Heroes and villains of 2020: How the human spirit didn’t just rise, it soared

Brexit and coronavirus will go on shaping our lives for years, but with a deal done and a vaccine in the works, we might start talking about them a little less, and the heroes of 2020 a little more, writes Tom Peck

There will be no fireworks at the stroke of midnight this New Year’s Eve but wander out on to the doorstep, cup an ear against the night and you might just hear an echo of a familiar sound. Was that a whoop? A cheer? Was that the distant whack of wooden spoon against saucepan?

There have been terrible mistakes and epic failures with abysmal consequences. But they weigh scarcely a feather in the balance against a great accumulated mass of quiet, stubborn indefatigability.

“If you can fill the unforgiving minute with 60 seconds worth of distance run,” wrote Rudyard Kipling. And if you can’t run, well, you can walk a hundred laps around your garden and raise £33m for charity. That will more than do.

Captain Tom Moore – who appears to be spending Christmas 2020 on a British Airways freebie in Barbados and absolutely who can blame him – is hardly the only one of us who declined to be defeated by it all. It certainly didn’t go unnoticed, back in March, when a period of national and indeed international house arrest suddenly began, that for a long while those who really mattered had been underpriced and undervalued.

It has never been clearer to see that the world does not go around without the supermarket shelf stacker, the takeaway delivery driver, the post woman and yes, the Amazon delivery man. We have all been quick to heap praise upon ordinary men and women, doing the low paid work we cannot live without, and quite right too.

But there’s nothing heroic about picking and packing in an Amazon fulfilment centre, manning the tills or delivering the Chinese takeaway. People working in shops, facing down an awful disease that they would sooner not catch have even been described as “brave”.

This is the lexicon politicians tend to reach for to ascribe greatness to ordinary people they let down. During the D-Day commemorations last year, a veteran called Eric Chardin breezily explained in an interview with the BBC that there was nothing especially “brave” about what they did that day. They were there, doing what they did, because they had no choice, and most of them were pretty angry about it.

It’s not merely that the “brave” delivery driver is being let down by a different system, but that in the moment that his indispensability has been so blindingly illuminated, his lot in life is getting harder. To take but one example, the pandemic has made America’s billionaires almost £800bn richer. Amazon’s CEO Jeff Bezos’ personal net worth has more than doubled, to around £187bn.

Meanwhile the job of making people’s lives easier becomes ever harder, the pay lower, the work ever more insecure, the app-driven gig economy badged as a kind of creative destruction but accounts for little more than the stripping away of a hundred years of rights and protections for workers none of which were won without a bitter fight.

People, generally, are horrified by this, but if it’s not to change now, then when will it? And given it can’t change without price rises, do people even want it to?

While the Black Lives Matter movement took on the symbols of slavery, and as a consequence, the national conversation was diverted onto the easy ground of statues and historiography, and away from the far more difficult issues of deep rooted structural prejudice and inequality based on race. Edward Colston’s crimes happened a long, long time ago. That modern slavery is alive and well, its fingerprints to be found on the tiny components inside the phone on which you are probably reading this, is a reality we are still unprepared to face.

For a short while, during the summer, not long after the latest rule change of impossible complexity, there was talk of Covid having killed “compassion”. That we had become a nation of snitches, ready to shop the neighbours for having one too many people in their garden, or itching for the public shaming of anyone to have strayed onto the wrong side of whatever the restrictions might be.

Perhaps that’s so, but mainly, social distancing, lockdown and everything else we have endured has been willingly undergone by millions of people for whom Covid-19 poses precious little risk, to protect those who are more vulnerable. It has been a great national act of charity, and some people, some businesses, have stoically paid unimaginably high prices indeed.

There was, of course, one national hate figure in all this, but he is deserving of no sympathy, even now. Dominic Cummings was not the only national figure found to have broken the rules. The others, Scotland’s chief medical officer Dr Catherine Calderwood and the scientific advisor Dr Neil Ferguson, promptly resigned.

It was Mr Cummings’s decision to instead hold a press conference and fatally undermine his own government’s public health messaging by stubbornly refusing to tell the truth. It beggars belief, even now, that the government’s former chief strategist, a little private schoolboy and entirely self-appointed man of the people, could have held the people in such contempt.

That he really did think “the people” were stupid enough to believe that he had considered the prime minister’s time “too valuable” to tell him about his secret family trip to Durham, which would come to take over the life of the nation for more than a week, speaks volumes about the man, arguably more so than the claim that he took his wife and child out for an hour-long spin in the car to test his eyesight.

The prime minister’s litany of failures are far too long to even list. It will always be hard not to view Boris Johnson through the polarising prism of Brexit, but even his greatest admirers for the most part came to see he was uniquely ill-suited for the occasion. Most prime ministers, for example, don’t need to spend a week at Chequers, sorting out a divorce, an engagement, and an announcement of a new baby. And thus most prime ministers don’t advise their staff not to bother them in what would turn out to be an absolutely crucial phase of an unprecedented public health crisis.

The over-promising and under-delivering have reached such a level that nothing the man says can ever be believed. The moonshot, the “world beating” test and trace, the “sending coronavirus packing” in 12 weeks, the normality by Christmas, all these false dawns came up so dark that they no longer offer a glimmer of hope. The most recent promise, normality by Easter, was disbelieved the second it was made. It is a straightforward failure of leadership, compounded by an almost pathological lack of integrity. This stuff matters.

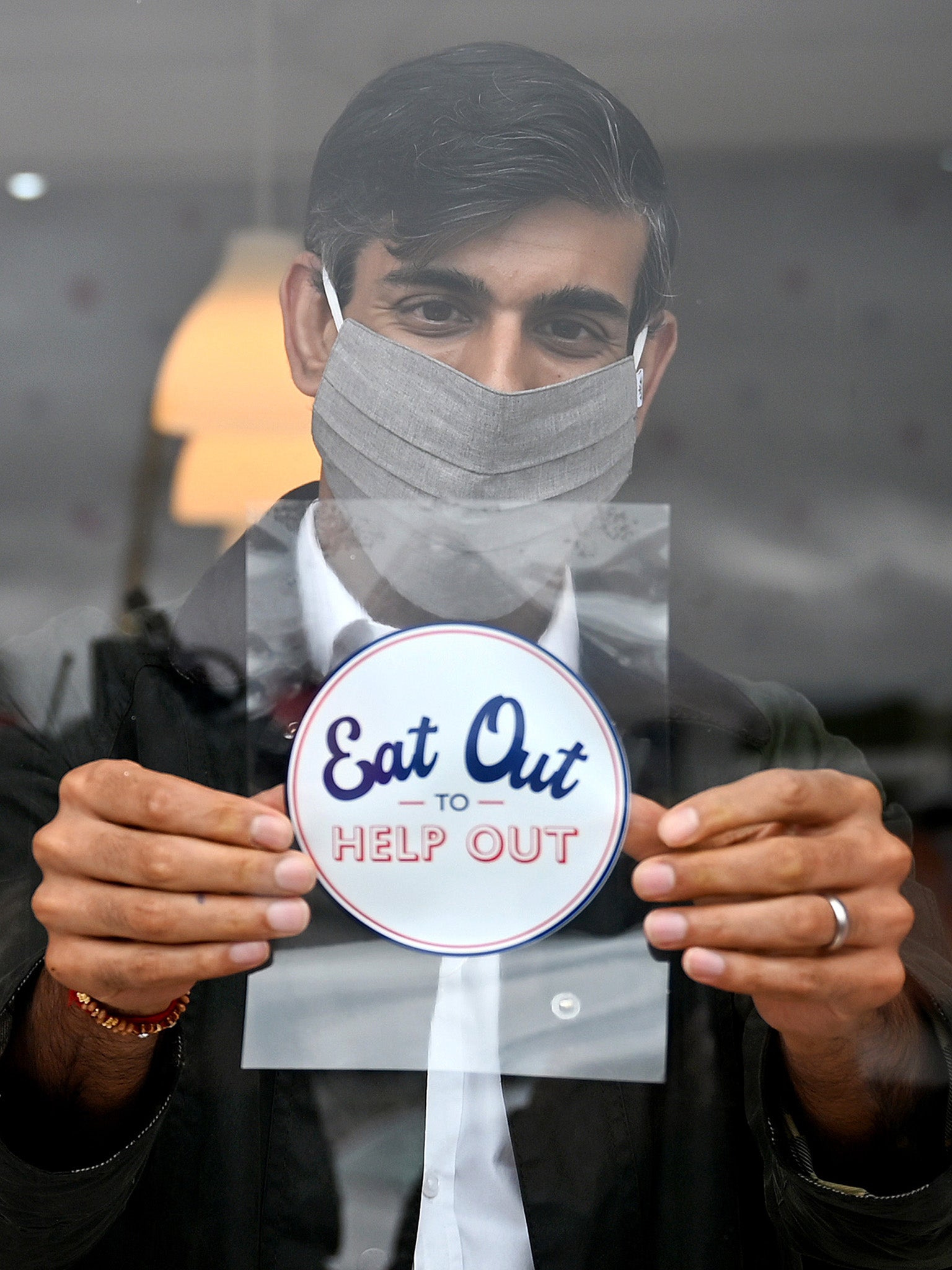

In the early days of the pandemic, public morale was almost entirely saved by the bright new thing, Rishi Sunak, who seemingly had limitless billions for everyone. Health secretary Matt Hancock became his polar opposite. As Sunak flashed the cash, Hancock set wildly ambitious testing targets that were only quite kept through some audacious fiddling of the figures.

But those roles have been reversed a little more recently, and they deserve to be reversed more fully. It was Sunak who was setting out plans to “live with the virus”, and Hancock who realised this absolutely couldn’t be done, that only mass vaccination was the answer.

The test and trace system is much maligned, but the tracing aspect has been a challenge for almost every government everywhere in the world, and our testing regime has been imperfect but a success.

That the first Covid vaccination in the world took place here became very quickly lost in the Brexit culture war. It shouldn’t have done. It was a real achievement.

Of course, coronavirus has exposed shocking shortcomings, fuelled by a decade of austerity that might have been easier to ignore. Whatever was written down the side of a bus, Brexit will not make those problems easier to solve, because it will, as a matter of economic fact, make the country poorer, and, therefore, the capacity to improve far smaller. It is an awful outcome.

The Brexit deal is, finally, done. It’s the first trade deal in history to ever make trade between its two signatories harder, not easier, but that is where we are. It will at least relegate Brexit to a less permanent presence in our lives. In some ways, and fully aware of the glibness, the country needed something else to do, something else to talk about.

Brexit and coronavirus will go on shaping our lives for years, but it may not be long before we all start talking about them a little less. In the meantime, we have been forced to search out our capacity for decency, and it has been shown to be vastly larger than we might have imagined.

That should be cause enough for a bit of optimism, whatever that used to feel like.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments