1971: The year that changed the fabric of Britain for ever

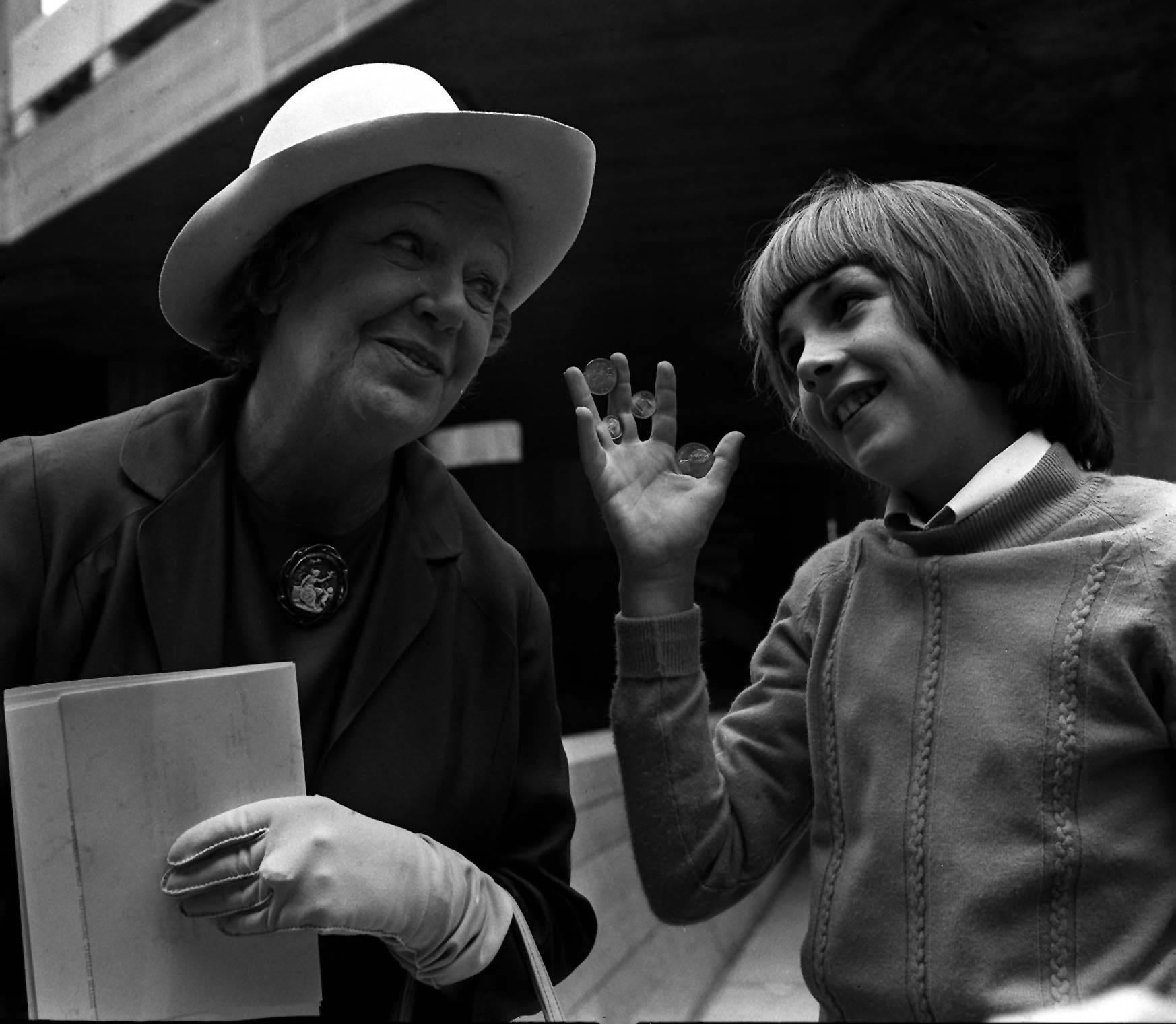

On Valentine’s Day 50 years ago, Britain kissed goodbye to hundreds of years of history when it changed over to decimal coinage – but that wasn’t all that changed, writes David Lister

Fifty years ago on Valentine’s Day 1971 there was a seismic change in Britain, affecting every man, woman and child in the country. But it was only one of many changes that contributed to making that year a pivotal one in the social and cultural history of the nation.

It was a year in which music changed from pop to rock. The key demographic of record buyers switched from male to female. TV and film became ever more groundbreaking, the conflict between the establishment and the youth generation more marked. But none of those aspects of 1971 can be said with utter confidence to have affected every single member of the population as the first great change of that strange year. On 14 February, Britain kissed goodbye to hundreds of years of history, and changed over to decimal coinage.

A memorable TV news clip of the time showed an elderly lady being interviewed. She pleaded: “If they insist on introducing it, OK. But couldn’t they have waited till us old ones died off?”

Yes, it was goodbye to pounds shillings (20 of them made a pound) and pence (it took 240 of those to make a pound), and for quite some time afterwards the decimal pence were known as new pence, so loathe was the country to simply forget an old friend. It was goodbye to some beloved names, the ten bob note, the half-crown, the florin, the threepenny bit, the halfpenny (pronounced haypenny), the farthing, that one-quarter of an old penny which, amazingly, could actually buy something down the sweetshop.

Indeed, one or two of those had been “disappeared” by the Royal Mint in the few years before the changeover (the farthing made its last purchase in 1960). At first the new and old coinage ran alongside each other. Posters and leaflets tried to soothe the confused. ITV even broadcast the subtly but also unsubtly titled Granny Gets the Point in which an elderly woman is coached in the new coinage by her grandson.

And let us not forget the sixpence, 6d in old money and old language (2.5p in decimal coinage). That remained in circulation until 1980. Who knew what an emotional tug that had on the nation? A former Treasury secretary, Dick Taverne, recalled: “There was a passionate public campaign 'save our sixpence'.

"People were very fond of the coin. They said it was part of our heritage. It was thought a terrible thing to get rid of the sixpence. I remember in the course of the debate, one of the Labour members screaming, 'But what about the housewife, she is going to miss the sixpence, she is going to be exploited - how dreadful the decision to abolish the sixpence'. It was a very emotive issue."

Even though some prices stealthily went up with the changeover, a look back at the prices of the day still shocks with its apparent cheapness. A three-course steak meal at a Berni Inn, a night out long forgotten, cost 80p. And, of course, you could smoke while you ate, would probably drive there in a car without seat belts and then go home to the grand choice of three television channels, not one of them offering 24-hour news. If it was a Saturday night, there was at least a cop drama – Dixon of Dock Green with his avuncular persona and comforting catchphrase, “Evenin’ all”.

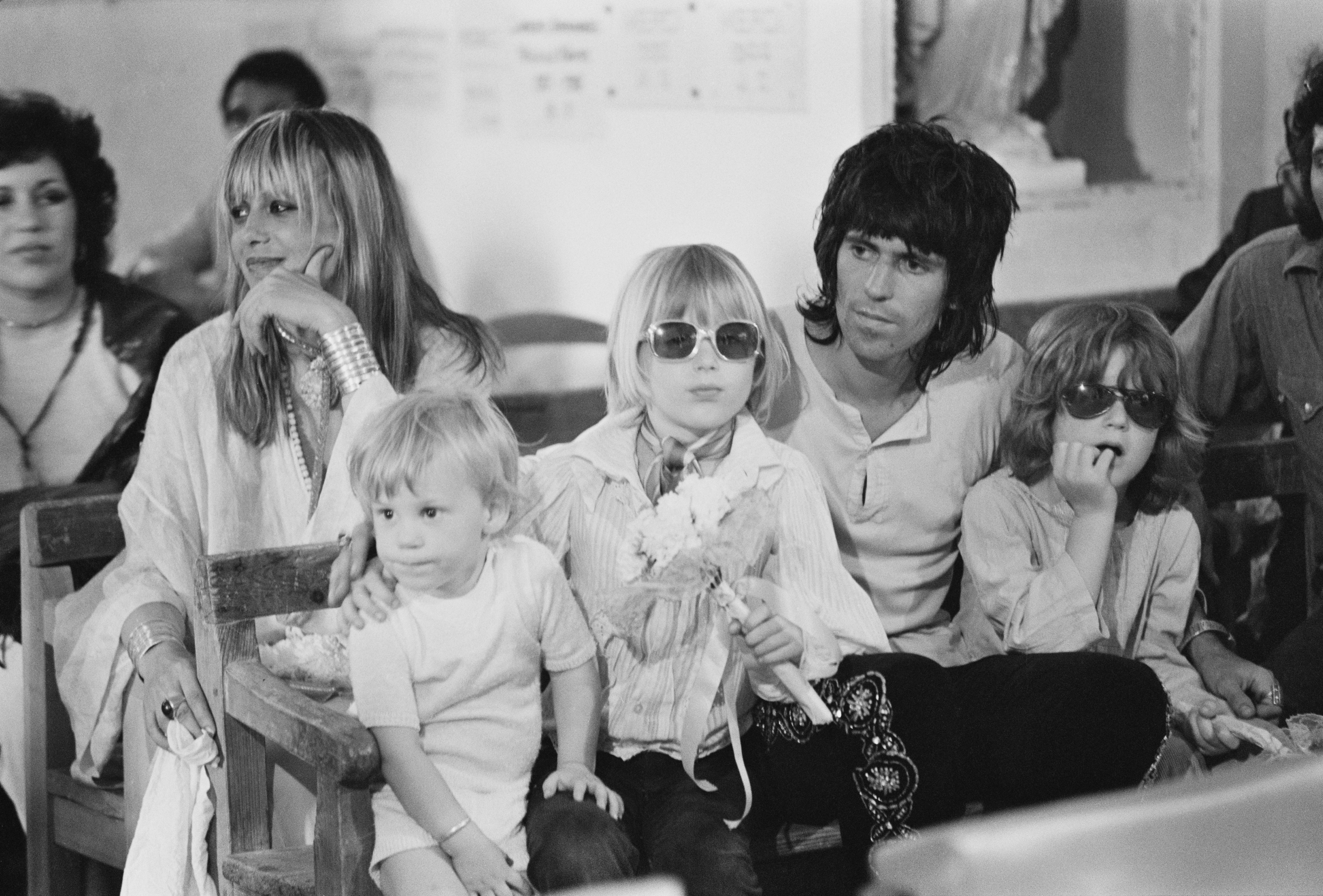

It was all enough to make some want to leave the country. The Rolling Stones certainly did, though less for love of the sixpence and more to avoid the high taxes of the time. They went to the south of France, lived and recorded there, and in the process brought about the change from pop to rock.

David Hepworth in his excellent book 1971: Never a Dull Moment, a history of music in that year, points in particular to a celebrated picture of a half-naked Keith Richards lounging on the floor of his French mansion with his guitar, surrounded by nubile women and fellow musicians, effortlessly portraying a lifestyle half the world’s young wanted to emulate.

Hepworth says: “These images of unshaven young men so confident in their appearance that they can afford to be slovenly about it, their clothing apparently made up of whatever garment had been at the end of the bed when the noonday sun tickled them into wakefulness … holding precious Martin guitars by their necks, long cigarettes dangling from their mouths as they reach for their first coffee or cognac of the day and make their way down to the villa’s dank cellar … in the background like so many extras were their lissom, blonde girlfriends and their tousle-haired children. It was a dream of a new form of living, a fantasy in which you could live the life of a hippy on the budget of a banker."

At concerts, Sixties-style screaming was a thing of the past. Audiences listened studiously, which did not always appeal to the artists. I was at a Led Zeppelin concert at Kent University in which Robert Plant yelled and swore at the audience to “stand up you lazy f***ers” and applaud the drum solo. Alternatively, they might have been too stoned. Anyway, Plant was roundly booed.

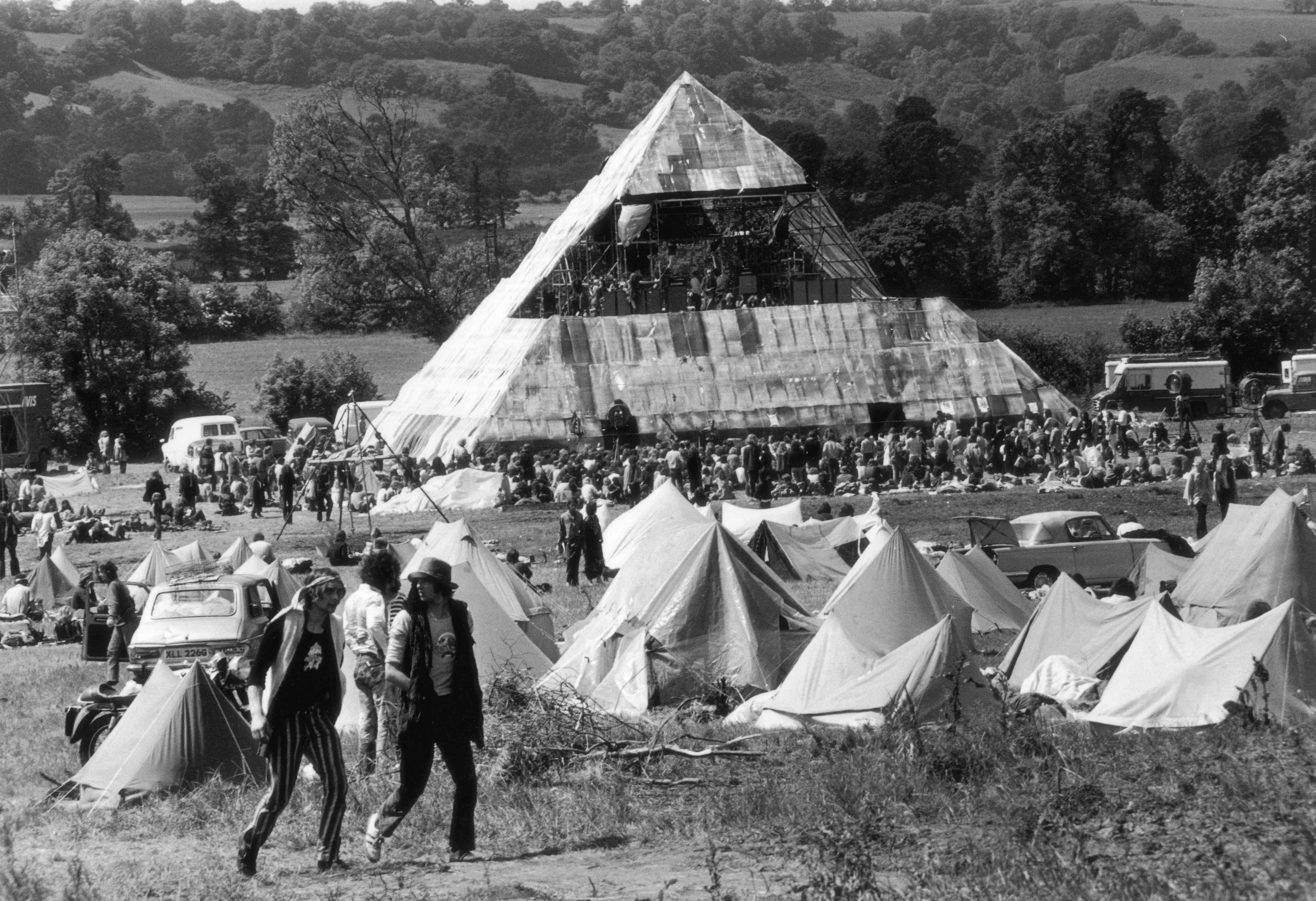

If Glastonbury’s second year of operation is remembered now for David Bowie’s first appearance there, the rest of the bill was a reminder that it had started the year before as a folk festival . The lineup featured Joan Baez, Fairport Convention and Melanie. Alongside were some very 1971 names, the likes of Hawkwind and Quintessence.

But in music 1971 should perhaps really be remembered as the year of the women. Two female luminaries gave us their most seminal albums. Carole King’s Tapestry quite simply changed the music industry, showing the record companies that it was no longer mainly males, and no longer mainly teenagers, who bought records. Tapestry, with its beautifully tuneful but reflective songs about growing into mature womanhood with its joys and disappointments sold massively among a new, adult, female market recognising their own lived experience in the lyrics. Alongside that was Joni Mitchell’s Blue, a staple on best album lists from that year on, showcasing a wondrous talent at her sublime best, music, lyrics, arrangements all demonstrating a maturity and, again, a recognition for the listener in its wistfulness, heartaches and passion.

Music was changing, a change perhaps personified by the first broadcast on BBC Two of The Old Grey Whistle Test, a calm, reflective and scholarly examination of music, very different from the adulatory frenzy of Top of the Pops.

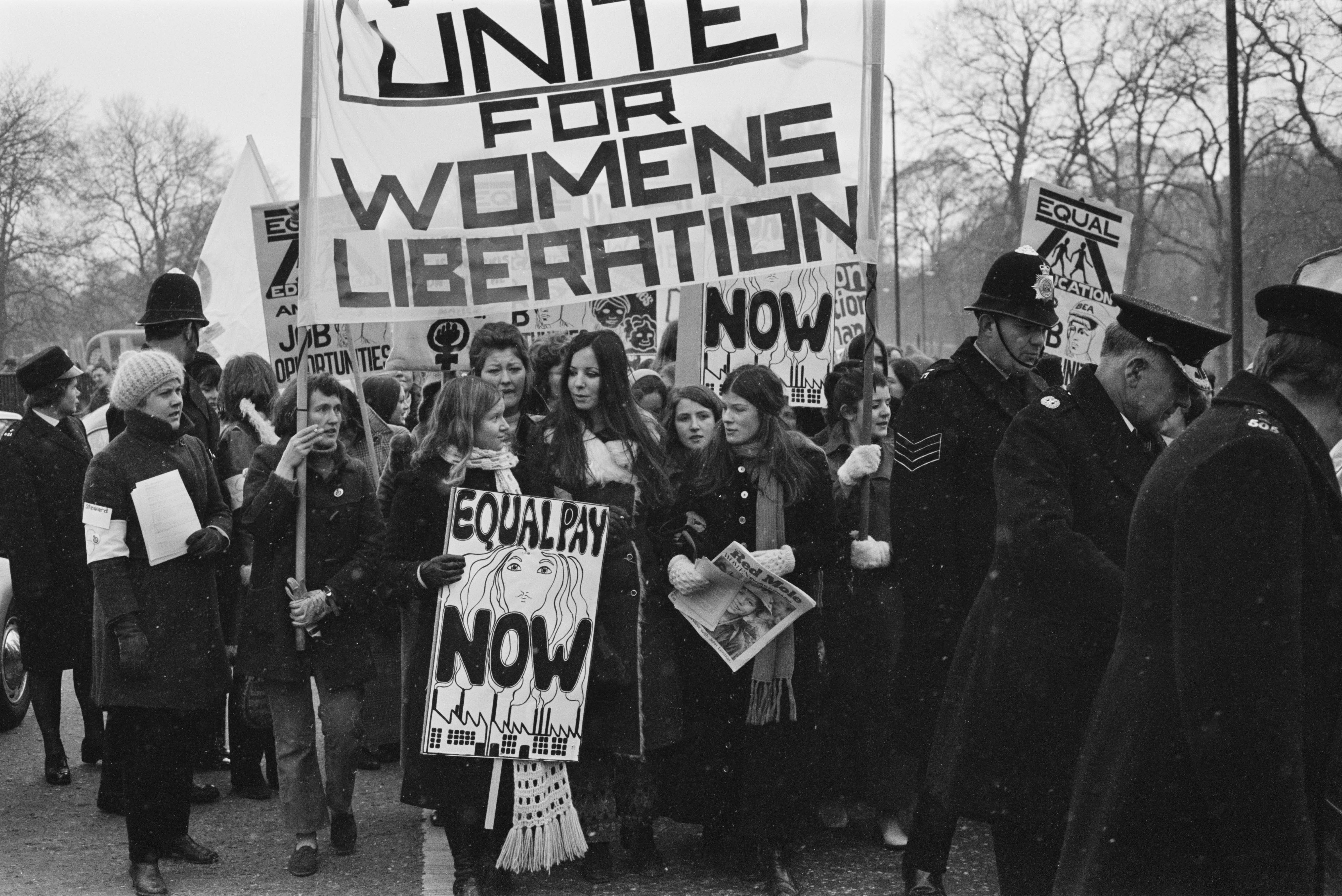

The burgeoning movement of feminism to a large degree began in ’71. It was less often called feminism, and more often what feels now like a very dated name: women’s lib. The first march by the Women’s Liberation Movement took place in London in the sleet and snow on 6 March 1971. The marchers held banners demanding everything from equal education, wages and job opportunities to free contraception and 24-hour state-funded nurseries. The demo included music, street theatre, singing and dancing.

And perhaps equally significant for feminism in that year, the Family Planning Association told its clinics to make the pill available to single as well as married women. And Erin Pizzey founded the world’s first domestic violence shelter in Chiswick, London.

Back in music, John Lennon gave us the album Imagine, the title track an anthem of hope right up to the present, while on side two (there were sides in those days) "How Do You Sleep?" his attempted demolition of Paul McCartney, remains the most vitriolic message in song from one ex-band member to another. Oasis, eat your hearts out.

Meanwhile another of his ex-bandmates, George Harrison, started what was to become a staple of the music scene: the rock concert as charity fundraiser. Live Aid had its origins in an event at New York’s Madison Square Garden on 1 August. “Do your homework,” Harrison urged Bob Geldof in 1985, when Geldof asked him for advice, because he hadn’t totally done his. Most of the money raised by the two benefit gigs was held in a US IRS account for years over a tax dispute. Nevertheless around $45m did make its way to help refugees from the genocide in Bangladesh, a country many hadn’t even heard of before the two concerts on 1 August 1971 and the subsequent album and film.

Television was changing too. Michael Parkinson did the first of his chat shows in this year. And ITV introduced Upstairs Downstairs, a class-based costume drama to which Downton Abbey can clearly trace its genesis.

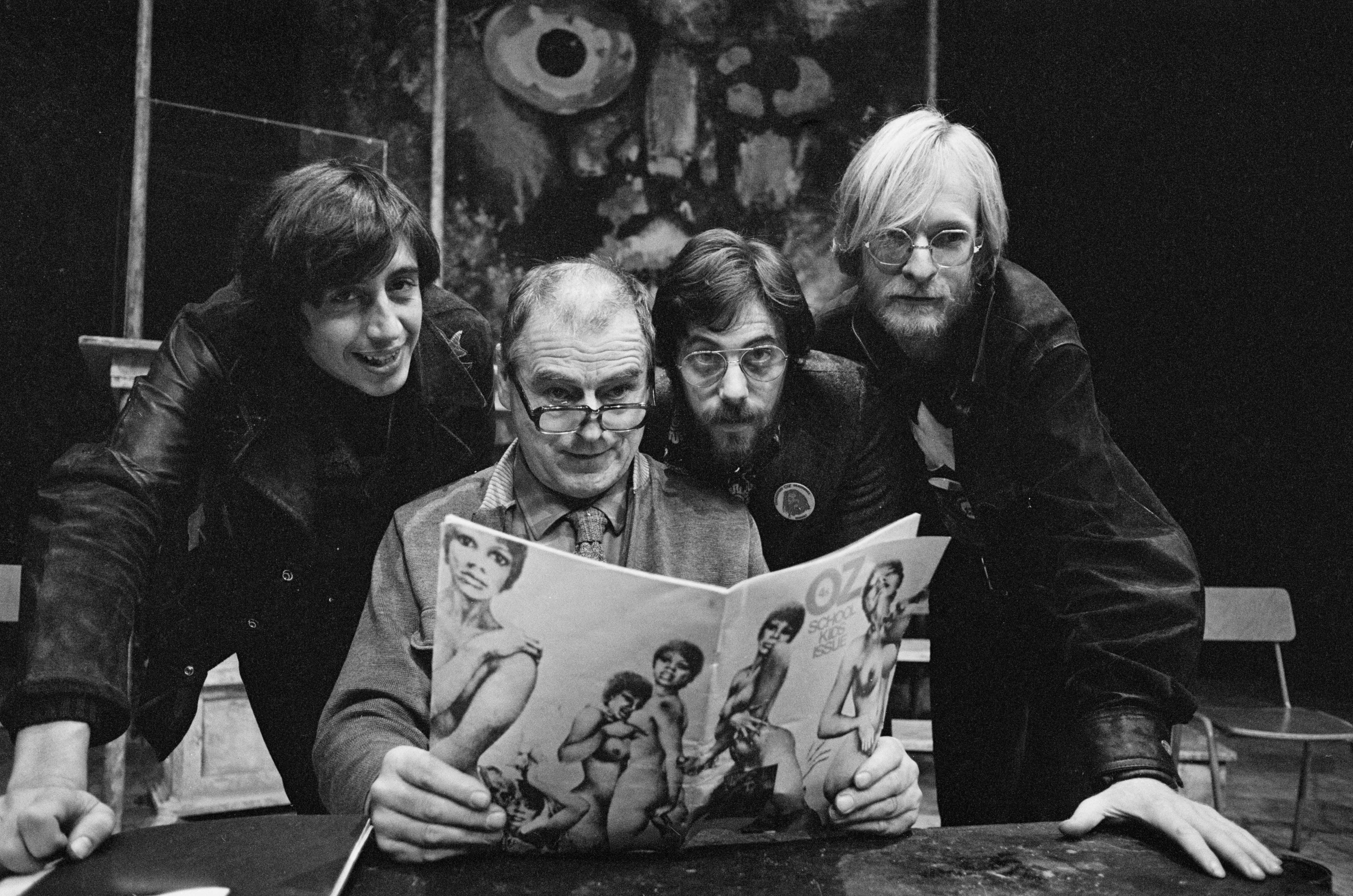

TV stayed largely "clean". The underground press didn’t. The Oz trial took place at the Old Bailey in London. The magazine’s "schoolkids’ issue" featured highly sexualised material including the pasting of the head of Rupert Bear onto the lead character of an X-rated cartoon. Oz’s leading figures were charged with “conspiracy to corrupt public morals”, a charge which in theory carried a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. The trial divided Britain, with Oz’s editors heroes to the young and despised by the middle-aged. The defendants were represented by John Mortimer and his junior Geoffrey Robertson. In his opening statement, Mortimer said: “The case stands at the crossroads of our liberty, at the boundaries of our freedom to think and draw and write what we please.” While Mr Brian Leary, prosecuting, reminded the court that the magazine “dealt with homosexuality, lesbianism, sadism, perverted sexual practices and drug taking”.

The defendants were given short prison sentences and had their long hair forcibly cut on entering prison, which caused another outcry. One of the defendants, Felix Dennis, later to become one of Britain’s most successful publishers, was given a shorter sentence than the others as Judge Argyle considered he was “very much less intelligent” than the others.

The Oz trial was Britain’s longest obscenity trial, and marked one of the last stands on public morals of an establishment, desperate to stop the march of libertarianism.

Accusations of so-called obscenity were also made about the most controversial film of the year, A Clockwork Orange. Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ novel contained stylised and glamorised violence and rape, and while it was a movie-making tour de force, its scene of an attack on a tramp provoked copycat attacks and so much denunciation in the press that Kubrick actually withdrew the film from circulation. It wasn’t re-released until after his death decades later.

When mention is made now of the miners’ strike, one’s thoughts immediately turn to 1984-5 and the confrontation between Artur Scargill and Margaret Thatcher. But for the roots of this, look back to 1971, when the militant Joe Gormley was elected as president of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), and started in that year planning a national strike (which came into force on the turn of 1972). The confrontation between Gormley and the PM Ted Heath was to last until the end of Heath’s premiership, and was the key factor in bringing Heath down.

The confrontation should have been no surprise, for in Gormley’s first NUM presidential address after being elected in the summer of ’71, he told delegates: “We must be determined that at the first possible date we will get shot of the Tories and return a Labour government, which is committed to govern in such a way as to be seen as a socialist government.”

In Northern Ireland events took a new turn. British security forces detained hundreds of suspects and put them in Long Kesh Prison, the first example of internment without trial. Twenty people died in the ensuing riots. It was also the year that the Reverend Ian Paisley launched the Democratic Unionist Party. He was to lead it for the next 37 years.

So, the roots of so much change in our national story came in 1971. But if I am to pick the key changes of that year, they are probably not the famous albums, films and political and social confrontations. I would choose above all the first broadcasts of the Open University, an educational and indeed social lifeline for so many denied the traditional educational route.

I might also point to the little noticed trial of eight members of the Welsh Language Society for destroying English language road signs, the festering of what was to become a sizeable nationalist movement.

Deserving of a footnote somewhere is the fact that the Daily Mail, which had just absorbed Britain’s oldest tabloid paper The Daily Sketch, itself published its last broadsheet issue in May 1971 and went tabloid.

Sunday Bloody Sunday, a film much less talked about than A Clockwork Orange, was the first mainstream movie with a bisexual theme. The CAT scan, allowing a doctor to see inside a body without cutting, was used for the first time. And in October the House of Commons voted in favour of joining the European Economic Community by 356 votes to 244.

Little did they realise that that would still very much be a live issue 50 years later.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments