The cost of childcare is crippling families during lockdown

Childcare was expensive enough before the pandemic, writes David Barnett. Now, some parents are having to make life-changing decisions in order to pay for childcare they aren’t even receiving

The coronavirus pandemic has brought unprecedented change, but a lot of families seem to be having a very Instagrammable time of it. Morning workouts with Joe Wicks, bedtime stories from celebrities, viral video content of children being the rays of rainbow-infused sunshine we all need in these difficult times. However, that’s not necessarily the whole story, or even part of it, for many families – especially those with younger children, or with parents who are not just seeing out the lockdown with crafting and cooking.

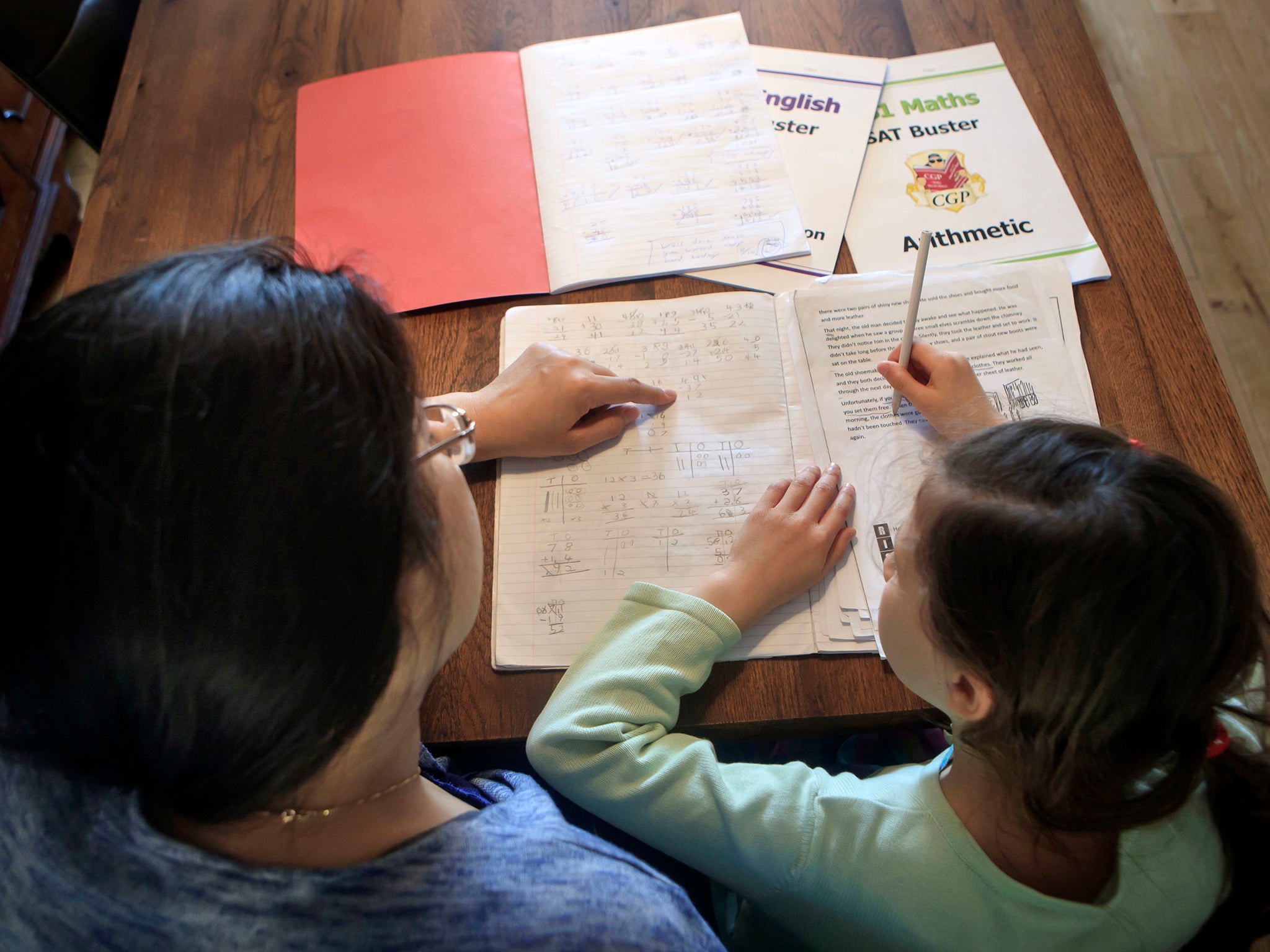

A huge number of parents are finding themselves both working from home and looking after their children. Which most would think was fine, apart from the fact that they’re still shelling out for childcare that they’re not getting. Take Dina Almuli. She is a lone parent of three children – two sons, aged 11 and five, and a two-year-old daughter.

The boys would normally be in school, and she’s juggling her own job working for the British Pain Society and trying to keep on top of their home-schooling. Her daughter is normally in a local nursery for the four days a week that Dina is usually in the office. Of course, the nursery has closed down as part of the nationwide lockdown. But Dina is still being asked to pay for it.

The nursery is charging 85 per cent of its monthly fee of around £1,750, which has left many households – especially single-parent ones such as Dina’s – completely stretched. Dina, who lives in Finchley, says: “There are a lot of parents in the same boat at this nursery, and all the nurseries around are doing the same thing. A lot of parents have got together to try to campaign for the nurseries to drop their fees, but nothing has happened yet.”

The 85 per cent policy is in place for April, and is due to be reviewed at the end of the month, but there is little optimism that life will start to return to normal so quickly. It’s a scene that is being played out across the country. Last week, Layla Moran, the Liberal Democrat education spokesperson and leadership candidate, wrote to the government to lobby for something to be done about the situation.

If the nursery is closed, they are no longer paying for food, resources or materials. They will be making a profit at this time of crisis

“Families should not be pushed into unnecessary hardship by having to pay fees for nurseries that are closed,” she said, while asking education secretary Gavin Williamson to offer enough financial support to ensure childcare institutions can survive the crisis without continuing to charge full fees.

“Nurseries provide a vital leg of our welfare state – giving children the best start in life and helping parents get out to work,” she said. “But the government’s efforts have not stopped nurseries from begging parents to pay fees of more than £1,000 a month. They know that if they don’t get the money, they won’t stay afloat. Ministers should not be pitting parents and childcare providers against each other.”

Of course, many parents understand that businesses are being pushed to the edge of an abyss by the coronavirus shutdown. “Nobody wants to see any business damaged. But even if nurseries have to stay open for children of key workers, their overheads are reduced significantly and many staff might have been laid off or furloughed,” says Dina. “It feels like many places are profiting off the situation by charging full or almost full rates for childcare that is just not being delivered.”

A petition was launched on Change.org by Bristol mother-of-one Carla Turnbull, who agrees.

“While I agree that some fees do need to be charged in order to pay their staff and rent, I don’t agree that they should be charging full fees,” she says. “If the nursery is closed, then they are no longer paying for food, resources, materials, and less on utility bills. Their incomings far outweigh their outgoings. Therefore, they will be making a profit at this time of crisis.”

Many parents, though, will be reticent about speaking out for fear of losing their place at the nursery. The battle to find good nursery care is a huge headache for parents of preschool children, especially in built-up areas. Children’s names have to be put down early, and there is no guarantee of getting a place, making for an anxiety-ridden time as maternity or paternity leave comes to an end and care is needed to allow parents to return to work.

Even when you’re getting the service that you’re paying for, costs can be crippling. At the end of last year, the government released its latest Childcare and Early Years Survey of Parents, which reported a rise in the number of families finding it “difficult” or “very difficult” to meet the costs of childcare.

According to the report, in 2019, around three-quarters (76 per cent) of children in England up to the age of four had used some form of childcare during their most recent term-time week, equating to 1.9 million children. Formal childcare was used by just under two-thirds (64 per cent) of children, in line with 62 per cent in 2018. Just over a quarter (27 per cent) of parents found it difficult or very difficult to meet their childcare costs, a rise from 2018 (23 per cent), but lower than in 2011/12 when a third (33 per cent) of parents found it difficult to meet these costs.

British parents are spending an average of £858 per month on childcare compared with France, spending just £435 a year and the Netherlands at £663 a year

The report also found that 62 per cent of mothers with children up to the age of four were in work in 2019, in line with 61 per cent in 2018. Around seven in ten (69 per cent) working mothers said that having reliable childcare helped them go out to work, a rise from 63 per cent in 2018.

Unsurprisingly given the number of children of working parents in childcare, the issue was a major one at the last general election. All the major parties offered proposals to improve affordability, with the Conservatives promising an annual £250m boost for various care policies, Labour pledging to extend the weekly 30 hours of free childcare to a wider age range as well as invest in reversing cuts to children’s centres, while the Lib Dems said they would offer 35 hours of free childcare a week to all working families with children over nine months.

According to the childcare platform Yoopies, British childcare is the second most expensive in Europe. Looking at basic fees, without taking government aid schemes into account, the UK is only just behind Switzerland, with British parents spending an average of £858 per month. Taken over a year, that works out at £1,000 more than the £9,000 it costs for a year’s university tuition.

Compare that to France at £435 a year and the Netherlands at £663 a year. Switzerland is on average £100 more expensive a month than the UK. But that doesn’t take into account the many government aid schemes across Europe that substantially reduce bills. Francesca Chong, general manager of Yoopies UK, says: “There is a big difference between the average price of care on our UK site versus our other sites in France, Spain and Germany. Even after government aid deductions, parents can expect to pay more than double than that of their European counterparts.”

According to Yoopies, not only are government aid schemes less beneficial for parents in the UK than in Europe, obtaining financial aid is a lengthy and unclear process for parents in the UK as well. For some UK families, the cost of childcare exceeds the support available, meaning parents are paying more in childcare costs than they are earning. For other eligible families, navigating access to childcare benefits is such a difficulty that parents opt out or are simply unaware of potential funding available to them.

For many families it’s a battle of hearts and minds. Do you put children in childcare, or keep them at home and someone has to give up their career?

The government report in December revealed the most common reason for parents not applying to the 30-hours scheme was that they “didn’t think they were eligible”.

Countries such as France already offer integrated booking and payment systems as part of their childcare benefit schemes, allowing parents to instantly use their allowances as discounts on their childcare payments. “Parents in the UK, however, continue to have a fragmented experience when accessing childcare benefits, with multiple entry points to access aid and complex paperwork,” Chong says. “To improve perceptions of affordability there is a real need for better funding, streamlining and educating of current schemes if they are to be beneficial for the modern family.”

The coronavirus crisis is heaping extra financial pressure on parents, especially as social distancing and isolation guidance means that grandparents can’t be relied upon to take up the slack. But the childcare providers are suffering too, says the National Day Nurseries Association (NDNA).

“Childcare providers need to ensure they have enough income to keep the business running and be able to reopen with a full complement of staff once all parents can go back to work,” says Purnima Tanuku, NDNA’s chief executive.

“Nurseries are as vital now as ever to support children of key workers and vulnerable children, so we need them to be staffed and operational,” Tanaku adds. “They need to be able to pay their staff to maintain continuity when this settles down. Recruitment is already a major issue in the sector, and nurseries do not want to lose their committed, trained staff. The government financial support is welcome, but it’s only part of their income.”

Tanaku says that the NDNA is calling for more post-crisis help to keep the businesses on their feet. “Deferring VAT payments will also help the small proportion of nurseries who have to pay them short term, but in the long term we want to see them fully exempted,” she says. “We will wait to see the detail of how the schemes will be administered and hope this will be in place quickly, as we know nurseries are worried about the impact of partial or full closures.”

For parents such as Dina, though, the immediate problem is finding the cash to pay for childcare that they are not receiving. Sea changes in the way that childcare is funded or delivered are for the aftermath of coronavirus; for now, it’s simply about making enough money to pay a closed nursery and looking after the children themselves.

Dina has made the decision to take her youngest child out of nursery care, having secured a place at the preschool unit of the primary school she will attend when old enough. It’s been a tough decision, because her daughter loves the staff at the nursery. But she is still being charged for the notice period, at 85 per cent of the full fee, even though her former partner’s work has completely dried up during the lockdown.

Many other parents don’t have the option of pulling their children out. And for those with more than one child in nursery care, the fees being asked for in the most expensive and sought-after areas are eye opening. “For many families, it’s a battle of hearts and minds,” Dina says. “Do you put children in childcare, or keep them at home and someone has to give up their career? And that usually means the woman. Do you have a third child, knowing you’ll never afford to pay for childcare, even if you have a good job? Do you downsize to a smaller house just to pay for childcare? And the waiting lists to even get in the places are insane. When all this is over, something has to change.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments