What awaits the next chancellor in the post-Merkel inbox?

Germany’s next chancellor faces a huge to-do list, dominated by crumbling infrastructure, strikes, and the formation of a European army. Whoever takes over, Merkel will be a hard act to follow, reports Mary Dejevsky from Berlin

The world cannot say it had no warning. Angela Merkel has timed her departure as Chancellor of Germany after 16 years and four terms in office as methodically as she has exercised power for most of that time. She stated after her last election victory that she would be serving her last term, and no one interpreted that as a bluff. She relinquished the leadership of her party, the Christian Democratic Union, three years ago to clear the way for a successor to become established in good time, or at least that was the plan.

But with only days to go before Germany votes on Sunday in the parliamentary elections that will produce her successor, there still seems to be a widespread lack of comprehension that someone else will be occupying her desk at the Chancellery, someone else will be speaking from her lectern in the Bundestag, and someone else will be representing Germany on the European and global stage. There may be a hiatus – the time it will take for the victor of what looks set to be a close-run contest to form a new coalition government – but Merkel herself will not be in power any more.

While the reality of her departure may not have fully set in, the image of Merkel as the ideal leader for Germany and Europe certainly has. Her last weeks have been suffused with a rosy glow of global approval, with envious eyes cast from abroad, including from the UK, where John Kampfner’s book, Why the Germans Do it Better, played perfectly into the international, and especially the British, mood.

So I have to say that, in the light of all this, it was something of a shock to arrive in pre-election Germany last week – after a gap of a year – to find that the mood among voters themselves, and the concerns reflected in the German media, hardly matched the Angela-nostalgia so prevalent almost everywhere else.

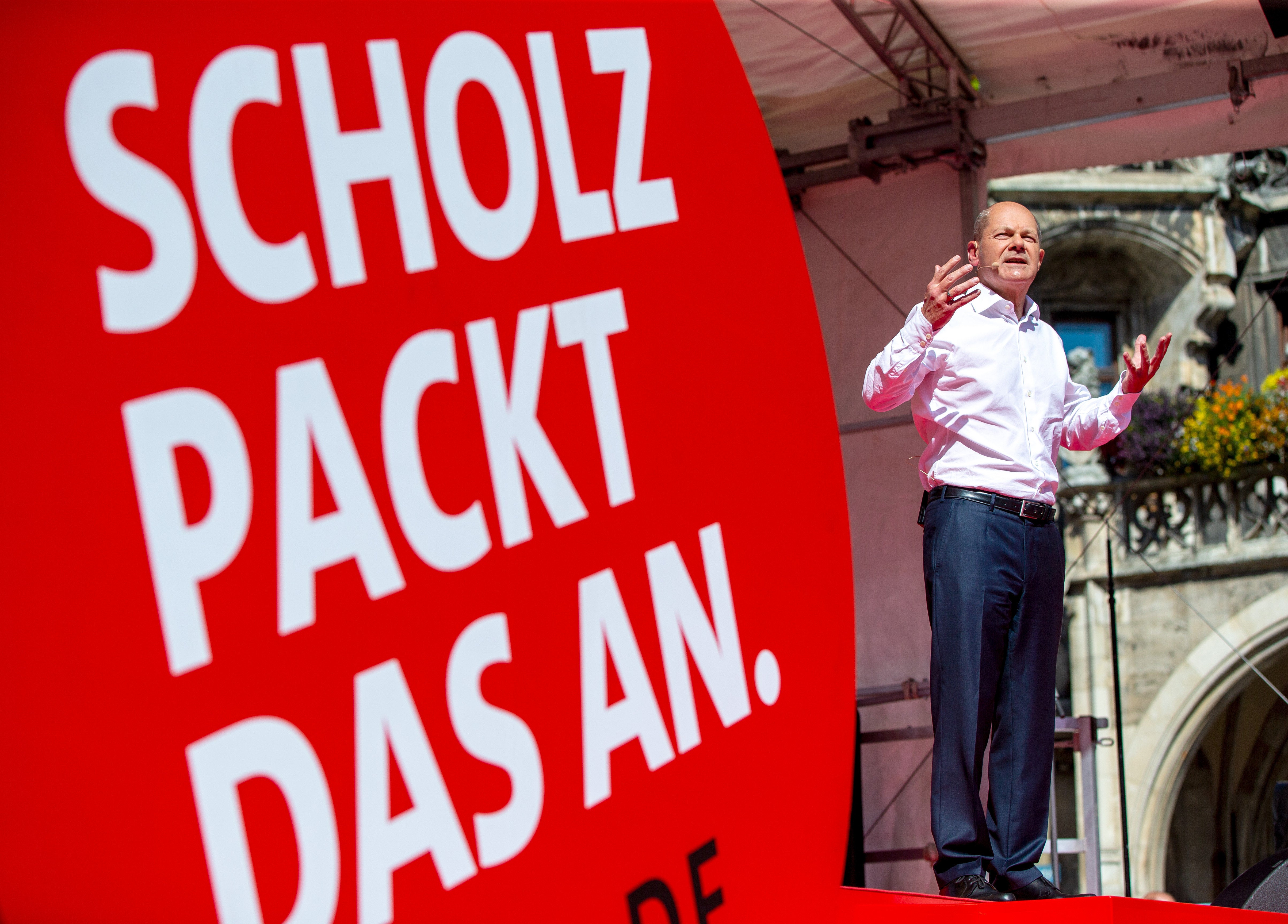

The effect is disconcerting because, on the one hand, all the accoutrements of a German federal election are in place – the colour-coded posters, the snappy slogans, the television debates and the market-square rallies taking place in all corners of the country – and the main candidates are all campaigning on their ability to emulate Merkel. The Social-Democrat, Olaf Scholz, even put out a campaign poster boasting his unique suitability to be “Kanzlerin” – using the feminine form of the word for Chancellor as neat shorthand for Merkel, in a rare example of a male politician citing a female role model.

On the other hand, there seems to be more discontent with more aspects of life in Germany than I can remember in decades of visiting the country and reporting on its elections. A recent survey conducted by the European Council on Foreign Relations, a Brussels-based think-tank, went some way towards confirming this. It found that while around a third of EU citizens thought that Germany’s glory days were coming to an end, more than half (52 per cent) of Germans saw Germany already as a declining power.

That sentiment might be explained as signalling a regretful parting with Merkel, with the belief – reinforced perhaps by the calibre of the candidates currently on offer – that any other leader was likely to be inferior. But it also suggested a feeling that the rot had already set in and that Germans will never have it so good again.

The specific areas of concern, that can be seen and heard all over the Germany capital and further afield, not only build up into a sizeable inbox for Merkel’s successor, but cast doubt on her legacy as chancellor for Germany, even if her contribution as an international figure and a leader for Europe remain largely unscathed.

So what, in German eyes, has gone so wrong? An oft-cited symbol of German difficulties in the late-Merkel period is the new Berlin-Brandenburg airport, which finally opened last October, almost 10 years late, more than 4 billion euros over budget, and straight into the winter wave of a global pandemic. It seems efficient enough, but architecturally uninteresting, and lacking any dedicated high-speed connection to the city centre. Cynical Britons might expect that of London; we tend to think – as Kampfner wrote – that Germans do it better.

The biggest complaints can be lumped under the working title “infrastructure”. Germans do not have a history of being, how shall I put it, early adopters. They were among the last western Europeans to take to credit and debit cards in a big way. Their high-speed broadband is not as universal or as high-speed as you might expect of a country reputed to be a technological powerhouse, with coverage less than in France or Italy.

This meant that during the various pandemic lockdowns, Germans by and large were no better equipped than Britons to cope with remote-everything. Digitalisation in public services has not gone nearly as far as in the UK – which you might think is a good thing, given its potential to divide the tech-savvy from the rest – but is not what might be expected of the homeland of Siemens and Porsche.

Angela Merkel was an early champion of the need to combat global warming, before it became a cause that no political leader could afford to disregard

Planning election campaign-related trips, I have been surprised by the time it takes to reach other parts of Germany from Berlin. Granted, Germany is a big country and a federal country, and regional centres are spread more evenly than in the UK, where all roads and railways tend to lead to London. And some aspects of the transport system are enviable in their efficiency: the way the various types – especially regular trains and local S-bahn trains fit together, making transfers simpler than they would be in many countries. But the high-speed rail network is nothing like as developed as it is in France or Spain or Italy, and journeys that you might think could be accomplished there and back in a day, simply can’t be.

Neglect of infrastructure has also been cited as a contributory factor in the catastrophic flood damage experienced in the Eiffel region of western Germany this summer. I happen to know the worst-affected area, the Ahr valley, relatively well, being rather partial to the dry red wine that is grown there. There is a balance to be struck between flood prevention works and preserving glorious landscape, and disasters can happen. Sometimes there just isn’t anyone to blame. But the regularity with which floods seem to strike parts of Germany – often, or so it seems, in election seasons – and the devastation they cause suggests that building or reinforcing flood defences might be given more priority than it has.

It could be argued that Merkel was a political beneficiary of election-time flood damage. Edmund Stoiber, her predecessor as centre-right candidate for chancellor and then front-runner, was defeated in the 2002 election after seriously mishandling a flood emergency in Bavaria, opening the way for her to be nominated three years later. That might have spurred her into action as chancellor, but there seems to have been little progress since.

Two observations might also be in order. First, that big infrastructure projects cut across Germany’s very clear distinction between federal and regional (land) responsibilities. So credit and blame for inaction or inaction can all too easily be passed between the two.

The other is that Merkel and her successive governments have a defence, in the massive amount of work and money that has been required to bring former East Germany up to something like the standards of the former West. What might be called “levelling up” is still a work in progress – even in the centre of Berlin – and may be a reflection as much of the scale of the task as of government failings. Then again, it has been more than 30 years...

Then there is climate change. As a scientist (a chemist) by training and a one-time environment minister, in the mid-1990s, Angela Merkel was an early champion of the need to combat global warming, before it became a cause that no political leader could afford to disregard. Partly as a result of the summer flooding, it is now top of concerns expressed by many German voters – and so high on the agenda of all major candidates, not just the Greens. Which has led to the spotlight falling on what Merkel did as opposed to what she said; her record, in the view of many, leaves some catching up for her successor to do.

One decision, highly acclaimed at the time, but possible to see with hindsight as a panicked response, was her decision to speed up the phasing out of nuclear power promised by her predecessor, in the immediate aftermath of the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan. Part of the result is that Germany is now more reliant on fossil-fuels than it would otherwise have been, and on natural gas imported from Russia, hence Merkel’s staunch support for the just-completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline. The nuclear decision was an unusual example of Merkel making a decision with huge ramifications almost instantaneously. She has stuck to it, but it is something that her successor may need to revisit, as it has not only limited Germany’s room for manoeuvre in its relations with Russia, but arguably raised energy prices to consumers.

The pandemic has also cast its shadow over this year’s campaign in ways that might not have been predicted even a few months ago. In the first wave of the pandemic, Merkel was riding high. A rare scientist at the top of a national government, she seemed surefooted in leading Germany’s response and the country’s well-respected health system - a social insurance system - held up well. The mortality rate was much lower than that in the UK and among the lowest in Europe.

Just one issue that could have been awkward has so far largely remained largely out of the campaign: the progress or otherwise and the cost of integrating the million-plus refugees

Now, though, there is criticism on many sides and on many aspects. From the left have come accusations that the insurance system favours the better-off over poorer Germans, and that a UK-style health service, free at the point of need, would be fairer and serve the country better. The relative slowness of the vaccine roll-out has been another complaint – although Germany, like France and Italy has caught up with the UK. There have also been murmurings about the dilatory response to the pandemic from the European Union, which are largely unjust, given that health is a national responsibility, as it is a devolved responsibility in the UK.

Other areas of voter discontent include what is seen as the clunky German banking system, which for all its old-fashioned rigour has been unable to get to grips with large-scale money-laundering; schools and universities that are not equipping their students for the new world of digital and artificial intelligence; and even the political system itself, which is seen as sclerotic and unresponsive to new problems that emerge in the faster-moving circumstances of today.

The price of housing, especially in Berlin where rent controls were recently relaxed, is another issue on voters’ agenda, as are business ethics after Volkswagen was found to have cheated on its emissions standards. As if this were not enough, Germany’s much-praised system of industrial relations is fraying, with the public services trade union, Ver.di, not just threatening but taking strike action in the quest for a 6 per cent pay rise.

Just one issue that could have been awkward has so far largely remained largely out of the campaign: the progress or otherwise and the cost of integrating the million-plus refugees who benefited from Merkel’s generosity in 2015. No candidate, other than the leader of the right-wing Alternative fuer Deutschland, has broken the politically correct consensus, although derogatory comments swirl around the social media.

Merkel has also done her successor a favour in one respect: rather than re-opening the door she threw open six years ago with the confident assurance that “wir schaffen das” (we’ll manage it), she has undertaken that Germany will fulfil its requirements under EU provisions, but not offered to do more. The legacy of 2015 could nonetheless return to haunt her successor and progress in integration is something that the new chancellor will need to watch.

There are several conclusions that might be drawn from this long, but still not exhaustive, list. One would be the extent to which Germans are currently preoccupied with their own welfare and the functioning of their own state and institutions. Merkel may have cut an impressive figure on the international stage, and amplified Germany’s voice in the European Union, but Germans appear to feel that there are many aspects of their domestic lives that warrant more urgent attention.

Another might be how closely their concerns mirror those currently exercising politicians and the public here in the UK and elsewhere in Europe. The pandemic, it seems, has highlighted defects that are common to many advanced economies, and Germany – for all its reputation as superior in so many areas – is not exempt. The question might even arise as to whether Merkel’s Germany has perhaps been resting on its laurels?

While the next chancellor will have all these disparate causes of dissatisfaction crowding his (or less likely her) in-box, one of the most urgent dilemmas he may have to confront lies in foreign policy and Europe. The hurried US withdrawal from Afghanistan affected Germany, too. This was partly because it had troops and aid contingents in the country, and Afghan service staff who needed to be evacuated; Germany was one of the last countries to complete its exit, just before the British. It was partly, too, because the withdrawal left a bitter taste among veterans and the families of those who had been injured or died, who felt – like some of their counterparts in the UK – that their mission had been in vain.

Chiefly, though, it was because the US withdrawal, given the go-ahead by President Biden with minimal, if any, consultation with the allies, left Germany in the lurch, and this was felt particularly keenly because of the continued sensitivity of military deployments for a country that is reluctant, for obvious historical reasons, to use even the limited troop capability it has.

The way Germany felt it had been treated by the US seemed all too reminiscent of the Donald Trump presidency, when Merkel had emerged as the de facto leader of the anti-Trump EU, with one crucial difference. Then, the European allies had been primed to expect the unexpected, whereas Joe Biden had been welcomed as a predictable and alliance-minded president. The chaotic end of the Nato-led presence in Afghanistan called into question the commitment of the US to its European allies and placed the question of a self-standing European military capability on the EU’s agenda.

It might seem paradoxical that all three leading candidates to succeed her are trying to present themselves essentially as another Merkel

New life was breathed into calls along these lines made previously by the French president, Emmanuel Macron, while the (German) president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, used her state of the union address to the European Parliament to give the – as yet barely embryonic – project an extra push.

The EU, she said, had to be able to provide greater stability in its own backyard and elsewhere, and be capable of mounting its own missions, without Nato or the UN. The EU had been held back, she said, not just by “a shortfall of capacity” but “a lack of political will”. “You can have the most advanced forces in the world, but if you are never prepared to use them, what use are they?”

Her words constituted a landmark of a kind, as Germany has in the past been about as averse to the concept of a European army as the UK. It is now clear, though, that whether to support the formation of a “European army” will loom large in the in-tray of Germany’s next chancellor, and could threaten rifts with either German public opinion or Brussels, or both. Merkel never had to make that decision. Her successor may have to, and before he or she has amassed either the experience or the clout that Merkel latterly enjoyed in the EU.

Without Merkel, Germany’s influence in the EU is likely to be diminished, initially at least. And there are already signs that Macron is positioning himself to fill the space her departure will surely leave. The European Union will thus find itself dealing with such delicate questions as distributing the post-pandemic recovery fund, likely legal challenges to the operation of the gas pipeline Nord Stream 2, and the flouting of EU standards by Poland and Hungary, without Merkel’s moderating influence. The current equilibrium, imperfect as it is, could be a lot harder to maintain.

Germany’s next chancellor faces a huge to-do list, dominated, but not limited to, domestic issues that may come to be seen as having been neglected by Merkel. Or, it might be judged, more charitably, that she took the only reasonable course, given the need, first, to complete the integration of the former East and then to deal with the emergency of the pandemic.

Of the three main candidates to succeed her – who have taken part in the first three-sided election debates known as a ‘Triell’ (as opposed to a Duell) – one is the current leader of her CDU party, Armin Laschet, who heads the generally well-regarded administration of North-Rhine-Westphalia, Germany’s richest state by GDP. He began as the favourite, but his political skills leave something to be desired.

One is Merkel’s current deputy and finance minister in her “Grand Coalition”, the Social Democrat, Olaf Scholz, who appears to have escaped the curse that so often blights the careers of any junior partner in a coalition and is currently the front-runner. The third is the Green candidate, Annalena Baerbock, who started out strongly as the favoured outsider, but whose inexperience has betrayed her, along with what has emerged as a common liability among German politicians – alleged plagiarism in her academic thesis.

Given the level of popular unhappiness with the unfinished business Merkel is bequeathing, it might seem paradoxical that all three leading candidates to succeed her are trying to present themselves essentially as another Merkel, rather than offering the voters an alternative. That, though, is a measure of the dominance Merkel came to exert over her 16 years in office and the gap she will leave in German and European politics. The next chancellor, whoever it is, will find it hard to escape her shadow.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments