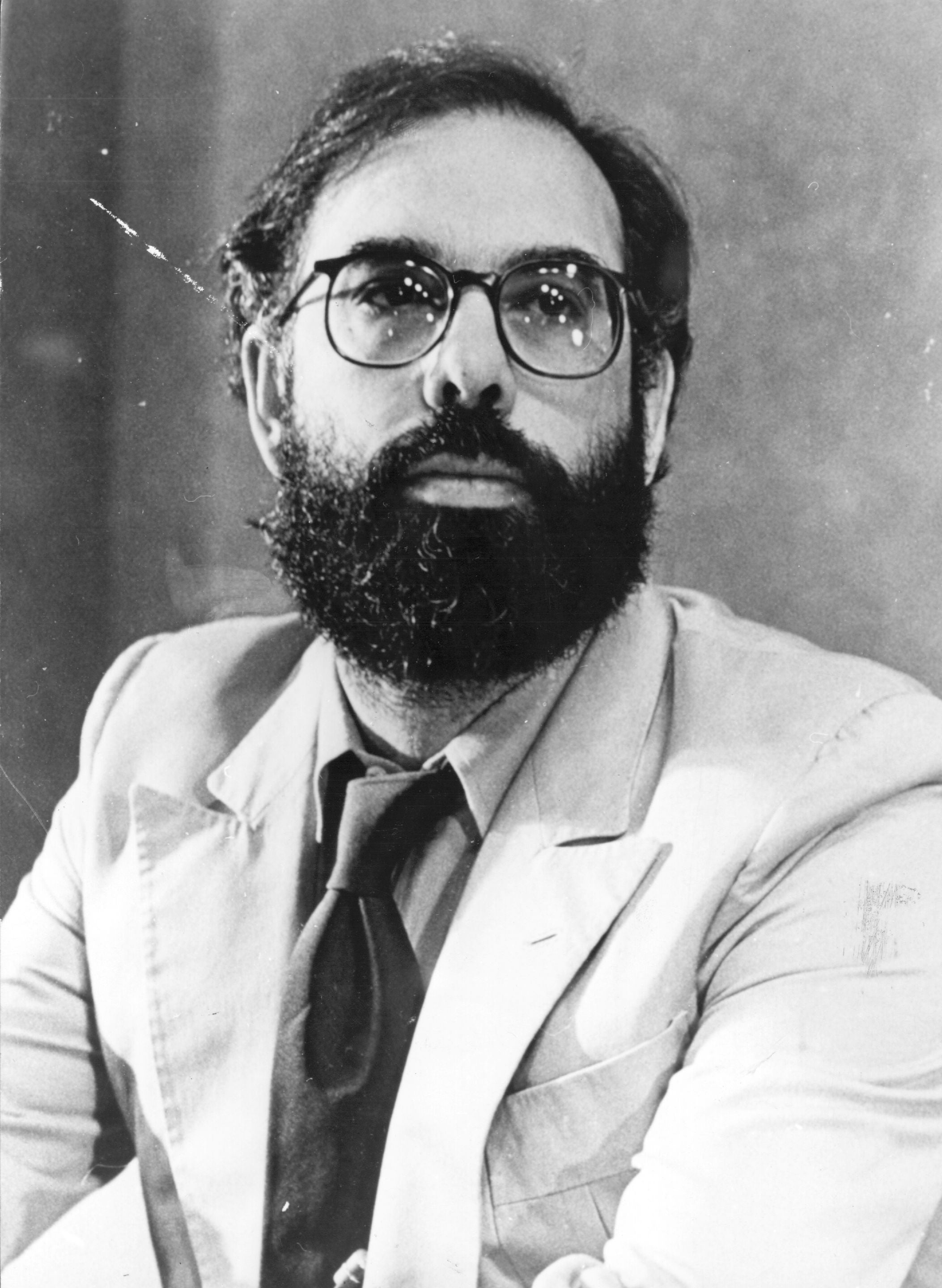

Also, Paramount opted for Francis Ford Coppola to direct The Godfather because – like Ruddy – he was available, inexperienced and cheap. But that decision would prove to be a false economy. From their initial meetings with Paramount’s brass, Ruddy was impressed by Coppola’s audacity in facing down the bean-counting executives who tried to curtail his vision.

Coppola insisted on rewriting the screenplay with Puzo, turning the film back into a 1940s period drama even though that decision alone would effectively double the movie’s budget to $6m. Ruddy backed his director on every significant call. The director quickly recognised that Ruddy was not just another “suit”. Ruddy’s sense of humour, emotional intelligence and pragmatic skills as a fixer were wedded to an inherent likability that enabled him to get things done: as a film producer, he was a natural.

Coppola also insisted that – in the interests of authenticity – key scenes would be shot on location in Little Italy, the mafia’s natural habitat in lower Manhattan. It was this decision that would prove to have such severe implications for Ruddy’s health and safety because it would bring him within range of the shadowy orbit of underworld figures who were desperate to stop the film from being made.

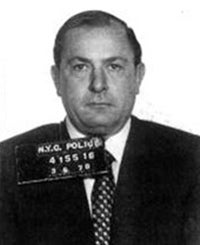

Although he was facing federal racketeering charges, Colombo openly implied that any film studio unwise enough to expose the secrets of Cosa Nostra would pay the ultimate price

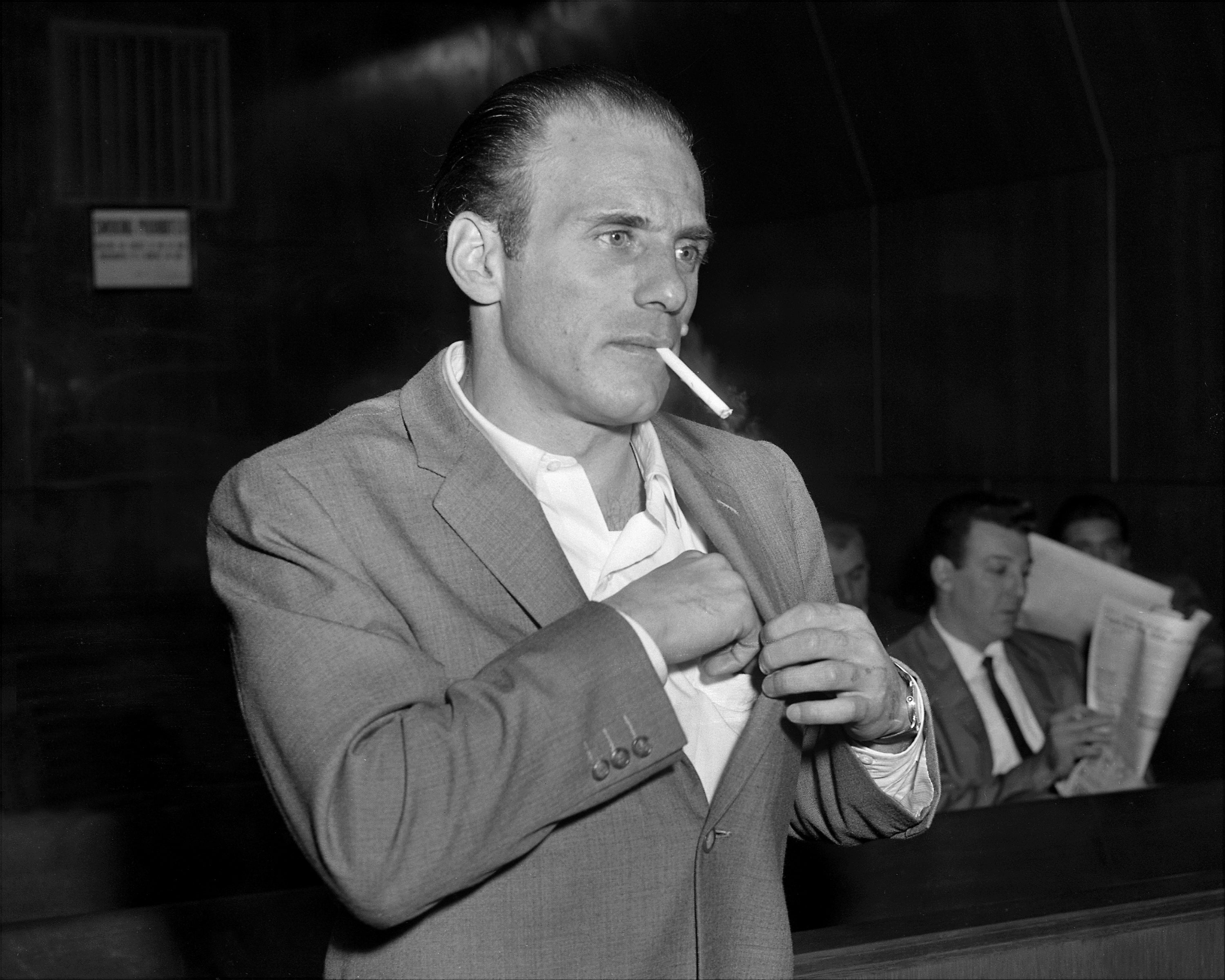

Ruddy had to contend with the newly founded Italian American Civil Rights League, which was determined to block the movie and its perpetuation of the gangster stereotype. However, rather ironically, almost from its very inception, the league's leadership had been infiltrated by a notorious mafia leader, Joe Colombo. He had swelled the league’s membership to 100,000 and the coffers of its campaigning war chest to $1m.

In a formidable show of force an estimated crowd of a quarter of a million attended the league's inaugural New York rally on 11 June 1970. Although he was facing federal racketeering charges, Colombo openly implied that any film studio unwise enough to expose the secrets of Cosa Nostra would pay the ultimate price: “Those who go against the league will feel its sting,” he warned.

When Paramount’s senior vice-president, Bob Evans, received a menacing phone call, he tried to redirect the caller to the film’s producer, Ruddy, only to be told in a strong Italian accent: “When we kill a snake, we chop off its head first.”

But Ruddy would receive many death threats too. Once, when he sensed he was being followed around Los Angeles, he swapped cars with his secretary in an attempt to evade the tail. The next morning she discovered Ruddy’s car with the windows shot out with a warning note stuck to the dashboard. There were even bomb scares at the office buildings of Gulf and Western – Paramount’s parent corporation. And at ground level, the mob’s foot soldiers were particularly active in lower Manhattan too.

Having secured access deals with local residents and business owners in Little Italy, The Godfather’s location scouts would return later to find that those permissions had been mysteriously revoked. Unions had been infiltrated by the mob to such an extent that when Colombo threatened to use strike action to shut down production at Paramount Studios, Ruddy had no choice but to meet with him in person.

In a private meeting with Colombo and two of his burly associates, Ruddy produced The Godfather’s imposing 155-page script, inviting them to read it and take out any material they found offensive. But Colombo was so intimidated by the script’s technical jargon that he didn’t make it past the first page tossing it to his lieutenants who were equally unwilling to engage with it.

Yet, crucially, on a personal level, Colombo and his associates liked Ruddy and decided that they trusted him enough to make the movie – with the one proviso that the word “mafia” be expunged from the script. Given that the script contained just one mention of the word, Ruddy was more than happy to comply.

But rather predictably the deal came with other strings attached. Colombo wanted the proceeds from the film’s premiere to be donated to the league as a “goodwill gesture”. He would also subsequently make sure that most of the location fees paid to the residents of Little Italy would instead be funnelled to the mob.

Al Ruddy agreed to meet with Colombo a few days later to confirm details of the deal only to be duped into attending a Colombo-led press conference. Ruddy's deal with the mafia triggered a national media furore that led to precipitous falls in Gulf and Western’s share price. Carpeted by Gulf and Western’s incandescent chairman, Charley Bluhdorn, Ruddy was fired on the spot and his deal with the mafia disavowed.

While the film’s production was suspended pending the appointment of a new producer, Coppola lobbied Paramount hard for Ruddy’s return, pointing out that without his contacts the film would have to be abandoned. Ruddy was quietly reinstated; Coppola’s motives weren’t entirely selfless. Without his producer’s loyal support he knew he would lose key battles over casting and – in all probability – the director’s chair too.

Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, Diane Keaton and Robert Duvall have become so synonymous with their roles that it’s easy to forget that they were seen as such idiosyncratic choices that studio executives seriously considered replacing Coppola with a more compliant director.

Initially, Paramount hated the idea of casting Brando as the Godfather because he was regarded as box-office poison and not worth the disruption that followed him on to film sets. But with Ruddy’s help, Coppola persuaded Brando to screen test for the role of Vito Corleone; the actor padded out his cheeks with tissues and assumed the gravelly voice that would inspire so many bad impressions at family christenings for decades to come.

Paramount’s executives were so mesmerised by the performance that they didn’t recognise Brando on first viewing and were so reluctantly impressed that they acquiesced to their director’s choice of Godfather.

At least Brando was a star – albeit, one with diminished lustre; but Coppola’s decision to cast the then unknown Al Pacino in the lead role of Michael Corleone appalled Paramount. Studio chief Bob Evans disparaged the diminutive Pacino as “the runt” and argued for an established star to carry the movie at the box office: Robert Redford, Ryan O’Neal, David Carradine, Jack Nicholson, and Warren Beatty were all screen tested.

Without Ruddy’s advocacy, it’s likely that Coppola and Pacino would have been fired and replaced within the first few weeks of filming in March 1971. Coppola was so convinced that he was going to be ousted in a putsch that he tried to block the casting of his sister as Connie Corleone because he didn’t want her to witness his humiliation.

And when executives viewed the first daily rushes in their private screening room they thought seriously about pulling the trigger. The film’s dark, claustrophobic cinematography confirmed their worst suspicions that Coppola was blowing money they could ill afford on a glorified arthouse movie. They had been unnerved by Coppola’s claim that he was going to use the mafia family saga as an allegory to chronicle the evils of corporate America.

But Ruddy’s astute decision to bring forward the filming of the famous scene when Pacino’s Michael slays an underworld rival and corrupt police chief, changed everything.

The Godfather’s restaurant scene is regarded as one of the greatest scenes in cinema history and is taught in film schools as a masterclass in film editing. Crucially – at the time – it afforded Coppola and Pacino a stay of execution.

For the first time Paramount’s executives could sense that Coppola and Ruddy were presiding over something that was going to be truly special. In the course of the movie's production, the mob had also fallen under the spell of Ruddy’s production team, even operating as unofficial advisers. While filming the famous scene when Brando is gunned down in the streets of Little Italy, local mafiosi corrected the way the assassins held their guns, while the notorious mafia boss Carlo Gambino was sat in a cafe around the corner, sipping black coffee.

The FBI photographer who is berated and attacked for intruding on the Corleone wedding celebrations at the beginning of the movie is played by an actual photographer who had connections to the mob. And many of the extras at the Corleone wedding were supplied by Colombo’s contacts. And when Coppola was trying to cast the Godfather’s most loyal hitman, Luca Brasi, he opted for Lenny Montana the imposing 6ft 6in former enforcer for the Colombo family, who had made a living literally breaking legs before his belated foray into showbiz .

If the mafia had become fascinated by Hollywood, the feeling was mutual. Brando absorbed the mannerisms of the mobsters who appeared around the set, carefully appropriating them into his Oscar-winning performance. James Caan, who played the hot-headed Sonny Corleone, spent so much time socialising with mobsters that the FBI opened a file on him before realising he was an actor on the brink of stardom.

Not everyone was delighted by this ever closer union. Colombo’s co-operation with Ruddy had enraged one of his most volatile underworld rivals – the notorious Joey Gallo. When Colombo was gunned down at the Italian American Civil Rights League rally in 28 June 1971, it was widely believed to have been a reprisal for having his head turned by Hollywood and breaking the silence code of omerta.

Across town, at almost exactly the same time, Coppola was filming the movie’s dramatic climax where Michael Corleone consolidates his position by co-ordinating the assassination of the heads of the five families.

Colombo would spend the rest of his life in a coma, finally succumbing to his injuries in 1978.

The revenge killing of Joey Gallo in Little Italy within the first fortnight of The Godfather’s release provided publicity of the most macabre kind and helped propel it past Gone With the Wind as the highest grossing movie of all time. Today, The Godfather and it's equally astonishing sequel regularly vie with Citizen Kane in polls of the greatest film of all time,

In a case of life imitating art, FBI surveillance teams noticed that after the film’s release, wise guys even began to greet each other with the overly elaborate greeting rituals popularised by the film.

Ruddy’s tribulations are about to become immortalised in The Offer a Paramount mini-series where the beleaguered producer is played by Miles Teller. This time around, Paramount is playing Ruddy’s story for laughs, even though he has famously claimed that, “everyday making The Godfather was the worst day of my life.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments